Rafia Zakaria in The Dawn

IN a recent report, the Centre for Global Development made a surprising and somewhat startling observation. Looking at the data from several recent studies, they noted that even the very best international development programmes to reduce global poverty could only produce outcomes that were 40 times less successful than the income gain people in poor countries experienced when their citizens were provided greater labour mobility. In simple non-economist terms, it means that visas work faster and better to reduce global poverty by a lot than even the very best international development programmes.

The visa, then, with the promise of mobility that it holds, is one of the few single things that has the greatest capacity to eliminate global poverty than anything else in the world.

What is true, however, is not always popular, and this is certainly true of the visa solution. While this may be true, the extent of the discrepancy between the effectiveness of international aid programmes versus work visas is quite alarming. A study published in Science magazine reveals how intensive and highly targeted programmes directed at poor countries like Pakistan and Ethiopia were successful at reducing poverty even if they were far more expensive to implement and produce.

Even so, the mood of the announcement was triumphant; pricey as it may be, their study had found that international aid could work. The fact that work visas and access to labour markets work better was never mentioned.

The international aid system is a moral hierarchy, with the aid grantors at the top.

The omission is not surprising. As another study has noted, the infrastructure of aid depends on hierarchies in which Western experts imported into impoverished environments diagnose how and what poor countries must do to escape persistent poverty. Even while development lingo has evolved to include terms like ‘local involvement’ and ‘community input’, no project is complete without the messenger experts of the West arriving to impart their pearls of wisdom.

Behind all of this, there is a hierarchy at work and it always involves donor countries and their experts being at the top. This is even more visible in public presentations of development work at this or that conference; in one example, noted in the report (but recurrent everywhere), an organiser had to fight to ensure that at least one Arabic speaker be included in a panel on international development in the Middle East and the North African region.

It’s not just panels and experts that are the problem; it is also the impact of these interventions on local populations. Take, for instance, the issue of ‘capacity building’, a term of art deployed when aid is handed out in poor communities but little improvement is seen in their metrics.

At this point, ‘capacity building’ enters to save the day, that is, to introduce skills, such as financial management, entrepreneurship, etc that would hypothetically enable better results and prove the development programmes effective after all. Few of these ‘capacity-building’ programmes actually deliver the promised, improved results.

The reason is simple. Contrary to the assumption that aid grants exist solely to eliminate global poverty in the world’s most wanting populations, the international aid system is also a moral hierarchy. The aid grantors are at the top; they have the most and know the best, but in addition to all that they are also morally superior, willing to grant assistance with little expectation in return. They are the world’s altruists, whose purity of purpose lends them the authority that no others possess. They can pretend that they are doing good while expecting nothing at all in return.

When this moral aspect of international aid and aid giving in general is noted, the international aid system can be recast not as a means of actually helping the poor (because visas and labour mobility would accomplish this with far greater efficacy) but rather a means via which a moral hierarchy is created and maintained — the world’s wealthy, also the world’s noblest, inhabiting its summit, and the wanting at the bottom.

Seen against this, the purpose of development programmes may not actually be to reduce poverty or eliminate it but rather to enable the continued existence of this moral hierarchy. Per its dimensions, the world’s poor are not simply to be pitied but also morally wanting, often too lazy or devoid of initiative to figure out how to lift themselves out of their hapless circumstances. They are the ignoble, always awaiting alms from the good and noble.

Permitting some programme of labour mobility would dismantle this structure, whose moral currency permits the West to justify wars, trade restrictions and so much else that enable the maintenance of Western dominance. Research shows that an individual’s own desire to change his or her circumstances, one that aligns with the provision of work visas, is the best predictor of success in escaping poverty. Even while development professionals create metrics for this and that, measure effectiveness through complex statistical models, these basics that show a better route than the system of international aid are ignored.

Even while virtual platforms of communication enable organisation and discussion across national and continental boundaries and time zones, even as jet travel puts the world at our disposal and makes movement across borders a regularity, Western countries continue to rely on the archaic premises that borders are real, racial and religious difference are threats and the basis on which opportunities are distributed. It is not the lack of capacity or initiative among farmers in sub-Saharan Africa or shepherds in Ethiopia, then, that explain the persistence of global poverty, it is the inability of these people to travel freely to work where the jobs are.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 18 April 2018

Tuesday, 17 April 2018

The India I grew up in has gone. These rapes show a damaged, divided nation

Anuradha Roy in The Guardian

A protest march in Kolkata for Asifa Bano, an eight-year-old girl who was raped and murdered. Photograph: Piyal Adhikary/EPA

Achilling leitmotif of Nordic crime fiction is a child leaving home to play, never to return. Detectives search out trails pointing to sexual violence and murder, and by degrees it becomes clear that the crime is not isolated: it is the symptom of a damaged community. The abduction, gang-rape, and murder in India of eight-year-old Asifa Bano reveals such damage on a terrifying scale. It shows that the slow sectarian poison released into the country’s bloodstream by its Hindu nationalists has reached full toxicity.

Where government statistics say four rapes are reported across the country every hour, sexual assault is no longer news. Indian minds have been rearranged by the constant violence of their surroundings. Crimes against women, children and minority communities are normalised enough for only the most sensational to be reported. The reasons Asifa’s ordeal has shaken a nation exhausted by brutality are four. The victim was a little girl. She was picked because she was Muslim. The murder was not the act of isolated deviants but of well-organised Hindu zealots. And the men who raped her included a retired government official and two serving police officers.

Achilling leitmotif of Nordic crime fiction is a child leaving home to play, never to return. Detectives search out trails pointing to sexual violence and murder, and by degrees it becomes clear that the crime is not isolated: it is the symptom of a damaged community. The abduction, gang-rape, and murder in India of eight-year-old Asifa Bano reveals such damage on a terrifying scale. It shows that the slow sectarian poison released into the country’s bloodstream by its Hindu nationalists has reached full toxicity.

Where government statistics say four rapes are reported across the country every hour, sexual assault is no longer news. Indian minds have been rearranged by the constant violence of their surroundings. Crimes against women, children and minority communities are normalised enough for only the most sensational to be reported. The reasons Asifa’s ordeal has shaken a nation exhausted by brutality are four. The victim was a little girl. She was picked because she was Muslim. The murder was not the act of isolated deviants but of well-organised Hindu zealots. And the men who raped her included a retired government official and two serving police officers.

When the police in Jammu (the Hindu-dominated part of Kashmir) tried to arrest the guilty last week, a Hindu nationalist mob threatened not the killers but the few honest policemen and lawyers who were trying to do their jobs. The was a mob with a difference: it included government ministers, lawyers and women waving the national flag in favour of the rapists, as well as supporters of the two major Indian parties, Congress and the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) – the party of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who is in Britain this week to attend the Commonwealth heads of government meeting.

Nationalism can be benign as well as malignant: Tagore foresaw the malignant variant a century ago. “Alien government in India is a chameleon,” he wrote. “Today it comes in the guise of an Englishman … the next day, without abating a jot of its virulence, it may take the shape of our own countrymen.” Given the right political conditions, virulent nationalism creeps into every bone, every thought process. When it leads to the calculated mutilation of a child, ethnic cleansing does not appear too far distant. If the world has understood fascism better through Anne Frank, its understanding of contemporary India will remain incomplete unless it recognises the political venom that killed Asifa.

Asifa belonged to a nomadic Muslim tribe that herds its cattle 300 miles twice a year in search of pasture. In January, when the snow lies deep in their alpine meadows, these shepherds walk down to Jammu. Here they graze their animals in the little land still available to them. Asifa went one evening to bring back grazing horses, and never returned.

Recently filed police investigations conclude that eight men imprisoned her for a week, drugged her, starved her, and took turns to rape her in a Hindu shrine. It was well organised. The mastermind, who runs a Hindu fundamentalist organisation, knew Asifa’s daily routine. The hiding place was agreed, and sedatives kept at hand. Once the girl was theirs, the kidnappers phoned a friend in another city to join their party: he travelled several hours, as if on a business trip, to rape a sedated eight-year-old. The motive was to strike terror among the Muslim nomads and drive them from Rasana, a largely Hindu village. Tribal Muslims make up a negligible percentage of the local population, perhaps 8%. Even so, the Hindus there fear “demographic change”, and have been fighting to drive them out.

Absolute darkness begins imperceptibly, as gathering dusk. Reading of 1930s Vienna in Robert Seethaler’s The Tobacconist some months ago, I began to feel an uneasy sense of familiarity. At first, only a few minor problems befall Seethaler’s Jewish tobacconist. His antisemitic neighbour, a butcher, contrives through a series of petty offences to make life difficult. After each act of vandalism, the tobacconist replaces broken glass, swabs away entrails, opens his shop again. The vandalism is a feeble precursor of what is to come. Anschluss is a few months away and it requires little conjecture to know how the novel and its tobacconist end. Even as the details of Asifa’s death emerged, another crime came to light, this time from Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, also ruled by the BJP. The father of a teenage girl wanted merely to lodge a report with the police that his daughter had been raped over several days by a legislator and his brother. The father was arrested and died soon after, allegedly beaten to death in custody.

Indian court orders arrest of politician for gang-rape

Read more

The thread that binds these crimes is the sense of invincibility that a majoritarian regime has granted its personnel and supporters. Manifestations of the newfound swagger include vandalising sprees after electoral victories, and the lynching of Muslims and Dalits (the lowest in the Hindu caste hierarchy). The general idea is to create a sense of terror and uncertainty, and in this the tacit support of the state pumps up the mobs – and they rampage with greater confidence. In swathes of rural north India, violating women to signal caste, religious and masculine supremacy is only an extension of such activity. The primeval divisions within Indian society have never been sharper. The BJP’s ruthless drive to consolidate patriarchal Hinduism has pressurised women about what they can wear, families about what they can eat, and young people about who they may marry. Parties in the opposition, envying the electoral success of the BJP, tend to speak out against this culture of sectarian hatred after first sniffing which way the wind is blowing, then gauging how strongly it is blowing.

In the India where I grew up, memories of Gandhi, Tagore and Nehru were strong; the necessity of secularism was drummed into us. We knew that our politicians were largely venal, but it was still a country in which morality and humanity mattered. Now, journalists and writers who speak up against the undeclared war on Dalits, Muslims, poor people and women are trolled by cyber-mobs. – if they’re lucky. The most publicised murder last year was of a dissenting journalist shot dead outside her home in Bengaluru, in south India.

Modi, renowned as a demagogue, is coming to be even better known for what he chooses to stay silent about. Sympathy for the suffering individual, many have noticed, is not among his most distinctive traits. When the student Jyoti Singh “Nirbhaya” was raped and killed in Delhi in 2012, it took several days of massive public outrage to stir Sonia Gandhi and her ruling Congress party, from their mansions. In the aftermath of Asifa, the current prime minister, perhaps quicker off the blocks, took a mere three days after the details of the eight-year-old’s killing were released to understand how much he stands to lose by saying nothing when the whole world is watching. The times are such that even so little so late from Modi has been seen as an acknowledgement, however reluctant, that India’s constitution requires him to ensure justice and equality for all its many communities.

Nationalism can be benign as well as malignant: Tagore foresaw the malignant variant a century ago. “Alien government in India is a chameleon,” he wrote. “Today it comes in the guise of an Englishman … the next day, without abating a jot of its virulence, it may take the shape of our own countrymen.” Given the right political conditions, virulent nationalism creeps into every bone, every thought process. When it leads to the calculated mutilation of a child, ethnic cleansing does not appear too far distant. If the world has understood fascism better through Anne Frank, its understanding of contemporary India will remain incomplete unless it recognises the political venom that killed Asifa.

Asifa belonged to a nomadic Muslim tribe that herds its cattle 300 miles twice a year in search of pasture. In January, when the snow lies deep in their alpine meadows, these shepherds walk down to Jammu. Here they graze their animals in the little land still available to them. Asifa went one evening to bring back grazing horses, and never returned.

Recently filed police investigations conclude that eight men imprisoned her for a week, drugged her, starved her, and took turns to rape her in a Hindu shrine. It was well organised. The mastermind, who runs a Hindu fundamentalist organisation, knew Asifa’s daily routine. The hiding place was agreed, and sedatives kept at hand. Once the girl was theirs, the kidnappers phoned a friend in another city to join their party: he travelled several hours, as if on a business trip, to rape a sedated eight-year-old. The motive was to strike terror among the Muslim nomads and drive them from Rasana, a largely Hindu village. Tribal Muslims make up a negligible percentage of the local population, perhaps 8%. Even so, the Hindus there fear “demographic change”, and have been fighting to drive them out.

Absolute darkness begins imperceptibly, as gathering dusk. Reading of 1930s Vienna in Robert Seethaler’s The Tobacconist some months ago, I began to feel an uneasy sense of familiarity. At first, only a few minor problems befall Seethaler’s Jewish tobacconist. His antisemitic neighbour, a butcher, contrives through a series of petty offences to make life difficult. After each act of vandalism, the tobacconist replaces broken glass, swabs away entrails, opens his shop again. The vandalism is a feeble precursor of what is to come. Anschluss is a few months away and it requires little conjecture to know how the novel and its tobacconist end. Even as the details of Asifa’s death emerged, another crime came to light, this time from Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, also ruled by the BJP. The father of a teenage girl wanted merely to lodge a report with the police that his daughter had been raped over several days by a legislator and his brother. The father was arrested and died soon after, allegedly beaten to death in custody.

Indian court orders arrest of politician for gang-rape

Read more

The thread that binds these crimes is the sense of invincibility that a majoritarian regime has granted its personnel and supporters. Manifestations of the newfound swagger include vandalising sprees after electoral victories, and the lynching of Muslims and Dalits (the lowest in the Hindu caste hierarchy). The general idea is to create a sense of terror and uncertainty, and in this the tacit support of the state pumps up the mobs – and they rampage with greater confidence. In swathes of rural north India, violating women to signal caste, religious and masculine supremacy is only an extension of such activity. The primeval divisions within Indian society have never been sharper. The BJP’s ruthless drive to consolidate patriarchal Hinduism has pressurised women about what they can wear, families about what they can eat, and young people about who they may marry. Parties in the opposition, envying the electoral success of the BJP, tend to speak out against this culture of sectarian hatred after first sniffing which way the wind is blowing, then gauging how strongly it is blowing.

In the India where I grew up, memories of Gandhi, Tagore and Nehru were strong; the necessity of secularism was drummed into us. We knew that our politicians were largely venal, but it was still a country in which morality and humanity mattered. Now, journalists and writers who speak up against the undeclared war on Dalits, Muslims, poor people and women are trolled by cyber-mobs. – if they’re lucky. The most publicised murder last year was of a dissenting journalist shot dead outside her home in Bengaluru, in south India.

Modi, renowned as a demagogue, is coming to be even better known for what he chooses to stay silent about. Sympathy for the suffering individual, many have noticed, is not among his most distinctive traits. When the student Jyoti Singh “Nirbhaya” was raped and killed in Delhi in 2012, it took several days of massive public outrage to stir Sonia Gandhi and her ruling Congress party, from their mansions. In the aftermath of Asifa, the current prime minister, perhaps quicker off the blocks, took a mere three days after the details of the eight-year-old’s killing were released to understand how much he stands to lose by saying nothing when the whole world is watching. The times are such that even so little so late from Modi has been seen as an acknowledgement, however reluctant, that India’s constitution requires him to ensure justice and equality for all its many communities.

An Alternative View - The Gas Attack on Douma, Syria

Robert Fisk in The Independent

This is the story of a town called Douma, a ravaged, stinking place of smashed apartment blocks – and of an underground clinic whose images of suffering allowed three of the Western world’s most powerful nations to bomb Syria last week. There’s even a friendly doctor in a green coat who, when I track him down in the very same clinic, cheerfully tells me that the “gas” videotape which horrified the world – despite all the doubters – is perfectly genuine.

War stories, however, have a habit of growing darker. For the same 58-year old senior Syrian doctor then adds something profoundly uncomfortable: the patients, he says, were overcome not by gas but by oxygen starvation in the rubbish-filled tunnels and basements in which they lived, on a night of wind and heavy shelling that stirred up a dust storm.

As Dr Assim Rahaibani announces this extraordinary conclusion, it is worth observing that he is by his own admission not an eyewitness himself and, as he speaks good English, he refers twice to the jihadi gunmen of Jaish el-Islam [the Army of Islam] in Douma as “terrorists” – the regime’s word for their enemies, and a term used by many people across Syria. Am I hearing this right? Which version of events are we to believe?

By bad luck, too, the doctors who were on duty that night on 7 April were all in Damascus giving evidence to a chemical weapons enquiry, which will be attempting to provide a definitive answer to that question in the coming weeks.

France, meanwhile, has said it has “proof” chemical weapons were used, and US media have quoted sources saying urine and blood tests showed this too. The WHO has said its partners on the ground treated 500 patients “exhibiting signs and symptoms consistent with exposure to toxic chemicals”.

At the same time, inspectors from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) are currently blocked from coming here to the site of the alleged gas attack themselves, ostensibly because they lacked the correct UN permits.

Before we go any further, readers should be aware that this is not the only story in Douma. There are the many people I talked to amid the ruins of the town who said they had “never believed in” gas stories – which were usually put about, they claimed, by the armed Islamist groups. These particular jihadis survived under a blizzard of shellfire by living in other’s people’s homes and in vast, wide tunnels with underground roads carved through the living rock by prisoners with pick-axes on three levels beneath the town. I walked through three of them yesterday, vast corridors of living rock which still contained Russian – yes, Russian – rockets and burned-out cars.

So the story of Douma is thus not just a story of gas – or no gas, as the case may be. It’s about thousands of people who did not opt for evacuation from Douma on buses that left last week, alongside the gunmen with whom they had to live like troglodytes for months in order to survive. I walked across this town quite freely yesterday without soldier, policeman or minder to haunt my footsteps, just two Syrian friends, a camera and a notebook. I sometimes had to clamber across 20-foot-high ramparts, up and down almost sheer walls of earth. Happy to see foreigners among them, happier still that the siege is finally over, they are mostly smiling; those whose faces you can see, of course, because a surprising number of Douma’s women wear full-length black hijab.

I first drove into Douma as part of an escorted convoy of journalists. But once a boring general had announced outside a wrecked council house “I have no information” – that most helpful rubbish-dump of Arab officialdom – I just walked away. Several other reporters, mostly Syrian, did the same. Even a group of Russian journalists – all in military attire – drifted off.

It was a short walk to Dr Rahaibani. From the door of his subterranean clinic – “Point 200”, it is called, in the weird geology of this partly-underground city – is a corridor leading downhill where he showed me his lowly hospital and the few beds where a small girl was crying as nurses treated a cut above her eye.

“I was with my family in the basement of my home three hundred metres from here on the night but all the doctors know what happened. There was a lot of shelling [by government forces] and aircraft were always over Douma at night – but on this night, there was wind and huge dust clouds began to come into the basements and cellars where people lived. People began to arrive here suffering from hypoxia, oxygen loss. Then someone at the door, a “White Helmet”, shouted “Gas!”, and a panic began. People started throwing water over each other. Yes, the video was filmed here, it is genuine, but what you see are people suffering from hypoxia – not gas poisoning.”

Independent Middle East Correspondent Robert Fisk in one of the miles of tunnels hacked beneath Douma by prisoners of Syrian rebels (Yara Ismail)

How could it be that Douma refugees who had reached camps in Turkey were already describing a gas attack which no-one in Douma today seemed to recall? It did occur to me, once I was walking for more than a mile through these wretched prisoner-groined tunnels, that the citizens of Douma lived so isolated from each other for so long that “news” in our sense of the word simply had no meaning to them. Syria doesn’t cut it as Jeffersonian democracy – as I cynically like to tell my Arab colleagues – and it is indeed a ruthless dictatorship, but that couldn’t cow these people, happy to see foreigners among them, from reacting with a few words of truth. So what were they telling me?

They talked about the Islamists under whom they had lived. They talked about how the armed groups had stolen civilian homes to avoid the Syrian government and Russian bombing. The Jaish el-Islam had burned their offices before they left, but the massive buildings inside the security zones they created had almost all been sandwiched to the ground by air strikes. A Syrian colonel I came across behind one of these buildings asked if I wanted to see how deep the tunnels were. I stopped after well over a mile when he cryptically observed that “this tunnel might reach as far as Britain”. Ah yes, Ms May, I remembered, whose air strikes had been so intimately connected to this place of tunnels and dust. And gas?

This is the story of a town called Douma, a ravaged, stinking place of smashed apartment blocks – and of an underground clinic whose images of suffering allowed three of the Western world’s most powerful nations to bomb Syria last week. There’s even a friendly doctor in a green coat who, when I track him down in the very same clinic, cheerfully tells me that the “gas” videotape which horrified the world – despite all the doubters – is perfectly genuine.

War stories, however, have a habit of growing darker. For the same 58-year old senior Syrian doctor then adds something profoundly uncomfortable: the patients, he says, were overcome not by gas but by oxygen starvation in the rubbish-filled tunnels and basements in which they lived, on a night of wind and heavy shelling that stirred up a dust storm.

As Dr Assim Rahaibani announces this extraordinary conclusion, it is worth observing that he is by his own admission not an eyewitness himself and, as he speaks good English, he refers twice to the jihadi gunmen of Jaish el-Islam [the Army of Islam] in Douma as “terrorists” – the regime’s word for their enemies, and a term used by many people across Syria. Am I hearing this right? Which version of events are we to believe?

By bad luck, too, the doctors who were on duty that night on 7 April were all in Damascus giving evidence to a chemical weapons enquiry, which will be attempting to provide a definitive answer to that question in the coming weeks.

France, meanwhile, has said it has “proof” chemical weapons were used, and US media have quoted sources saying urine and blood tests showed this too. The WHO has said its partners on the ground treated 500 patients “exhibiting signs and symptoms consistent with exposure to toxic chemicals”.

At the same time, inspectors from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) are currently blocked from coming here to the site of the alleged gas attack themselves, ostensibly because they lacked the correct UN permits.

Before we go any further, readers should be aware that this is not the only story in Douma. There are the many people I talked to amid the ruins of the town who said they had “never believed in” gas stories – which were usually put about, they claimed, by the armed Islamist groups. These particular jihadis survived under a blizzard of shellfire by living in other’s people’s homes and in vast, wide tunnels with underground roads carved through the living rock by prisoners with pick-axes on three levels beneath the town. I walked through three of them yesterday, vast corridors of living rock which still contained Russian – yes, Russian – rockets and burned-out cars.

So the story of Douma is thus not just a story of gas – or no gas, as the case may be. It’s about thousands of people who did not opt for evacuation from Douma on buses that left last week, alongside the gunmen with whom they had to live like troglodytes for months in order to survive. I walked across this town quite freely yesterday without soldier, policeman or minder to haunt my footsteps, just two Syrian friends, a camera and a notebook. I sometimes had to clamber across 20-foot-high ramparts, up and down almost sheer walls of earth. Happy to see foreigners among them, happier still that the siege is finally over, they are mostly smiling; those whose faces you can see, of course, because a surprising number of Douma’s women wear full-length black hijab.

I first drove into Douma as part of an escorted convoy of journalists. But once a boring general had announced outside a wrecked council house “I have no information” – that most helpful rubbish-dump of Arab officialdom – I just walked away. Several other reporters, mostly Syrian, did the same. Even a group of Russian journalists – all in military attire – drifted off.

It was a short walk to Dr Rahaibani. From the door of his subterranean clinic – “Point 200”, it is called, in the weird geology of this partly-underground city – is a corridor leading downhill where he showed me his lowly hospital and the few beds where a small girl was crying as nurses treated a cut above her eye.

“I was with my family in the basement of my home three hundred metres from here on the night but all the doctors know what happened. There was a lot of shelling [by government forces] and aircraft were always over Douma at night – but on this night, there was wind and huge dust clouds began to come into the basements and cellars where people lived. People began to arrive here suffering from hypoxia, oxygen loss. Then someone at the door, a “White Helmet”, shouted “Gas!”, and a panic began. People started throwing water over each other. Yes, the video was filmed here, it is genuine, but what you see are people suffering from hypoxia – not gas poisoning.”

Independent Middle East Correspondent Robert Fisk in one of the miles of tunnels hacked beneath Douma by prisoners of Syrian rebels (Yara Ismail)

Oddly, after chatting to more than 20 people, I couldn’t find one who showed the slightest interest in Douma’s role in bringing about the Western air attacks. Two actually told me they didn’t know about the connection.

But it was a strange world I walked into. Two men, Hussam and Nazir Abu Aishe, said they were unaware how many people had been killed in Douma, although the latter admitted he had a cousin “executed by Jaish el-Islam [the Army of Islam] for allegedly being “close to the regime”. They shrugged when I asked about the 43 people said to have died in the infamous Douma attack.

The White Helmets – the medical first responders already legendary in the West but with some interesting corners to their own story – played a familiar role during the battles. They are partly funded by the Foreign Office and most of the local offices were staffed by Douma men. I found their wrecked offices not far from Dr Rahaibani’s clinic. A gas mask had been left outside a food container with one eye-piece pierced and a pile of dirty military camouflage uniforms lay inside one room. Planted, I asked myself? I doubt it. The place was heaped with capsules, broken medical equipment and files, bedding and mattresses.

Of course we must hear their side of the story, but it will not happen here: a woman told us that every member of the White Helmets in Douma abandoned their main headquarters and chose to take the government-organised and Russian-protected buses to the rebel province of Idlib with the armed groups when the final truce was agreed.

There were food stalls open and a patrol of Russian military policemen – a now optional extra for every Syrian ceasefire – and no-one had even bothered to storm into the forbidding Islamist prison near Martyr’s Square where victims were supposedly beheaded in the basements. The town’s complement of Syrian interior ministry civilian police – who eerily wear military clothes – are watched over by the Russians who may or may not be watched by the civilians. Again, my earnest questions about gas were met with what seemed genuine perplexity.

But it was a strange world I walked into. Two men, Hussam and Nazir Abu Aishe, said they were unaware how many people had been killed in Douma, although the latter admitted he had a cousin “executed by Jaish el-Islam [the Army of Islam] for allegedly being “close to the regime”. They shrugged when I asked about the 43 people said to have died in the infamous Douma attack.

The White Helmets – the medical first responders already legendary in the West but with some interesting corners to their own story – played a familiar role during the battles. They are partly funded by the Foreign Office and most of the local offices were staffed by Douma men. I found their wrecked offices not far from Dr Rahaibani’s clinic. A gas mask had been left outside a food container with one eye-piece pierced and a pile of dirty military camouflage uniforms lay inside one room. Planted, I asked myself? I doubt it. The place was heaped with capsules, broken medical equipment and files, bedding and mattresses.

Of course we must hear their side of the story, but it will not happen here: a woman told us that every member of the White Helmets in Douma abandoned their main headquarters and chose to take the government-organised and Russian-protected buses to the rebel province of Idlib with the armed groups when the final truce was agreed.

There were food stalls open and a patrol of Russian military policemen – a now optional extra for every Syrian ceasefire – and no-one had even bothered to storm into the forbidding Islamist prison near Martyr’s Square where victims were supposedly beheaded in the basements. The town’s complement of Syrian interior ministry civilian police – who eerily wear military clothes – are watched over by the Russians who may or may not be watched by the civilians. Again, my earnest questions about gas were met with what seemed genuine perplexity.

How could it be that Douma refugees who had reached camps in Turkey were already describing a gas attack which no-one in Douma today seemed to recall? It did occur to me, once I was walking for more than a mile through these wretched prisoner-groined tunnels, that the citizens of Douma lived so isolated from each other for so long that “news” in our sense of the word simply had no meaning to them. Syria doesn’t cut it as Jeffersonian democracy – as I cynically like to tell my Arab colleagues – and it is indeed a ruthless dictatorship, but that couldn’t cow these people, happy to see foreigners among them, from reacting with a few words of truth. So what were they telling me?

They talked about the Islamists under whom they had lived. They talked about how the armed groups had stolen civilian homes to avoid the Syrian government and Russian bombing. The Jaish el-Islam had burned their offices before they left, but the massive buildings inside the security zones they created had almost all been sandwiched to the ground by air strikes. A Syrian colonel I came across behind one of these buildings asked if I wanted to see how deep the tunnels were. I stopped after well over a mile when he cryptically observed that “this tunnel might reach as far as Britain”. Ah yes, Ms May, I remembered, whose air strikes had been so intimately connected to this place of tunnels and dust. And gas?

Sunday, 15 April 2018

The right and left have both signed up to the myth of free market

Larry Elliot in The Guardian

Occupy Wall Street movement. After the financial crisis the public lost faith in the economics profession. Photograph: KeystoneUSA-Zuma/Rex Features

You can’t buck the market. The turn to the right taken by politics from the mid-1970s onwards was summed up in one phrase coined by Margaret Thatcher in 1988.

This idea tended to be associated with liberal economists such as Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, both of whom influenced Thatcher deeply. Both thought that left to their own devices buyers and sellers would work out the price for everything, be that a loaf of bread, a wage, or an operation in the health service.

But economists and politicians who would certainly not have classified themselves as Hayekians, Friedmanites or Thatcherites also found the idea of market forces hard to resist. The new Keynesian school believed that there might be short-term impediments – or stickiness in the jargon – and that it was the job of government to deal with these market failures. But in the long term they too thought markets would return to equilibrium.

All sorts of policies flowed from this core belief: from privatisation to curbs on trade unions; from cuts in welfare to the attempt to create an internal market in the NHS. It also justified removing constraints on capital and the hands-off approach to financial regulation in the years leading up to the banking crisis of 2008. Anybody who suggested a gigantic bubble was being inflated was told that in free markets operated by perfectly rational economic agents this could not possibly happen.

Then the financial markets froze up. This was a classic emperor’s new clothes moment, when the public realised that the economics profession did not really have the foggiest idea that the biggest financial crisis in a century had been looming. Like a doctor who had said a patient was in rude health when she was actually suffering from a life-threatening disease, it had failed when it was most needed.

Just before Christmas, I wrote a column supporting the idea for some new thinking in economics. It caused quite a stir. Some economists liked it. Others hated it and rushed to their profession’s defence.

My piece said there was a need for a more plural approach to economics, with the need for a challenge to the dominant neo-classical school as a result of its egregious failure in 2008. The argument was that a bit of competition would do economics good.

If the latest edition of the magazine Prospect is anything to go by, a debate is now well under way. Howard Reed, an economist who has worked for two of the UK’s leading thinktanks, the Institute for Public Policy Research and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, says the malaise is so serious that a “deconomics” is needed that “decontaminates the discipline, deconstructs its theoretical heart, and rebuilds from first principles”.

Reed says a retooled economics would have four features. Firstly, recognition that there is no such thing as a value-free analysis of the economy. Neo-classical economics purports to be clean and pure but uses a cloak of ethical neutrality to make an an individualistic ethos the norm.

Secondly, he says too much economics is about how humans ought to behave rather than how they actually behave. Thirdly, economics needs to focus on the good life rather than on those areas most susceptible to analysis through 19th century linear mathematics. Finally, he calls for a more pluralistic approach. Economics should be learning from other disciplines rather than colonising them.

Prospect gave Diane Coyle, a Cambridge University economics professor, the right to reply to Reed’s piece and she does so with relish, calling it lamentable, a caricature and an ill-informed diatribe.

Most modern economics involves empirical testing, Coyle says, often using new sources of data. She rejects the idea that the profession is stuck in an ivory tower fiddling around with abstruse mathematics while ignoring the real world. Rather, it is “addressing questions of immediate importance and relevance to policymakers, citizens and businesses”.

Nor is it true that the discipline requires that people be rational, calculating automatons. “It very often has people interacting with each other rather than acting as atomistic individuals, despite Reed’s charge.”

Coyle accepts that macro-economics – the big picture stuff that involves looking at the economy in the round – is in a troubled state but says this is actually only a minority field.

The point that there are many economists doing interesting things in areas such as behavioural economics is a fair one, but Coyle is on shakier ground when she skates over the problems in macro-economics.

It was after all, macro-economists – the people working at the International Monetary Fund, the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England – that the public relied on to get things right a decade ago. All were blind to what was going on, and that had quite a lot to do with their “markets tend to know best” belief system.

Policy makers did not find the works of Hayek and Friedman particularly useful when a second great depression was looming. Instead, they turned, if only fleetingly, to Keynes’s general theory, which told them it would not be wise to wait for market forces to do their work.

Reed’s argument is not just that blind faith in neo-classical economics led to the crisis. Nor is it simply that the systemic failure of 2008 means there is a need for a root-and-branch rethink. It is also that mainstream economics has been serving the interests of the political right.

Some in the profession, particularly those who see themselves as progressives, appear to have trouble with this idea. That perhaps explains why they have been so rattled by even the teeniest bit of criticism.

You can’t buck the market. The turn to the right taken by politics from the mid-1970s onwards was summed up in one phrase coined by Margaret Thatcher in 1988.

This idea tended to be associated with liberal economists such as Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, both of whom influenced Thatcher deeply. Both thought that left to their own devices buyers and sellers would work out the price for everything, be that a loaf of bread, a wage, or an operation in the health service.

But economists and politicians who would certainly not have classified themselves as Hayekians, Friedmanites or Thatcherites also found the idea of market forces hard to resist. The new Keynesian school believed that there might be short-term impediments – or stickiness in the jargon – and that it was the job of government to deal with these market failures. But in the long term they too thought markets would return to equilibrium.

All sorts of policies flowed from this core belief: from privatisation to curbs on trade unions; from cuts in welfare to the attempt to create an internal market in the NHS. It also justified removing constraints on capital and the hands-off approach to financial regulation in the years leading up to the banking crisis of 2008. Anybody who suggested a gigantic bubble was being inflated was told that in free markets operated by perfectly rational economic agents this could not possibly happen.

Then the financial markets froze up. This was a classic emperor’s new clothes moment, when the public realised that the economics profession did not really have the foggiest idea that the biggest financial crisis in a century had been looming. Like a doctor who had said a patient was in rude health when she was actually suffering from a life-threatening disease, it had failed when it was most needed.

Just before Christmas, I wrote a column supporting the idea for some new thinking in economics. It caused quite a stir. Some economists liked it. Others hated it and rushed to their profession’s defence.

My piece said there was a need for a more plural approach to economics, with the need for a challenge to the dominant neo-classical school as a result of its egregious failure in 2008. The argument was that a bit of competition would do economics good.

If the latest edition of the magazine Prospect is anything to go by, a debate is now well under way. Howard Reed, an economist who has worked for two of the UK’s leading thinktanks, the Institute for Public Policy Research and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, says the malaise is so serious that a “deconomics” is needed that “decontaminates the discipline, deconstructs its theoretical heart, and rebuilds from first principles”.

Reed says a retooled economics would have four features. Firstly, recognition that there is no such thing as a value-free analysis of the economy. Neo-classical economics purports to be clean and pure but uses a cloak of ethical neutrality to make an an individualistic ethos the norm.

Secondly, he says too much economics is about how humans ought to behave rather than how they actually behave. Thirdly, economics needs to focus on the good life rather than on those areas most susceptible to analysis through 19th century linear mathematics. Finally, he calls for a more pluralistic approach. Economics should be learning from other disciplines rather than colonising them.

Prospect gave Diane Coyle, a Cambridge University economics professor, the right to reply to Reed’s piece and she does so with relish, calling it lamentable, a caricature and an ill-informed diatribe.

Most modern economics involves empirical testing, Coyle says, often using new sources of data. She rejects the idea that the profession is stuck in an ivory tower fiddling around with abstruse mathematics while ignoring the real world. Rather, it is “addressing questions of immediate importance and relevance to policymakers, citizens and businesses”.

Nor is it true that the discipline requires that people be rational, calculating automatons. “It very often has people interacting with each other rather than acting as atomistic individuals, despite Reed’s charge.”

Coyle accepts that macro-economics – the big picture stuff that involves looking at the economy in the round – is in a troubled state but says this is actually only a minority field.

The point that there are many economists doing interesting things in areas such as behavioural economics is a fair one, but Coyle is on shakier ground when she skates over the problems in macro-economics.

It was after all, macro-economists – the people working at the International Monetary Fund, the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England – that the public relied on to get things right a decade ago. All were blind to what was going on, and that had quite a lot to do with their “markets tend to know best” belief system.

Policy makers did not find the works of Hayek and Friedman particularly useful when a second great depression was looming. Instead, they turned, if only fleetingly, to Keynes’s general theory, which told them it would not be wise to wait for market forces to do their work.

Reed’s argument is not just that blind faith in neo-classical economics led to the crisis. Nor is it simply that the systemic failure of 2008 means there is a need for a root-and-branch rethink. It is also that mainstream economics has been serving the interests of the political right.

Some in the profession, particularly those who see themselves as progressives, appear to have trouble with this idea. That perhaps explains why they have been so rattled by even the teeniest bit of criticism.

'There is no such thing as past or future': physicist Carlo Rovelli on changing how we think about time

Charlotte Higgins on Carlo Rovelli's book on the elastic concept of time. Source The Guardian

What do we know about time? Language tells us that it “passes”, it moves like a great river, inexorably dragging us with it, and, in the end, washes us up on its shore while it continues, unstoppable. Time flows. It moves ever forwards. Or does it? Poets also tell us that time stumbles or creeps or slows or even, at times, seems to stop. They tell us that the past might be inescapable, immanent in objects or people or landscapes. When Juliet is waiting for Romeo, time passes sluggishly: she longs for Phaethon to take the reins of the Sun’s chariot, since he would whip up the horses and “bring in cloudy night immediately”. When we wake from a vivid dream we are dimly aware that the sense of time we have just experienced is illusory.

Carlo Rovelli is an Italian theoretical physicist who wants to make the uninitiated grasp the excitement of his field. His book Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, with its concise, sparkling essays on subjects such as black holes and quanta, has sold 1.3m copies worldwide. Now comes The Order of Time, a dizzying, poetic work in which I found myself abandoning everything I thought I knew about time – certainly the idea that it “flows”, and even that it exists at all, in any profound sense.

We meet outside the church of San Petronio in Bologna, where Rovelli studied. (“I like to say that, just like Copernicus, I was an undergraduate at Bologna and a graduate at Padua,” he jokes.) A cheery, compact fellow in his early 60s, Rovelli is in nostalgic mood. He lives in Marseille, where, since 2010, he has run the quantum gravity group at the Centre de physique théorique. Before that, he was in the US, at the University of Pittsburgh, for a decade.

Carlo Rovelli in Bologna. Photograph: Roberto Serra / Iguana Press / G/Iguana Press / Getty Images

He rarely visits Bologna, and he has been catching up with old friends. We wander towards the university area. Piazza Verdi is flocked with a lively crowd of students. There are flags and graffiti and banners, too – anti-fascist slogans, something in support of the Kurds, a sign enjoining passers-by not to forget Giulio Regeni, the Cambridge PhD student killed in Egypt in 2016.

“In my day it was barricades and police,” he says. He was a passionate student activist, back then. What did he and his pals want? “Small things! We wanted a world without boundaries, without state, without war, without religion, without family, without school, without private property.”

He was, he says now, too radical, and it was hard, trying to share possessions, trying to live without jealousy. And then there was the LSD. He took it a few times. And it turned out to be the seed of his interest in physics generally, and in the question of time specifically. “It was an extraordinarily strong experience that touched me also intellectually,” he remembers. “Among the strange phenomena was the sense of time stopping. Things were happening in my mind but the clock was not going ahead; the flow of time was not passing any more. It was a total subversion of the structure of reality. He had hallucinations of misshapen objects, of bright and dazzling colours – but also recalls thinking during the experience, actually asking himself what was going on.

“And I thought: ‘Well, it’s a chemical that is changing things in my brain. But how do I know that the usual perception is right, and this is wrong? If these two ways of perceiving are so different, what does it mean that one is the correct one?’” The way he talks about LSD is, in fact, quite similar to his description of reading Einstein as a student, on a sun-baked Calabrian beach, and looking up from his book imagining the world not as it appeared to him every day, but as the wild and undulating spacetime that the great physicist described. Reality, to quote the title of one of his books, is not what it seems.

He gave his conservative, Veronese parents a bit of a fright, he says. His father, now in his 90s, was surprised when young Carlo’s lecturers said he was actually doing all right, despite the long hair and radical politics and the occasional brush with the police. It was after the optimistic sense of student revolution in Italy came to an abrupt end with the kidnapping and murder of the former prime minister, Aldo Moro, in 1978 that Rovelli began to take physics seriously. But his route to his big academic career was circuitous and unconventional. “Nowadays everyone is worried because there is no work. When I was young, the problem was how to avoid work. I did not want to become part of the ‘productive system’,” he says.

Academia, then, seemed like a way of avoiding the world of a conventional job, and for some years he followed his curiosity without a sense of careerist ambition. He went to Trento in northern Italy to join a research group he was interested in, sleeping in his car for a few months (“I’d get a shower in the department to be decent”). He went to London, because he was interested in the work of Chris Isham, and then to the US, to be near physicists such as Abhay Ashtekar and Lee Smolin. “My first paper was horrendously late compared to what a young person would have to do now. And this was a privilege – I knew more things, there was more time.”

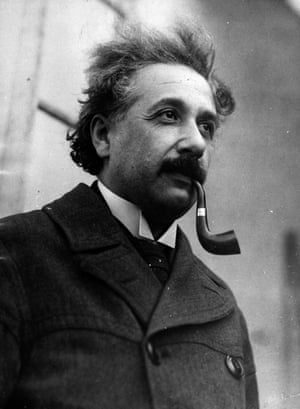

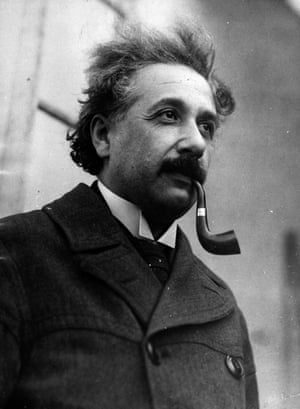

Albert Einstein worked at the Swiss patent office for seven years: ‘That worldly cloister where I hatched my most beautiful ideas.’ Photograph: Keystone/Getty Images

The popular books, too, have come relatively late, after his academic study of quantum gravity, published in 2004. If Seven Brief Lessons was a lucid primer, The Order of Timetakes things further; it deals with “what I really do in science, what I really think in depth, what is important for me”.

Rovelli’s work as a physicist, in crude terms, occupies the large space left by Einstein on the one hand, and the development of quantum theory on the other. If the theory of general relativity describes a world of curved spacetime where everything is continuous, quantum theory describes a world in which discrete quantities of energy interact. In Rovelli’s words, “quantum mechanics cannot deal with the curvature of spacetime, and general relativity cannot account for quanta”.

Both theories are successful; but their apparent incompatibility is an open problem, and one of the current tasks of theoretical physics is to attempt to construct a conceptual framework in which they both work. Rovelli’s field of loop theory, or loop quantum gravity, offers a possible answer to the problem, in which spacetime itself is understood to be granular, a fine structure woven from loops.

String theory offers another, different route towards solving the problem. When I ask him what he thinks about the possibility that his loop quantum gravity work may be wrong, he gently explains that being wrong isn’t the point; being part of the conversation is the point. And anyway, “If you ask who had the longest and most striking list of results it’s Einstein without any doubt. But if you ask who is the scientist who made most mistakes, it’s still Einstein.”

How does time fit in to his work? Time, Einstein long ago showed, is relative – time passes more slowly for an object moving faster than another object, for example. In this relative world, an absolute “now” is more or less meaningless. Time, then, is not some separate quality that impassively flows around us. Time is, in Rovelli’s words, “part of a complicated geometry woven together with the geometry of space”.

For Rovelli, there is more: according to his theorising, time itself disappears at the most fundamental level. His theories ask us to accept the notion that time is merely a function of our “blurred” human perception. We see the world only through a glass, darkly; we are watching Plato’s shadow-play in the cave. According to Rovelli, our undeniable experience of time is inextricably linked to the way heat behaves. In The Order of Time, he asks why can we know only the past, and not the future? The key, he suggests, is the one-directional flow of heat from warmer objects to colder ones. An ice cube dropped into a hot cup of coffee cools the coffee. But the process is not reversible: it is a one-way street, as demonstrated by the second law of thermodynamics.

Time is also, as we experience it, a one-way street. He explains it in relation to the concept of entropy – the measure of the disordering of things. Entropy was lower in the past. Entropy is higher in the future – there is more disorder, there are more possibilities. The pack of cards of the future is shuffled and uncertain, unlike the ordered and neatly arranged pack of cards of the past. But entropy, heat, past and future are qualities that belong not to the fundamental grammar of the world but to our superficial observation of it. “If I observe the microscopic state of things,” writes Rovelli, “then the difference between past and future vanishes … in the elementary grammar of things, there is no distinction between ‘cause’ and ‘effect’.”

To understand this properly, I can suggest only that you read Rovelli’s books, and pass swiftly over this approximation by someone who gave up school physics lessons joyfully at the first possible opportunity. However, it turns out that I am precisely Rovelli’s perfect reader, or one of them, and he looks quite delighted when I check my newly acquired understanding of the concept of entropy with him. (“You passed the exam,” he says.)

“I try to write at several levels,” he explains. “I think about the person who not only doesn’t know anything about physics but is also not interested. So I think I am talking to my grandmother, who was a housekeeper. I also think some young students of physics are reading it, and I also think some of my colleagues are reading it. So I try to talk at different levels, but I keep the person who knows nothing in my mind.”

His biggest fans are the blank slates, like me, and his colleagues at universities – he gets most criticism from people in the middle, “those who know a bit of physics”. He is also pretty down on school physics. (“Calculating the speed at which a ball drops – who cares? In another life, I’d like to write a school physics book,” he says.) And he thinks the division of the world into the “two cultures” of natural sciences and human sciences is “stupid. It’s like taking England and dividing the kids into groups, and you tell one group about music, and one group about literature, and the one who gets music is not allowed to read novels and the one who does literature is not allowed to listen to music.”

In the elementary grammar of things, there is no distinction between ‘cause’ and ‘effect’

The joy of his writing is its broad cultural compass. Historicism gives an initial hand-hold on the material. (He teaches a course on history of science, where he likes to bring science and humanities students together.) And then there’s the fact that alongside Einstein, Ludwig Boltzmann and Roger Penrose appear figures such as Proust, Dante, Beethoven, and, especially, Horace – each chapter begins with an epigraph from the Roman poet – as if to ground us in human sentiment and emotion before departing for the vertiginous world of black holes and spinfoam and clouds of probabilities.

“He has a side that is intimate, lyrical and extremely intense; and he is the great singer of the passing of time,” Rovelli says. “There’s a feeling of nostalgia – it’s not anguish, it’s not sorrow – it’s a feeling of ‘Let’s live life intensely’. A good friend of mine, Ernesto, who died quite young, gave me a little book of Horace, and I have carried it around with me all my life.”

Rovelli’s view is that there is no contradiction between a vision of the universe that makes human life seem small and irrelevant, and our everyday sorrows and joys. Or indeed between “cold science” and our inner, spiritual lives. “We are part of nature, and so joy and sorrow are aspects of nature itself – nature is much richer than just sets of atoms,” he tells me. There’s a moment in Seven Lessons when he compares physics and poetry: both try to describe the unseen. It might be added that physics, when departing from its native language of mathematical equations, relies strongly on metaphor and analogy. Rovelli has a gift for memorable comparisons. He tells us, for example, when explaining that the smooth “flow” of time is an illusion, that “The events of the world do not form an orderly queue like the English, they crowd around chaotically like the Italians.” The concept of time, he says, “has lost layers one after another, piece by piece”. We are left with “an empty windswept landscape almost devoid of all trace of temporality … a world stripped to its essence, glittering with an arid and troubling beauty”.

More than anything else I’ve ever read, Rovelli reminds me of Lucretius, the first-century BCE Roman author of the epic-length poem, On the Nature of Things. Perhaps not so odd, since Rovelli is a fan. Lucretius correctly hypothesised the existence of atoms, a theory that would remain unproven until Einstein demonstrated it in 1905, and even as late as the 1890s was being written off as absurd.

What Rovelli shares with Lucretius is not only a brilliance of language, but also a sense of humankind’s place in nature – at once a part of the fabric of the universe, and in a particular position to marvel at its great beauty. It’s a rationalist view: one that holds that by better understanding the universe, by discarding false beliefs and superstition, one might be able to enjoy a kind of serenity. Though Rovelli the man also acknowledges that the stuff of humanity is love, and fear, and desire, and passion: all made meaningful by our brief lives; our tiny span of allotted time.

What do we know about time? Language tells us that it “passes”, it moves like a great river, inexorably dragging us with it, and, in the end, washes us up on its shore while it continues, unstoppable. Time flows. It moves ever forwards. Or does it? Poets also tell us that time stumbles or creeps or slows or even, at times, seems to stop. They tell us that the past might be inescapable, immanent in objects or people or landscapes. When Juliet is waiting for Romeo, time passes sluggishly: she longs for Phaethon to take the reins of the Sun’s chariot, since he would whip up the horses and “bring in cloudy night immediately”. When we wake from a vivid dream we are dimly aware that the sense of time we have just experienced is illusory.

Carlo Rovelli is an Italian theoretical physicist who wants to make the uninitiated grasp the excitement of his field. His book Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, with its concise, sparkling essays on subjects such as black holes and quanta, has sold 1.3m copies worldwide. Now comes The Order of Time, a dizzying, poetic work in which I found myself abandoning everything I thought I knew about time – certainly the idea that it “flows”, and even that it exists at all, in any profound sense.

We meet outside the church of San Petronio in Bologna, where Rovelli studied. (“I like to say that, just like Copernicus, I was an undergraduate at Bologna and a graduate at Padua,” he jokes.) A cheery, compact fellow in his early 60s, Rovelli is in nostalgic mood. He lives in Marseille, where, since 2010, he has run the quantum gravity group at the Centre de physique théorique. Before that, he was in the US, at the University of Pittsburgh, for a decade.

Carlo Rovelli in Bologna. Photograph: Roberto Serra / Iguana Press / G/Iguana Press / Getty Images

He rarely visits Bologna, and he has been catching up with old friends. We wander towards the university area. Piazza Verdi is flocked with a lively crowd of students. There are flags and graffiti and banners, too – anti-fascist slogans, something in support of the Kurds, a sign enjoining passers-by not to forget Giulio Regeni, the Cambridge PhD student killed in Egypt in 2016.

“In my day it was barricades and police,” he says. He was a passionate student activist, back then. What did he and his pals want? “Small things! We wanted a world without boundaries, without state, without war, without religion, without family, without school, without private property.”

He was, he says now, too radical, and it was hard, trying to share possessions, trying to live without jealousy. And then there was the LSD. He took it a few times. And it turned out to be the seed of his interest in physics generally, and in the question of time specifically. “It was an extraordinarily strong experience that touched me also intellectually,” he remembers. “Among the strange phenomena was the sense of time stopping. Things were happening in my mind but the clock was not going ahead; the flow of time was not passing any more. It was a total subversion of the structure of reality. He had hallucinations of misshapen objects, of bright and dazzling colours – but also recalls thinking during the experience, actually asking himself what was going on.

“And I thought: ‘Well, it’s a chemical that is changing things in my brain. But how do I know that the usual perception is right, and this is wrong? If these two ways of perceiving are so different, what does it mean that one is the correct one?’” The way he talks about LSD is, in fact, quite similar to his description of reading Einstein as a student, on a sun-baked Calabrian beach, and looking up from his book imagining the world not as it appeared to him every day, but as the wild and undulating spacetime that the great physicist described. Reality, to quote the title of one of his books, is not what it seems.

He gave his conservative, Veronese parents a bit of a fright, he says. His father, now in his 90s, was surprised when young Carlo’s lecturers said he was actually doing all right, despite the long hair and radical politics and the occasional brush with the police. It was after the optimistic sense of student revolution in Italy came to an abrupt end with the kidnapping and murder of the former prime minister, Aldo Moro, in 1978 that Rovelli began to take physics seriously. But his route to his big academic career was circuitous and unconventional. “Nowadays everyone is worried because there is no work. When I was young, the problem was how to avoid work. I did not want to become part of the ‘productive system’,” he says.

Academia, then, seemed like a way of avoiding the world of a conventional job, and for some years he followed his curiosity without a sense of careerist ambition. He went to Trento in northern Italy to join a research group he was interested in, sleeping in his car for a few months (“I’d get a shower in the department to be decent”). He went to London, because he was interested in the work of Chris Isham, and then to the US, to be near physicists such as Abhay Ashtekar and Lee Smolin. “My first paper was horrendously late compared to what a young person would have to do now. And this was a privilege – I knew more things, there was more time.”

Albert Einstein worked at the Swiss patent office for seven years: ‘That worldly cloister where I hatched my most beautiful ideas.’ Photograph: Keystone/Getty Images

The popular books, too, have come relatively late, after his academic study of quantum gravity, published in 2004. If Seven Brief Lessons was a lucid primer, The Order of Timetakes things further; it deals with “what I really do in science, what I really think in depth, what is important for me”.

Rovelli’s work as a physicist, in crude terms, occupies the large space left by Einstein on the one hand, and the development of quantum theory on the other. If the theory of general relativity describes a world of curved spacetime where everything is continuous, quantum theory describes a world in which discrete quantities of energy interact. In Rovelli’s words, “quantum mechanics cannot deal with the curvature of spacetime, and general relativity cannot account for quanta”.

Both theories are successful; but their apparent incompatibility is an open problem, and one of the current tasks of theoretical physics is to attempt to construct a conceptual framework in which they both work. Rovelli’s field of loop theory, or loop quantum gravity, offers a possible answer to the problem, in which spacetime itself is understood to be granular, a fine structure woven from loops.

String theory offers another, different route towards solving the problem. When I ask him what he thinks about the possibility that his loop quantum gravity work may be wrong, he gently explains that being wrong isn’t the point; being part of the conversation is the point. And anyway, “If you ask who had the longest and most striking list of results it’s Einstein without any doubt. But if you ask who is the scientist who made most mistakes, it’s still Einstein.”

How does time fit in to his work? Time, Einstein long ago showed, is relative – time passes more slowly for an object moving faster than another object, for example. In this relative world, an absolute “now” is more or less meaningless. Time, then, is not some separate quality that impassively flows around us. Time is, in Rovelli’s words, “part of a complicated geometry woven together with the geometry of space”.

For Rovelli, there is more: according to his theorising, time itself disappears at the most fundamental level. His theories ask us to accept the notion that time is merely a function of our “blurred” human perception. We see the world only through a glass, darkly; we are watching Plato’s shadow-play in the cave. According to Rovelli, our undeniable experience of time is inextricably linked to the way heat behaves. In The Order of Time, he asks why can we know only the past, and not the future? The key, he suggests, is the one-directional flow of heat from warmer objects to colder ones. An ice cube dropped into a hot cup of coffee cools the coffee. But the process is not reversible: it is a one-way street, as demonstrated by the second law of thermodynamics.

Time is also, as we experience it, a one-way street. He explains it in relation to the concept of entropy – the measure of the disordering of things. Entropy was lower in the past. Entropy is higher in the future – there is more disorder, there are more possibilities. The pack of cards of the future is shuffled and uncertain, unlike the ordered and neatly arranged pack of cards of the past. But entropy, heat, past and future are qualities that belong not to the fundamental grammar of the world but to our superficial observation of it. “If I observe the microscopic state of things,” writes Rovelli, “then the difference between past and future vanishes … in the elementary grammar of things, there is no distinction between ‘cause’ and ‘effect’.”

To understand this properly, I can suggest only that you read Rovelli’s books, and pass swiftly over this approximation by someone who gave up school physics lessons joyfully at the first possible opportunity. However, it turns out that I am precisely Rovelli’s perfect reader, or one of them, and he looks quite delighted when I check my newly acquired understanding of the concept of entropy with him. (“You passed the exam,” he says.)

“I try to write at several levels,” he explains. “I think about the person who not only doesn’t know anything about physics but is also not interested. So I think I am talking to my grandmother, who was a housekeeper. I also think some young students of physics are reading it, and I also think some of my colleagues are reading it. So I try to talk at different levels, but I keep the person who knows nothing in my mind.”

His biggest fans are the blank slates, like me, and his colleagues at universities – he gets most criticism from people in the middle, “those who know a bit of physics”. He is also pretty down on school physics. (“Calculating the speed at which a ball drops – who cares? In another life, I’d like to write a school physics book,” he says.) And he thinks the division of the world into the “two cultures” of natural sciences and human sciences is “stupid. It’s like taking England and dividing the kids into groups, and you tell one group about music, and one group about literature, and the one who gets music is not allowed to read novels and the one who does literature is not allowed to listen to music.”

In the elementary grammar of things, there is no distinction between ‘cause’ and ‘effect’

The joy of his writing is its broad cultural compass. Historicism gives an initial hand-hold on the material. (He teaches a course on history of science, where he likes to bring science and humanities students together.) And then there’s the fact that alongside Einstein, Ludwig Boltzmann and Roger Penrose appear figures such as Proust, Dante, Beethoven, and, especially, Horace – each chapter begins with an epigraph from the Roman poet – as if to ground us in human sentiment and emotion before departing for the vertiginous world of black holes and spinfoam and clouds of probabilities.

“He has a side that is intimate, lyrical and extremely intense; and he is the great singer of the passing of time,” Rovelli says. “There’s a feeling of nostalgia – it’s not anguish, it’s not sorrow – it’s a feeling of ‘Let’s live life intensely’. A good friend of mine, Ernesto, who died quite young, gave me a little book of Horace, and I have carried it around with me all my life.”

Rovelli’s view is that there is no contradiction between a vision of the universe that makes human life seem small and irrelevant, and our everyday sorrows and joys. Or indeed between “cold science” and our inner, spiritual lives. “We are part of nature, and so joy and sorrow are aspects of nature itself – nature is much richer than just sets of atoms,” he tells me. There’s a moment in Seven Lessons when he compares physics and poetry: both try to describe the unseen. It might be added that physics, when departing from its native language of mathematical equations, relies strongly on metaphor and analogy. Rovelli has a gift for memorable comparisons. He tells us, for example, when explaining that the smooth “flow” of time is an illusion, that “The events of the world do not form an orderly queue like the English, they crowd around chaotically like the Italians.” The concept of time, he says, “has lost layers one after another, piece by piece”. We are left with “an empty windswept landscape almost devoid of all trace of temporality … a world stripped to its essence, glittering with an arid and troubling beauty”.

More than anything else I’ve ever read, Rovelli reminds me of Lucretius, the first-century BCE Roman author of the epic-length poem, On the Nature of Things. Perhaps not so odd, since Rovelli is a fan. Lucretius correctly hypothesised the existence of atoms, a theory that would remain unproven until Einstein demonstrated it in 1905, and even as late as the 1890s was being written off as absurd.

What Rovelli shares with Lucretius is not only a brilliance of language, but also a sense of humankind’s place in nature – at once a part of the fabric of the universe, and in a particular position to marvel at its great beauty. It’s a rationalist view: one that holds that by better understanding the universe, by discarding false beliefs and superstition, one might be able to enjoy a kind of serenity. Though Rovelli the man also acknowledges that the stuff of humanity is love, and fear, and desire, and passion: all made meaningful by our brief lives; our tiny span of allotted time.

Friday, 13 April 2018

How much is an hour worth? The war over the minimum wage

Peter C Baker in The Guardian

No idea in economics provokes more furious argument than the minimum wage. Every time a government debates whether to raise the lowest amount it is legal to pay for an hour of labour, a bitter and emotional battle is sure to follow – rife with charges of ignorance, cruelty and ideological bias. In order to understand this fight, it is necessary to understand that every minimum-wage law is about more than just money. To dictate how much a company must pay its workers is to tinker with the beating heart of the employer-employee relationship, a central component of life under capitalism. This is why the dispute over these laws and their effects – which has raged for decades – is so acrimonious: it is ultimately a clash between competing visions of politics and economics.

In the media, this debate almost always has two clearly defined sides. Those who support minimum-wage increases argue that when businesses are forced to pay a higher rate to workers on the lowest wages, those workers will earn more and have better lives as a result. Opponents of the minimum wage argue that increasing it will actually hurt low-wage workers: when labour becomes more expensive, they insist, businesses will purchase less of it. If minimum wages go up, some workers will lose their jobs, and others will lose hours in jobs they already have. Thanks to government intervention in the market, according to this argument, the workers struggling most will end up struggling even more.

This debate has flared up with new ferocity over the past year, as both sides have trained their firepower on the city of Seattle – where labour activists have won some of the most dramatic minimum-wage increases in decades, hiking the hourly pay for thousands of workers from $9.47 to $15, with future increases automatically pegged to inflation. Seattle’s $15 is the highest minimum wage in the US, and almost double the federal minimum of $7.25. This fact alone guaranteed that partisans from both sides of the great minimum-wage debate would be watching closely to see what happened.