Atul Gawande in the Guardian

Doctors are fallible; of course they are. So why do they find this so hard to admit, and how can they work more openly? Atul Gawande lifts the veil of secrecy in the first of his Reith lectures

Millions of moments like this occur every day: a human being coming to another human being with the body or mind’s troubles and looking for assistance. That is the central act of medicine – that moment when one human being turns to another human being for help.

And it has always struck me how small and limited that moment is. We have 13 different organ systems and at the latest count we’ve identified more than 60,000 ways that they can go awry. The body is scarily intricate, unfathomable, hard to read. We are these hidden beings inside this fleshy sack of skin and we’ve spent thousands of years trying to understand what’s going on inside. To me, the story of medicine is the story of how we deal with the incompleteness of our knowledge and the fallibility of our skills.

There was an essay that I read two decades ago that I think has influenced almost every bit of writing and research I’ve done ever since. It was by two philosophers – Samuel Gorovitz and Alasdair MacIntyre – and their subject was the nature of human fallibility. They wondered why human beings fail at anything that we set out to do. Why, for example, would a meteorologist fail to correctly predict where a hurricane was going to make landfall, or why might a doctor fail to figure out what was going on inside my son and fix it? They argued that there are two primary reasons why we might fail. The first is ignorance: we have only a limited understanding of all of the relevant physical laws and conditions that apply to any given problem or circumstance. The second reason, however, they called “ineptitude”, meaning that the knowledge exists but an individual or a group of individuals fail to apply that knowledge correctly.

We’ve relied on science to overcome ignorance, and the course of that work has itself been fascinating. That visit we made in 1995 to our paediatrician and everything that she did to sort out what was happening in my son could be traced back to 1628 when the English physician William Harvey, after millennia of ignorance, finally worked out that the heart is a pump that moves blood in a circular course through the body.

Another critical step came three centuries later, in 1929, when Werner Forssmann, a surgical intern in Eberswalde, Germany, made an observation. Forssmann was reading an obscure medical journal when he noticed an article depicting a horse in which researchers had threaded a long tube up its leg all the way into its heart. They described, to his amazement, taking blood samples from inside a living heart without harm. And he said: “Well, if we could do that to a horse, what if we did that to a human being?” Forssmann went to his superiors and said: “How about we take a tube and thread it into a human being’s heart?”

Their response was, in essence, “You’re crazy. You can’t do that. Whenever anyone touches the heart in surgery, it goes into fibrillation and the patient dies.”

He said: “Well what about in an animal?”

And they said: “There’s no point and you’re just an intern anyway. Who says you should even deserve to get to ask these questions? Go back to work.”

But Forssmann just had to give it a try. So he stole into the x-ray room, took a urinary catheter, made a slit in his own arm, threaded it up his vein and into his own heart and convinced a nurse to help him take a series of nine x-rays showing the tube inside his own heart.

He published the evidence – and was fired. Then in 1956, he was awarded the Nobel prize in medicine with André Cournand and Dickinson Richards who, some 20 years later at Columbia University, had taken Forssmann’s findings and recognised that you could not only put a catheter into the human heart but also shoot dye through the catheter. That enabled them to take pictures and see from the inside how the heart actually worked. Together the three had founded the field of cardiology. After this, doctors began devising ways to fix what was found going wrong inside the heart.

Science is concerned with universal truths, laws of how the body or the world behaves. Application, however, is concerned with the particularities, and the test of the science is how the universalities apply to the particularities. Do the general ideas about the worrying sounds the paediatrician heard in my son’s chest correspond with the unique particularities of Walker? Here Gorovitz and MacIntyre saw a third possible kind of failure. Besides ignorance, besides ineptitude, they said that there is necessary fallibility, some knowledge science can never deliver on. They went back to the example of how a given hurricane will behave when it makes landfall, how fast it will be going when it does, and what they said is that we’re asking science to do more than it can when we ask it to tell us what exactly is going on. All hurricanes follow predictable laws of behaviour but no hurricane is like any other hurricane. Each one is unique. We cannot have perfect knowledge of a hurricane, short of having a complete understanding of all the laws that describe natural processes and a complete description of the world, they said. It required, in other words, omniscience, and we can’t have that.

The interesting question, then, is how do we cope? It’s not that it’s impossible to predict anything. Some things are completely predictable. Gorovitz and MacIntyre gave the example of a random ice cube in a fire. An ice cube is so simple and so similar to other ice cubes that you can have complete assurance that if you put it in the fire, it will melt. Our puzzle is: are human beings more like hurricanes or more like ice cubes?

Following the paediatrician’s instructions, we took Walker to the emergency room. It was a Sunday morning. A nurse took an oxygen monitor, one of those finger probes with the red light, and put it on the finger of his right hand. And the oxygen level was 98%, virtually perfect. They took a chest x-ray, and it showed that the lungs were both whited out. They read it. They said: “This is pneumonia.” They did a spinal tap to make sure that it wasn’t signs of infection that had spread from meningitis. They started him on antibiotics and they called the paediatrician to let her know the diagnosis they’d found. It wasn’t the heart, they said. It was the lungs. He had pneumonia. And she said: “No, that can’t be right.” She came into the emergency room and she took one look at him – he was having trouble breathing, he was not doing great – and she saw that the finger probe with the oxygen monitor was on the wrong finger.

It turns out there are certain conditions in which the aorta can be interrupted. You can be born with an incomplete aorta and so the blood flow can come out of the heart and go to the right side of the upper body, into the hand that had that probe, but it may not go to the left side of the upper body or anywhere else. And that turned out to be what was going on. She switched the probe over to the left hand and he had an unreadable oxygen level. He was in fact going into kidney and liver failure. He was in serious trouble. She had caught a failure to apply the knowledge science has to this particular situation.

Then the team made a prediction. In this circumstance, we do have a drug – only put into use, it turned out, about a decade before my son was born: prostaglandin E2, a little molecule that can reopen the foetal circulation. When you’re a foetus in the womb, you have a bypass system that sends a separate blood supply that can stay open for a couple of weeks after birth. This system had shut down and that’s why he went into failure. But this molecule can reopen that pathway and the prediction was that this child was like every other child – that you could know what had happened to other children and could apply it here and that it would open up that foetal circulation, this bypass system. And it did. That gave him time to recover in the intensive care unit, to let his kidney and his liver recover, to let his gut start working again, and then to undergo cardiac surgery to replace his malformed aorta and to fix the holes that were present in his heart as well. They saved him.

They saved him.

There are more and more ways in which we are as knowable as ice cubes. We understand with great precision how mothers can die in childbirth, how certain tumours behave, how the Ebola virus spreads, how the heart can go wrong and be fixed. Certainly, we have many, many areas of continuing ignorance – how to stop Alzheimer’s disease or metastatic cancers, how we might make a vaccine against this virus we’re dealing with now. But the story of our time, I think, is as much a story about struggling with ineptitude as struggling with ignorance.

You go back a hundred years or more, and we lived in a world where our futures were governed largely by ignorance. But over this last century, we’ve come through an extraordinary explosion of discovery. The puzzle has, therefore, become not only how we close the gaps of ignorance open to us, but also how we ensure that the knowledge gets through, that the finger probe is on the correct finger.

Next to my son, in the intensive care unit, there was a child from Maine, which is about 200 miles away, who had virtually the same diagnosis that Walker had. And when this boy was diagnosed, it took too long for the problem to be recognised, for transportation to be arranged, and for him to get that drug to give him back that open circulation. The result was that the poor child with the same condition my son had, in the very next bed to ours, gone into complete liver and kidney failure, and his only chance was to wait for an organ transplant and hope for a future that was going to be very different from the one my son was going to have.

And then I think back on my family. My parents come from India; my father from a rural village, my mother from a big city in the north. If Walker had been anything like my nieces and nephews in the village where my family still farms – they’re farmers growing wheat and sugarcane and cotton – and if he’d been there, there would have been no chance at all.

There’s a misconception about global health. We think global health is about care in just the poorest parts of the world. But the way I think about global health, it’s about making care better everywhere – the idea that we are trying to deploy the capabilities that we have discovered over the last century, town by town, to every person alive. We’ve had an extraordinary transformation around the world. Economically, even with the last recession, we’ve had the rising of global economies on every continent and the result has been a dramatic change in the length of lives all across the world. Respiratory illness and malnutrition used to be the biggest killers. Now it’s cardiovascular disease; road traffic accidents are a top five killer and cancers are in the top 10. With economic progress has come the broader knowledge for people that solutions exist.

My family members in our village in India know that solutions exist to the problems they have, and so the puzzle is how we deploy that capability everywhere – in India, in Maine, across the UK, Europe, Latin America, the world. We’re only just discovering the patterns of how we begin to do that.

In the course of this year’s Reith lectures, I’m going to attempt to unpack three ideas. First is what we’re learning from opening the door, from seeing behind the curtains of how medicine and public health are actually practised and discovering how much can be done better that saves lives and reduces suffering. Second is the reality of our necessary fallibility and how we cope effectively with the fact that our knowledge is always limited. Third, I will consider the implications of both of these – the implications of what we’re learning about our ineptitude and about our necessary fallibility – for the global future of medicine and health.

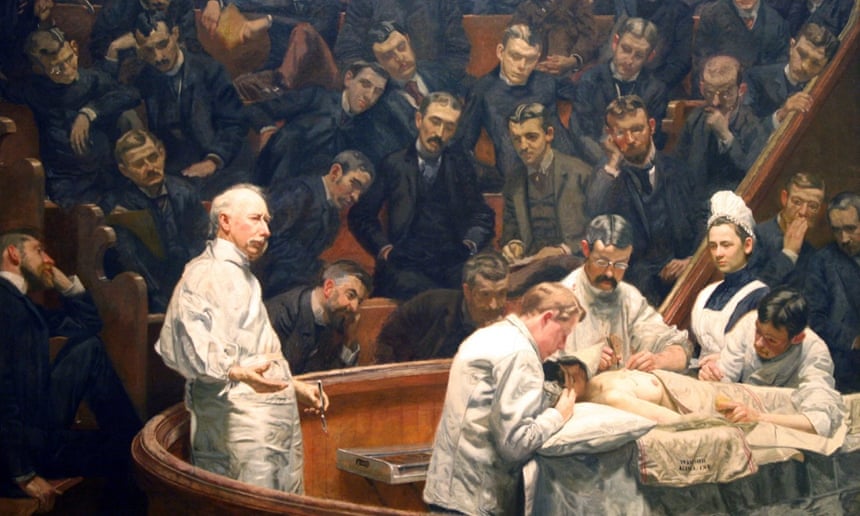

It is uncomfortable looking inside our fallibility. We have a fear of looking. We’re like the doctors who dug up bodies in the 19th century to dissect them, in order to know what was really happening inside. We’re looking inside our systems and how they really work. And like before, what we find is messier than we knew and sometimes messier than we might have wanted to know.

In some ways, turning on the cameras inside our world can be more treacherous. There’s a reason that Gorovitz and MacIntyre labelled the kind of failures we have “ineptitude”. There’s a sense that there’s some shame or guilt attached to the fact that we don’t get it right all the time. And exposing this reality can make people more angry than exposing the reality of how the body works. Therefore, we’ve blocked many of these efforts to try to provide some transparency to what’s going on. Audiotapes are often not allowed, the video recorders are turned off. We have no black box for what happens in our operating rooms or in our clinics. The data, when we have it, is often locked up. You can’t know, even though we have the information, which hospitals have a better complication rate in certain kinds of operations than others. There’s a fear of misuse, a fear of injustice in doing it, in exposing it.

Arguably, not opening up the doors puts lives at stake. What we find out can often be miraculous. By closing ourselves off, we’re missing important opportunities.

The doctors told us when Walker went home that he was going to need a second operation. The repair that he’d had was one that replaced a section of his aorta – the tube coming out of his heart to carry blood supply throughout the rest of the body – with an artificial tube when he was 11 days old. It was almost like a straw. Now they had designed it to expand a bit as he grew, but it was not going to accommodate an adult-sized body. So they told us that when he became a teenager he would have to get a new replacement aorta and that he would have to undergo a major operation. Being a surgery resident, I knew what that entailed. Repeat aortic surgery has up to a 5% chance of death and a 25% chance of paralysis. We lived in some fear about when that moment would come.

When that moment came, he was 14 years old, and the world had changed. By then technology had developed to allow his aorta to be expanded with a simple catheter. We found the expert who had learned, and even devised, some of the methods for being able to do that, in Boston. He explained to me, cardiologist to surgeon, just how it’s done and sometimes you learn stuff you don’t necessarily want to know. He talked about how he would have to apply pressure to a balloon that would be threaded up inside the aorta. I asked how he knew what pressure to apply. He said it was by feel. He could feel the vessel tearing, and the trick was to tear it just enough that it can expand but not so much that it ruptures.

There was a necessary fallibility in what he was attempting to do – some irreducible probability of failure. But Walker got through that procedure just fine. The extraordinary thing was the very next day he went home, and the day after that he was so well that he played sports and injured his ankle on the playing field. This June he graduated from high school and this autumn he started college. He’s going to live a long and normal life, and that is amazing. The key question we have to ask ourselves is how are we going to make it possible for others to have that, how do we fulfil our duty to make it possible for others? The only way I can see is by removing the veil around what happens in that procedure room, in that clinic, in that office or that hospital. Only by making what has been invisible visible. This is why I write, this is why we do the science we do – because this is how we understand – and that is the key to the future of medicine.