Warne and Murali's big turn has given way to something more subtle.

Jon Hotten in Cricinfo

The life of the impoverished writer has an occasional upside, and one of those came along a couple of weeks ago at the Guildford Book Festival, where I did an event with Tom Collomosse, cricket correspondent for the Evening Standard and Mark Nicholas, the former Hampshire captain turned commentator. Nicholas told a story about facing Derek Underwood on an uncovered pitch. It was early in his career, which began at Hampshire in 1978. They were playing Kent in a three-day game and when the rain came down, the captains got together and negotiated a deal: Hampshire would chase 160 on the last afternoon to win.

----Also read

----

Paul Terry and Gordon Greenidge went in. Greenidge took six from the first over. Underwood opened at the other end and Terry got through it by playing from as deep in his crease as he could get. Greenidge took another six runs from the next at his end. Underwood came in again, having had six deliveries to work out the pitch. By the time Nicholas had been in and out shortly afterwards, Hampshire were 12 for 4.

"Derek didn't really bowl spin on wet pitches," he explained. "What he did was hold it down the seam and cut the ball. When you were at the non-striker's end, you could hear it" - he made a whirring sound - "it was an amazing thing."

Nicholas described the nearly impossible task of trying to bat against a ball that reared up from almost medium pace with fielders surrounding you and the immaculate Alan Knott breathing down your neck from behind the stumps. Hampshire lost, of course.

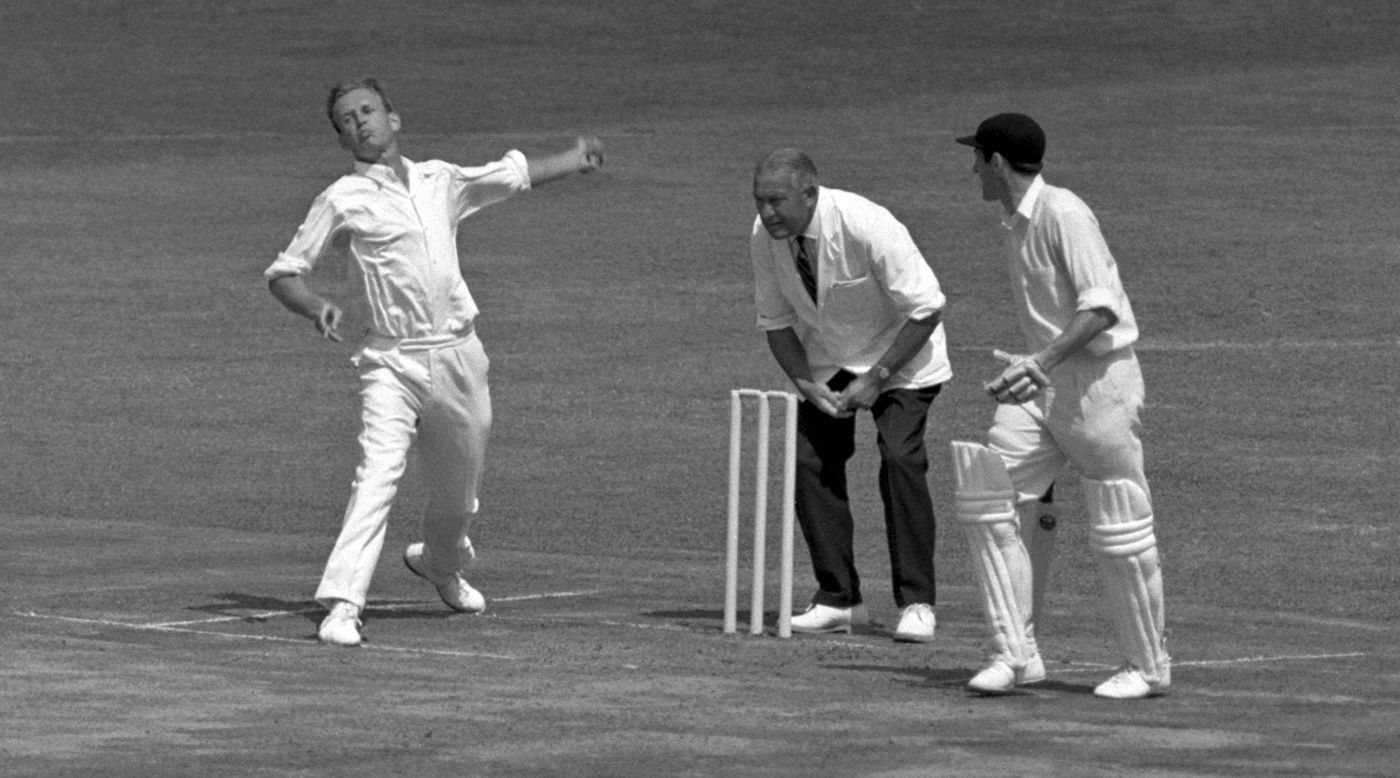

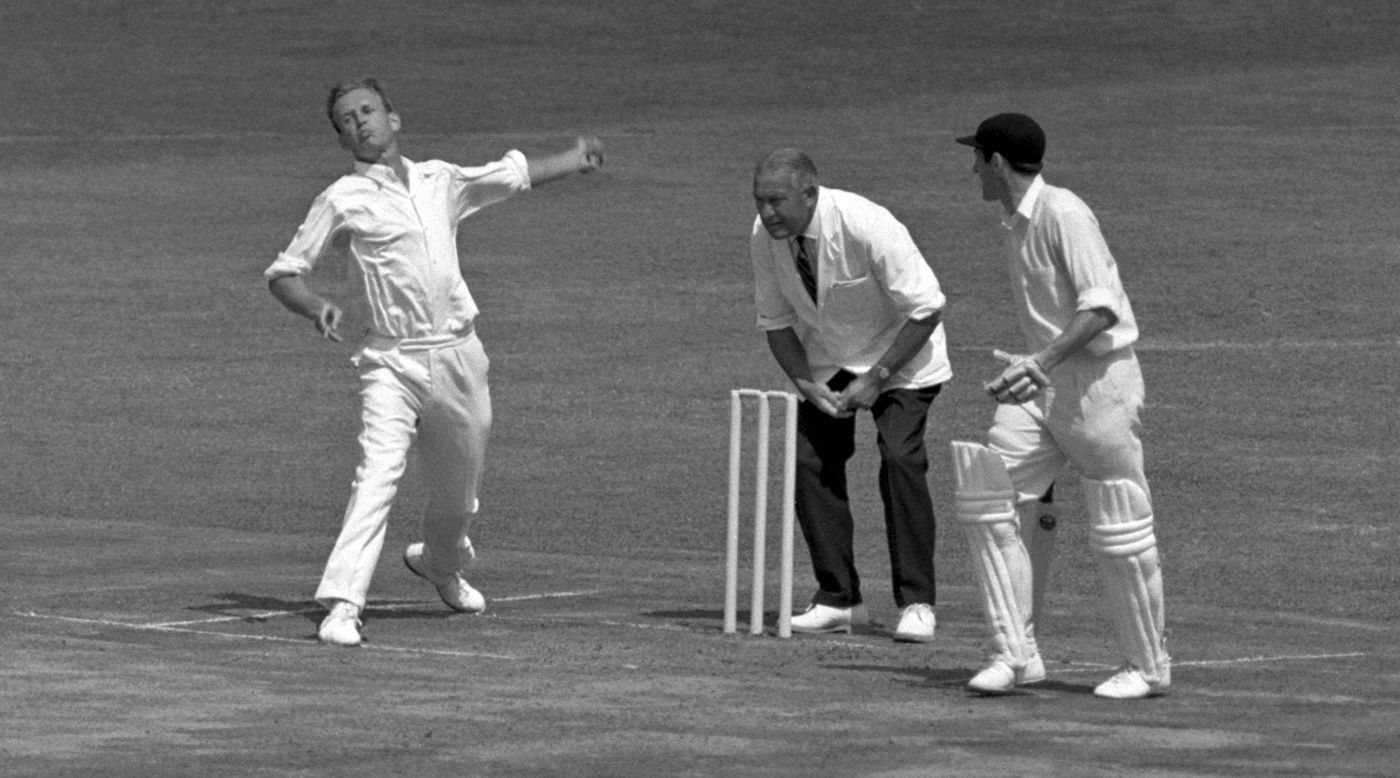

"Deadly" Derek and uncovered pitches are a part of history now, but those who can recall his flat-footed, curving run and liquid movement through the crease saw a bowler who was much more than just a specialist on drying wickets. Whatever the weather, whatever the day, he had the ball for it: 2465 first-class wickets at 20.28 tell his story.

Underwood had a thousand of those wickets by the age of 25 and retired in 1987 at 42. The game, and spin bowling, have changed irrevocably since, yet the spooky art is still shining, and perhaps about to enter a new golden age.

R Ashwin stands at the top of the Test bowling rankings, New Zealand the latest to fall to his strange magic. His buddy Ravindra Jadeja knocks them down at the other end. Bangladesh unleashed the 18-year-old Mehedi Hasan on England, and he had a five-bag on day one. Even England - brace yourselves for this - played three spinners in that game, and may well do so throughout the first part of the winter. Far from killing spin bowling, as it was supposed to do, the new way of batting has encouraged a new style of response.

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA Photos

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA Photos

To chart an evolution is fascinating. It is not so long since Shane Warne and Muttiah Muralitharan and Anil Kumble slipped from the game, Warne having reasserted legspin, Murali reinventing offspin. The future looked as though it may be big; huge freaky turn of the kind that pair specialised in. Instead, it has become something more subtle: the notion of beating the bat narrowly on both edges.

These are broad brush strokes of course, and evolution doesn't come in a straight line. It's deeply intriguing though that T20 cricket has played such a role. Through Ashwin, who emerged there, and Jadeja and Sunil Narine and others, it raised the value of cleverness, of invention. Big bats were sometimes defeated by small or no turn. The slow ball was harder to hit. As the techniques bled into Test cricket, where wickets deteriorate and change and the psychology of batting switches, they have grown in value.

We're undoubtedly living through an era in which batting has been revolutionised, undergoing its greatest change in a century. It's the nature of the game that bowling should come up with an answer, and maybe we're starting to see its first iterations. As Jarrod Kimber pointed out in his piece about the inquest into the death of Phillip Hughes, there are more very fast bowlers around now than for generations. Spin bowling is making its move too. And just as the small increments in speed increase in value the higher they go - ask any batsman about the difference between 87mph and 90mph, and then 90mph and 93 or 94mph - the small changes that, for example, Ashwin is producing have their dividend too.

Underwood once described bowling, tongue no doubt in cheek, as, "a low-mentality occupation". His variation was as simple as an arm ball, and yet in the pre-DRS age, it brought him many lbw decisions. Now the subtle changes in the spooky art are wrecking a new and welcome kind of havoc of which Deadly will surely approve. Should we call it the era of small spin?

by Girish Menon

Modern science is founded on the belief in the Genesis, that nature was created by a law-giving God and so we must be governed by "laws of nature".

Equally important was the belief that human beings are made in the image of God and, as a consequence, can understand these "laws of nature".

What do scientists have to say to that?

I say all scientists are therefore Judeo-Christian in their beliefs.

James Moore in The Independent

Those Brexiteers who fondly believe that Britain will be able to have its cake and eat it too as regards trade with the EU often used to like to point to Canada as a potential model for our future relationship with our former partners.

Canada, you see, was in the process of negotiating a trade deal that would have eliminated nearly all the tariffs between the two sides.

It would have thus facilitated access to the European single market for the country without it being a member and having to accept lots of Europeans turning up and looking for work in Toronto.

Everything was going swimmingly until, that is, the Walloons of Belgium kicked up a fuss and threatened to derail the deal, the future of which is now hanging on a knife edge.

To get agreements like the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (Ceta) up and running requires the assent of all of the EU’s 28 member states. Unfortunately, before Belgium can add its name to the list it first has to secure the assent of six regional assemblies. The Wallonian one is worried about the impact of the deal on its farmers.

Cue a blizzard of statements, and counter statements, and threats and counter threats, as both sides face up to the fact that they may have wasted seven years of complex and painstaking work.

Critics of the EU in Britain have used the debacle to bolster the case for leaving.

But critics within the EU have tabled a rather different argument. They suggest that the problem lies with Brussels having ceded too much control over trade to national Parliaments. There is a rich irony in the fact that Britain and its Eurosceptics are part of the reason for that.

For years they preached the virtue of national vetoes and subsidiarity. No handing power to Brussels Bureaucrats!

That may now come back to bite them because it might just scupper hopes of securing a favourable trade deal with Europe.

But, but, but we buy lots from the Wallonian farmers so they won’t have a problem with us!

That was the knuckle-headed response of Brexit supporting minister Chris Grayling. We’ve heard many variants on that sort of theme in recent months.

It’s true that Grayling’s flimsy argument was given something of a boost when the entirely more substantial figure of Germany’s Angela Merkel said she didn’t necessarily see parallels between this debacle and the upcoming talks between the UK and the EU.

But what if someone does kick up a fuss when the outcome of those talks becomes known? Germany might not, despite the childish insults lobbed its way by some right wing politicians and some right wing newspapers. Germany, however, doesn’t speak for the entire EU.

Perhaps the Spanish will decide to throw a spanner into the works unless there’s some movement on the question of Gibraltar. You could hardly blame the Poles for digging their heels in given the way Britain has treated the citizens of that country who live here. Maybe the French will decide it’s time for some payback for past British obstructionism.

Hang on, I hear you say, they’re grown ups. They surely wouldn’t stoop to such tactics. They’ll want a deal that works for both sides too.

Perhaps that’s so. But would you really be confident in ruling out the risk of a repeat performance when it’s Britain’s turn?

The Canadians will manage without this deal. They’re already part of the North American Free Trade Agreement, and they have trade deals in place with other countries besides.

Britain shorn of the EU has nothing of the sort. And it has a very different international image to the one that Canada has.

You couldn’t imagine its Prime Minister Justin Trudeau not guaranteeing the rights of Europeans living in his country if the issue cropped up, or of tolerating calls for child refugees to submit to dental testing.

Goodwill and good PR are powerful currencies, and Trudeau has lots of both, in stark contrast to Theresa May’s nasty and inward looking Tory administration.

An administration that doesn’t appear to have anything resembling a strategy beyond waving its fists, stomping its feet and threatening to go home and sulk if its former European friends won’t play the game by its rules.

Soon the reality of that will start to bite. The sort of problems Canada is having with Europe may ultimately pale by comparison to the ones faced by Britain.

We’ll know who to blame when they emerge. Clue: it won’t be the Wallonian farmers or their surrogates.

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA Photos

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA Photos