Outside was panic. Barely a couple of hours after Donald Trump had been declared the next president of the United States and even the political columnists, those sleek interlocutors of power, were in shock. At the National Gallery in London, however, one of the few thinkers to have anticipated Trump’s rise was ready to see some paintings. Over from Germany for a few days of lectures, Wolfgang Streeck had an afternoon spare – and we both wanted to see the Beyond Caravaggio exhibition.

Nothing in his work prepares you for meeting Streeck (pronounced Stray-k). Professionally, he is the political economist barking last orders for our way of life, and warning of the “dark ages” ahead. His books bear bluntly fin-de-siecle titles: two years ago was Buying Time, while the latest is called How Will Capitalism End?(spoiler: not well). Even his admirers talk of his “despair”, by which they mean sentences such as this: “Before capitalism will go to hell, it will for the foreseeable future hang in limbo, dead or about to die from an overdose of itself but still very much around, as nobody will have the power to move its decaying body out of the way.”

What does such gloom look like in the flesh? Small glasses, neat side parting and moustache, a backpack, a smart anorak and at least a decade younger than his 70 years. Alluding to Trump’s victory, he cheerily declares “What a morning!” as if discussing the likelihood of rain, then strolls into the gallery.

Nothing in his work prepares you for meeting Streeck (pronounced Stray-k). Professionally, he is the political economist barking last orders for our way of life, and warning of the “dark ages” ahead. His books bear bluntly fin-de-siecle titles: two years ago was Buying Time, while the latest is called How Will Capitalism End?(spoiler: not well). Even his admirers talk of his “despair”, by which they mean sentences such as this: “Before capitalism will go to hell, it will for the foreseeable future hang in limbo, dead or about to die from an overdose of itself but still very much around, as nobody will have the power to move its decaying body out of the way.”

What does such gloom look like in the flesh? Small glasses, neat side parting and moustache, a backpack, a smart anorak and at least a decade younger than his 70 years. Alluding to Trump’s victory, he cheerily declares “What a morning!” as if discussing the likelihood of rain, then strolls into the gallery.

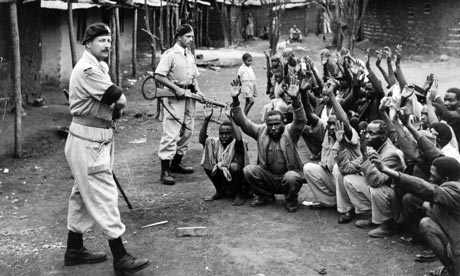

Decadence… Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard. Photograph: The National Gallery London

You don’t merely look at a Caravaggio; you square up to one. The scenes are tightly cropped, with characters that jostle and stare at the viewer. Their mordancy is a tonic to Streeck, who laughs with delight. He pauses in front of Boy Bitten by a Lizard and admires how the lizard clings on with its teeth to the boy’s finger. At a scene of cardsharps he exclaims, “Feel the decadence! The threat of violence!”

He notes how many paintings date from just before the thirty years’ war: “They’re full of the anticipation that the world is about to fall apart.”

Then comes The Taking of Christ, a dark, dense painting that shows Jesus just after his betrayal by Judas. Gripped by his treacherous former disciple, Christ looks down, ready to be bundled off by the armoured Roman centurions. “Caravaggio is always there just before the explosion,” Streeck observes. “This morning might have been a Caravaggio moment: just before the election of Trump.”

Like Caravaggio before the explosion, Streeck has been hanging around this crash scene for years – long before the plane came hurtling down and the centrist politicians and pundits began rushing around.

At a time when macroeconomists have failed and other academics have retreated into disciplinary solipsism, Streeck is one of the few (other exceptions include Mark Blyth, Colin Crouch and the Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change) to have risen to the moment. Many of the themes that will define this year, this decade, are in his work. The breakup of Europe, the rise of plutocrat-populists such as Trump, the failures of Mark Carney and the technocratic elite: he has anatomised all of them.

Why should oligarchs be interested in their countries’ democratic stability if, apparently, they can be rich without it?

This summer, Britons mutinied against their government, their experts and the EU – and consigned themselves to a poorer, angrier future. Such frenzies of collective self-harm were explained by Streeck in the 2012 lectures later collected in Buying Time:

Professionalised political science tends to underestimate the impact of moral outrage. With its penchant for studied indifference … [it] has nothing but elitist contempt for what it calls “populism”, sharing this with the power elites to which it would like to be close … [But] citizens too can “panic” and react “irrationally”, just like financial investors … even though they have no banknotes as arguments but only words and (who knows?) paving stones.

Here he is in 2013, foreshadowing the world of LuxLeaks, SwissLeaks and the Panama Papers and their revelations of a one-sided class war – by the 1% against the rest of us:

Why should the new oligarchs be interested in their countries’ future productive capacities and present democratic stability if, apparently, they can be rich without it, processing back and forth the synthetic money produced for them at no cost by a central bank for which the sky is the limit, at each stage diverting from it hefty fees and unprecedented salaries, bonuses, and profits as long as it is forthcoming – and then leave their country to its remaining devices and withdraw to some privately owned island?

And in a 2015 essay, he warns that resentment against such elites will not be wholesomely Fabian but will instead take the form either of “public entertainment” or “some politically regressive sort of nationalism”. It will look less like Hillary than Donald:

Politicization is migrating to the right side of the political spectrum where anti-establishment parties are getting better and better at organising discontented citizens dependent upon public services and insisting on political protection from international markets.

In such long, precise, comfortless sentences, Streeck sets out the crises facing Britain, the US and the continent. His diagnosis is both political and economic, and it makes him what Chris Bickerton, a lecturer in politics at Cambridge, thinks might be “the most interesting person around today on the subject of the relationship between democracy and capitalism”.

Lehman Brothers headquarters in New York’s Times Square, 2008. Photograph: Mark Lennihan/AP

Which makes him the most interesting person on the most urgent subject of our times. Eight years after Lehman Brothers keeled over and nearly took the entire banking system down with it, capitalism remains broken. British workers are suffering their most severe pay squeeze in at least seven decades. And even though politicians and the policymakers have pulled on every lever – cuts, investment, housing boom, hundreds of billions pumped into the markets – still the engine refuses to purr. The failure is international: the Bank of International Settlements, the central banks’ central bank, warned a few months ago that “the global economy seems unable to return to sustainable and balanced growth”.

Not for the first time, the sandwich board-wearers are declaring the end of capitalism – but today Streeck believes they are right. In its deepest crises, he says, modern capitalism has relied on its enemies to wade in with the lifebelt of reform. During the Great Depression of the 30s, it was FDR’s Democrats who rolled out the New Deal, while Britain’s trade unionists allied with Keynes.

Compare that with now. Over 40 years, neoliberal capitalism has destroyed its opposition. When Margaret Thatcher was asked to give her greatest achievement, she nominated “Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.” The prime minister who declared “There is no alternative”, then did her damnedest to extirpate any such alternative. The result? The unions are withered, the independent tenants’ associations have disappeared along with the stock of council housing, the BBC is forever on the back foot, and local, regional and national newspapers are now the regular subjects of obituaries. A similar story can be told across the rich world.

Public discontent is fitful and fragmented, ready to fall into Trump’s tiny hands. Meanwhile, capitalism – unrestrained and unreformed – will die.

This isn’t the violent overthrow envisaged by Marx and Engels. In The Communist Manifesto, they argued that capitalism’s “gravediggers” would be the proletariat. Nearly 170 years later, Streeck is predicting that the capitalists will be their own gravediggers, through having destroyed the workers and the dissidents they needed to maintain the system. What comes next is not some better replacement but is more akin to the centuries-long rotting away of the Roman empire.

And, yes, his latest book is out just in time for Christmas. Not so long ago, such catastrophism would have been the stuff of Speakers’ Corner. Today, it goes right to the brokenness of politics.

Streeck is admired by the team around Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, and was invited to this year’s Labour conference in Liverpool (work commitments forced him to decline). One senior adviser described his relevance to British politics thus: “He is pretty blunt about how serious the situation is, for social democracy and capitalism.”

That we could modify capitalism towards equality and tame the beast – now those are utopian ideals

What gives Streeck’s analysis extra force is that he comes from the very establishment he now attacks. He has played many key roles: joint head of Germany’s top social science institute, an adviser in the late 90s to Gerhard Schröder’s government, one of Europe’s most eminent theorists of capitalism. While never a Third Way-er, he was friendly with David and Ed Miliband.

“I spent a long time in my life exploring the possibilities for an intelligent social democratic solution of the class conflict,” he explains over lunch. “The idea that we could modify capitalism towards equality and social justice. That we could tame the beast. Now I think those are more or less utopian ideals.”

He is thus a case study in the very thing he writes about: the demoralisation of centrist politics – and its radicalisation.

The great disillusionment came upon returning to Germany in 1995, after years teaching industrial relations in the US. It was the era of Germany being labelled “the sick man of Europe”, when one in five east German workers were unemployed. Through the metalworkers’ trade union, Streeck was invited to join a committee of trade unions, employers and government. Called the Alliance for Jobs (Bündnis für Arbeit), its task was to reform labour laws. Streeck believed this was “the last call for trade unions and social democracy”: the final chance to get more people into work without stripping workers of their rights.

“We came up with a good model, but everything we proposed was blocked – not just by the employers but by the unions, too.”

The Alliance fell apart and within a couple of years, Schröder had brought in the Hartz reforms – policies drawn up by a former Volkswagen executive that set up a new regime of workfare and benefit sanctions, and kicked the bottom out of the labour market.

A member of the Social Democratic Party, Germany’s counterpart to Labour, since the age of 16, Streeck finally cancelled his subs a few years ago. Would he still place himself as a social democrat? He quotes Keynes: “When the facts change, I change my mind.” In another interview he has described “the most urgent task for the left” as “sobering up”.

The constant sobriety might prove wearing, were it not for his easy companionship. Listening back to the recording, the primary sound is Streeck’s laughter – that and “Jajaja!”, a Bren gun enthusiasm for any new idea or argument.

He also gives good gossip. A “power breakfast” with financial policymakers and investment bankers is dismissed as “clueless and so stereoptypical. They complained about the stupidity of the masses who didn’t understand the expertise that someone like Alan Greenspan was able to bring to central banking.” This is the same Greenspan who, as head of the US central bank in the bubble years, believed financiers could regulate themselves.

On this trip he went to a conference on Brexit. “I was shocked by the unanimous sense of guilt.” One former British ambassador “began by saying we have to apologise to our foreign friends for the vote to leave Europe. I said, ‘You ought to be happy to have sent a warning to the European Union.’”

He sees the support for Brexit and Trump as stemming from the same source. “You have a growing group of all people, who, under the impact of neoliberal internationalisation, have become increasingly excluded from the mainstream of their society.

Visions of London wealth … Canary wharf financial district. Photograph: DBURKE / Alamy/Alamy

“You look out here,” He gestures out of the windows of the National Gallery, at the domes and columns of Trafalgar Square, “And it’s a second Rome. You walk through the streets at night and you say, ‘My God, yes: this is what an empire looks like’.” This is the land of what Streeck calls the Marktsvolk – literally, the people of the market, the club-class financiers and executives, the asset-owning winners of globalisation.

But this space – geographic, economic, political – is off-limits to the Staatsvolk: the ones who fly yearly on holiday rather than weekly on business, the downsized, the indebted losers of neoliberalism. “These people are being driven out of London. In French cities it’s the same thing. This both reinforces them as a political power structure, and puts them completely on the defensive. But one thing they do know is that conventional politics has totally written them off.” Social democrats such as the outgoing Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi are guilty, too. “They’re on the side of the winners.”

International flows of people, money and goods: Streeck accepts the need for all these – “but in some sort of directed, governable way. It has to be, otherwise societies dissolve”.

Those views on immigration landed him in another fight this summer, when he wrote an essay attacking Angela Merkel for her open-door policy towards refugees from Syria and elsewhere. It was a “ploy”, he said, to import tens of thousands of cheap workers and thus allow German employers to bring down wages. Colleagues accused him of spinning a “neoliberal conspiracy” theory and of giving cover to Germany’s far right. Streeck’s defence is simple: “It is impossible to protect wages against an unlimited labour supply. Does saying that make me some proto-fascist?”

What gives this back-and-forth a twist is the little-known fact that Streeck is himself the child of refugees. Both 25 years old when the second world war ended, his parents were among the 12 million displaced people to arrive from eastern Europe in West Germany. Streeck was born just outside Münster in a room requisitioned by the state from a shoemaker. His parents were poor. “I remember they stole vegetables from the fields and coal from passing trains.”

His mother was a Sudeten German in Czechoslovakia, who was given 24 hours’ notice to leave when the war ended, taking only what she could carry. After Streeck left home she began to study the Czech language. “It was a sense of ‘If I can’t go back there I at least want to speak the language of those people who now live where I used to’.”

Her son went to a grammar school founded by Martin Luther, where he was taught Greek and Latin and expected to become a theologian. Instead, he fell in with the then-illegal Communist party. Aged 16, he was in charge of organising the reading circle – “suppressed literature such as the Communist Manifesto and Rosa Luxemburg” – and held it at the local employers’ association “because no one would ever suspect”.

In 1968, he was a student radical at Frankfurt, “but I never had any truck with the ‘marijuana left’. I felt closer to the working class than to the pot-smoking classes”.

Now he lives with his wife in part of a farmyard of a castle in Brühl, a small town just outside Cologne. The retiree is still up by six every morning and at his desk for 8.30. “I have learned to write only till 1pm. After that I give myself over to academic intrigues.” And to novels: when we meet, he is reading I Hate the Internet, by Jarett Kobek, a Silicon Valley engineer who claims that the internet has “fucked up” his life.

After lunch, we cross the Thames to King’s College where Streeck is to deliver a lecture. There is more gossip, this time about Greek politics and the hollowing out of the Syriza government. As teenagers, Streeck’s class travelled to Greece to look at antiquities. Instead, he began reading local newspapers on the king’s attempts to chuck out prime minister Georgios Papandreou. “I wrote a report in the school newspaper that was almost entirely concerned with the emerging military dictatorship.” Sixty years later, he is working on a book about democracy in southern Europe.

The lecture room is packed, students spread across the floor and peering around the wall at Streeck, absent-mindedly playing with a paperclip and quoting Gramsci: “The old is dying and the new cannot be born. [pause] In this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms can appear.” In the lecture’s interval, a variety of students buy his books and hover about for him to sign them. At the end, a student asks: “what should the left do?”

Occupy protest in Frankfurt, 2011. Photograph: Arne Dedert/EPA

It is the same question I’d put a few hours earlier. Both times, Streeck warns he is about to disappoint us. To me he cites an Occupy protest in Frankfurt. Days before that, he says, thousands of police were deployed to Germany’s capital of finance. “The authorities were scared shitless. I think more such scariness must happen. They must learn that in order to keep people quiet they need extraordinary effort.”

No mention of ballot boxes; nor of any need for a bigger vision “because the others don’t have a blueprint”.

But, I say, Nigel Farage and the rest are at least pretending to have an answer.

“And we should criticise them.” The press always talks of a lack of business confidence, he says; now is the time for the voters to demonstrate a lack of public confidence.

The analogy doesn’t work and, listening back to the tape, I can hear agitation in my voice. A businessperson can go on an investment strike; he or she can hoard cash. Even if voters sat out an election, they would still face the consequences. Muslim mums would get their headscarves ripped off, a Polish man could get stabbed to death for going in the wrong kebab shop.

In a phone call a couple of weeks later, I press Streeck again. “If I look 10 or 20 years out, I don’t like what I see,” he says. Nor is he alone: he quotes a new book by the former head of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, and his projection of “great uncertainty” ahead.

But doesn’t he want something better than a new dark ages for his grandchildren? “If I am honest, now I am thankful for every passing year that is good and peaceful. And I hope for another one. Very short-term, I know, but those are my horizons.”