'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Sachin. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Sachin. Show all posts

Monday, 15 March 2021

Sunday, 17 November 2013

Sachin mania: it's about religion

Tendulkar: a cult figure if ever there was one © Associated Press

Enlarge

Sachin Tendulkar has finally retired. As I type this, there are a fair few letting out sighs of relief, because the sheer hype and hoopla surrounding his farewell Test series has left many feeling distinctly uncomfortable. The cynical nature of the BCCI's scheduling, the hyper-opportunism displayed by politicians and corporations, and the general hysteria of the crowds has left many decrying the spectacle as slightly unnerving.

As a Pakistani, I have been relatively immune to Sachin's appeal for most of my life. It was only in my more mature years that I came to support any Indian players at all. Even then, it was the likes of Rahul Dravid and perhaps Yuvraj Singh and MS Dhoni whom I admired, rather than Tendulkar.

Yet over the past few days, the backlash against the Sachin celebration has left me intrigued. Why were certain opinion-makers so visibly aghast at the treatment being accorded Sachin? Why were the sights of delirious crowds being countered with stats showing Sachin to be the 29th best batsman of all time?

The answer lies in an area that many people find to be naive at best and disastrous at worst. It is an area that carries significant political influence, and is always, always an incendiary topic to bring up. The answer lies in religion.

In Europe, and much of the developed world, historically, religion has been the cause of brutal and terrifying political battles over the centuries, which determined not just who ruled but also the intellectual world-view underpinning those governments. Consequently, speaking of religion in Western society can often invoke memories of violence and persecution, and can even be seen to be a resistance to progressive ideas.

In South Asia, religion has been and continues to be a major driver of violence and conflict. In a region that is one of the world's most diverse ethnically, religion often shows up as a fault line in a bewildering array of instances. Yet at the same time, religion (believe it or not) is also the reason why such distinct peoples have managed to live together for thousands of years. The idea of syncretism, which, broadly speaking, refers to the fusion of seemingly contradictory beliefs, is central to life in South Asia.

The prime example of such syncretism is found at festivals or melas held to commemorate the lives of famous saints. From Kabul to Chittagong, these are a ubiquitous feature of the subcontinent, and are attended by pilgrims from near and far. Most importantly, they witness an annihilation of conventional identities. So a saint from one religion has devotees from various faiths. You can have a Muslim saint whose shrine is visited by Hindus, Christians, Sikhs, and others.

It is impossible to distil and explain these practices in a few lines, but to put it simply, the reason such practices exist is because people believe that a truly holy person transcends conventional religious differences. Thus the revered saint becomes a pathway to a more immediate and direct bond with the divine - in a relationship that not only exists outside the regularly prescribed rituals, but is one that is only made possible due to the exalted life and efforts of the saint.

I think this is the context one needs to view Sachin's farewell in.

I am not taking the popular sentiment of calling him "god" and trying to run away with it, and I doubt many people consciously and spiritually see him as a saint on par with the rest. But the sentiment that underlines his retirement and the rapture he is generating cannot be seen as mere sycophancy, commercial exploitation, or celebrity-fuelled hysteria. Undoubtedly, all of these things play a part in this festival, but they are not what it is limited to.

When people ask why all this is being done for one person, or why Dravid, Sourav Ganguly and VVS Laxman didn't get such farewells, or why the FTP is being disrupted for one man, they are asking valid questions but ones that are irrelevant to this context. The debate about who was great and who wasn't ends here with the people. Because ultimately, this celebration is not for Sachin, it is for his devotees.

It is for the people who turned to him as a symbol of hope, as a symbol of perseverance. It is for the people who refused to give up because their Sachin hadn't. It is for the people who believed they could break barriers and limitations because Sachin had shown them it could be done. It is for the people who know that it is time to let go of someone they relied upon for their smiles and the unburdening of their sorrows.

Perhaps all this hype and obsession makes "cricket" fans feel uncomfortable. Perhaps there are fans despairing at this cult-like behaviour. Perhaps there are those who feel that all this undermines Sachin's own credibility. To all of them, I paraphrase the patron saint of cricket writers, Hazrat CLR James, when I say: "What do they know of Sachin, who only Sachin know?"

Wednesday, 24 July 2013

India's greatest cricket series - Recalling India's collective vow of silence

Trigger finger: SK Bansal gives Glenn McGrath out lbw on the last day of the 2001 Kolkata Test © Getty Images

Enlarge

Dave Richardson, the ICC chief executive, has called for the debate on neutral umpires to be reopened. It is a logical step too, since the nations that produce the best officials are unfairly deprived of the highest standards in officiating.

Umpires, their decisions, the DRS, and general human competence in the face of technology - all have come under the scanner during the ongoing Ashes series.

Ah, the Ashes! The fourth sequel to the greatest series ever - a title that is vehemently contested in India.

The greatest series ever? Neutral umpires? Combine the two and it serves as a natural trigger to take our minds back to 2001, a year before the Elite Panel of ICC umpires was appointed.

It seems a good time then to - if sheepishly rather than fondly, for reasons that will become clear soon - reminisce about the actual greatest series everwhen free men stood against the immortals and, unlike in the Battle of the Hot Gates, miraculously won the combat of the dust bowls.

India isn't so much the land of snake charmers as it is the land of unrivalled cricket fanatics. Fanaticism by definition leads to voluntary blindness and mutism. And from late afternoon onwards on the first day of the famousLaxman-Dravid Test match at Eden Gardens, the symptoms manifested themselves across the nation.

Harbhajan Singh had just become the first Indian to bag a Test match hat-trick, in circumstances so dubious that had Dean Jones been commentating, he'd still be muttering about the injustice in his sleep.

But, fortunately for us, we had the honour of being enthralled by the late Tony Greig, an Englishman whose brand of commentary every Indian could relate to: full of infectious enthusiasm that often came in the way of the facts. Thus, a cricket-mad nation perpetually charged up on adrenaline was further enthused by Tony's awe-inspiring words, and hope of immediate retrospection was lost.

Ricky Ponting was caught plumb in front. Adam Gilchrist smashed a ball that pitched miles (cricket metric) outside leg stump into his pads, but was given out lbw. The swashbuckling wicketkeeper, who had bludgeoned the Indian bowling en route to a match-winning ton at faster than a run a ball in the previous Test, left with a rueful smile.

And finally, Shane Warne was adjudged out caught, though replays were at the very least inconclusive, if not favouring the batsman's claim of a bump ball (though Sadagoppan Ramesh's unbelievable catch alone deserved that wicket, or so we convinced ourselves).

It was probably the most fortuitous hat-trick ever, and we were probably well aware of it at the time. But did we really care? Not a single bit.

An inherent detestation of anything Australian had clouded our senses. The visitors had won a record 16 Tests in a row. They had humiliated India in Mumbai, home of the nation's favourite son. Mark Waugh's paltry spin had made a mockery of batsmen who were born to play spin. Matthew Hayden and Gilchrist's combined onslaught had made a mockery of turning pitches. Ajit Agarkar had made a mockery of himself. Again.

But the tipping point was when Michael Slater - upset at his appeal for a catch being overturned - got in the face of Rahul Dravid, a cricketer for whom Indian mothers would be prepared to go to war, with rolling pins for swords.

And so, there was little remorse about the way India were thrown a lifeline.

The next morning, in offices, in schools, at bus stands, in shared cabs, in autorickshaws, on the footpaths, on news channels, in newspapers, the discussions would revolve around those five minutes of earth-shattering cricket the previous day.

Those who did dare point out India's extremely good fortune were shushed and banished. The implied embargo was added alongside the traditional laws of our cricket culture, which include: No remark can be accepted against the actions of Sachin Tendulkar, even if he unnecessarily paddle-sweeps his way back to the pavilion. And a Pakistani cricketer's communication skills ought to be laughed at irrespective of their educational backgrounds, and independent of how mediocre our own players' English-speaking skills are.

You were to muse over the Test match only in a 2:98 ratio, where 2% of the time is to be spent acknowledging the timing of the hat-trick and 98% of it admiring the lengthy batting partnership that followed two days later. If you were to watch the feat again, it ought to be done in 30 seconds and without replays. You were tacitly prohibited from indulging yourself in the finer details.

Six on-field umpires were used in the three Test matches. The three neutral umpires were experienced ones: David Shepherd, Peter Willey and Rudi Koertzen. All three were selected to be on the Elite Panel a year later, though Willey chose not to take up the option.

The three home umpires are worth looking at. S Venkataraghavan, who was later chosen as the only Indian umpire on the Elite Panel, stood in his 43rd Test in Mumbai. Unsurprisingly, the match went without a glitch.

SK Bansal, who stood in only his sixth Test (and incidentally his last) in Kolkata, and AV Jayaprakash, who stood in his ninth in Chennai, were the other two home umpires. Bansal, in particular, presided over a host of controversial decisions, which included the series-changing hat-trick calls and some key rulings that triggered Australia's second-innings collapse.

The speed at which his decisions were made - as Glenn McGrath found out when batting bravely to save the match in the final hour - suggested they were more impulsive than considered. He was an Indian after all, and only the most hard-hearted of professionals wouldn't have been affected by the screams of 100,000 people.

Such key moments, when the series was completely turned on its head, had more than just divine intervention about them. They also had a very human helping hand - or rather, finger. But a nation awash with patriotism and a renewed sense of pride chose to overlook factors that could possibly dampen their most famous victory.

The greatest series ever? Maybe. One of the greatest endorsements of the need for neutral and qualified umpires? Definitely.

Wednesday, 12 June 2013

Pick 'em early? The fate of young English talent.

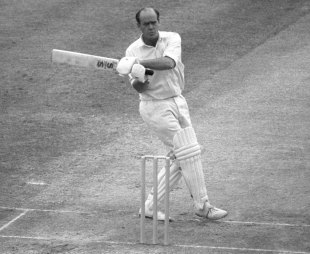

Brian Close: the youngest male cricketer to play Tests for England © PA Photos

Enlarge

It was a day for history at North Marine Road. Yorkshire, like the venerable Almanack, are celebrating their 150th anniversary this year. Sunday was also 50 years removed from the first of Geoffrey Boycott's 151 centuries in a Roses game at Bramall Lane, an occasion marked with the presentation of a framed scorecard. And then there was Matthew Fisher, all of 15 years and 212 days old, the youngest player to appear in a competitive county game since Charles Young, who turned out for Hampshire against Kent in 1867, aged 15 years and 131 days.

There is an inevitable melancholy about this great wash of time, refracted through the boys at either end of it. Young, a left-hand allrounder who was born in India, played 38 games across the next 18 years before slipping away into history. No one knows when or where he died, or the circumstances surrounding his end. He was here and then he was gone. We're left with his wickets and his runs and his odd little record, which may stand forever. Fisher is from an entirely different world and a more focused and intense game, yet prodigies always carry with them a chance of unfulfilment that can be unsettling.

Fifteen, you think, that's just too early, isn't it, however good you may be. For a start, it is such a brief span. Boycott had been retired for 11 years by the time Fisher was born, and no doubt Geoffrey could (and perhaps has) told the young man how fleeting those years can feel.

Yorkshire know a prodigy when they see one. Their 2nd XI keeper Barney Gibson was 15 years and 27 days old when he played against Durham University. Tim Bresnan got a Sunday League game as a 16-year-old. They had the young Sachin, of course, and before him Kevin Sharp, who seemed set for greatness after making a double-hundred for Young England and appearing in the first team at 18.

Then there was Brian Close, a man whose legend exists on different terms to those that his precocity seemed sure to dictate. Born in the same town, Rawdon, as Hedley Verity, he played Under-18 cricket at the age of 11, appeared for Leeds United and England youth as an amateur footballer and was considered bright enough to have attended Oxford or Cambridge had he chosen that path. Instead he became the youngest man ever to play for England in a Test match, in July 1949 at the age of 18, whilst in the process of completing the "double" of 1000 runs and 100 wickets in his first season (another record). Had the world known then that Close would make his final Test appearance almost 27 years later it might have imagined a new Leviathan had come, yet he played just 22 times for England.

In its place, Close's fame is based around his unyielding toughness, the brilliance of his captaincy (six wins and a draw in his seven Tests as England skipper; sacked after being accused of time-wasting in a game for Yorkshire) and his ability to nurture young players both in cricket and in life. Perhaps some of that understanding came from his earliest years, and the burden that they bestowed. He was by almost any measure a wonderful player, almost 35,000 runs, 1171 wickets and 800 catches batting left-handed and bowling right, and yet his first season casts its long shadow.

We are programmed to think that the earlier a talent emerges, the bigger it must be. That is not always the case. It will certainly not be rounded enough to offer anything other than promise, and promise is ephemeral stuff, available only for the briefest of moments. Matthew Fisher has promise, and our good wishes. What he needs most now is simply time.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)