'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Malala. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Malala. Show all posts

Thursday, 10 February 2022

Sunday, 23 November 2014

Arundhati Roy: goddess of big ideas

Arundhati Roy’s fans have been waiting for a follow-up to her Booker-prize winning debut novel since 1997. Meanwhile she has thrown herself into political activism – raising hackles among India’s growing bourgeoisie with fierce polemics against capitalism. A second novel is promised – but will she ever get it finished?

Like India and Walt Whitman, Arundhati Roy contains multitudes. She is, however, far from large. Small, delicately boned, a beguiling mixture of piercing dark eyes and bright easy smile, she is a warm presence. She turns 53 tomorrow and the grey tint to her curls lends depth to a still strikingly youthful face. Looking at her, it’s not hard to detect the author of the richly empathetic The God of Small Things, her debut, Booker-prize winning novel about family life in Kerala, that John Updike described as a “massive interlocking structure of fine, intensely felt details”.

That was 17 years ago and photos from that period show a captivating figure, at once shy and fiercely proud, wary and utterly self-possessed. The book was a huge international hit and the publishing world readied itself to cash in on a phenomenal new talent, galvanised by the fact that so photogenic an author would be a dream to market.

But the follow-up novel didn’t arrive. Instead Roy directed her considerable energies towards political activism, most especially in India where, despite her success, she has remained. It was a path that has led her to express solidarity with groups – such as Kashmiri separatists and Maoist guerrillas – that are seen by many Indians, with some reason, as terrorists. As a result Roy has become a controversial figure, an outspoken heroine in certain radical quarters, but loathed by large sections of Indian society, not least Hindu nationalists.

She has also become a prolific essayist and polemicist. She currently has two extended, book-length essays out. One, entitled The Doctor and the Saint, is an examination of caste, a subject she explored in The God of Small Things, and it forms the long introduction to a new edition of BR Ambedkar’s classic work The Annihilation of Caste. Roy’s essay traces the difficult relationship between Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi. She portrays the neglected Ambedkar – born an “untouchable” – as the true hero of India’s poor, while Gandhi is controversially depicted as a self-dramatising defender of the status quo.

The other essay is called Capitalism: A Ghost Story. It’s written in a very different style from The Doctor and the Saint, which, for all its contentious opinions, is a carefully constructed argument. By contrast Capitalism reads like an extended rant, strident, intemperate, conspiratorial, and relentlessly one-eyed in its outlook. The shrill prose is hard to reconcile with the softly spoken middle-aged woman sitting opposite me in the Soho offices of her publishers.

Her basic argument is that the reforms that liberated India’s economy in the early 1990s and thrust it into the global marketplace may have created a vibrant new middle class, but have been devastating for the country’s poor. She writes of the “800 million who have been impoverished and dispossessed to make way for us [the 300 million members of the middle class]”.

The poor in India are of course not a recent creation. It’s been said that India’s historic problem was the redistribution of poverty, whereas now the issue is the redistribution of wealth. As Roy makes clear, there are vast and intolerable inequalities in today’s India. But the implication of her words is that to make 300 million Indians richer, 800 million Indians have become poorer in real, rather than relative, terms. As she doesn’t supply any supporting evidence for this claim in the book, I ask her if that’s what she means.

“What happens,” she says, “is that statistically people keep playing games with the poverty line. It’s not that people get richer or poorer but they keep moving the line up and down redefining what poorer means.”

She then goes on to say that you only have to visit the suffering villages of India to see the terrible plight of the poor, in particular the mass suicides of farmers whose land has been destroyed by mineral exploitation and industrialisation. This may be true, but has the rapid growth in India’s middle class caused the poor to become poorer?

She continues talking about access to water, the drying up of land etc, until I push her once again on what seems to me a crucial matter of fact. “Well, I think so,” she says finally. “For example, just things like food grain intake has actually reduced.”

This is true, though there are various arguments put forward to explain the drop, including the increase in the consumption of other foods. But there is also compelling evidence to suggest that, while India has become a much wealthier country over the last couple of decades, a hefty percentage of its population continues to experience low employment, malnutrition and other major social deprivations. It’s just that Roy never really gets to grip with the evidence.

She prefers a scattergun approach in which she attacks everything from philanthropy and the “hegemony of the United States” to NGOs funded by Coca-Cola. You could easily get the idea, for example, that arms dealing was a function of capitalism – yet there is no mention of Russia (the biggest arms exporter) or China (the third biggest). Similarly she quotes Pablo Neruda’s poem attacking the Standard Oil Company but makes no mention that he was an unabashed cheerleader for Stalinism when he wrote it. When I ask her about the omission she says she’s written about Stalinism in another essay and doesn’t want to keep repeating herself.

It’s the sort of screed that will bring head-nodding agreement from her core anti-capitalist audience, but it will do little, or at least not enough, to persuade those who genuinely want to know whether or not the new India, for all its many flaws, is an improvement on the old.

She’s used to this sort of criticism, and her answer is that it’s not a subject that she can be dispassionate about. Dry, academic analysis doesn’t alter the conditions of the poor, so someone needs to raise the temperature, invoke some much-needed shame and outrage.

But her detractors argue that Roy’s posturings do nothing to help the poor either. Her fellow novelist and essayist Aatish Taseer wrote in 2011 in the online cultural magazine the Nervous Breakdown: “I don’t think she’s a friend of the poor at all. She would like to doom them to a permanent state of picturesque poverty… The people who get her into the streets [ie in protest] are the new middle classes. This class, still among the most fragile in India, people who have newly emerged from the most dire conditions, are despicable to her. She mocks their clothes; their trouble with English; she hates their ambitions.”

Indeed Roy writes of the “aggressive, acquisitive ambition” of the middle class in Capitalism. Is Taseer on to something?

“Well look,” she replies, unflustered, “obviously mine is a very definite point of view and there are many people who disagree with me vehemently. The only thing I will say is that I’m not a lone operator. Most of what I’ve written is to do with being in solidarity with many resistance movements. I’m not at the front of it. I’m not preaching to the poor what they should be thinking. I’m learning from their arguments.”

Naturally Roy’s wealth exposes her to accusations of hypocrisy. She lives alone in the exclusive Jor Bagh district of New Delhi in a large apartment. Aren’t the acquisitively ambitious simply seeking to gain the material comforts she has in abundance?

“I don’t come from a privileged background, I just happened to write a book that sold a lot. My mother was literally dying. She had nothing. She left her drunk husband. She started a school. I left home at 16, I lived on the streets. I had nothing. Then I wrote a book. I lived for a long time, yes, with a man who had privileged parents but then that had nothing to do with me.”

This seems like a slightly romantic summary of her early life. She was born Suzanna Arundhati Roy in north-east India to a Syrian Christian, Mary, who is still alive. Her father, a Bengali Hindu, was an alcoholic who managed a tea plantation. The marriage ended when Roy was two years old. Her mother took her and her older brother to Tamil Nadu and then to Kerala, where her mother, who suffered from asthma, set up an independent school.

Roy was sent to boarding school where she gained a reputation as an indefatigable debater. From there she went to secretarial college, which she quit at 16, moving to Delhi to study at the architectural school. She lived with her boyfriend at the time in a slum, then after a spell in Goa, worked for the National Institute of Urban Affairs, where she met her husband, Pradip Krishen, a widowed former history professor and Oxford graduate from a wealthy background.

The couple made several documentaries and films together, in the first of which Roy played the female lead. But eventually she became dispirited with the elitist film world and spent more time writing, leading eventually to the publication of The God of Small Things in 1997. It was a literary sensation that went on to sell more than 6m copies worldwide.

In a vital sense, as Roy says, her background and material circumstances, whatever they are, should not be the means to assess her ideas. “I’ve never understood the logic that if you’re privileged you should take the point of view of the privileged and argue for more privilege.”

Yet in Capitalism she writes of being compromised by connections with the corrupting worlds of corporations: “But which of us sinners was going to cast off the first stone? Not me, who lives off royalties from corporate publishing houses.”

What does that mean? She breaks out into a big smile. “Yeah, I’ve also thought about that. I was just thinking, living off royalties from corporate publishing houses? In fact those corporate publishing houses are making money off me, and giving me 5%!”

She laughs at herself and says that perhaps she got that wrong. “The thing is no one is pure. I am certainly not a pure saint who lives in a loincloth and eats goat’s cheese and doesn’t have sex and says ‘I’m poor’”, she says in an obvious dig at Gandhi. “It’s crap.”

Moreover, she is no armchair revolutionary, cooped up in the safe confines of her apartment. She does go to dangerous places and she does make powerful enemies: Hindu nationalists, dam builders, mineral extractors, large corporations and the Indian military. And despite a great many threats, she is not easily intimidated.

But danger runs both ways. The picture Roy paints of India is of a vast military occupation, a colonial suppression enacted by the Indian state on its own people. She speaks of hundreds of thousands of troops stationed in secessionist Kashmir and the vicious paramilitary operations in central India against the Maoist or “Naxalite” guerrillas.

In Walking with the Comrades, her book about joining up with the Maoists, she wrote about a Congress politician called Mahendra Karma, whom she said was responsible for orchestrating a campaign of murder, rapes and displacement in the Bastar region. In May 2013 Maoist guerrillas killed Karma, stabbing him 78 times, and 24 other people, including 11 other Congress members, in a truly gruesome attack on a convoy. When asked to comment immediately after the assault, Roy refused to speak.

Incidents such as these have prompted the charge that she is a dilettante, a literary tourist who can beat a retreat whenever it suits her. If that’s true then it’s also a fact that India’s democracy is riven by nepotism and corruption and violence and it suits many who are getting rich to look the other way. The statements Roy makes are often provocative, naive and arguably counterproductive, but the presiding nationalistic silence is perhaps more worthy of condemnation.

And the issue on which India has learned to be most tight-lipped is that of caste. It’s a subject on which Roy has always been refreshingly vocal, quick to remind those who might wish to forget of the immovable social structure that underpins Indian society. InThe Doctor and the Saint she returns to the theme but this time she sets it against two different visions of reform: Gandhi’s and Ambedkar’s.

Gandhi wanted to abolish the designation of “Untouchables”, the lowest caste that is today referred to as Dalit. But Ambedkar wanted to get rid of the caste system in its entirety. Although she had always been suspicious of the Gandhi cult, she was largely ignorant of the dispute between Ambedkar and Gandhi before a publisher asked her to write an introduction to The Annihilation of Caste.

“I thought I’d just write three pages of politeness and give it to him,” she says. “Then I started to read and I was shocked by what I was reading and it turned into a huge thing.”

Gandhi emerges as a backward-looking egomaniac who had to be dragged into modernity by the more ambitious and radical Ambedkar. The respected historian Ramachandra Guha, who is in the middle of a two-part biography of Gandhi, has taken Roy to task for “selectively quoting Gandhi out of context [so] that she can paint him as a slow-moving reactionary”.

Guha, whose earlier work looked at forestry in northern India, has clashed with Roy before over her environmental advocacy, which he described as “self-indulgent” and “self-contradictory”. “Ms Roy’s tendency to exaggerate and simplify, her Manichean view of the world, and her shrill, hectoring tone, have given a bad name to environmental analysis,” he wrote back in 2000.

She dismissed his criticism back then as “smug”. She says that she’s quoted Gandhi from 1893 to 1948, “across his adult life. Of course every quote has to be selective. I can’t quote the whole nine volumes.” She says that “it’s dishonest to suggest that Gandhi was an incrementalist or a man of his times”. And in any case, she adds, Guha is a Brahmin, the caste that is at the top of the social hierarchy – if you like, the ruling class.

It has been argued by some that it’s unfettered capitalism that has done most to undermine caste in India, but Roy notes that only a tiny percentage of marriages are cross-caste. She writes that the only way caste can be annihilated is if “those who call themselves revolutionary develop a radical critique of Brahminism”. I quote her a statement from a well-known Indian writer and ask her to guess who it is. The author speaks of his Brahmin identity as being crucial in giving him a sense of “dignity” and through it the ambition not to settle for “some badly paid government job”.

She puts her hands over her face and says “Pankaj?”

Pankaj Mishra, who is now based in London, has built a formidable reputation as radical critic of imperialism, ever vigilant to the incidence of western racism both on a geopolitical and personal level. He was also the first publisher to champion The God of Small Things, when he worked for HarperCollins in India, and thus a longstanding friend of Roy’s. Is he on the revolutionary side of the argument?

“On this one, I don’t think so,” she says. “There are a lot of critiques about many Brahmins who at some point do want to mention that they are Brahmins. The issue is a very vexed one. Look at all the major politburo members, including the Maoists, they are usually Brahmins.”

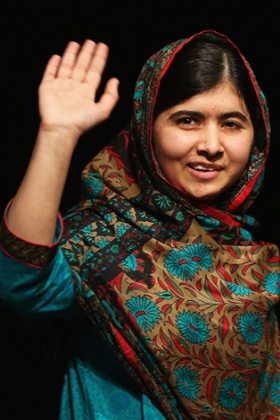

You sense that one of the reasons Arundhati was drawn to reappraise Gandhi is the consensus he enjoys as an embodiment of decency and tolerance. She has recently caused a stir for downplaying another widely admired figure, Malala Yousafzai. After she gave a TV interview in which she suggested Malala was a pawn in game of global politics, the Pakistan writer Pervez Hoodbhoy wrote an article asking why it was that Malala bothered many on the left, citing Roy as an example.

“I have no doubt she did something wonderful,” she says. “But that was not the point I was trying to make.” She says she wanted to draw attention to the fact that Dalit women are similarly mistreated in India but are never heard about. But that doesn’t make Malala a puppet. She stood up against male oppression. Isn’t that an unambiguously good thing?

“I don’t think you can isolate Malala and say ‘Oh this is wonderful.’” Why not? “I don’t think this world of prizes and awards is an innocent world. It is loaded and it’s precious to suggest it’s not.” She thinks Malala’s Nobel peace prize was an extension of the politically corrupt process that awarded one to Obama, whom she characterises as a warmonger, adding, “I’m not trying to take anything away from Malala.”

But of course she is.

I admire her willingness to confront sacred cows, but can’t help thinking that she sees dark conspiracies where sometimes nobler intentions lie. And in her rush to embrace the oppressed, she can blur the lines between victim and perpetrator.

Enough of the politics. What about fiction? There have been rumours going back to 2007 that she is writing a novel.

“I have been working on it for quite a few years,” she acknowledges. “If those characters are still hanging around in my house, swinging their legs and smoking their cigarette butts, they’re not going to go away, so there must be something there.”

Yet she says she put the novel aside to write The Doctor and the Saint. Writing non-fiction is for her a tense and urgent business. She has to get it out. “It’s like the body doesn’t have room for its organs,” she says, and reading her non-fiction one can see what she means.

She is a different person altogether when writing fiction, which she says she’s able to relax into. “I don’t mean because it’s easy to write but I trust its rhythms and I don’t have to get it out there. There’s no urgency. It’s like cooking, it takes its time. I rather like the idea of just living inside it and not coming out of it.”

That’s an idea that will torment all those millions who have been waiting so many years for her second novel. It may also trouble those critics of her polemical work who hope that she’ll return to fiction at the earliest opportunity. But if there is one thing that is certain about the multifaceted Roy, she will continue to do what she wants to do when she wants to do it.

Tuesday, 16 October 2012

A wake-up call for Pakistan's broken society

Karamatullah K Ghori

The barbaric attempt on the life of a 14-year-old schoolgirl last Tuesday by Taliban terrorists has spawned a state of trauma and national mourning in Pakistan. It's unlike other incidents that have hit the tragedy-prone country with a devastating frequency in recent years.

Malala Yusafzai, the innocent victim of the Pakistani Taliban's bloodlust, rose to prominence three years ago when, as an 11-year-old from the picturesque Swat Valley, she challenged the Taliban edict that girls shouldn't get an education. The Taliban, with their archaic, stone-age mentality, were then in control of Swat, and the Pakistan Army had just mounted a major military offensive against them. The militants had torched scores of schools for girls and threatened to deface with acid burns any girl seen going to a school.

The brave and indomitable Malala - whose father runs a private school for girls in Mingora, the administrative seat of Swat - had publicly defied the Taliban obscurantism by reminding their religious brigade that education was her birthright as both a Pakistani and a Muslim. She had the gumption to remind them that what they were demanding of her, and every other Pakistani girl, flew in the face of the Prophet Muhammad's categorical command that pursuit of knowledge was incumbent upon every Muslim man and woman.

Malala's bravado made her a celebrity; she became an icon to those who abhorred the Taliban's anachronistic and wayward interpretation of their religion. Once the Taliban brigands had been driven out of Swat, Malala was showered with government recognition and accolades. She became a standard-bearer of the Pakistani secularists and religious moderates who loathed the Taliban's craving to turn the clock back to the Middle Ages and deny the benefits of education to half the country's population.

However, for the revanchist Taliban, whose bloodlust is apparently insatiable and who believe in settling every issue at the point of a gun, Malala had become a marked person, irrespective of the fact that she was just a child.

It was not that Malala was not conscious of the danger she faced at the hands of the barbarians she had brazenly challenged on their own turf. In an interview with the British Broadcasting Corp a year ago - when she was still basking in the spotlight of fame and popular recognition - she had so stated:

The situation in Swat was normal until the Taliban appeared and destroyed the peace of Swat. They started their inhuman activities; they slaughtered people in the squares of Mingora, and they killed so many innocent people. Their first target was schools, especially girls' schools. They blasted so many girls' schools - more than 400 schools and more than 50,000 students suffered under the Taliban. We were afraid the Taliban might throw acid on our faces, or might kidnap us. They were barbarians; they could do anything.The "barbarians" managed to get back to their quarry and shoot her, in broad daylight in Mingora when she and her classmates were returning home from their school in a bus. It has shocked Pakistan's 180 million people out of their wits that, despite the military establishment's touted claims that it had purged Swat of the Taliban scourge, the pestilence has not only staged a comeback butwith a bang by settling scores with its well-known nemesis. It does not, apparently, bother the conscience of the bloodthirsty avengers that their nemesis was just 14.

The Pakistani people are shell-shocked, not only at the daring of the Taliban but much more at the appalling failure of the country's military and civil establishments to provide security to a brave little girl who was known to be a marked target in the Taliban book. The country's political leadership had cheered Malala's courage to take on the Taliban jackals in their lair but apparently did precious little to save her from the reach of their predatory revenge.

For the Pakistani intelligentsia and the infamous "silent majority" the shock is, however, anchored in something much larger than the hourly media sound bites keeping them up to date on Malala's medical condition, or the dismaying pictures from her bedside at the Combined Military Hospital in Rawalpindi where Pakistan's top-notch doctors and surgeons were fighting hard to save her life. (On Monday, Malala was ferried to Britain in an air ambulance provided by the United Arab Emirates government for special medical treatment and care.)

The trauma of Pakistan's thinking and chattering classes is focused on the larger question: Why did this happen? How could a society as traditional and ritualistic as Pakistan's - where women are sheltered and protected with special attention because of common perception of their being the weaker gender - allow a frenzied band of religious zealots like the Taliban to acquire so much power and authority as to become a menace to everyone - men, women and even children?

The answer, or answers, to this and related questions are of course well known to any Pakistani with his thinking cap on his head; it's another matter entirely to state the answer loud and clear.

The scourge of the Taliban has become a men-eating and children-devouring monster, not overnight but because of the laxity the whole society of Pakistan has been showing to this menace over a long period.

The genesis of the Taliban is generally traced to the Afghan struggle against the Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. The religious-minded zealots were plied with money and weapons by all those - Pakistan and its Arab and Western friends included - who thought that these firebrand mujahideen inspired by the religious sense of martyrdom could knock the ground from under the feet of the Russians. They did. But once that feat was achieved, the genie refused to go back into the bottle.

Pakistan virtually committed hara-kiri by treating the Taliban with kid gloves and allowing them to dig their heels into Pakistan's welcoming soil. The military and political establishment was daydreaming that the Taliban would provide strategic "depth" to Pakistan, vis-a-vis Afghanistan, and give a free hand to its forces against the "real enemy", India.

However, to the Taliban there couldn't be a more fertile place to sow the seeds of their archaic version of Islam than Pakistan's moribund society, already plagued by a decaying feudal system and afflicted with mendacity, corruption and wanton illiteracy.

The rest, as they say, is history. The Taliban have feasted on the inadequacies and glaring contradictions of Pakistan's broken society, where the word of mouth of a half-baked mullah carries more weight with hordes of illiterate masses than the writ of the government.

The rational segment of the Pakistanis - woefully fewer in number than the legions of faux messiahs with ready-made potions of elixir to cure the nation's festering wounds - have known for long that the menace lies within the body politic of Pakistan. The brazen attempt on the life of a 14-year-old social activist - whose crime in the eyes of her predatory assassins was that she preached education for girls of Pakistan - should be an eye-opener to anyone inclined to stem the rot.

Since the enemy is within, the battle against it will have to be waged by the Pakistanis themselves. They must take on the genie unleashed by them because of their weird logic and convoluted sense of religion. The time to act is now; delay will only escalate the cost and whet the appetite of the monsters threatening to bring down the ramparts of Pakistan.

Karamatullah K Ghori is a retired Pakistani ambassador and career diplomat, now a freelance columnist and commentator. He may be reached at K_K_ghori@yahoo.com.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)