'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Tuesday, 26 August 2025

Wednesday, 28 August 2024

Saturday, 10 August 2024

Sunday, 4 August 2024

Friday, 2 August 2024

Thursday, 1 August 2024

‘Nobody knows what I know’: how a loyal RSS member abandoned Hindu nationalism

As a young man, Partha Banerjee was on course to become a senior member of the RSS, the organisation that has pushed Indian politics towards extreme religious nationalism. Then, after 40 years within its ranks, he quit. Why?

Running a finger over a row of books in a Delhi library one afternoon, I stopped at a title that promised danger. The stacks were abundant in books like True Story of the RSS, RSS Misunderstood and Is RSS the Enemy?, which often turned out to be self-published polemics that were too long, however short they were. This one was different. On its front was the full title: In the Belly of the Beast: The Hindu Supremacist RSS and the BJP of India, An Insider’s View. I read the first page, and then the next, slowly, with rising giddiness. Not long after, I was beside a Sikh gentleman at his photocopying machine. What pages, he asked. Everything, I said.

In the long hour that followed, I wondered if the book’s presence on these shelves was an oversight. This was the closest that any writer had come to describing the organisation from within. That night I swallowed its contents whole, scanned a copy for myself to store in several places for safekeeping, and wrote to its author. We mailed, and then scheduled a video call, and then arranged to meet two months later, when he travelled to India from the US to alert people to the dangers of the RSS before the 2024 elections began.

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s members have long seen themselves as servants to an imaginary Hindu motherland that stretches from the Middle East to the far east. Its members would go to any lengths to protect this ideal from imagined threats. It was an RSS man who murdered Gandhi in January 1948. Forty-five years later, the RSS was one of the key forces behind the demolition of the Babri mosque, an event that triggered riots in which thousands of people were killed. There is no official list of members, but the RSS is usually said to be 4 million strong. The Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), the party that rules India at present, is the RSS’s political arm. Since its foundation in 1925, the organisation has existed as a kind of LinkedIn for the rootless, or a talent scout for people of a certain nationalist temperament; Narendra Modi, the prime minister, was a product of the organisation.

On the day we met, I waited for the author, whose name is Partha Banerjee, in a wide lane outside a mall in eastern Kolkata. I noticed him in the distance: a small man in a blue ikat-patterned kurta clutching a shopping bag bulging with vegetables. He had kind eyes behind his glasses, and his hair was short and grey. I followed him down one street and then another to his small flat. A maid brought out mangoes and sweets and placed them on a small table between us.

Partha told me he had left the RSS behind almost 40 years ago, and he said it as if he had firmly closed the door to that chapter of his life. But RSS people like to say that an RSS man will always be an RSS man, and there is a reason for this – it seduces through community and family, exerting a gravitational force on individuals. That was why, even though he had left the RSS, he thought about it often. He was once an insider marked for future greatness. Now, thanks to his book, he was an outcast. Its critique of the organisation was so clear-eyed that his father, an unbending RSS man, distanced himself from him. “He was completely heartbroken,” Partha said. “We stopped talking to each other for a very long time.”

Partha remembered his father fondly. As a parent, Jitendra Banerjee was an honest man who valued education, made time for his son’s cricket and football matches, and enjoyed taking him to the cinema. But as Partha now saw, Jitendra was also “completely racist, Islamophobic and fascist”. These aspects of him were plain to see – in what he read, what he said, in the values he brought home to the family. “I would hear from my father that communists and communism are evil, Islam was evil and Christianity was evil. I was reading RSS magazines and newspapers that were completely full of hatred. I did not know it was hatred because I thought it was true. I was made to believe that what I was reading and hearing was the ultimate reality.”

In the 1950s, Jitendra worked as a secretary in an outpost of the RSS’s brand new political wing, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh. Partha recalled the racket Jitendra’s typewriter made as he churned out party correspondence that would be delivered by hand. It was a small workplace, and energised with audacious dreams of a Hindu nation.

There was work, but little if any money for the rank and file, Partha said. The cost of Jitendra’s commitment to the RSS was borne by his wife and children. “My father gave up everything, a good academic career, a decent well-to-do family, their homes, mortal pleasures, everything,” Partha told me. “My mother suffered greatly because of that. I suffered greatly because of that. We ended up living in poverty all our lives. But that was the RSS.”

That was the RSS. The organisation’s members placed great store by suffering, maintaining not only a ledger of their own sacrifice but a complete accounting of everyone they knew. Years after Partha followed his father into the RSS, and then wrote his way out of it, he too was touched by this habit. And so while he remembered his father ignoring his financial responsibilities, and remembered that other members also “starved sometimes”, he saw nobility in a voluntary renouncing of comfort. “They were not greedy, they were not liars, they were not corrupt,” he said. “They were like saints.”

That was why he became a member and stayed with them for decades. He wanted me to understand that while he did not support Islamophobia, disparaging Dalits and gender discrimination, the people he knew who formed the RSS’s most loyal cadre “were very honest personally”. The purity of their hatred was the result of “following their own doctrines honestly”, he said. Another former RSS volunteer told me something similar: “They peddled hate, but did it very, very sincerely. It was almost like God’s work.”

The traces of scepticism that lingered within Partha were his mother’s doing. She came from a family of Indian National Congress supporters, the party of Nehru, and her distaste for the RSS was so strong that Jitendra rarely discussed politics at home. She was uneducated, Partha said, but her family had led her towards the Congress’s largely secular outlook. She watched with despair her son’s decision to follow his father, afraid he would abandon rationalism and spirituality for the intoxication of religion. “My mother never liked the social patriarchs and the chauvinist big talkers of the RSS,” Partha wrote. They inflated lost men, women and children with stories, and used a man for his energy and his time, and when he was done, they were done with him, she said.

Jitendra knew this to be true, but he did not feel exploited. He told his son that his work for the RSS was for the motherland, and this God-given duty was all the sustenance he needed. This baffled his son, because Jitendra was not a religious man. “His faith was abstract,” Partha said. “He would never participate in religious functions, but it was like: ‘Hindus must be strong, and we must come together, and we will become militant Hindus, and only with these weapons can we bring our country together, this country that is only for Hindus and no one else.’”

Partha believed that his mother had been right. After Jitendra died in 2017, Partha visited an RSS office in Kolkata to meet with old-timers who had known him as a child. He spoke up for his father, reminding them of Jitendra’s sacrifice: he had left college for them, rebuilt the organisation in Bengal after Gandhi’s murder by an RSS man and the subsequent crackdown on the organisation, he had burned incriminating documents when Indira Gandhi suspended civil liberties and sent her officers after the RSS, and had gone to jail for them. He argued that Jitendra deserved a worthy memorial for his evangelism and his translations. But he found them reluctant.

His father’s last decades were spent in reflection on his life and choices, and in this isolation he finally gave himself permission to openly admire the work of the poet Rabindranath Tagore, whom the RSS had once forbidden him from reading. Occasionally, he put on his dhoti and kurta to attend a special RSS meeting, but he had otherwise grown distant from those ideas. He had questions about the group’s involvement in the razing of the Babri Masjid in 1992 and in the pogroms of 2002 in Gujarat.

“He wasn’t the same old adamant arrogant RSS man,” Partha said. He had mellowed. In the end, 15 or 16 veterans showed up for the funeral, and there was a brief mention of his death in the RSS’s Bengali journal, Partha said. It wasn’t much in return for a life.

Partha had been six years old when Jitendra first led him to a shakha, a place where RSS men met to discuss matters of cultural importance and exercise together. Every neighbourhood had a shakha, such as a park or an open ground, and it was as much a place of gathering as a reminder of the local RSS’s strength. It was 1962. Partha was quickly pulled into the orbit of the shakha’s routines and the lives of its members. He played games, sang songs and heard stories. Every activity had mythological references, or was somehow related to Hindu culture. There was no room for western games such as cricket or football. The RSS’s teachers assumed the role of intellectual mentors, but the education they imparted was primarily based on the teachings of a single religion. “You’re not talking about Albert Einstein, or Charles Darwin, or climate change,” Partha said. They spoke of Muslims in the usual derogatory way, he said, and discussed the role that men and women were traditionally assigned: men were natural leaders, women were supporters. By the time he was nine or 10, Partha had located within himself the desire to beat up a couple of Muslim children at school. The people around him seemed to think it was fine, but he did not disclose the matter to his mother, afraid of what she would do to him.

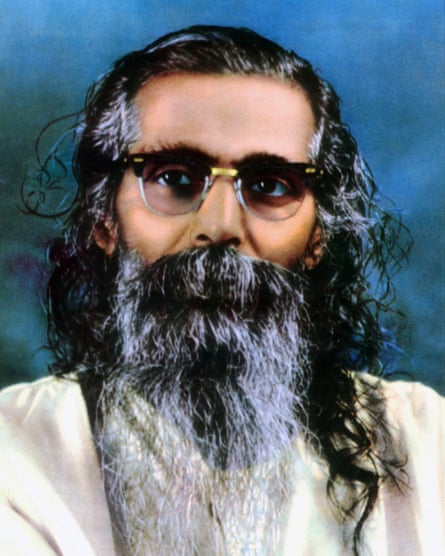

One time, MS Golwalkar, the RSS supreme leader, heard Partha leading prayers in mangled Sanskrit and summoned him to his room. After some questions about his father and his studies, he ordered him to take a crash course with a senior RSS leader to fix his pronunciation. “I was being groomed that way,” recalled Partha.

Between the late 1960s and early 70s, growing responsibility led Partha to believe that he was destined for a higher office within the organisation. His bosses sent word up the chain that he was a rare worker: he carried out orders without question, and was a capable recruiter to the cause. The positive impressions of him accumulated, and he was designated the education officer of his shakha. In his late teens, he encouraged hundreds of children from his north Kolkata neighbourhood to join the RSS.

When new recruits visited, Partha would absorb the details of their life. He would ask what school they went to, the class they were in, where they lived, what their father did, how many siblings they had. Their preferences, quirks and secrets were all subjects of interest to him. In those first days he was careful not to talk of religion or politics. In that cloak of harmlessness and respectability he would ask the recruit’s permission to meet his family. An invitation for tea or a meal would be extended. In his experience, families were delighted to have an RSS functionary visit them at home. By making their concerns his own, he could demonstrate the limitless resources of the vast body he represented. “You find out how he’s doing in school, what exams he’s doing for his school final,” Partha recalled. “Are you doing all right with maths? Do you have a teacher? I can send someone to help you with maths. I’ll find someone who is good at maths in the RSS and send him to help him out at home for free.”

For those susceptible, this was a fast process. “Very quickly this kid, this newcomer, is not a newcomer any more. He’s a part of the RSS family. You have to show people sincerely, not in a fake way, that I like you as a brother, and I really care for your life and your family. You start believing me, and you know that I am someone that you can count on. That I am going to be there for you in times of need. I won’t give you money, but I will look out for you. And your mother knows that you’re not going to be watching internet porn after school. You’re going to be in good company with a bunch of kids who play together, sing together and talk about the country and the nation. And if you did not go to RSS, then you would basically be like a stray kid, like on the roadside, talking to a bunch of kids and smoking and doing drugs and womanising.”

Despite his many successes, it was still only a small proportion of conversion attempts that succeeded. Of every 10 recruits, Partha estimated that nine were “yanked out before you know it” by families sympathetic to Congress or the Communist party. The ones who remained were largely illiterate and unaware. “If you are not an enlightened family, I am your enlightenment,” he said, referring to the RSS. “I’m teaching you about Hinduism, I’m teaching you about [the Hindu monk] Vivekananda, I’m teaching you about India and its many different states and its many different languages and songs.”

I asked him what would happen if someone asked a question. He replied that there would be a reply of some kind, but the questioner would often lack the critical skills necessary to assess the response – not merely because of their young age, but because of the quality of their education. His dismissiveness about the intellectual capacity of the RSS’s rank and file was startling. Partha did not blame the RSS’s members, but he did not spare them either. “Ninety to 95% of its members are practically brainless idiots”, he said to me.

He believed that the arrangement worked well for the organisation. It needed followers to carry out commands across its vast network. “There is no process of questioning anything; you just follow with folded hands.” Besides inventing answers to earnest questions, it was common practice to group a troublesome question with two or three queries so that it was forgotten in the reply, a former RSS volunteer who served as city secretary in Shillong said. “They would say things like, ‘We’ll talk to you later,’ or, ‘We’ll speak with you in private.’”

At 15 or 16, Partha was invited to the annual officers’ training camp, and then assigned leadership of the local shakha. He continued the regimented traditions that thousands before him had been given. In their little fiefdoms where few people witnessed their practices, Partha and the leaders diligently unfolded and hoisted the swallow-tail orange flag, the focal point of their devotion. Whether the wind brought it alive or whether it sagged, they prayed to the flag and performed their exercises as if it was watching. The fabric was drenched in meaning: eternity, authority, purity, the sun’s illumination, a cleansing fire. In cities and villages at approximately the same time, Partha’s peers in the RSS were engaged in the same activity. They drew a kind of strength from this synchronicity, a motivation from the feeling of participation in a larger common activity. Neither weather nor violence interrupted the shakha’s routines. The shakha was the front desk of an enormous conglomerate, and its flag had to flutter and be saluted, and become the centre of worlds.

Partha rose to joint secretary of the RSS’s student wing. He made speeches across the state, fixed meetings, assessed the group’s popularity on other campuses and went on marches across Kolkata.

During the Emergency, a 21-month period of martial law imposed by India’s prime minister in the mid-1970s, the RSS was outlawed as it had been after Gandhi’s assassination. But, just as before, its members continued to meet under the guise of other activities, and new organisations with innocuous names continued its work. Partha helped establish one such organisation. It was “the RSS in camouflage”, he said. “We all worked under a non-political platform with an innocuous name: the Bandemataram Chaterbesh Committee.” The name was associated with the national anthem and deep-rooted feelings of revolution and nationalism. “We even brought in a judge from the Calcutta high court to be the president. When it was the RSS, he could not join because he was the chief justice. But who can say no to the Bandemataram Chaterbesh Committee?”

His work brought him renown. He had done enough for people to know him not just as Jitendra’s son, but as a man marked for stardom. And then, in 1981, when it was all going so well, he surprised them by leaving.

Partha had been growing detached from the RSS. As to why, his answers were a jumble. He explained that his mother’s painful cancer had made him reconsider his life. Additionally, his questions to the RSS’s leadership went unanswered. He had been reading Tagore, watching films by the great directors Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, and chatting with leftist friends. In the talking, reading and watching, he grew – and grew apart. Then he moved to the US. “I left behind hundreds of very good friends whom I may never see again in my life,” he said. In his book, he described the departure as a cleansing – a dip in the Ganges that absolved him of his sins.

While he worked on his PhD in a rural part of the US, he did not feel the urge to check up on home, as new students normally did. Even if he wanted to, there was no internet. Then in 1995 he moved to Albany, New York, and caught up on the news from India.

“I was shocked,” he said.

The Hindu future he grew up hearing about from his father, in shakhas and in training camps, was suddenly here. He was convinced of it when he read about possessed men, joyous men, standing atop the dome of the Babri mosque before bringing it all down. “I felt they were materialising their long-term doctrine that India was for Hindus.”

Partha corresponded about Hindu fundamentalism with writers and researchers, and read independent riot investigations. Many of them pointed to truths he knew and understood intimately – riots were incited by newly formed communal organisations that consisted of people associated with the RSS and its political arm, the BJP. The organisations were not usually RSS, but the people were, and they operated as representatives of newly formed bodies.

As he read what had been written about the organisation, he realised they were outsider perspectives. Scholars understood the RSS theoretically, but they did not really understand it. “I thought, ‘Oh, my God, I have to do something about it because I know them so well, and nobody knows what I know.’” He wrote his book, a slim volume based on his experiences. He did not explain his work in any detail, instead focusing on the small things about life within the RSS. But it contained enough for his father to feel betrayed by the book.

The possibility that Modi’s party would win a third term in 2024 had convinced Partha to visit India for longer than usual. He wanted to travel the country and tell people all about the RSS. “They are turning India upside down into a fascist state,” he said. “Their entire functioning has been so boring and dull and drab that it has helped them to build a very powerful national network of people who cannot think. And people who cannot think are prone to following the dictates of leaders without question. That is the RSS’s main strength. Nobody really knows much about it. How many people read history? A vast majority of Indians simply do not have any idea what the RSS is all about. Most people are illiterate in the first place, and what do they know about Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Tojo, the second world war, the SS and Brownshirts?

“There is absolutely no discussion in mainstream media. How many times have you actually heard mainstream media discuss RSS history, for example? Never, never. Because it is so uncomfortable that it is definitely going to create a conflict between media corporations and RSS-BJP leadership, and they have figured this out really quickly.” The party in power and its ideological parent insisted that they were independent of each other, an explanation that Partha thought so little of that he hyphenated them.

As a result, from his home in the US, he had watched the familiar blights spread: misleading information, made-up histories and armed fascists setting the rules of civic life. He said that racists who had been, “you know, in hibernation”, were now fully awake under the new regime, whose encouragement of unrest had made them virtually arms of the government.

All of this had worked to Modi’s advantage, he said. He thought of the writer Aldous Huxley’s description of an ideal totalitarian state, a condition he thought applied to Indians: they were inside a prison whose walls they could not see.

Adapted from The New India: The Unmaking of the World’s Largest Democracy, published by Abacus on 8 August and available at guardianbookshop.com

.png)