'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label cancer. Show all posts

Showing posts with label cancer. Show all posts

Saturday, 16 January 2021

Wednesday, 7 June 2017

Even moderate drinking can damage the brain, claim researchers

Nicola Davis in The Guardian

Drinking even moderate amounts of alcohol can damage the brain and impair cognitive function over time, researchers have claimed.

While heavy drinking has previously been linked to memory problems and dementia, previous studies have suggested low levels of drinking could help protect the brain. But the new study pushes back against the notion of such benefits.

“We knew that drinking heavily for long periods of time was bad for brain health, but we didn’t know at these levels,” said Anya Topiwala, a clinical lecturer in old age psychiatry at the University of Oxford and co-author of the research.

Alcohol is a direct cause of seven forms of cancer, finds study

Writing in the British Medical Journal, researchers from the University of Oxford and University College London, describe how they followed the alcohol intake and cognitive performance of 550 men and women over 30 years from 1985. At the end of the study the team took MRI scans of the participants’ brains.

None of the participants were deemed to have an alcohol dependence, but levels of drinking varied. After excluding 23 participants due to gaps in data or other issues, the team looked at participants’ alcohol intake as well as their performance on various cognitive tasks, as measured at six points over the 30 year period.

The team also looked at the structure of the participants’ brains, as shown by the MRI scan, including the structure of the white matter and the state of the hippocampus – a seahorse-shaped area of the brain associated with memory.

After taking into account a host of other factors including age, sex, social activity and education, the team found that those who reported higher levels of drinking were more often found to have a shrunken hippocampus, with the effect greater for the right side of the brain.

While 35% of those who didn’t drink were found to have shrinkage on the right side of the hippocampus, the figure was 65% for those who drank on average between 14 and 21 units a week, and 77% for those who drank 30 or more units a week.

The structure of white matter was also linked to how much individuals drank. “The big fibre tracts in the brain are cabled like electrical wire and the insulation, if you like, on those wires was of a poorer quality in people who were drinking more,” said Topiwala.

In addition, those who drank more were found to fare worse on a test of lexical fluency. “[That] is where you ask somebody to name as many words as they can within a minute beginning with a certain letter,” said Topiwala. People who drank between seven and 14 units a week were found to have 14% greater reduction in their performance on the task over 30 years, compared to those who drank just one or fewer units a week.

By contrast, no effects were found for other tasks such as word recall or those in which participants were asked to come up with words in a particular category, such as ‘animals.’

Expert reaction to the the study was mixed. While Elizabeth Coulthard, consultant senior lecturer in dementia neurology at the University of Bristol, described the research as robust, she cautioned that as the study was observational, it does not prove that alcohol was causing the damage to the brain.

Even small amounts of alcohol increase a woman's risk of cancer

In addition, the majority of the study’s participants were men, while reports of alcohol consumption are often inaccurate with people underestimating how much they drink – an effect that could have exaggerated the apparent impact of moderate amounts of alcohol.

Dr Doug Brown, director of research and development at Alzheimer’s Society said that the new research did not imply that individuals should necessarily turn teetotal, instead stressing that it was important to stick to recommended guidelines.

In 2016, the Department of Health introduced new alcohol guidelines in the UK, recommending that both men and women drink no more than 14 units of alcohol each week – the equivalent of about six pints of beer or seven 175ml glasses of wine.

“Although this research gives useful insight into the long-term effects that drinking alcohol may have on the brain, it does not show that moderate alcohol intake causes cognitive decline. However, the findings do contradict a common belief that a glass of red wine or champagne a day can protect against damage to the brain,” said Brown.

Drinking even moderate amounts of alcohol can damage the brain and impair cognitive function over time, researchers have claimed.

While heavy drinking has previously been linked to memory problems and dementia, previous studies have suggested low levels of drinking could help protect the brain. But the new study pushes back against the notion of such benefits.

“We knew that drinking heavily for long periods of time was bad for brain health, but we didn’t know at these levels,” said Anya Topiwala, a clinical lecturer in old age psychiatry at the University of Oxford and co-author of the research.

Alcohol is a direct cause of seven forms of cancer, finds study

Writing in the British Medical Journal, researchers from the University of Oxford and University College London, describe how they followed the alcohol intake and cognitive performance of 550 men and women over 30 years from 1985. At the end of the study the team took MRI scans of the participants’ brains.

None of the participants were deemed to have an alcohol dependence, but levels of drinking varied. After excluding 23 participants due to gaps in data or other issues, the team looked at participants’ alcohol intake as well as their performance on various cognitive tasks, as measured at six points over the 30 year period.

The team also looked at the structure of the participants’ brains, as shown by the MRI scan, including the structure of the white matter and the state of the hippocampus – a seahorse-shaped area of the brain associated with memory.

After taking into account a host of other factors including age, sex, social activity and education, the team found that those who reported higher levels of drinking were more often found to have a shrunken hippocampus, with the effect greater for the right side of the brain.

While 35% of those who didn’t drink were found to have shrinkage on the right side of the hippocampus, the figure was 65% for those who drank on average between 14 and 21 units a week, and 77% for those who drank 30 or more units a week.

The structure of white matter was also linked to how much individuals drank. “The big fibre tracts in the brain are cabled like electrical wire and the insulation, if you like, on those wires was of a poorer quality in people who were drinking more,” said Topiwala.

In addition, those who drank more were found to fare worse on a test of lexical fluency. “[That] is where you ask somebody to name as many words as they can within a minute beginning with a certain letter,” said Topiwala. People who drank between seven and 14 units a week were found to have 14% greater reduction in their performance on the task over 30 years, compared to those who drank just one or fewer units a week.

By contrast, no effects were found for other tasks such as word recall or those in which participants were asked to come up with words in a particular category, such as ‘animals.’

Expert reaction to the the study was mixed. While Elizabeth Coulthard, consultant senior lecturer in dementia neurology at the University of Bristol, described the research as robust, she cautioned that as the study was observational, it does not prove that alcohol was causing the damage to the brain.

Even small amounts of alcohol increase a woman's risk of cancer

In addition, the majority of the study’s participants were men, while reports of alcohol consumption are often inaccurate with people underestimating how much they drink – an effect that could have exaggerated the apparent impact of moderate amounts of alcohol.

Dr Doug Brown, director of research and development at Alzheimer’s Society said that the new research did not imply that individuals should necessarily turn teetotal, instead stressing that it was important to stick to recommended guidelines.

In 2016, the Department of Health introduced new alcohol guidelines in the UK, recommending that both men and women drink no more than 14 units of alcohol each week – the equivalent of about six pints of beer or seven 175ml glasses of wine.

“Although this research gives useful insight into the long-term effects that drinking alcohol may have on the brain, it does not show that moderate alcohol intake causes cognitive decline. However, the findings do contradict a common belief that a glass of red wine or champagne a day can protect against damage to the brain,” said Brown.

Friday, 19 August 2016

Creative Visualisation - Your Mind Can Keep You Well

PSI TEK

Did you know that it is only recently that medical doctors have accepted how important the power of the mind is in influencing the immune system of the human body? Many decades passed before these men of science decided to test the proposition that the brain is involved in the optimum functioning of the different body systems. Recent research shows the undeniable connection --the link-- between mind and body, which challenged the long-held medical assumption. A new science called psychoneuroimmunology or PNI, the study of how the mind affects health and bodily functions, has come out of such research.

A psychologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Lean Achterberg, suggests that emotion may form the link between mind and immunity. “Many of the autonomic functions connected with health and disease,” she explains,” are emotionally triggered.”

Exercises which encourage relaxation and mental activities such as creative visualization, positive thinking, and guided imagery produce subtle changes in the emotions which can trigger either a positive or a negative effect on the immune system. This explains why positive imaging techniques have resulted in dramatic healings in people with very serious illnesses, including cancer.

OMNI magazine claims (February, 1989), in a cover article entitled “Mind Exercises That Boost Your Immune System”:

“As far back as the Thirties, Edmund Jacobson found that if you imagine or visualize yourself doing a particular action - say, lifting an object with your right arm - the muscles in that arm show increased electrical activity. Other scientists have found that imagining an object moving across the sky produces more eye movements than visualizing a stationary object.”

One of the most dramatic applications of imagery in coping with illness is the work of Dr. Carl Simonton, a radiation cancer specialist in Dallas, Texas. “By combining relaxation with personalized images,” reports OMNI magazine, “he has helped terminal cancer patients reduce the size of their tumors and sometimes experience complete remission of the disease.”

Many of his patients have benefited from this technique. It simply shows how positive visualization can help alleviate - if not totally cure - various diseases including systemic lupus erythomatosus, migraine, chronic back pain, hyperthyroidism, high blood pressure, hyper-acidity, etc.

However, individual differences have to be taken into consideration when discussing each patient’s progress. It’s understandable that individuals have varying abilities to visualize or create mental images clearly; some people will benefit more from positive-imagery techniques than others

Nevertheless, if visualization can help people overcome diseases, it could possibly help healthy individuals keep their immune system in top shape. Says OMNI magazine: “Practicing daily positive-imaging techniques may, like a balanced diet and physical exercise routine, tip the scales of health toward wellness.”

The Simonton process of visualization for cancer

Dr. Carl Simonton, a radiation cancer specialist, and his wife, Stephanie Matthews-Simonton, a psychotherapist and counselor specializing in cancer patients, have developed a special visualization or imaging technique for the treatment of cancer which is now popularly known as the Simonton process. Ridiculed at first by the medical profession, the Simonton process is now being used in at least five hospitals across the United States to fight cancer.

The technique itself is the height of simplicity and utilizes the tremendous powers of the mind, specifically its faculty for visualization and imagination, to control cancer. First, the patient is shown what a normal healthy cell looks like. Next, he is asked to imagine a battle going on between the cancer cell and the normal cell. He is asked to visualize a concrete image that will represent the cancer cell and another image of the normal cell. Then he is asked to see the normal cell winning the battle against the cancer cell.

One youngster represented the normal cell as the video game character Pacman and the cancer cell as the “ghosts” (enemies of Pacman), and then he saw Pacman eating up the ghosts until they were all gone.

A housewife saw her cancer cell as dirt and the normal cell as a vacuum cleaner. She visualized the vacuum cleaner swallowing up all the dirt until everything was smooth and clean.

Patients are asked to do this type of visualization three times a day for 15 minutes each time. And the results of the initial experiments in visualization to cure cancer were nothing short of miraculous. Of course, being medical practitioners, Dr. Simonton and his psychologist wife were aware of the placebo effect and spontaneous remission of illness. As long as they were getting good results with the technique, it didn’t seem to matter whether it was placebo or spontaneous remission.

The Simontons also noticed that those who got cured had a distinct personality. They all had a strong will to live and did everything to get well. Those who didn’t succeed had resigned themselves to their fate.

While the Simontons were exploring the motivation of cancer patients, they were also looking into two interesting areas of research at that time: biofeedback and the surveillance theory. Both areas had something to do with the influence of the mind over body processes. Stephanie Simonton explains in her book The Healing Family:

In biofeedback training, an individual is hooked up to a device that feeds back information on his physiological processes. A patient with tachycardia, an irregular heartbeat, might be hooked up to an oscilloscope, which will give a constant visual readout of the heartbeat. The patient watches the monitor while attempting to relax…when he succeeds in slowing his heartbeat through his thinking, he is rewarded immediately by seeing that fact on visual display.

The surveillance theory holds that the immune system does in fact produce ‘killer cells’ which seek out and destroy stray cancer cells many times in our lives, and it is when this system breaks down, that the disease can take hold. When most patients are diagnosed with cancer, surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy are used to destroy as much of the tumor as possible. But once the cancer is reduced, we wondered if the immune system could be reactivated to seek out and destroy the remaining cancer cells.

The Simontons reasoned that since people can learn how to influence their blood flow and heart rate by using their minds, they could also learn to influence their immune system. Later research proved their approach to be valid.

For instance, according to the Time-Life Book The Power of Healing, “chronic stress causes the brain to release into the body a host of hormones that are potent inhibitors of the immune system”. “This may explain why people experience increased rates of infection, cancer, arthritis, and many other ailments after losing a spouse.” Dr. R.W. Berthop and his associates in Australia found that blood samples of bereaved individuals showed a much lower level of lymphocyte activity than was present in the control group’s samples. Lymphocytes are a variety of white blood cells consisting of T cells and B cells, both critical to the action of the immune system. T cells directly attack disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and toxins, and regulate the other parts of the immune system. B cells produce antibodies, which neutralize invaders or mark them for destruction by other agents of the immune system.

The Power of Healing concludes: “The idea that there is a mental element to healing has gained acceptance within the medical establishment in recent years. Many physicians who once discounted the mind’s ability to influence healing are now reconsidering, in the light of new scientific evidence. All these have led some physicians and medical institutions toward a more holistic approach, to treating the body and mind as a unit rather than as two distinct entities. Inherent in this philosophy is the belief that patients must be active participants in the treatment of their illnesses.

Using visualization for minor ailments

Today, many scientific breakthroughs have proven that minor infections and viruses may be healed, or at least lessened in severity by employing mental techniques similar to those used by cancer patients who have successfully shrunk tumors through positive imaging or visualization.

The theory is that creative visualization can create the same physiological changes in the body that a real experience can. For example, if you imagine squeezing a lemon into you mouth, you will most likely salivate, the same way as when a real lemon is actually being squeezed into your mouth. Einstein once declared that, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

In the 1985 World Conference on Imaging, reports OMNI magazine (February 1989), registered nurse Carol Fajoni observed that “people who used imagery techniques to heal wounds recovered more quickly than those who did not. In workshops, the same technique has been used by individuals suffering from colds with similar results.” The process has been hailed as a positive breakthrough and is currently being used by more enlightened doctors, according to OMNI magazine.

Visualize that part of your body which is causing the problem. Then erase the negative image and instead picture that organ or part to be healthy. Let's say you have a sinus infection. Just picture your sinus passageways and cavities as beginning to unclog. Or if you have a kidney disorder, imagine a sick-looking kidney metamorphose into a healthier one.

“In trying to envision yourself healthy, you need not view realistic representations of the ailing body part. Instead, imagine a virus as tiny spots on a blackboard that need erasing. Imagine yourself building new, healthy cells or sending cleaning blood to an unhealthy organ or area.”

“If you have a headache, picture your brain as a rough, bumpy road that needs smoothing and proceed to smooth it out. The point is to focus on the area you believe is causing you to feel sick, and to concentrate on visualizing or imaging it to be well. The more clearly and vividly you can do this, the more effective the technique becomes.”

Another method for banishing pain was developed by Russian memory expert, Solomon V. Sherehevskii, as reported by Russian psychologist Professor Luria. To banish pain, such as a headache, Sherehevskii would visualize the pain as having an actual shape, mass and color. Then, when he had a “tangible” image of the pain in his mind, he would visualize or imagine this concrete picture slowly becoming smaller and smaller until it disappeared from his mental vision. The real pain disappears with it. Others have modified this same technique and suggest that you imagine a big bird or eagle taking the concrete image of the pain away. As it flies over the horizon, see it becoming smaller until it disappears from your view. The actual pain will disappear with it.

Of course, the effectiveness of this imaging technique depends on the strength of your desire to improve your health and your ability to visualize well. But there is no harm in trying it, because unlike drugs, creative visualization has no side effects.

Practice any of these visualization techniques three times a day for one week and observe your health improve.

Did you know that it is only recently that medical doctors have accepted how important the power of the mind is in influencing the immune system of the human body? Many decades passed before these men of science decided to test the proposition that the brain is involved in the optimum functioning of the different body systems. Recent research shows the undeniable connection --the link-- between mind and body, which challenged the long-held medical assumption. A new science called psychoneuroimmunology or PNI, the study of how the mind affects health and bodily functions, has come out of such research.

A psychologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Lean Achterberg, suggests that emotion may form the link between mind and immunity. “Many of the autonomic functions connected with health and disease,” she explains,” are emotionally triggered.”

Exercises which encourage relaxation and mental activities such as creative visualization, positive thinking, and guided imagery produce subtle changes in the emotions which can trigger either a positive or a negative effect on the immune system. This explains why positive imaging techniques have resulted in dramatic healings in people with very serious illnesses, including cancer.

OMNI magazine claims (February, 1989), in a cover article entitled “Mind Exercises That Boost Your Immune System”:

“As far back as the Thirties, Edmund Jacobson found that if you imagine or visualize yourself doing a particular action - say, lifting an object with your right arm - the muscles in that arm show increased electrical activity. Other scientists have found that imagining an object moving across the sky produces more eye movements than visualizing a stationary object.”

One of the most dramatic applications of imagery in coping with illness is the work of Dr. Carl Simonton, a radiation cancer specialist in Dallas, Texas. “By combining relaxation with personalized images,” reports OMNI magazine, “he has helped terminal cancer patients reduce the size of their tumors and sometimes experience complete remission of the disease.”

Many of his patients have benefited from this technique. It simply shows how positive visualization can help alleviate - if not totally cure - various diseases including systemic lupus erythomatosus, migraine, chronic back pain, hyperthyroidism, high blood pressure, hyper-acidity, etc.

However, individual differences have to be taken into consideration when discussing each patient’s progress. It’s understandable that individuals have varying abilities to visualize or create mental images clearly; some people will benefit more from positive-imagery techniques than others

Nevertheless, if visualization can help people overcome diseases, it could possibly help healthy individuals keep their immune system in top shape. Says OMNI magazine: “Practicing daily positive-imaging techniques may, like a balanced diet and physical exercise routine, tip the scales of health toward wellness.”

The Simonton process of visualization for cancer

Dr. Carl Simonton, a radiation cancer specialist, and his wife, Stephanie Matthews-Simonton, a psychotherapist and counselor specializing in cancer patients, have developed a special visualization or imaging technique for the treatment of cancer which is now popularly known as the Simonton process. Ridiculed at first by the medical profession, the Simonton process is now being used in at least five hospitals across the United States to fight cancer.

The technique itself is the height of simplicity and utilizes the tremendous powers of the mind, specifically its faculty for visualization and imagination, to control cancer. First, the patient is shown what a normal healthy cell looks like. Next, he is asked to imagine a battle going on between the cancer cell and the normal cell. He is asked to visualize a concrete image that will represent the cancer cell and another image of the normal cell. Then he is asked to see the normal cell winning the battle against the cancer cell.

One youngster represented the normal cell as the video game character Pacman and the cancer cell as the “ghosts” (enemies of Pacman), and then he saw Pacman eating up the ghosts until they were all gone.

A housewife saw her cancer cell as dirt and the normal cell as a vacuum cleaner. She visualized the vacuum cleaner swallowing up all the dirt until everything was smooth and clean.

Patients are asked to do this type of visualization three times a day for 15 minutes each time. And the results of the initial experiments in visualization to cure cancer were nothing short of miraculous. Of course, being medical practitioners, Dr. Simonton and his psychologist wife were aware of the placebo effect and spontaneous remission of illness. As long as they were getting good results with the technique, it didn’t seem to matter whether it was placebo or spontaneous remission.

The Simontons also noticed that those who got cured had a distinct personality. They all had a strong will to live and did everything to get well. Those who didn’t succeed had resigned themselves to their fate.

While the Simontons were exploring the motivation of cancer patients, they were also looking into two interesting areas of research at that time: biofeedback and the surveillance theory. Both areas had something to do with the influence of the mind over body processes. Stephanie Simonton explains in her book The Healing Family:

In biofeedback training, an individual is hooked up to a device that feeds back information on his physiological processes. A patient with tachycardia, an irregular heartbeat, might be hooked up to an oscilloscope, which will give a constant visual readout of the heartbeat. The patient watches the monitor while attempting to relax…when he succeeds in slowing his heartbeat through his thinking, he is rewarded immediately by seeing that fact on visual display.

The surveillance theory holds that the immune system does in fact produce ‘killer cells’ which seek out and destroy stray cancer cells many times in our lives, and it is when this system breaks down, that the disease can take hold. When most patients are diagnosed with cancer, surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy are used to destroy as much of the tumor as possible. But once the cancer is reduced, we wondered if the immune system could be reactivated to seek out and destroy the remaining cancer cells.

The Simontons reasoned that since people can learn how to influence their blood flow and heart rate by using their minds, they could also learn to influence their immune system. Later research proved their approach to be valid.

For instance, according to the Time-Life Book The Power of Healing, “chronic stress causes the brain to release into the body a host of hormones that are potent inhibitors of the immune system”. “This may explain why people experience increased rates of infection, cancer, arthritis, and many other ailments after losing a spouse.” Dr. R.W. Berthop and his associates in Australia found that blood samples of bereaved individuals showed a much lower level of lymphocyte activity than was present in the control group’s samples. Lymphocytes are a variety of white blood cells consisting of T cells and B cells, both critical to the action of the immune system. T cells directly attack disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and toxins, and regulate the other parts of the immune system. B cells produce antibodies, which neutralize invaders or mark them for destruction by other agents of the immune system.

The Power of Healing concludes: “The idea that there is a mental element to healing has gained acceptance within the medical establishment in recent years. Many physicians who once discounted the mind’s ability to influence healing are now reconsidering, in the light of new scientific evidence. All these have led some physicians and medical institutions toward a more holistic approach, to treating the body and mind as a unit rather than as two distinct entities. Inherent in this philosophy is the belief that patients must be active participants in the treatment of their illnesses.

Using visualization for minor ailments

Today, many scientific breakthroughs have proven that minor infections and viruses may be healed, or at least lessened in severity by employing mental techniques similar to those used by cancer patients who have successfully shrunk tumors through positive imaging or visualization.

The theory is that creative visualization can create the same physiological changes in the body that a real experience can. For example, if you imagine squeezing a lemon into you mouth, you will most likely salivate, the same way as when a real lemon is actually being squeezed into your mouth. Einstein once declared that, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

In the 1985 World Conference on Imaging, reports OMNI magazine (February 1989), registered nurse Carol Fajoni observed that “people who used imagery techniques to heal wounds recovered more quickly than those who did not. In workshops, the same technique has been used by individuals suffering from colds with similar results.” The process has been hailed as a positive breakthrough and is currently being used by more enlightened doctors, according to OMNI magazine.

Visualize that part of your body which is causing the problem. Then erase the negative image and instead picture that organ or part to be healthy. Let's say you have a sinus infection. Just picture your sinus passageways and cavities as beginning to unclog. Or if you have a kidney disorder, imagine a sick-looking kidney metamorphose into a healthier one.

“In trying to envision yourself healthy, you need not view realistic representations of the ailing body part. Instead, imagine a virus as tiny spots on a blackboard that need erasing. Imagine yourself building new, healthy cells or sending cleaning blood to an unhealthy organ or area.”

“If you have a headache, picture your brain as a rough, bumpy road that needs smoothing and proceed to smooth it out. The point is to focus on the area you believe is causing you to feel sick, and to concentrate on visualizing or imaging it to be well. The more clearly and vividly you can do this, the more effective the technique becomes.”

Another method for banishing pain was developed by Russian memory expert, Solomon V. Sherehevskii, as reported by Russian psychologist Professor Luria. To banish pain, such as a headache, Sherehevskii would visualize the pain as having an actual shape, mass and color. Then, when he had a “tangible” image of the pain in his mind, he would visualize or imagine this concrete picture slowly becoming smaller and smaller until it disappeared from his mental vision. The real pain disappears with it. Others have modified this same technique and suggest that you imagine a big bird or eagle taking the concrete image of the pain away. As it flies over the horizon, see it becoming smaller until it disappears from your view. The actual pain will disappear with it.

Of course, the effectiveness of this imaging technique depends on the strength of your desire to improve your health and your ability to visualize well. But there is no harm in trying it, because unlike drugs, creative visualization has no side effects.

Practice any of these visualization techniques three times a day for one week and observe your health improve.

Thursday, 18 August 2016

How do people die from cancer?

Ranjana Srivastava in The Guardian

Our consultation is nearly finished when my patient leans forward, and says, “So, doctor, in all this time, no one has explained this. Exactly how will I die?” He is in his 80s, with a head of snowy hair and a face lined with experience. He has declined a second round of chemotherapy and elected to have palliative care. Still, an academic at heart, he is curious about the human body and likes good explanations.

“What have you heard?” I ask. “Oh, the usual scary stories,” he responds lightly; but the anxiety on his face is unmistakable and I feel suddenly protective of him.

“Would you like to discuss this today?” I ask gently, wondering if he might want his wife there.

“As you can see I’m dying to know,” he says, pleased at his own joke.

If you are a cancer patient, or care for someone with the illness, this is something you might have thought about. “How do people die from cancer?” is one of the most common questions asked of Google. Yet, it’s surprisingly rare for patients to ask it of their oncologist. As someone who has lost many patients and taken part in numerous conversations about death and dying, I will do my best to explain this, but first a little context might help.

Some people are clearly afraid of what might be revealed if they ask the question. Others want to know but are dissuaded by their loved ones. “When you mention dying, you stop fighting,” one woman admonished her husband. The case of a young patient is seared in my mind. Days before her death, she pleaded with me to tell the truth because she was slowly becoming confused and her religious family had kept her in the dark. “I’m afraid you’re dying,” I began, as I held her hand. But just then, her husband marched in and having heard the exchange, was furious that I’d extinguish her hope at a critical time. As she apologised with her eyes, he shouted at me and sent me out of the room, then forcibly took her home.

It’s no wonder that there is reluctance on the part of patients and doctors to discuss prognosis but there is evidence that truthful, sensitive communication and where needed, a discussion about mortality, enables patients to take charge of their healthcare decisions, plan their affairs and steer away from unnecessarily aggressive therapies. Contrary to popular fears, patients attest that awareness of dying does not lead to greater sadness, anxiety or depression. It also does not hasten death. There is evidence that in the aftermath of death, bereaved family members report less anxiety and depression if they were included in conversations about dying. By and large, honesty does seem the best policy.

Studies worryingly show that a majority of patients are unaware of a terminal prognosis, either because they have not been told or because they have misunderstood the information. Somewhat disappointingly, oncologists who communicate honestly about a poor prognosis may be less well liked by their patient. But when we gloss over prognosis, it’s understandably even more difficult to tread close to the issue of just how one might die.

Thanks to advances in medicine, many cancer patients don’t die and the figures keep improving. Two thirds of patients diagnosed with cancer in the rich world today will survive five years and those who reach the five-year mark will improve their odds for the next five, and so on. But cancer is really many different diseases that behave in very different ways. Some cancers, such as colon cancer, when detected early, are curable. Early breast cancer is highly curable but can recur decades later. Metastatic prostate cancer, kidney cancer and melanoma, which until recently had dismal treatment options, are now being tackled with increasingly promising therapies that are yielding unprecedented survival times.

But the sobering truth is that advanced cancer is incurable and although modern treatments can control symptoms and prolong survival, they cannot prolong life indefinitely. This is why I think it’s important for anyone who wants to know, how cancer patients actually die.

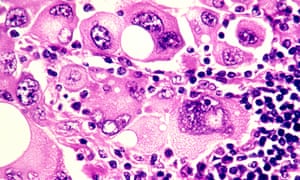

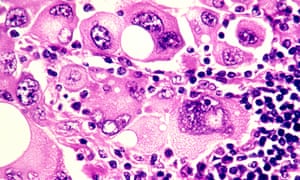

‘Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food’ Photograph: Phanie / Alamy/Alamy

“Failure to thrive” is a broad term for a number of developments in end-stage cancer that basically lead to someone slowing down in a stepwise deterioration until death. Cancer is caused by an uninhibited growth of previously normal cells that expertly evade the body’s usual defences to spread, or metastasise, to other parts. When cancer affects a vital organ, its function is impaired and the impairment can result in death. The liver and kidneys eliminate toxins and maintain normal physiology – they’re normally organs of great reserve so when they fail, death is imminent.

Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food, leading to progressive weight loss and hence, profound weakness. Dehydration is not uncommon, due to distaste for fluids or an inability to swallow. The lack of nutrition, hydration and activity causes rapid loss of muscle mass and weakness. Metastases to the lung are common and can cause distressing shortness of breath – it’s important to understand that the lungs (or other organs) don’t stop working altogether, but performing under great stress exhausts them. It’s like constantly pushing uphill against a heavy weight.

Cancer patients can also die from uncontrolled infection that overwhelms the body’s usual resources. Having cancer impairs immunity and recent chemotherapy compounds the problem by suppressing the bone marrow. The bone marrow can be considered the factory where blood cells are produced – its function may be impaired by chemotherapy or infiltration by cancer cells.Death can occur due to a severe infection. Pre-existing liver impairment or kidney failure due to dehydration can make antibiotic choice difficult, too.

You may notice that patients with cancer involving their brain look particularly unwell. Most cancers in the brain come from elsewhere, such as the breast, lung and kidney. Brain metastases exert their influence in a few ways – by causing seizures, paralysis, bleeding or behavioural disturbance. Patients affected by brain metastases can become fatigued and uninterested and rapidly grow frail. Swelling in the brain can lead to progressive loss of consciousness and death.

In some cancers, such as that of the prostate, breast and lung, bone metastases or biochemical changes can give rise to dangerously high levels of calcium, which causes reduced consciousness and renal failure, leading to death.

Uncontrolled bleeding, cardiac arrest or respiratory failure due to a large blood clot happen – but contrary to popular belief, sudden and catastrophic death in cancer is rare. And of course, even patients with advanced cancer can succumb to a heart attack or stroke, common non-cancer causes of mortality in the general community.

You may have heard of the so-called “double effect” of giving strong medications such as morphine for cancer pain, fearing that the escalation of the drug levels hastens death. But experts say that opioids are vital to relieving suffering and that they typically don’t shorten an already limited life.

It’s important to appreciate that death can happen in a few ways, so I wanted to touch on the important topic of what healthcare professionals can do to ease the process of dying.

In places where good palliative care is embedded, its value cannot be overestimated. Palliative care teams provide expert assistance with the management of physical symptoms and psychological distress. They can address thorny questions, counsel anxious family members, and help patients record a legacy, in written or digital form. They normalise grief and help bring perspective at a challenging time.

People who are new to palliative care are commonly apprehensive that they will miss out on effective cancer management but there is very good evidence that palliative care improves psychological wellbeing, quality of life, and in some cases, life expectancy. Palliative care is a relative newcomer to medicine, so you may find yourself living in an area where a formal service doesn’t exist, but there may be local doctors and allied health workers trained in aspects of providing it, so do be sure to ask around.

Finally, a word about how to ask your oncologist about prognosis and in turn, how you will die. What you should know is that in many places, training in this delicate area of communication is woefully inadequate and your doctor may feel uncomfortable discussing the subject. But this should not prevent any doctor from trying – or at least referring you to someone who can help.

Accurate prognostication is difficult, but you should expect an estimation in terms of weeks, months, or years. When it comes to asking the most difficult questions, don’t expect the oncologist to read between the lines. It’s your life and your death: you are entitled to an honest opinion, ongoing conversation and compassionate care which, by the way, can come from any number of people including nurses, social workers, family doctors, chaplains and, of course, those who are close to you.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Epicurus observed that the art of living well and the art of dying well were one. More recently, Oliver Sacks reminded us of this tenet as he was dying from metastatic melanoma. If die we must, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the part we can play in ensuring a death that is peaceful.

Our consultation is nearly finished when my patient leans forward, and says, “So, doctor, in all this time, no one has explained this. Exactly how will I die?” He is in his 80s, with a head of snowy hair and a face lined with experience. He has declined a second round of chemotherapy and elected to have palliative care. Still, an academic at heart, he is curious about the human body and likes good explanations.

“What have you heard?” I ask. “Oh, the usual scary stories,” he responds lightly; but the anxiety on his face is unmistakable and I feel suddenly protective of him.

“Would you like to discuss this today?” I ask gently, wondering if he might want his wife there.

“As you can see I’m dying to know,” he says, pleased at his own joke.

If you are a cancer patient, or care for someone with the illness, this is something you might have thought about. “How do people die from cancer?” is one of the most common questions asked of Google. Yet, it’s surprisingly rare for patients to ask it of their oncologist. As someone who has lost many patients and taken part in numerous conversations about death and dying, I will do my best to explain this, but first a little context might help.

Some people are clearly afraid of what might be revealed if they ask the question. Others want to know but are dissuaded by their loved ones. “When you mention dying, you stop fighting,” one woman admonished her husband. The case of a young patient is seared in my mind. Days before her death, she pleaded with me to tell the truth because she was slowly becoming confused and her religious family had kept her in the dark. “I’m afraid you’re dying,” I began, as I held her hand. But just then, her husband marched in and having heard the exchange, was furious that I’d extinguish her hope at a critical time. As she apologised with her eyes, he shouted at me and sent me out of the room, then forcibly took her home.

It’s no wonder that there is reluctance on the part of patients and doctors to discuss prognosis but there is evidence that truthful, sensitive communication and where needed, a discussion about mortality, enables patients to take charge of their healthcare decisions, plan their affairs and steer away from unnecessarily aggressive therapies. Contrary to popular fears, patients attest that awareness of dying does not lead to greater sadness, anxiety or depression. It also does not hasten death. There is evidence that in the aftermath of death, bereaved family members report less anxiety and depression if they were included in conversations about dying. By and large, honesty does seem the best policy.

Studies worryingly show that a majority of patients are unaware of a terminal prognosis, either because they have not been told or because they have misunderstood the information. Somewhat disappointingly, oncologists who communicate honestly about a poor prognosis may be less well liked by their patient. But when we gloss over prognosis, it’s understandably even more difficult to tread close to the issue of just how one might die.

Thanks to advances in medicine, many cancer patients don’t die and the figures keep improving. Two thirds of patients diagnosed with cancer in the rich world today will survive five years and those who reach the five-year mark will improve their odds for the next five, and so on. But cancer is really many different diseases that behave in very different ways. Some cancers, such as colon cancer, when detected early, are curable. Early breast cancer is highly curable but can recur decades later. Metastatic prostate cancer, kidney cancer and melanoma, which until recently had dismal treatment options, are now being tackled with increasingly promising therapies that are yielding unprecedented survival times.

But the sobering truth is that advanced cancer is incurable and although modern treatments can control symptoms and prolong survival, they cannot prolong life indefinitely. This is why I think it’s important for anyone who wants to know, how cancer patients actually die.

‘Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food’ Photograph: Phanie / Alamy/Alamy

“Failure to thrive” is a broad term for a number of developments in end-stage cancer that basically lead to someone slowing down in a stepwise deterioration until death. Cancer is caused by an uninhibited growth of previously normal cells that expertly evade the body’s usual defences to spread, or metastasise, to other parts. When cancer affects a vital organ, its function is impaired and the impairment can result in death. The liver and kidneys eliminate toxins and maintain normal physiology – they’re normally organs of great reserve so when they fail, death is imminent.

Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food, leading to progressive weight loss and hence, profound weakness. Dehydration is not uncommon, due to distaste for fluids or an inability to swallow. The lack of nutrition, hydration and activity causes rapid loss of muscle mass and weakness. Metastases to the lung are common and can cause distressing shortness of breath – it’s important to understand that the lungs (or other organs) don’t stop working altogether, but performing under great stress exhausts them. It’s like constantly pushing uphill against a heavy weight.

Cancer patients can also die from uncontrolled infection that overwhelms the body’s usual resources. Having cancer impairs immunity and recent chemotherapy compounds the problem by suppressing the bone marrow. The bone marrow can be considered the factory where blood cells are produced – its function may be impaired by chemotherapy or infiltration by cancer cells.Death can occur due to a severe infection. Pre-existing liver impairment or kidney failure due to dehydration can make antibiotic choice difficult, too.

You may notice that patients with cancer involving their brain look particularly unwell. Most cancers in the brain come from elsewhere, such as the breast, lung and kidney. Brain metastases exert their influence in a few ways – by causing seizures, paralysis, bleeding or behavioural disturbance. Patients affected by brain metastases can become fatigued and uninterested and rapidly grow frail. Swelling in the brain can lead to progressive loss of consciousness and death.

In some cancers, such as that of the prostate, breast and lung, bone metastases or biochemical changes can give rise to dangerously high levels of calcium, which causes reduced consciousness and renal failure, leading to death.

Uncontrolled bleeding, cardiac arrest or respiratory failure due to a large blood clot happen – but contrary to popular belief, sudden and catastrophic death in cancer is rare. And of course, even patients with advanced cancer can succumb to a heart attack or stroke, common non-cancer causes of mortality in the general community.

You may have heard of the so-called “double effect” of giving strong medications such as morphine for cancer pain, fearing that the escalation of the drug levels hastens death. But experts say that opioids are vital to relieving suffering and that they typically don’t shorten an already limited life.

It’s important to appreciate that death can happen in a few ways, so I wanted to touch on the important topic of what healthcare professionals can do to ease the process of dying.

In places where good palliative care is embedded, its value cannot be overestimated. Palliative care teams provide expert assistance with the management of physical symptoms and psychological distress. They can address thorny questions, counsel anxious family members, and help patients record a legacy, in written or digital form. They normalise grief and help bring perspective at a challenging time.

People who are new to palliative care are commonly apprehensive that they will miss out on effective cancer management but there is very good evidence that palliative care improves psychological wellbeing, quality of life, and in some cases, life expectancy. Palliative care is a relative newcomer to medicine, so you may find yourself living in an area where a formal service doesn’t exist, but there may be local doctors and allied health workers trained in aspects of providing it, so do be sure to ask around.

Finally, a word about how to ask your oncologist about prognosis and in turn, how you will die. What you should know is that in many places, training in this delicate area of communication is woefully inadequate and your doctor may feel uncomfortable discussing the subject. But this should not prevent any doctor from trying – or at least referring you to someone who can help.

Accurate prognostication is difficult, but you should expect an estimation in terms of weeks, months, or years. When it comes to asking the most difficult questions, don’t expect the oncologist to read between the lines. It’s your life and your death: you are entitled to an honest opinion, ongoing conversation and compassionate care which, by the way, can come from any number of people including nurses, social workers, family doctors, chaplains and, of course, those who are close to you.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Epicurus observed that the art of living well and the art of dying well were one. More recently, Oliver Sacks reminded us of this tenet as he was dying from metastatic melanoma. If die we must, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the part we can play in ensuring a death that is peaceful.

Thursday, 4 February 2016

The age of deference to doctors and elites is over. Good riddance

Mary Dejevsky in The Independent

There was something about the story of five-year-old Ashya King that went beyond the plight of this one small, sick child, wrapped up in his blanket and connected to a drip. It was not just the public relations savvy of his family: the elaborate preparations for their flight, recorded and posted on the internet that drew such all-consuming public interest. Nor was it only the drama of the police chase across Europe, and the nights spent in a Spanish prison. It was much more.

There was a profound clash of principles here at a junction of extremes: a child with a terminal brain tumour, a fixed medical consensus, and parents who hoped, believed, there could be another way.

You probably remember – I certainly do – how forcefully Ashya’s father, Brett, argued his case. He had, he said, set about learning all he could about treatment possibilities for his son’s condition on the internet and in medical journals and concluded that a particular form of therapy was superior to the one being offered by the NHS.

Now, 18 months on, Ashya King’s story has a sequel beyond the so-far happy ending of his recovery announced last March. The sequel is that the treatment his family fought for so hard has indeed been found to be superior to that generally offered by the NHS, and in precisely the ways that the Kings had argued. A study published in The Lancet Oncology – an offshoot of The Lancet – concluded that the proton beam therapy, such as Ashya eventually obtained in Prague, was as effective as conventional radiotherapy, but less likely to cause damage to hearing, brain function and vital organs, especially in children.

In one way, that should perhaps come as no surprise, given King’s claim to have scoured the literature. There is also room for caution. This was a relatively small study conducted in the US. There was no control group – with children, this is deemed (rightly) to be unethical – and harmful side-effects were reduced, not eliminated. But such is the nature of medical research, and the treatment decisions based on it. Things are rarely cut and dried; it is more a balance of probability.

This may be one reason why the Lancet findings had less resonance than might have been expected, given the original hue and cry about Ashya’s case. But my cynical bet is that if the study had shown there was essentially no difference between the two treatments, or that proton beams were a quack therapy potentially hyped for commercial advantage, sections of the NHS establishment would have been out there day and night, warning parents who might be tempted to follow the Kings’ path how wrong-headed they were, and stressing how the doctors had been vindicated.

Instead, there were low-key interviews with select specialists, who noted that three NHS centres providing the therapy would be open by April 2018. Until then, those (few) children assessed as suitable for proton beam treatment would continue to go to the United States at public expense. (Why the US, rather than Prague or elsewhere in Europe, is not explained.)

It may just be my imagination, but I sensed an attempt to avoid reigniting the passions that had flared over Ashya’s treatment at the time, and especially not to raise other parents’ expectations. But I don’t think the controversy should be allowed to rest so easily. The King family’s experience raised serious questions about the practice of medicine in the UK and the attitudes of the professionals to their patients. And these latest research findings on proton therapy mean that it still does.

When Brett King presented his arguments, he did so not just with understandable emotion, but with enviable lucidity. He patently understood what he was talking about. This treatment was there; he wanted to give it a go, and he was prepared to raise the funds to pay for it. To the medics, he may well have come across as difficult, and there were those who genuinely felt that he was acting against the best interests of his son. In that case, the arguments should have gone to court – as they had done with eight-year-old Neon Roberts and his contested cancer treatment half a year before. That the Kings are Jehovah’s Witnesses may also have cued particular caution.

However, what many, especially in the medical establishment, seem reluctant to recognise is that change is afoot in relations between the professional elite and the rest – and not only because the so-called “age of deference” is dead.

Increasingly, it seems, we lay people are invited to make choices, only to be censured, or worse, for making the “wrong” one. Lawyers, for instance, will repeatedly tell you that they offer only advice; it is up to us to act on it, or not. So it is, increasingly, in the NHS.

There was something about the story of five-year-old Ashya King that went beyond the plight of this one small, sick child, wrapped up in his blanket and connected to a drip. It was not just the public relations savvy of his family: the elaborate preparations for their flight, recorded and posted on the internet that drew such all-consuming public interest. Nor was it only the drama of the police chase across Europe, and the nights spent in a Spanish prison. It was much more.

There was a profound clash of principles here at a junction of extremes: a child with a terminal brain tumour, a fixed medical consensus, and parents who hoped, believed, there could be another way.

You probably remember – I certainly do – how forcefully Ashya’s father, Brett, argued his case. He had, he said, set about learning all he could about treatment possibilities for his son’s condition on the internet and in medical journals and concluded that a particular form of therapy was superior to the one being offered by the NHS.

Now, 18 months on, Ashya King’s story has a sequel beyond the so-far happy ending of his recovery announced last March. The sequel is that the treatment his family fought for so hard has indeed been found to be superior to that generally offered by the NHS, and in precisely the ways that the Kings had argued. A study published in The Lancet Oncology – an offshoot of The Lancet – concluded that the proton beam therapy, such as Ashya eventually obtained in Prague, was as effective as conventional radiotherapy, but less likely to cause damage to hearing, brain function and vital organs, especially in children.

In one way, that should perhaps come as no surprise, given King’s claim to have scoured the literature. There is also room for caution. This was a relatively small study conducted in the US. There was no control group – with children, this is deemed (rightly) to be unethical – and harmful side-effects were reduced, not eliminated. But such is the nature of medical research, and the treatment decisions based on it. Things are rarely cut and dried; it is more a balance of probability.

This may be one reason why the Lancet findings had less resonance than might have been expected, given the original hue and cry about Ashya’s case. But my cynical bet is that if the study had shown there was essentially no difference between the two treatments, or that proton beams were a quack therapy potentially hyped for commercial advantage, sections of the NHS establishment would have been out there day and night, warning parents who might be tempted to follow the Kings’ path how wrong-headed they were, and stressing how the doctors had been vindicated.

Instead, there were low-key interviews with select specialists, who noted that three NHS centres providing the therapy would be open by April 2018. Until then, those (few) children assessed as suitable for proton beam treatment would continue to go to the United States at public expense. (Why the US, rather than Prague or elsewhere in Europe, is not explained.)

It may just be my imagination, but I sensed an attempt to avoid reigniting the passions that had flared over Ashya’s treatment at the time, and especially not to raise other parents’ expectations. But I don’t think the controversy should be allowed to rest so easily. The King family’s experience raised serious questions about the practice of medicine in the UK and the attitudes of the professionals to their patients. And these latest research findings on proton therapy mean that it still does.

When Brett King presented his arguments, he did so not just with understandable emotion, but with enviable lucidity. He patently understood what he was talking about. This treatment was there; he wanted to give it a go, and he was prepared to raise the funds to pay for it. To the medics, he may well have come across as difficult, and there were those who genuinely felt that he was acting against the best interests of his son. In that case, the arguments should have gone to court – as they had done with eight-year-old Neon Roberts and his contested cancer treatment half a year before. That the Kings are Jehovah’s Witnesses may also have cued particular caution.

However, what many, especially in the medical establishment, seem reluctant to recognise is that change is afoot in relations between the professional elite and the rest – and not only because the so-called “age of deference” is dead.

Increasingly, it seems, we lay people are invited to make choices, only to be censured, or worse, for making the “wrong” one. Lawyers, for instance, will repeatedly tell you that they offer only advice; it is up to us to act on it, or not. So it is, increasingly, in the NHS.

In theory, you can choose your GP, your hospital, your consultant – and, within reason, your treatment. In practice, it is more complicated. You may live too far away, the professionals may try to protect their patch, and the actual consultant is not there.

In the crucial matter of information, however, things have been evening up. The internet-nerd who turns up at the GP surgery convinced he is mortally ill may be a time-consuming nuisance, but such self-interested diligence can also help to point a time-strapped GP in the right direction. Not all are hypochondriacs. Patients may have more time and motive to research new treatments than their doctor. We old-fashioned scribes may have misgivings about the rise of citizen-journalism. But not all challenges to professional expertise are ignorant – or wrong.

In the case of Ashya King, everyone behaved questionably, even as they genuinely believed they were acting in the child’s very best interests.

But the days when the professionals – for all their years of training – had the field to themselves are gone. In medicine, we lay people are getting used to that. Are they?

In the crucial matter of information, however, things have been evening up. The internet-nerd who turns up at the GP surgery convinced he is mortally ill may be a time-consuming nuisance, but such self-interested diligence can also help to point a time-strapped GP in the right direction. Not all are hypochondriacs. Patients may have more time and motive to research new treatments than their doctor. We old-fashioned scribes may have misgivings about the rise of citizen-journalism. But not all challenges to professional expertise are ignorant – or wrong.

In the case of Ashya King, everyone behaved questionably, even as they genuinely believed they were acting in the child’s very best interests.

But the days when the professionals – for all their years of training – had the field to themselves are gone. In medicine, we lay people are getting used to that. Are they?

Friday, 29 May 2015

Shoddy Science - Study showing that chocolate can help with weight loss was a trick

Kashmira Gander in The Independent

A journalist seeking to lay bare how the research behind fad diets can be “meaningless” and based on “terrible science”, has revealed how he tricked international media into believing that chocolate can aid weightloss.

Posing as Johannes Bohannon, Ph.D, the research director of the fabricated Institute of Diet and Health, biologist and science journalist John Bohannon ran what he called a “fairly typical study” used in the field of diet research.

German broadcast journalists Peter Onneken and Diana Löbl asked Bohannon to conduct a clinical trial into the effects of dark chocolate, as part of a documentary exposing how simple it is for bad science to make headlines.

“It was terrible science. The results are meaningless, and the health claims that the media blasted out to millions of people around the world are utterly unfounded,” Bohannon wrote of his in an article for io9.com.

To collate their data, the team asked 5 men and 11 women aged between 19 to 67 to follow either a low-carbohydrate diet, or the same diet but with an added 1.5oz of dark chocolate. Meanwhile, a control group were asked to eat as normal.

While the data showed that the group which ate a low-carb diet while indulging in dark chocolate lost weight 10 per cent faster and had better cholesterol readings, Bohannon stressed that the study was set up for failure.

“Here’s a dirty little science secret: If you measure a large number of things about a small number of people, you are almost guaranteed to get a “statistically significant” result.”Bohannon explained that thanks to a method known as "p-hacking", the study could have just as likely shown that chocolate helped sleep or lowered blood pressure as the threshold for data being classed as "significant" is just 0.05 per cent.

THE STUDY COULD HAVE JUST AS LIKELY SHOWN A POSITIVE EFFECT ON BLOOD PRESSURE THAN WEIGHT LOSS, SAYS BOHANNON (PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES)

THE STUDY COULD HAVE JUST AS LIKELY SHOWN A POSITIVE EFFECT ON BLOOD PRESSURE THAN WEIGHT LOSS, SAYS BOHANNON (PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES)

After a journal was duped into accepting the shoddy study for money, Bohannon and his colleagues then put together a press release which would be irresistible to journalists and editors looking for a story.

The research was splashed across newspapers and websites across 20 countries in half a dozen languages, seemingly proving how easily dodgy science can circulate across the world’s media.

However, some have questioned the ethic behind the study, with one commenter writing below the piece:

"Going out of their way to court media coverage (that was going to repeat the story but never, ever follow up on the hoax once it was revealed — and this is a hoax) was ethically problematic,” one commenter said.

"If you want to uncover the shady workings, that didn’t really help. It seems like only the people who were already aware of the problems are going to be reached by this reveal."

The stunt came after Bohannon exposed how “open access”science journals were willing to publish deeply flawed research claiming that a drug had anti-cancer properties.

In the investigation for the prestigious journal Science, he revealed the dangers of abandoning the peer-review process expected in science publishing.

Friday, 2 January 2015

We can’t control how we’ll die. The limits of individual responsibility

It’s important to live healthily, but scientists also tell us that the majority of cancers are down to chance – a good reminder of the limits of individual responsibility

Our terror of death (happy new year, by the way) surely has much to do with a fear that it is out of our control. The lifetime risk of dying in a road accident is disturbingly high – one in 240 – and yet the freakishly small chance of dying in a plane accident generally provokes far more fear. We dread a final few moments in which we are powerless to do anything except wait for oblivion. So perhaps the news that most cancers are the product of bad luck – rather than, say, our diet or lifestyles – is scant reassurance. Most cancers are a random lightning bolt, not something we can avoid by keeping away from tobacco or excessive booze, or by going for regular morning runs. That’s something we have to live with.

But perhaps the news should be of comfort. It is, of course, crucial to promote healthy lifestyles. Regular exercise, a good diet and the avoidance of excess does save lives. Yet the cult of individualism fuels the idea that we are invariably personally responsible for the situation we are in: whether that be poverty, unemployment or ill health. Cancer is more individualised than most diseases: all that talk of “losing” or “winning” battles. A far wiser approach was summed up by DJ Danny Baker after his own diagnosis. He said he was “just the battlefield, science is doing the fighting and of course the wonderful docs and nurses of the brilliant NHS”. The cancer patient, in other words, was practically a bystander in a collective effort.

One of the heroes of 2014 was Stephen Sutton because of his infectious optimism and cheerfulness in the face of cancer. But his battle was about not letting cancer consume his final few months on earth, rather than a superhuman quest to miraculously defeat the disease himself. What struck me about Stephen was that a situation that seemed nightmarish to most of us became an opportunity for him to take control of his life. It is what struck me, too, about Gordon Aikman, a 29-year-old Scot with a terminal diagnosis of motor neurone disease. There is no right way to die, but he has learned how to live.

So that’s why I have some sympathy with Richard Smith, a doctor who once edited the British Medical Journal. He has upset many by suggesting we are “wasting billions trying to cure cancer”, when it is the “best” way to go. I certainly would not advocate cutting back on cancer research, quite the opposite – even if other fatal diseases don’t receive the same amount of attention – and cancer can be a horrible way to die. But his point was that it provided an opportunity to make peace, to reflect on life, to do all the things you always wanted to do – to finally have control over your own life. Other ways of dying simply do not provide that option, either because they are so sudden or because of the form they take.

We have less of a say over how and when we die than we thought. That may be a cause for anxiety: it may actually frighten us more. I think it’s liberating. If only we learned to live like many of those – like Stephen or Gordon – facing death, taking control of their lives, we would be so much happier than we are.

Wednesday, 29 October 2014

Sex with more than 20 women reduces risk of prostate cancer, according to study

Antonia Molloy in The Independent

There’s good news for the Casanovas of the world – sleeping with numerous women could help to protect men from prostate cancer, according to a new study.

Researchers at the University of Montreal and INRS-Institut Armand-Frappier found that men who had slept with more than 20 women during their lifetime were 28 per cent less likely to develop the disease.

They were also 19 per cent less likely to develop an aggressive type of cancer, compared to those who had had only one female sexual partner.

However, the same did not apply to gay men, according to the Canadian scientists. They found that having more than 20 male partners doubled the risk of prostate cancer and made an aggressive cancer five times more likely. Sleeping with one male partner did not affect the risk.

Meanwhile, men who were virgins were almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer as those who were sexually experienced.

The findings are from the Prostate Cancer & Environment Study in which 3,208 men answered questions about their lifestyle and sex lives.

Of these men, 1,590 were diagnosed with prostate cancer between September 2005 and August 2009, while 1,618 men were part of the control group.

Overall, men with prostate cancer were twice as likely as others to have a relative with cancer, but the study also found a possible link with their number of sexual partners.

Lead researcher Professor Marie-Elise Parent, from the University of Montreal, said: "It is possible that having many female sexual partners results in a higher frequency of ejaculations, whose protective effect against prostate cancer has been previously observed in cohort studies."

According to one theory, large numbers of ejaculations may reduce the concentration of cancer-causing substances in prostatic fluid, a constituent of semen.

They may also lead to fewer crystal-like structures in the prostate that have been associated with prostate cancer.

Suggesting why the same did not apply to male partners Professor Parent admitted she could only provide "highly speculative" explanations.

One explanation she said "could be that anal intercourse produces a physical trauma to the prostate".

The age at which men first had sexual intercourse, and the number of times they had been infected by a sexually transmitted disease, had no bearing on prostate cancer risk.

A total of 12 per cent of the group reported having had at least one sexually transmitted infection (STI) in their lifetime.

Professor Parent added: "We were fortunate to have participants from Montreal who were comfortable talking about their sexuality, no matter what sexual experiences they have had, and this openness would probably not have been the same 20 or 30 years ago.

"Indeed, thanks to them, we now know that the number and type of partners must be taken into account to better understand the causes of prostate cancer."

On the question of whether promiscuity might now be recommended in health advice to men, she said: "We're not there yet."

The research is published in the journal Cancer Epidemiology.

Friday, 2 May 2014

Big Pharma, my cancer patient and me

My patient was refused compassionate access to a cheap chemotherapy. Why? Because pharmaceutical companies are often guilty of selling an ethically murky kind of hope

After failing two types of chemotherapy for advanced cancer, my patient knew that her lease on life was short, but a cherished family event stood in the way. "My son is going to propose at the Christmas table, I just want to make it there." Her son has been her anchor throughout her challenge; I could see why his engagement mattered so much. But Christmas was still some months away, and I feared the feat will be difficult.

"I am not afraid to die but I just want to know that I gave it my all." This is an all too frequent exchange, unfailingly poignant, often heart-wrenching. An entirely reasonable answer would be to gently reiterate the lack of meaningful chemotherapy, broach the benefit of good palliative care, and allow for regret at both our ends. Contrary to popular belief that mythologizes every patient raging against cancer to the very end, for many this discussion eases the burden of expectation and allows for a peaceful end.

But this relatively young mother was simply not ready yet. "I would happily die right after he proposed" she smiled, reminding me that her goalposts had never changed. When a patient like that looks you in the eye, it isn’t easy to separate foreboding statistics and human longing into two neat piles and deny hope.

My head said that another chemotherapy drug wouldn't make a significant survival difference. But my heart urged me to try, if not to boost survival, then merely to reassure her that she gave it her best shot. Put simply, we both knew that the gesture will be more therapeutic than the drug itself, hardly a rare observation in medicine.

I wrote to a large pharmaceutical company for compassionate access to a common chemotherapy that’s not government subsidised for her precise type of cancer (most likely because patients typically don’t live long enough to need it). It is a relatively old and cheap drug, importantly with manageable toxicity, and I requested a month’s supply to gauge response. I added that the patient does not expect recurrent funding in case she responds to the drug, addressing a legitimate concern. In a world where we frequently push the boundaries or prescribe chemotherapy in more questionable circumstances, I feel comfortable that what I am really doing is asking the company to be my partner in nurturing hope. Which is after all what every pharmaceutical representative has told me for as long as I have known.

So I simply don’t believe it when my request is declined. Thinking this to be a mistake, I protest further up the chain, pointing out to a senior executive that only recently the company had offered me conference sponsorship worth thousands more than the small cost of the chemotherapy. The apologies come fast, but the explanations are notably absent.

My naive puzzlement slowly turns into the realisation that almost every instance where a company has facilitated compassionate access to a product, it has been as a form of marketing as a means of gaining lucrative, government-subsidised listing. In the era of astonishingly expensive blockbuster drugs, government subsidisation is the holy grail of big pharma. The cost of treating a few hundred or even a few thousand patients for free (and in the process, securing the backing of doctors), is negligible when the ultimate prize is full government subsidy. Indeed, individuals and organisations including the UK’s NICE and Australia’s PBS are now questioning the feasibility of subsidising drugs that can cost as much as AU$200,000 a year for ambiguous benefit.

Compassionate access schemes for these incredibly expensive drugs might facilitate access for selected patients but they are not truly compassionate in the way that the average person understands. Pharmaceutical companies sell an ethically murky kind of hope than what doctors and their patients might understand. The benefit to the company must ultimately outweigh the benefit to the individual patient. If subsidy looks unlikely, access schemes are retired, sometimes abruptly. When a commonplace drug is neither vying for market recognition nor fighting for subsidisation, there is no incentive to provide it to a patient like mine, whose story would anyway never be the stuff of headlines.

You might ask the obvious question as to why it would take so long for an oncologist to figure out that a pharmaceutical company is not a charity. The common argument is that companies must necessarily recoup the cost of drug development, as only a small minority succeed in the marketplace.

But for every dollar spent on research, nearly twice is spent on lobbying and marketing – and it is also this expense that companies want to recover. From the time they are students, doctors are exposed to relentless advertising that big pharma is their companion in healthcare. The glory days of advertising saw doctors offered egregious forms of largesse, from conferences hosted in ancient castles and on cruises to lavish dining and entertainment. Then there were the rivers of pens post-it notes, stress balls and cute toys to influence prescribing. Regulation is much tighter today, but there is still plenty of money in sponsorships, paid speaking tours, adding one’s credible name to journal articles, and just promoting a drug to one’s peers, especially if you are anointed a key opinion leader.