'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 17 September 2023

Saturday, 16 September 2023

Wednesday, 13 September 2023

Monday, 11 September 2023

Sunday, 10 September 2023

A Level Economics: What is a Failed State?

On YouTube, there are numerous videos on ‘failed states’. Those posted by certain American news outlets almost always describe Russia as a failed or failing state. Similarly, videos produced by Indian media outlets often refer to Pakistan as a failed/failing state. Then there are also some videos produced in China which ‘predict’ the collapse of the American state structure, and many American videos that speak of ‘China’s coming collapse’.

So what is a failed state?

There are various theories about what constitutes state failure, but most political scientists and economists agree on two major symptoms of this failure. The first is when the state loses its ability to establish authority over its territory and citizens, and is unable to protect the country’s sovereignty. Secondly, state failure also constitutes the state’s inability to provide basic necessities to its citizens and when a country’s governing institutions become ineffective.

However, according to foreign policy experts such as the Norwegian Morten Bøås, the application of the term ‘failed state’ is largely political in nature. A country threatened by another country whose state is facing a crisis, often labels it as a failed or failing state. This is why to the US, at the moment, Russia is a ‘failing state’ and to India, so is Pakistan.

Recently, Chinese propaganda has claimed that the US is on the brink of state failure, especially after the ‘backsliding’ that American democracy witnessed during the Trump presidency. It’s politics.

The definition of what constitutes a ‘failed’ or ‘failing’ state may be determined by geopolitical interests, but the internal role of extractive and exclusivist institutions cannot be ignored

But does this mean that there are no failed states at all? There are. Most political scientists agree that Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia, Syria, DR Congo and Sudan are failed states because state authority in these countries has almost completely collapsed. Outside the confines of areas in which the state does have some authority left, ‘non-state actors’ hold sway. Poverty, political chaos and violence are rampant. There is no presence of a cohesive state here.

Even though one may agree with men such as Bøås that ‘failed state’ is a political term applied for propaganda purposes to justify external armed intervention or to impose economic sanctions, this does not mean that, apart from the more blatant examples of failed states, other countries are entirely safe from becoming another Afghanistan or Somalia.

Most states, even in developed countries, often exhibit some symptoms of state failure. But the symptoms are particularly intense in developing countries, where there is a greater chance of the state failing.

In Pakistan, when Islamist militants had occupied vast swaths of land in the early 2010s, and the state seemed ill-equipped or even reluctant to reestablish its writ in these regions, many voices inside and outside the country warned that Pakistan was heading towards state failure.

The warning was not exaggerated. However, the state too was conscious of this. It finally responded by conducting an unprecedented military operation. Between 2014 and 2017, it was able to oust the militants from areas where they had established parallel governing systems, mostly based on outright terror.

But military action alone against forces challenging the writ of the state is not enough. In the book Why Nations Fail, the economists James A. Robinson and Daron Acemoglu write that nations fail not because they lack abundant natural resources or are located in volatile regions. One of the most prominent reasons that states fail is because of ‘extractive’ political and economic institutions.

Nation states with inclusive institutions prosper because these institutions do not restrict the economic and political participation of all citizens. It does not matter what race or religion a citizen belongs to, they are encouraged to bolster the country’s, and their own, economic ambitions.

Extractive institutions go the other way. Economic and political elites accumulate power and wealth for themselves from those who can’t find a voice or place in the extractive institutions. Pakistan is a parliamentary democracy. But this democracy is largely extractive and exclusivist. Its exclusivist nature is deeper than just ‘elite capture’. This is so because the non-Sunni and non-Muslim communities too are kept at an arm’s length, because they do not adhere to the definition of Islam defined by the Constitution. Some are even outrightly repressed.

A powerful state institution in Pakistan, the military, sees itself above this nature of exclusivity. Yet, from the 1980s onwards, it was the military that further strengthened extractive and exclusivist policies and even used exclusivist forces to meet its own political ambitions. The parliament and a politicised military have both contributed in severely limiting the participation of the diverse talent required to construct robust economic and political institutions.

The continuing extractive policies have now instigated a clash within the extractive elites, both civilian and military. The extractive elites benefitted the most through exclusivist policies. On the other hand, those who are kept out because of their faith, sect, ethnicity or class have been severely marginalised and are just mere spectators of an ongoing tussle for power between the two factions of the extractive forces.

The ‘anti-military’ riots on May 9 and 10 were an example of one extractive group trying to push back the other. So, the crisis of the state that Pakistan is facing today is also about a crisis within elite groups. A new election alone won’t resolve the crisis. Pakistan’s democracy is still navigated by an exclusivist constitution, which can actually deepen the crisis.

I believe, alarmed by such a possibility, the military is contemplating a Hobbesian route. In his highly influential book The Leviathan, the 17th century British philosopher Thomas Hobbes posited that, in exchange for getting protection from violence, war, chaos, poverty and crime, the citizens are required to delegate a large degree of power to a sovereign state.

The exchange may also require the citizens to relinquish certain rights, so that the sovereign can work freely to guarantee the economic and political security of the citizens without any hindrance.

Indeed, this is clearly an authoritarian view, but Hobbes does warn the sovereign that the failure to do so is likely to cause state failure. On May 9 and 10, the extractive faction that the military was once the architect of, tried to usurp power by rationalising its actions as ‘pro-democracy’ and supported by ‘civil society’.

I believe that, even if and when electoral democracy returns, the Hobbesian route will continue to be taken, because the military is now convinced that anything else is bound to put the state on the brink of failure.

Wednesday, 6 September 2023

Friday, 1 September 2023

How paranoid nationalism corrupts

From The Economist

People seek strength and solace in their tribe, their faith or their nation. And you can see why. If they feel empathy for their fellow citizens, they are more likely to pull together for the common good. In the 19th and 20th centuries love of country spurred people to seek their freedom from imperial capitals in distant countries. Today Ukrainians are making heroic sacrifices to defend their homeland against Russian invaders.

Unfortunately, the love of “us” has an ugly cousin: the fear and suspicion of “them”, a paranoid nationalism that works against tolerant values such as an openness to unfamiliar people and new ideas. What is more, cynical politicians have come to understand that they can exploit this sort of nationalism, by whipping up mistrust and hatred and harnessing them to benefit themselves and their cronies.

The post-war order of open trade and universal values is strained by the rivalry of America and China. Ordinary people feel threatened by forces beyond their control, from hunger and poverty to climate change and violence. Using paranoid nationalism, parasitic politicians prey on their citizens’ fears and degrade the global order, all in the pursuit of their own power.

As our Briefing describes, paranoid nationalism works by a mix of exaggeration and lies. Vladimir Putin claims that Ukraine is a nato puppet, whose Nazi cliques threaten Russia; India’s ruling party warns that Muslims are waging a “love jihad” to seduce Hindu maidens; Tunisia’s president decries a black African “plot” to replace his country’s Arab majority. Preachers of paranoid nationalism harm the targets of their rhetoric, obviously, but their real intention is to hoodwink their own followers. By inflaming nationalist fervour, self-serving leaders can more easily win power and, once in office, they can distract public attention from their abuses by calling out the supposed enemies who would otherwise keep them in check.

Daniel Ortega, the president of Nicaragua, shows how effective this can be. Since he returned to power in 2006, he has demonised the United States and branded his opponents “agents of the Yankee empire”. He controls the media and has put his family in positions of influence. After mass protests erupted in 2018 at the regime’s graft and brutality, the Ortegas called the protesters “vampires” and locked them up. On August 23rd they banned the Jesuits, a Catholic order that has worked in Nicaragua since before it was a country, on the pretext that a Jesuit university was a “centre of terrorism”.

Rabble-rousing often leads to robbery. Like the Ortegas, some nationalist leaders seek to capture the state by stuffing it with their cronies or ethnic kin. The use of this technique under Jacob Zuma, a former president of South Africa, is one reason why the national power company is too riddled with corruption to keep the lights on. Our statistical analysis suggests that governments have grown more nationalistic since 2012, and that the more nationalistic they are, the more corrupt they tend to be.

But the more important role of paranoid nationalism is as a tool to dismantle the checks and balances that underpin good governance: a free press, independent courts, ngos and a loyal opposition. Leaders do not say: “I want to purge the electoral commission so I can block my political opponents.” They say: “The commissioners are traitors!” They do not admit that they want to suppress ngos to evade scrutiny. They pass laws defining as “foreign agents” any organisation that receives foreign funds or even advice, and impose draconian controls on such bodies or simply ban them. They do not shut down the press, they own it. By one estimate, at least 50 countries have curbed civil society in recent years.

An example is the president of Tunisia, Kais Saied. Before he blamed black people for his country’s problems, he was unpopular because of his dismal handling of the economy. Now Tunisians are cheering his bold stand against a tiny, transient minority. Meanwhile Mr Saied has gutted the judiciary and closed the anti-corruption commission, and graft has grown worse.

Abuses are easier when institutions are weak: the despots of Nicaragua, Iran or Zimbabwe are far less constrained than the leaders of say, Hungary or Israel. But in all these countries (and many more), the men in power have invented or exaggerated threats to the nation as a pretext to weaken the courts, the press or the opposition. And this has either prolonged a corrupt administration or made it worse.

Paranoid nationalism is part of a backlash against good governance. The end of the cold war led to a blossoming of democracy around the world. Country after country introduced free elections and limits on executive power. Many power- and plunder-hungry politicians chafed at this. Amid the general disillusion that followed the financial crisis of 2007-09, they saw an opportunity to take back control. Paranoid nationalism gave them a tool to dismantle some of those pesky checks and balances.

Because these restraints often came with Western encouragement, if not Western funding, leaders have found it easier to depict the champions of good government as being foreign stooges. In countries that have endured colonial rule—or interference by the United States, as have many in Latin America—the message finds a ready audience. If a leader can create a climate of such deep suspicion that loyalty comes before truth, then every critic can be branded a traitor.

First resort of the scoundrel

Paranoid nationalism is not about to disappear. Leaders are learning from each other. They are also freer to act than they were even a decade ago. Not only has the West lost faith in its programme of spreading democracy and good governance, but China—a paranoid nationalist that is inclined to spot slights and threats around every corner—is promoting the idea that universal values of tolerance and good governance are a racist form of imperialism. It prefers non-interference from abroad and zero-criticism at home. If only they could see through the lies behind paranoid nationalism, ordinary people would realise how wrong China’s campaign is. There is nothing racist or disloyal about wishing for a better life.

Sunday, 27 August 2023

Friday, 25 August 2023

Tuesday, 22 August 2023

A level Economics: India's Economic Data could be fiction

T C A Sharad Raghavan in The Print

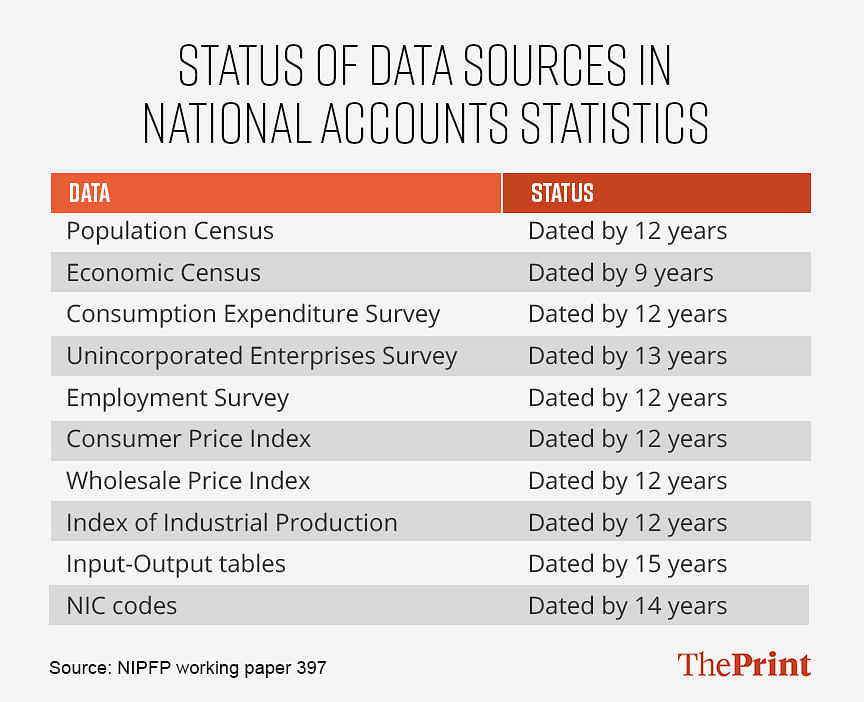

The next time somebody, even the Prime Minister, boasts about India being the fastest-growing economy or that it is the fifth largest in the world, ask them to prove it. Even Modi will not be able to. The reams of government data that will be thrown at you will almost all be incorrect, and the analysis done on them will be guesswork at best. The reason for this is not some convoluted statistical reasoning. It’s much simpler: the data is outdated and largely meaningless. The most recent actual data for the Indian economy we have is about 12 years old.

Amrit Kaal may be the target, but we don’t even know our starting point.

The old…

Let’s take something as conceptually simple as per capita gross domestic product (GDP)—basically the total output of the country divided by the population. It serves as a broad proxy to denote the wealth of an average Indian. Should be simple enough to calculate, right? Let’s start with the numerator, which is the GDP figure.

The agriculture sector probably has the most up-to-date data when it comes to the overall GDP measure, and even that comes with a delay of about two years. The Directorate of Economics and Statistics in the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare compiles the data on India’s agriculture output for any given year, and releases four advance estimates, before the final figures come out about two years after the collection.

Such a ‘short’ delay of just two years might have been okay if agriculture formed a larger part of our GDP. But with a share of less than 20 per cent, accuracy of agricultural data, while important, doesn’t materially improve the quality of the overall GDP number.

From here, it just becomes worse.

The manufacturing sector is divided into the organised sector and the unorganised sector. Data for the organised sector used to come from the Annual Survey of Industries—but with a lag. Now it comes from the much more up-to-date MCA-21 database compiled by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs. That’s not the problem here. The unorganised sector is.

The unorganised or informal sector, by definition, is difficult to quantify because there are no formal metrics through which such an audit can take place. If you could effectively measure it, it would not be ‘unorganised’ or ‘informal’. Rather, it is ‘unorganised’ because you can’t measure it.

Policymakers have gotten around this problem by periodically doing a nation-wide survey. Using the findings of the survey of the informal sector, the statisticians in the government then arrive at a ratio that can neatly be multiplied by the size of the formal sector, to arrive at an approximation of the size of the informal economy.

So, let’s say the formal sector is Rs 100 in size, and the ratio they have arrived at is 1.25. The informal sector would then be estimated at Rs 125 (Rs 100 x 1.25), which then gives you the total economic output of the sectors being measured—Rs 225 (Rs 100 + 125).

Ideally, this would work well. However, at a time when the latest survey of the informal sector—the Unincorporated Enterprises Survey—is from about 13 years ago, well before demonetisation, GST, and Covid, we don’t really know what shape the informal sector is in right now.

Then we come to the services. Trade, hotels, restaurants, real estate, all have significant contributions to GDP and sizeable informal segments, all of which are based on surveys conducted in 2011-12 or thereabouts.

Just think about the sea change the Indian economy has witnessed since 2011—both the positive and the negative. Inequality has widened, but access to basic essentials has improved. Demonetisation wiped out 86 per cent of the cash in the system overnight. The indirect tax system was overhauled with GST. A pandemic disrupted the economy like never before.

And then there are the myriad smaller changes that over time become big. The movie theatre industry has changed so dramatically. An entire generation of entrepreneurs are minting money by creating two-minute videos, forget any sort of asset creation. None of these or the million other changes to the Indian economy over the last decade are being captured in the data.

So that’s the numerator of the per capita GDP formula—almost every aspect of it is outdated. The denominator is the population of India, measured by the Census of India. When was the latest one? You guessed it, 12 years ago!

…and the uncaptured

So, if the GDP number as well as the population size are both more than a decade old, then when somebody talks about the size of the economy or per capita income, what are they talking about? It’s not the present, for sure.

Our data issues don’t end there. The other big number on everybody’s mind is inflation. As this analysis shows, the Consumer Price Index—which is what the Reserve Bank of India uses to measure inflation—falls woefully short of truly measuring the impact of rising prices on the people. The weightage for food is too high, while that of fuel and services such as health, education, and transport and communication are too low.

So, you have a situation where the overall inflation rate gets affected by a change in the price of wheat, even though 80 crore Indians currently get it for free. Or you have a situation where fuel prices shoot up in response to global oil prices, but the overall inflation rate barely registers it. And, while the middle class increasingly prefers private hospitals and private schools (don’t forget tuition classes), this increased spending on health and education is not getting captured.

In fact, with the latest usable Household Consumption Expenditure Survey being only available for the year 2011-12, we actually have only a vague idea about how people are spending their money and how much they are earning.

It’s fine for developed countries like the US to not update their CPI for around 40 years—though even there it might be time for a revision—because the rate of change of these basic economic indicators is much lower there than in an emerging economy like India. Here, a decade is a long time, and a lot can change during it.

It’s not just these, though. Several lesser-known but key surveys that underpin the very basic estimates we have of the economy haven’t been updated in years. The Economic Census is nine years old, the employment survey is 12 years old, as is the base year of the Index of Industrial Production. The input-output tables, critical to measuring the relationship between the production and use of various items in the economy, are 15 years too old.

The government can say all it wants about Amrit Kaal arriving and India becoming a developed nation by 2047, but if it wants to seriously achieve this trajectory, it is first going to have to establish where we stand now.

Thursday, 17 August 2023

What India’s foreign-news coverage says about its world-view

When Narendra Modi visited Washington in June, Indian cable news channels spent days discussing their country’s foreign-policy priorities and influence. This represents a significant change. The most popular shows, which consist of a studio host and supporters of the Hindu-nationalist prime minister jointly browbeating his critics, used to be devoted to domestic issues. Yet in recent years they have made room for foreign-policy discussion, too.

Much of the credit for expanding Indian media’s horizons goes to Mr Modi and his foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, who have skilfully linked foreign and domestic interests. What happens in the world outside, they explain, affects India’s future as a rising power. Mr Modi has also given the channels a lot to discuss; a visit to France and the United Arab Emirates in July was his 72nd foreign outing. India’s presidency of the G20 has brought the world even closer. Meetings have been scheduled in over 30 cities, all of which are now festooned with G20 paraphernalia.

Yet it is hard to detect much deep interest in, or knowledge of, the world in these developments. There are probably fewer Indian foreign correspondents today than two decades ago, notes Sanjaya Baru, a former editor of the Business Standard, a broadsheet. The new media focus on India’s role in the world tends to be hyperpartisan, nationalistic and often stunningly ill-informed.

This represents a business opportunity that Subhash Chandra, a media magnate, has seized on. In 2016 he launched wion, or “World Is One News”, to cover the world from an Indian perspective. It was such a hit that its prime-time host, Palki Sharma, was poached by a rival network to start a similar show.

What is the Indian perspective? Watch Ms Sharma and a message emerges: everywhere else is terrible. Both on wion and at her new home, Network18, Ms Sharma relentlessly bashes China and Pakistan. Given India’s history of conflict with the two countries, that is hardly surprising. Yet she also castigates the West, with which India has cordial relations. Europe is taunted as weak, irrelevant, dependent on America and suffering from a “colonial mindset”. America is a violent, racist, dysfunctional place, an ageing and irresponsible imperial power.

This is not an expression of the confident new India Mr Modi claims to represent. Mindful of the criticism India often draws, especially for Mr Modi’s Muslim-bashing and creeping authoritarianism, Ms Sharma and other pro-Modi pundits insist that India’s behaviour and its problems are no worse than any other country’s. A report on the recent riots in France on Ms Sharma’s show included a claim that the French interior ministry was intending to suspend the internet in an attempt to curb violence. “And thank God it’s in Europe! If it was elsewhere it would have been a human-rights violation,” she sneered. In fact, India leads the world in shutting down the internet for security and other reasons. The French interior ministry had anyway denied the claim a day before the show aired.

Bridling at lectures by hypocritical foreign powers is a longstanding feature of Indian diplomacy. Yet the new foreign news coverage’s hyper-defensive championing of Mr Modi, and its contrast with the self-confident new India the prime minister describes, are new and striking. Such coverage has two aims, says Manisha Pande of Newslaundry, a media-watching website: to position Mr Modi as a global leader who has put India on the map, and to promote the theory that there is a global conspiracy to keep India down. “Coverage is driven by the fact that most tv news anchors are propagandists for the current government.”

This may be fuelling suspicion of the outside world, especially the West. In a recent survey by Morning Consult, Indians identified China as their country’s biggest military threat. America was next on the list. A survey by the Pew Research Centre found confidence in the American president at its highest level since the Obama years. But negative views were also at their highest since Pew started asking the question.

That is at odds with Mr Modi’s aim to deepen ties with the West. And nationalists are seldom able to control the forces they unleash. China has recently sought to tamp down its aggressive “wolf-warrior diplomacy” rhetoric. But its social media remain mired in nationalism. Mr Modi, a vigorous champion for India abroad, should take note. By letting his propagandists drum up hostility to the world, he is laying a trap for himself.

A level Economics: Can India Inc extricate itself from China?

The Economist

China and India are not on the friendliest of terms. In 2020 their soldiers clashed along their disputed border in the deadliest confrontation between the two since 1967—then clashed again in 2021 and 2022. That has made trade between the Asian giants a tense affair. Tense but, especially for India, still indispensable. Indian consumers rely on cheap Chinese goods, and Indian companies rely on cheap Chinese inputs, particularly in industries of the future. Whereas India sells China the products of the old economy—crustaceans, cotton, granite, diamonds, petrol—China sends India memory chips, integrated circuits and pharmaceutical ingredients. As a result, trade is becoming ever more lopsided. Of the $117bn in goods that flowed between the two countries in 2022, 87% came from China (see chart).

India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, wants to reduce this Sino-dependence. One reason is strategic—relying on a mercurial adversary for critical imports carries risks. Another is commercial—Mr Modi is trying to replicate China’s nationalistic, export-oriented growth model, which means seizing some business from China. In recent months his government’s efforts to decouple parts of the Indian economy from its larger neighbour’s have intensified. On August 3rd India announced new licensing restrictions for imported laptops and personal computers—devices that come primarily from China. A week later it was reported that similar measures were being considered for cameras and printers.

Officially, India is open to Chinese business, as long as this conforms with Indian laws. In practice, India’s government uses a number of tools to make Chinese firms’ life in India difficult or impossible. The bluntest of these is outright prohibitions on Chinese products, often on grounds related to national security. In the aftermath of the border hostilities in 2020, for example, the government banned 118 Chinese apps, including TikTok (a short-video sensation), WeChat (a super-app), Shein (a fast-fashion retailer) and just about any other service that captured data about Indian users. Hundreds more apps were banned for similar reasons throughout 2022 and this year. Makers of telecoms gear, such as Huawei and zte, have received the same treatment, out of fear that their hardware could let Chinese spooks eavesdrop on Indian citizens.

Tariffs are another popular tactic. In 2018, in an effort to reverse the demise of Indian mobile-phone assembly at the hands of Chinese rivals, the government imposed a 20% levy on imported devices. In 2020 it tripled tariffs on toy imports, most of which come from China, to 60% then, at the start of this year, raised them to 70%. India’s toy imports have since declined by three-quarters.

Sometimes the Indian government eschews official actions such as bans and tariffs in favour of more subtle ones. A common tactic is to introduce bureaucratic friction. India’s red tape makes it easy for officials to find fault with disfavoured businesses. Non-compliance with tax rules, so impenetrable that it is almost impossible to abide by them all, are a favourite accusation. Two smartphone makers, Xiaomi and bbk Electronics (which owns three popular brands, Oppo/OnePlus, Realme and Vivo), are under investigation for allegedly shortchanging the Indian taxman a combined $1.1bn. On August 2nd news outlets cited anonymous government officials saying that the Indian arm of byd, a Chinese carmaker, was under investigation over allegations that it paid $9m less than it owed in tariffs for parts imported from abroad. mg Motor, a subsidiary of saic, another Chinese car firm, faces investment restrictions and a tax probe.

A convoluted licensing regime gives Indian authorities more ways to stymie Chinese business. In April 2020 India declared that investments from countries sharing a border with it must receive special approvals. No specific neighbour was named but the target was clearly China. Since then India has approved less than a quarter of the 435 applications for foreign direct investment from the country. According to Business Today, a local outlet, only three received the thumbs-up in India’s last fiscal year, which ended in March. Last month reports surfaced that a proposed joint venture between byd and Megha Engineering, an Indian industrial firm, to build electric vehicles and batteries failed to win approval over security reasons.

Luxshare, a big Chinese manufacturer of devices for, among others, Apple, has yet to open a factory in Tamil Nadu, despite signing an agreement with the state in 2021. The reason for the delay is believed to be an unspoken blanket ban from the central government in Delhi on new facilities owned by Chinese companies. In early August the often slow-moving Indian parliament whisked through a new law easing the approval process for new lithium mines after a potentially large deposit of the metal, used in batteries, was unearthed earlier this year. Miners are welcome to submit applications, but Chinese bidders are expected to be viewed unfavourably.

In parallel to its blocking efforts, India is using policy to dislodge China as a leader in various markets. India’s $33bn programme of “production-linked incentives” (cash payments tied to sales, investment and output) has identified 14 areas of interest, many of which are currently dominated by Chinese companies.

One example is pharmaceutical ingredients, which Indian drugmakers have for years mostly procured from China. In February the Indian government started doling out handouts worth $2bn over six years to companies that agree to manufacture 41 of these substances domestically. Big pharmaceutical firms such as Aurobindo, Biocon, Dr Reddy’s and Strides are participating. Another is electronics. Contract manufacturers of Apple’s iPhones, such as Foxconn and Pegatron of Taiwan and Tata, an Indian conglomerate, are allowed to purchase Chinese-made components for assembly in India provided they make efforts to nurture local suppliers, too. A similar arrangement has apparently been offered to Tesla, which is looking for new locations to make its electric cars.

Some Chinese firms, tired of jumping through all these hoops, are calling it quits. In July 2022, after two years of efforts that included a promise to invest $1bn in India, Great Wall Motors closed its Indian carmaking operation, unable to secure local approvals. Others are trying to adapt. Xiaomi has said it will localise all its production and expand exports from India which, so far, go only to neighbouring countries, to Western markets. Shein will re-enter the Indian market through a joint venture with Reliance, India’s most valuable listed company, renowned for its ability to navigate Indian bureaucracy and politics. zte is reportedly attempting to arrange a licensing deal with a domestic manufacturer to make its networking equipment. So far it has found no takers. Given India’s growing suspicions of China, it may be a while before it does.

Wednesday, 16 August 2023

Monday, 14 August 2023

A level Economics: Are Universal Values a form of Imperialism?

Prosperity certainly rose. In the three decades to 2019, global output increased more than fourfold. Roughly 70% of the 2bn people living in extreme poverty escaped it. But individual freedom and tolerance evolved differently. Many people around the world continue to swear fealty to traditional beliefs, sometimes intolerant ones. And although they are much wealthier these days, they often have an us-and-them contempt for others.

The World Values Survey takes place every five years. The latest results, which go up to 2022, canvassed almost 130,000 people in 90 countries. Some places, such as Russia and Georgia, are not becoming more tolerant as they grow, but more tightly bound to traditional religious values instead. At the same time, young people in Islamic and Orthodox countries are barely more individualistic or secular than their elders. By contrast, the young in northern Europe and America are racing ahead. Countries where burning the Koran is tolerated and those where it is a crime look on each other with growing incomprehension.

On the face of it, all this supports the campaign by China’s Communist Party to dismiss universal values as racist neo-imperialism. It argues that white Western elites are imposing their own version of freedom and democracy on people who want security and stability instead.

In fact, the survey suggests something more subtle. Contrary to the Chinese argument, universal values are more valuable than ever. Start with the subtlety. China is right that people want security. The survey shows that a sense of threat drives people to seek refuge in family and racial or national groups, while tradition and organised religion offer solace.

This is one way to see America’s doomed attempts to establish democracy in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as the failure of the Arab spring. Amid lawlessness and upheaval, some people sought safety in their tribe or their sect. Hoping that order would be restored, some welcomed the return of dictators.

The subtlety the Chinese argument misses is the fact that cynical politicians sometimes set out to engineer insecurity because they know that frightened people yearn for strongman rule. That is what Bashar al-Assad did in Syria when he released murderous jihadists from his country’s jails at the start of the Arab spring. He bet that the threat of Sunni violence would cause Syrians from other sects to rally round him.

Something similar happened in Russia. After economic collapse and jarring reforms in the 1990s, Russians thrived in the 2000s. Between 1999 and 2013, gdp per head increased 12-fold in dollar terms. Yet that did not dispel their accumulated dread. President Vladimir Putin consistently played on their ethno-nationalist insecurities, especially when growth later faltered. That has culminated in his disastrous invasion of Ukraine.

Even in established democracies, polarising politicians like Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, former presidents of America and Brazil, saw that they could exploit left-behind voters’ anxieties to mobilise support. So they set about warning that their political opponents wanted to destroy their supporters’ way of life and threatened the very survival of their countries. That has, in turn, spread alarm and hostility on the other side.

Even allowing for this, the Chinese claim that universal values are an imposition is upside down. From Chile to Japan, the World Values Survey provides examples where growing security really does seem to lead to tolerance and greater individual expression. Nothing suggests that Western countries are unique in that. The real question is how to help people feel more secure.

China’s answer is based on creating order for a loyal, deferential majority that stays out of politics and avoids defying their rulers. However, within that model lurks deep insecurity. It is a majoritarian system in which lines move, sometimes arbitrarily or without warning—especially when power passes unpredictably from one party chief to another.

A better answer comes from prosperity built on the rule of law. Wealthy countries have more resources to spend on dealing with disasters, such as pandemic disease. Likewise, confident in their savings and the social safety-net, the citizens of rich countries know that they are less vulnerable to the chance events that wreck lives elsewhere.

Universal and valuable

However, the deepest solution to insecurity lies in how countries cope with change, whether from global warming, artificial intelligence or the growing tensions between China and America. The countries that manage change well will be better at making society feel confident in the future. And that is where universal values come into their own. Tolerance, free expression and individual inquiry help harness change through consensus forged by reasoned debate and reform. There is no better way to bring about progress.

Universal values are much more than a Western piety. They are a mechanism that fortifies societies against insecurity. What the World Values Survey shows is that they are also hard-won.