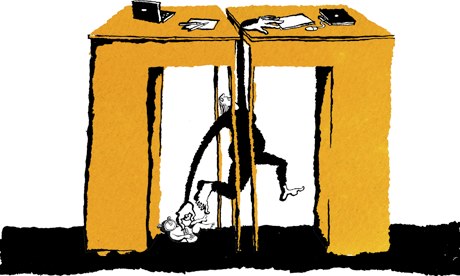

'The idea that you can plan high-quality childcare or a work-life balance in zero-hours conditions is laughable.' Illustration by Belle Mellor

Crack open a conversation about the family in political circles, and it's like Christmas Day in the trenches. Agreement breaks out: there's nothing more important than security, happiness and high-quality childcare in the early years; every child matters; women deserve their place in the workforce, men deserve their time in the homestead; both genders are desperately welcome – invaluable, irreplaceable! – in all settings; and (altogether now) we all want to be more like Scandinavia.

Delving a little deeper, there are some disagreements between the parties, or – for brevity – between Liz Truss, the childcare minister, and everybody else. Labour and the Lib Dems think the answer to universal, high-quality childcare is to find some equitable way for the government to fund it. Truss still thinks that the market would work on its own, if only big government would step out of the way. Her plan is for childcare workers to be better trained, and therefore allowed to manage more children. It is a stupid plan. No amount of GCSEs will increase your number of arms, hands and eyes. Yet she is to be admired for breaking ranks and allowing her neoliberalism free expression. Nobody else will mention market forces devant les enfants; it's almost as if the market were some kind of swearword.

And yet, despite every advance, every warm progressive statement, every assurance of "family-friendliness", conditions for parents at work worsen; discrimination against pregnant women intensifies . The rather nugatory fortnight of paternity leave goes largely unclaimed among low-income workers, while 80% of those on middle to high incomes take it. Most low-waged mothers go back to work after fewer than the 26 weeks of "ordinary maternity leave", most mothers on medium to high incomes take more than six months.

There is a gulf between the promises made to families by politicians, and the life that is delivered. There is also a gulf between rich and poor, which is then biologised by the likes of Iain Duncan Smith and his Centre for Social Justice, who blame "bad parenting" on poor people who don't love their babies enough to want to spend their first year with them. But we're just going to have to do that another day.

I believe the work situation is substantially down to the way we talk about life in gender silos, where "children", "maternity leave", "pregnancy" and "families" are filed under "women", while "industrial relations", "tribunals", "contracts" and "workplace" go under "men". This has blinded us to the fact that many statutory entitlements can never be upheld. Maybe you have the wrong kind of job or the wrong kind of (zero hours) contract; some rights build up over time and you can't prove unbroken service if you've never had a proper contract. Even if you could, your position is too precarious to insist on the rights you do have; and if it all turns sour you can't take anybody to a tribunal because since last July you've had to pay to do so.

The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development recently released research on the reality of zero-hours work: 75% of workers didn't know how much money they'd have at the end of the week, and 42% were given less than 12 hours' notice about shifts. The idea that you can plan "high-quality childcare" in these conditions, or a favourable work-life balance, is laughable.

By way of illustration, I saw this advert in Costa Coffee (Eastleigh, Hampshire) the other day: "Staff wanted … 20 hours a week. MUST BE FREE 6AM TO 9PM, SEVEN DAYS A WEEK". Never mind, says the Office for National Statistics – only 0.7% of people are on zero hours; but this amounts to 250,000 workers. Norman Lamb, the care minister, has admitted to 300,000 zero-hours workers in social care. A Working Families report this week finds 7% of women and over 2% of men on zero hours.

The CIPD put the number of zero-hours workers at about a million. But try to stay cheerful – they still have rights: sick pay; minimum wage; holiday pay; maternity leave. Sure, it doesn't stretch to the right to request flexible working, which could explain why requests from fathers on low incomes are so often refused. Nevertheless, it's not like working in a mill in the 19th century.

Except that, often, it is. This employment feels too precarious for people to insist on the rights they do have, and anyway those rights are sidestepped by a week-long break in the job (easily within the employer's command). And let's say your employer reneges on your maternity package: well, it will cost you £1,200 to bring that to a tribunal. The drop in sex discrimination claims has been stark: there were 129 in September – the average for the six months before the charge was brought in was 2,055 . "We have to be careful we're not just talking about paper rights," said Sally Brett from the TUC

Back in 2011, Steve Hilton floated the idea across his blue sky that maybe maternity leave should be abolished, just while we were in recession, so business could get back on its feet, without having to worry about a load of uteruses? And we all (well, I) went nuts, saying: "This recasts women as burdens to work instead of assets, and remakes babies as costs for the tidy, solitary little household to bear, rather than a future for us all to invest in." Well, they goddam did it anyway, and you have to admire their cunning: they didn't torch the right; they torched the ability to claim the right. It became a paper right, and now we watch as it goes up in smoke.