Richard P Grant in The Guardian

A video did the rounds a couple of years ago, of some self-styled “skeptic” disagreeing – robustly, shall we say – with an anti-vaxxer. The speaker was roundly cheered by everyone sharing the video – he sure put that idiot in their place!

Scientists love to argue. Cutting through bullshit and getting to the truth of the matter is pretty much the job description. So it’s not really surprising scientists and science supporters frequently take on those who dabble in homeopathy, or deny anthropogenic climate change, or who oppose vaccinations or genetically modified food.

It makes sense. You’ve got a population that is – on the whole – not scientifically literate, and you want to persuade them that they should be doing a and b (but not c) so that they/you/their children can have a better life.

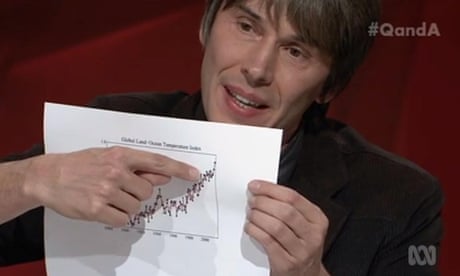

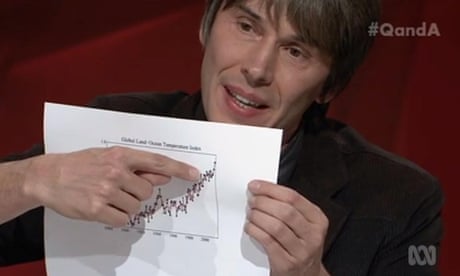

Brian Cox was at it last week, performing a “smackdown” on a climate change denier on the ABC’s Q&A discussion program. He brought graphs! Knockout blow.

Q&A smackdown: Brian Cox brings graphs to grapple with Malcolm Roberts

And yet … it leaves me cold. Is this really what science communication is about? Is this informing, changing minds, winning people over to a better, brighter future?

I doubt it somehow.

There are a couple of things here. And I don’t think it’s as simple as people rejecting science.

First, people don’t like being told what to do. This is part of what Michael Gove was driving at when he said people had had enough of experts. We rely on doctors and nurses to make us better, and on financial planners to help us invest. We expect scientists to research new cures for disease, or simply to find out how things work. We expect the government to try to do the best for most of the people most of the time, and weather forecasters to at least tell us what today was like even if they struggle with tomorrow.

But when these experts tell us how to live our lives – or even worse, what to think – something rebels. Especially when there is even the merest whiff of controversy or uncertainty. Back in your box, we say, and stick to what you’re good at.

We saw it in the recent referendum, we saw it when Dame Sally Davies said wine makes her think of breast cancer, and we saw it back in the late 1990s when the government of the time told people – who honestly, really wanted to do the best for their children – to shut up, stop asking questions and take the damn triple vaccine.

Which brings us to the second thing.

On the whole, I don’t think people who object to vaccines or GMOs are at heart anti-science. Some are, for sure, and these are the dangerous ones. But most people simply want to know that someone is listening, that someone is taking their worries seriously; that someone cares for them.

It’s more about who we are and our relationships than about what is right or true.

This is why, when you bring data to a TV show, you run the risk of appearing supercilious and judgemental. Even – especially – if you’re actually right.

People want to feel wanted and loved. That there is someone who will listen to them. To feel part of a family.

The physicist Sabine Hossenfelder gets this. Between contracts one time, she set up a “talk to a physicist” service. Fifty dollars gets you 20 minutes with a quantum physicist … who will listen to whatever crazy idea you have, and help you understand a little more about the world.

How many science communicators do you know who will take the time to listen to their audience? Who are willing to step outside their cosy little bubble and make an effort to reach people where they are, where they are confused and hurting; where they need?

Atul Gawande says scientists should assert “the true facts of good science” and expose the “bad science tactics that are being used to mislead people”. But that’s only part of the story, and is closing the barn door too late.

Because the charlatans have already recognised the need, and have built the communities that people crave. Tellingly, Gawande refers to the ‘scientific community’; and he’s absolutely right, there. Most science communication isn’t about persuading people; it’s self-affirmation for those already on the inside. Look at us, it says, aren’t we clever? We are exclusive, we are a gang, we are family.

That’s not communication. It’s not changing minds and it’s certainly not winning hearts and minds.

It’s tribalism.

Ben Chu in The Independent

Big numbers are all around us, shaping our political debates, influencing the way we think about things. For instance we hear a great deal about the prodigious size of the national debt: £1,603bn in July according to the latest official statistics.

There has been a proliferation of stories about the aggregate deficit of pension schemes, which has jumped to an estimated £1trn in the wake of the Brexit vote. And how could we forget that record net migration figure of 333,000, which figured so prominently in the recent European Union referendum campaign?

Yet there are other massive numbers we seldom hear about. The Office for National Statistics published some estimates for the “national balance sheet” last week. This is the place to look if you want really big numbers. They showed that the aggregate value of the UK’s residential housing stock in 2015 was £5.2 trillion – that’s up £350bn in just 12 months. A lot of people are a lot wealthier than they were a year ago.

That’s property wealth. What about the total value of households’ financial assets? According to the ONS, that stands at £6.2 trillion – up £113bn over the year. It will be even higher since the Brexit vote. Why? Because those ballooning pension scheme deficits we hear about represent a part of the financial assets of households.

Incidentally, a majority of the national debt, indirectly, represents a financial asset of UK households too. We often forget that for every financial liability there has to be a financial asset.

There’s still a good deal of handwringing in some quarters about the supposedly excessive borrowing of the state. But we don’t tend to hear anything about the debt of the corporate sector these days. The ONS reports that the total debt (loans and bonds combined) of British-based companies in 2015 was £1.35 trilion, pretty much where it was back in 2010.

If debt is something to get excited about, shouldn’t company borrowing be a cause for concern? Not, of course, if companies are borrowing to increase their productive capacities.

Actually, the major problem with corporate balance sheets lies in a different area. The ONS data shows that the corporate sector’s overall stocks of cash rose to £581bn in 2015, up £41bn on last year and a sum representing an astonishing 31 per cent of our GDP. It should be seriously worrying that firms are still choosing to keep so much cash on their balance sheets at a time when we badly need them to invest.

We tend to fret about the wrong big numbers. Consider the data on the liabilities of UK-based financial institutions. If you want a large number try this: £20.5 trillion. And around a quarter of these are financial derivative contracts. Many of those companies are foreign firms with UK operations. But UK banks – which we taxpayers still effectively underwrite because they are “too big to fail” – have aggregate liabilities worth £7.5 trillion.

That’s around four times larger than our GDP, yet Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, has rather strangely suggested he would be comfortable with that figure eventually rising to nine times national income.

Sometimes we fail to appreciate what lies behind the big numbers that shape our debates. The headlines this week said total UK employment grew by 172,000 in the three months to June. But this only tells one part of the story. Other data from the ONS showed that 478,000 people without jobs got them in the quarter, while 317,000 people entered the ranks of the unemployed. That headline figure is a net change in employment figure. And this wasn’t an unusually busy quarter for the jobs market.

This churn goes on constantly, with hundreds of thousands of us leaving jobs and hundreds of thousands taking new ones. The economic threat from the Brexit vote aftermath isn’t just people being made redundant – it’s a slowdown in hiring and that mighty labour market churn.

There’s a similar issue with those ubiquitous net migration figures. Newspapers talk of immigration creating “a new city the size of Newcastle each year” (or some variation on that line). That is rhetoric designed to stir public anxiety.

Yet that’s in context of an estimate of 36 million tourist visits to the UK each year, flows equal to half of the British population. And there are double the number of tourists visits going the other way each year.

What these big numbers emphasise is that we live in a mind-bendingly busy, complex and internationally connected economy. The figures we hear about, and which pundits fixate upon, are often the differences between two, or sometimes more, very large numbers. That bigger context should not be ignored.

The economic risks and fragilities of our economy are not always where we’re invited to believe they are.

Paul Mason in The Guardian

If you walk along Britain’s poorest streets, the phrase “left behind” – in vogue again after many such places voted to leave the EU – takes on a complex meaning. It’s not just that they are lagging behind the richer, better-connected places. It can seem, as you survey the pound stores and shuttered pubs, that these towns have been discarded: left behind, as in “unwanted on the journey”. Wealth has flowed out of them to somewhere else.

The logical question should be: who did this? Sometimes it’s obvious: in Ebbw Vale, for example, the answer is the Anglo-Dutch steel company Corus, which closed the plant in 2002. In many places it’s not obvious. Jobs seep away; council services are privatised; bus timetables dwindle; the local school gets taken over by a “superhead” from somewhere else, outsourcing the dinner ladies on day one. You can get angry about it, but there is nobody specific to be angry at.

Faced with the same problem, union and community organisers in the US have, in the past 12 months, adopted a novel way of fighting back. Through a campaign group called Hedge Clippers, they have begun tracing the lineages of financial power behind the decisions that affect specific places, and targeting those financiers – pension funds – with a new kind of pressure.

Steve Lerner, one of the instigators of the 1980s Justice for Janitors campaign, which, for the first time, organised migrant cleaning workers in the US, explains how the tactic evolved. “We were organising janitors working for contract cleaning companies: but they’re just middlemen,” he said. “So we targeted the building owners. It turned out they, too, were dependent on banks and pension companies, so we got a trillion dollars worth of pension money to say it won’t invest unless there is decent pay. Then we asked ourselves: OK, what else do they own?”

It turns out, quite a lot. In Baltimore, the city’s privatised water industry hiked its bills. Then, when people started to fall behind in payments, the city agreed to bundle up their unpaid bills into a financial vehicle called a “tax lien” and sell it to investors. The investors can, after two years, evict people from their homes for non-payment.

When campaigners looked at who was buying up the debt, they included an anonymous company linked to one of the biggest hedge funds in America: Fortress Investments, with $23bn worth of assets invested in “the largest pension funds, university endowments and foundations”.

Since the 2008 crisis, with returns on government bonds negative, and stock market dividends depressed, pension funds have been pouring money into the hedge fund sector. “It’s a form of assisted suicide,” Lerner argues: “Workers are investing their pension money into firms whose mission is to destroy us.”

He set up Hedge Clippers, which aims to force pension funds to divest from companies whose investment strategies fuel the cycle of impoverishment.

If you apply the same approach to Britain, you’re dealing with a different ecosystem. No city has yet securitised the unpaid debts of the poor, as Baltimore did. While there is no shortage of predatory lenders to the poor, there are – after a campaign led by Labour MP Stella Creasy – at least elementary controls on them.

However, pension funds are now the biggest source of money for UK hedge funds, according to a Financial Conduct Authority survey last year, with 43% of their money coming from institutional investors. The most obvious act of financial predation is the private finance initiative (PFI), where schools and hospitals were built with vastly lucrative private loans. As a result, the taxpayer is committed to paying back £232bn on assets worth £57bn.

Many pension funds, either directly or indirectly, are investing in the so-called “infrastructure funds” who buy up PFI debt. The investment analyst Preqin found 588 institutional investors worldwide with “a preference for funds targeting PFI”, 40% of which were based in Europe.

Tracing the more complex ways institutional finance is funding the cycle of impoverishment is not easy. What you would want to know, in places such as Stoke-on-Trent or Newport, is not just who took the decisions to close high-value workplaces but, more importantly, who makes the decisions that lead to chronic under-investment now. Governments, including the devolved ones of the UK, spend a lot of time and money effectively bribing global companies to create jobs and keep them in Britain’s depressed areas. Communities themselves have little or no input into the process, which is in any case all carrot and no stick.

Lerner’s initiative in the US grew out of trade union activism, because the unions there learned to follow the money instead of wasting time trying to negotiate with the powerless underlings of global finance. They worked out that, in an age where the workplace and the community can seem like two different spheres of activism, it is the finance system that links the two.

Older ‘left-behind’ voters turned against a political class with values opposed to theirs

Union organising of the unorganised, and community activism in Britain have both traditionally been weak because top-down Labourism has been strong. Faced with PFI, predatory loans, rip-off landlords and privatisation, the British way is to demand legislation, not chain yourself to the door of a Mayfair hedge fund.

With or without Jeremy Corbyn, the near-impossibility of Labour gaining a Commons majority in 2020 – whether because of Scotland, boundary changes, a hostile media or self-destruction – has to refocus the left on to what is possible to achieve from below. We have to start, as the Americans did, by mapping the invisible forces that strip jobs, value and hope out of communities; make them visible; trace their dependencies and then use direct action to kick them in the corporate goolies until they desist.

Joseph Stiglitz in The Guardian

To say that the eurozone has not been performing well since the 2008 crisis is an understatement. Its member countries have done more poorly than the European Union countries outside the eurozone, and much more poorly than the United States, which was the epicentre of the crisis.

The worst-performing eurozone countries are mired in depression or deep recession; their condition – think of Greece – is worse in many ways than what economies suffered during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The best-performing eurozone members, such as Germany, look good, but only in comparison; and their growth model is partly based on beggar-thy-neighbour policies, whereby success comes at the expense of erstwhile “partners”.

Four types of explanation have been advanced to explain this state of affairs.Germany likes to blame the victim, pointing to Greece’s profligacy and the debt and deficits elsewhere. But this puts the cart before the horse: Spain and Ireland had surpluses and low debt-to-GDP ratios before the euro crisis. So the crisis caused the deficits and debts, not the other way around.

Deficit fetishism is, no doubt, part of Europe’s problems. Finland, too, has been having trouble adjusting to the multiple shocks it has confronted, with GDP in 2015 around 5.5% below its 2008 peak.

Other “blame the victim” critics cite the welfare state and excessive labour-market protections as the cause of the eurozone’s malaise. Yet some of Europe’s best-performing countries, such as Sweden and Norway, have the strongest welfare states and labour-market protections.

Many of the countries now performing poorly were doing very well – above the European average – before the euro was introduced. Their decline did not result from some sudden change in their labour laws, or from an epidemic of laziness in the crisis countries. What changed was the currency arrangement.

The second type of explanation amounts to a wish that Europe had better leaders, men and women who understood economics better and implemented better policies. Flawed policies – not just austerity, but also misguided so-called structural reforms, which widened inequality and thus further weakened overall demand and potential growth – have undoubtedly made matters worse.

But the eurozone was a political arrangement, in which it was inevitable that Germany’s voice would be loud. Anyone who has dealt with German policymakers over the past third of a century should have known in advance the likely result. Most important, given the available tools, not even the most brilliant economic tsar could not have made the eurozone prosper.

The third set of reasons for the eurozone’s poor performance is a broader rightwing critique of the EU, centred on the eurocrats’ penchant for stifling, innovation-inhibiting regulations. This critique, too, misses the mark. The eurocrats, like labour laws or the welfare state, didn’t suddenly change in 1999, with the creation of the fixed exchange-rate system, or in 2008, with the beginning of the crisis. More fundamentally, what matters is the standard of living, the quality of life. Anyone who denies how much better off we in the west are with our stiflingly clean air and water should visit Beijing.

That leaves the fourth explanation: the euro is more to blame than the policies and structures of individual countries. The euro was flawed at birth. Even the best policymakers the world has ever seen could not have made it work. The eurozone’s structure imposed the kind of rigidity associated with the gold standard. The single currency took away its members’ most important mechanism for adjustment – the exchange rate – and the eurozone circumscribed monetary and fiscal policy.

In response to asymmetric shocks and divergences in productivity, there would have to be adjustments in the real (inflation-adjusted) exchange rate, meaning that prices in the eurozone periphery would have to fall relative to Germany and northern Europe. But, with Germany adamant about inflation – its prices have been stagnant – the adjustment could be accomplished only through wrenching deflation elsewhere. Typically, this meant painful unemployment and weakening unions; the eurozone’s poorest countries, and especially the workers within them, bore the brunt of the adjustment burden. So the plan to spur convergence among eurozone countries failed miserably, with disparities between and within countries growing.

This system cannot and will not work in the long run: democratic politics ensures its failure. Only by changing the eurozone’s rules and institutions can the euro be made to work. This will require seven changes:

• abandoning the convergence criteria, which require deficits to be less than 3% of GDP

• replacing austerity with a growth strategy, supported by a solidarity fund for stabilisation

• dismantling a crisis-prone system whereby countries must borrow in a currency not under their control, and relying instead on Eurobonds or some similar mechanism

• better burden-sharing during adjustment, with countries running current-account surpluses committing to raise wages and increase fiscal spending, thereby ensuring that their prices increase faster than those in the countries with current-account deficits;

• changing the mandate of the European Central Bank, which focuses only on inflation, unlike the US Federal Reserve, which takes into account employment, growth, and stability as well

• establishing common deposit insurance, which would prevent money from fleeing poorly performing countries, and other elements of a “banking union”

• and encouraging, rather than forbidding, industrial policies designed to ensure that the eurozone’s laggards can catch up with its leaders.

From an economic perspective, these changes are small; but today’s eurozone leadership may lack the political will to carry them out. That doesn’t change the basic fact that the current halfway house is untenable. A system intended to promote prosperity and further integration has been having just the opposite effect. An amicable divorce would be better than the current stalemate.

Of course, every divorce is costly; but muddling through would be even more costly. As we’ve already seen this summer in the United Kingdom, if European leaders can’t or won’t make the hard decisions, European voters will make the decisions for them – and the leaders may not be happy with the results.