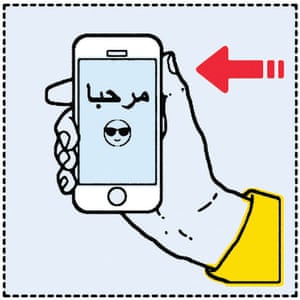

On March 26 this year, Hasan Aldewachi was on his way back from a science conference in Vienna, and looking forward to seeing his family. As he took his seat on the flight to Gatwick, he sent his wife a text message to let her know the plane was delayed. A woman sitting across the aisle got up and left her seat. Moments later the police arrived.

The Iraqi-born Sheffield Hallam student was asked to leave the plane and held for four hours. After his phone was confiscated, he was left at the airport with no onward ticket or refund. The reason? His message was in Arabic.

Aldewachi’s story is just one example of the dangers of what has become known as “flying while Muslim”; the tongue-in-cheek term for the discrimination many Muslim passengers feel they have faced at airports since 9/11. It can range from extra questions from airport staff, to formal searches by police, to secondary security screenings and visa problems when visiting America. Sometimes it feels like every Muslim has a tale to tell.

Faizah Shaheen … reading about Syria. Photograph: Twitter

Two weeks ago, a Muslim couple celebrating their wedding anniversary were removed from a flight from France to the US. A crew member allegedly complained that Nazia Ali, 34, who wears a headscarf, was using her phone, and her husband Faisal was sweating. The flight attendant allegedly also complained that the couple used the word “Allah”. The airline in question subsequently said it was “deeply committed to treating all of our customers with respect”.

Other examples this summer include NHS mental-health worker Faizah Shaheen who was on her way back from her honeymoon when she was detained and questioned by police under schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act. Cabin crew on her outbound flight said they had spotted her reading a book about Syria. Shaheen said she was left in tears by the experience. Thomson airlines said: “Our crew are trained to report any concerns they may have as a precaution.”

Two weeks ago, a Muslim couple celebrating their wedding anniversary were removed from a flight from France to the US. A crew member allegedly complained that Nazia Ali, 34, who wears a headscarf, was using her phone, and her husband Faisal was sweating. The flight attendant allegedly also complained that the couple used the word “Allah”. The airline in question subsequently said it was “deeply committed to treating all of our customers with respect”.

Other examples this summer include NHS mental-health worker Faizah Shaheen who was on her way back from her honeymoon when she was detained and questioned by police under schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act. Cabin crew on her outbound flight said they had spotted her reading a book about Syria. Shaheen said she was left in tears by the experience. Thomson airlines said: “Our crew are trained to report any concerns they may have as a precaution.”

The stories that hit the headlines are often those similar to Aldewachi’s or Shaheen’s – where normal behaviour by Muslim passengers is seen as suspicious. More prevalent, but less reported, are the day-to-day stories of innocent passengers who feel they are under suspicion solely because of their religion.

Equality and civil liberties groups warn that the net is now being thrown so wide that it is stigmatising and alienating thousands of Muslims. This, many argue, could make our time in the air less safe by sowing seeds of division. Even high-profile Muslims cannot escape. England cricketer Moeen Ali, Cat Stevens, music producer Naughty Boyand comedian Adil Ray have all complained of discriminatory treatment at airports. This month, Four Lions actor and rapper Riz Ahmed released a single called T5, about the problems he faces on flights.

Aldewachi, who has lived in the UK since 2010, is still shaken by his experience. “Everyone was looking at me and assuming I had done something wrong. This is not vigilance. This is stereotyping,” he says.

He has received no apology from the Austrian police – and says that apart from being told that a female passenger had reported seeing “something related to Isis” – he was given no further explanation. The biomedical scientist finally received an apology and refund from easyJet after his story was reported in a newspaper.

Aldewachi thinks the focus on terrorism in the media hasn’t helped. “People who know me are astonished. I am calm and quiet – they can’t understand why anyone would look at me and be afraid.

“To compare it to something in my field, it’s like swine flu. Everyone thought they had it because they heard so much about it.”

Khairuldeen Makhzoomi can sympathise. In April, the 26-year-old was on his way back to his university in California when he phoned his uncle in Iraq to tell him he had been invited to a formal dinner at which Ban Ki-moon would be present – he even asked the UN secretary general a question. A woman in front of him reported him and Makhzoomi was asked to leave the plane, confronted by police officers, and had his bag searched in front of other passengers. The politics student says the airline manager told him he should have known it was a security risk to “speak that language”. However, the airline, Southwest, released a statement saying it was the content of his words that was “perceived to be threatening,” not his use of Arabic.

In March, a London DJ, Mehary Yemane-Tesfagiorgis, was removed from a flight from Rome because a passenger said they didn’t feel safe travelling with him. Yemane-Tesfagiorgis, who is black, said he was a victim of racial profiling.

Fellow Londoner, Laolu Opebiyi, a Nigerian-born Christian, was asked to leave a plane after another passenger saw a prayer group message on his phone, labelled “Isi” (an acronym for “iron sharpens iron”, a Biblical quotation). Earlier this month Guido Menzio, a University of Pennsylvania economics professor who has “curly, dark hair”, was expelled from a plane in the US after the equations he was writing alarmed a female passenger.

In the US, so many Sikhs have been subjected to extra screening because of their clothing that the Sikh Coalition has launched an app to highlight cases of discrimination. Katy Sian, a lecturer at the University of York who has been researching the problems faced by Sikhs at airports, says the issue highlights “how brown, male bodies are caught up in the war on terror”.

When I asked family and friends for their experiences of “flying while Muslim” the stories came thick and fast. A friend recounted being prevented from boarding and questioned by secruity officials. A Guardian editor was stopped and questioned four out of the seven times he travelled to the US, including being asked about attending training camps in the Middle East.

A relative of mine, who lives in the UK, and has both US and UK passports, is stopped on “80% of my trips to, or within, the US – and I travel there about five or six times a year”.

It began soon after 9/11 on a layover in Minnesota. A police officer asked him to confirm his name and then to accompany him for questioning.

“When I asked him what it was about, he said the pilot had said I had been belligerent on the flight. I immediately switched to being as American as possible. I said something like, ‘Yo, dude, that’s totally ridiculous. I didn’t speak to anyone.’ I said he seemed like a nice guy, but this was racist profiling. When I said that, he apologised and said his boss had told him to check me out.”

Now he arrives early for flights in the US to factor in the extra security screening. “Once, they told me it was a ‘random’ selection and when I asked what it was based on, they said: ‘Name, age, ethnicity.’

2. ‘Do not speak foreign.’ Illustration: Son of Alan/Folio

“In Turkey, I was told I had the same name as a terrorist’s son, and that the US shares their watchlist with them.

“I always put up a fight because the way they treat you is terrible. My view is that I am practically a boy scout. If I don’t say something, who will?”

Hugh Handeyside, from the American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU], explains that repeatedly having “SSSS” (secondary security screening selection) printed on your boarding pass is a “strong indication” your name has made it to a subset of the US government’s sprawling terrorism watchlist. Sometimes it is enough to have a name similar to someone who is on the list.

The database is believed to contain hundreds of thousands of names, and the secrecy surrounding it is intensely controversial. In April the Council of American Islamic Relations’ [Cair] Michigan branch launched a class action on behalf of the “thousands of innocent Americans who were wrongfully designated as ‘known or suspected terrorists’ without due process”, and another lawsuit seeking a “declaration that the watchlist is unconstitutional”.

Handeyside says that lawsuits by the ACLU have revealed that travel to a particular country in a particular year have been given as reasons for inclusion on a different subset of the watchlist – the no-fly list.

In 2014, leaked details showed that those of Muslim descent were disproportionately represented on the list; while New York had the most watchlisted people, the second was Dearborne, a small city in Michigan. As Handeyside points out, Dearborne is “the centre of the highest concentration of people of Arab descent outside the Middle East”. The use of algorithms to determine who required extra screening renders the system even more opaque.

The attorney, who spent two years working for the CIA, says the huge numbers involved mean the watchlists are not making us safer. “It increases the size of the haystack – if there is a needle in there it is so much harder to find … it immeasurably increases the white noise.”

For cases of mistaken identity, there is a redress system. Cair says even this is wrapped in secrecy and the only way to find out if you have been successful is by flying again.

Campaigners say few Muslims are willing to complain officially about their treatment at airports. The stigma of being accused of being a terrorist, even if the accusations are unwarranted, can be enough to silence many. Others fear a backlash from the authorities.

Handeyside says those who easily dismiss such experiences don’t always realise the toll it can take. “We can’t underestimate how stigmatising and unpleasant it is to have to go through this every single time – to have everyone looking at you and thinking you are a terrorist.”

Imam Ajmal Masroor, was so incensed by his own treatment at an airport that he set up a website to collate other people’s stories. Having travelling to and from the States several times in 2015, he was stopped by US Embassy officials at the airport in December and abruptly told his business visa had been revoked.

Masroor, 44, who says he has received death threats for speaking out against terrorism in the past, explains he was eventually told the problem was someone on his Facebook page, “but I have 30,000 followers so I don’t know who that is”. And despite a letter from the State Department saying the revocation was an error, he says visits to the US embassy have not rectified the situation.

One politician trying to discover the scale of the problem is the MP Stella Creasy. She has been asking questions about US Homeland Security issues after a family of 11 from her Walthamstow constituency were stopped at the airport as they made their way to Disneyland. The family lost $13,340 by missing their flights, which they were told would not be refunded. The trauma is, of course, impossible to quantify. “Their Esta visa was revoked. The kids were crying. They had to give back everything they had bought from duty free – it was horrible. Why not tell them before they get to the airport?”

3. ‘Allow extra time to clear security.’ Illustration: Son of Alan/Folio

When she heard similar stories from other constituents she asked questions in parliament, but was told no figures about how many UK citizens are barred from visiting the US are kept. While UK authorities publish stop-and-search data, broken down by ethnicity, the US is less transparent.

“There is confirmation that Homeland Security officials are working out of Manchester, Gatwick and Heathrow airports, but under what auspices is unclear,” she says. “If we have the data, we can either allay fears or do something about it. But the government doesn’t know, and that should worry us.”

Now she is hoping to launch a legal case challenging the government over the lack of figuresm, insisting it is a failure of their public sector equality duty.

“No one is suggesting that there should not be checks. It’s the lack of information and scrutiny that is the problem.”

A US embassy spokesperson stressed that religion, faith, or spiritual beliefs were not determining factors about admissibility into the US. US Customs and Border Protection confirmed it did not disclose the percentage of travellers selected for secondary inspection or breakdown their figures by ethnicity. However, a spokesperson said the numbers were “almost insignificant” compared with the volume of travellers arriving from the UK every day.

SNP MSP Humza Yousaf with party leader Nicola Sturgeon Photograph: Danny Lawson/PA

While the UK may keep figures for stop and searches at airports, that doesn’t mean there are no problems. In 2012 Glasgow airport faced a boycott from Muslim passengers, who said they were fed up with being harassed by counter-terrorism officers. A year earlier, the Scottish MSP Humza Yousaf revealed he had been been stopped under schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000. It wasn’t the first time he was stopped.

Under the original legislation of this stop-and-search law act, anyone entering or leaving the UK could be held for up to nine hours with no grounds for suspicion needed. At its peak in 2009/10, 85,000 travellers a year were stopped and ethnic minorities were 42 times more likely to be stopped than white passengers.

Yousaf said his frequent stops illustrated that they were based on skin colour, not intelligence information.

In 2014, after strong criticism, there was a change in the law referring to schedule 7 stops. The presence of a solicitor was required and the maximum detention time was reduced to six hours. It led to a dramatic drop in those stopped. The latest available data shows a considerably lower number – in 2015, a fall of 21% on the previous year. David Anderson, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, says this, in part, is down to an increased focus on data and behavioural analysis and a “reduced reliance on intuitive stops”. Anderson does not believe the statistics show schedule 7 powers are being used in a racially discriminatory manner, although he acknowledges the stops cause “considerable irritation for travellers of all ethnicities” while “arrest rates remain very low indeed by the standards of stop and search”. Five supreme court judges reviewed his analysis and while four agreed, one believed “schedule 7 not only permits direct discrimination; it is entirely at odds with the notion of an enlightened pluralistic society”.

While the UK may keep figures for stop and searches at airports, that doesn’t mean there are no problems. In 2012 Glasgow airport faced a boycott from Muslim passengers, who said they were fed up with being harassed by counter-terrorism officers. A year earlier, the Scottish MSP Humza Yousaf revealed he had been been stopped under schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000. It wasn’t the first time he was stopped.

Under the original legislation of this stop-and-search law act, anyone entering or leaving the UK could be held for up to nine hours with no grounds for suspicion needed. At its peak in 2009/10, 85,000 travellers a year were stopped and ethnic minorities were 42 times more likely to be stopped than white passengers.

Yousaf said his frequent stops illustrated that they were based on skin colour, not intelligence information.

In 2014, after strong criticism, there was a change in the law referring to schedule 7 stops. The presence of a solicitor was required and the maximum detention time was reduced to six hours. It led to a dramatic drop in those stopped. The latest available data shows a considerably lower number – in 2015, a fall of 21% on the previous year. David Anderson, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, says this, in part, is down to an increased focus on data and behavioural analysis and a “reduced reliance on intuitive stops”. Anderson does not believe the statistics show schedule 7 powers are being used in a racially discriminatory manner, although he acknowledges the stops cause “considerable irritation for travellers of all ethnicities” while “arrest rates remain very low indeed by the standards of stop and search”. Five supreme court judges reviewed his analysis and while four agreed, one believed “schedule 7 not only permits direct discrimination; it is entirely at odds with the notion of an enlightened pluralistic society”.

4. ‘Text with care.’ Illustration: Son of Alan/Folio

This year, the government published new guidance pointing out that the decision to stop someone should not be arbitrary, and ethnicity and religion should only be considered significant in association with “factors which show a connection with the threat from terrorism”. According to analysis of the 2015 figures by Faith Matters, a community-cohesion organisation, “non-whites are at least 37 times as likely as a white person to be detained at a port or airport. Asians are almost 80 times as likely as a white person to be detained at an airport or port.” Along with anecdotal evidence, this, they say, shows a “significant level of profiling that demands urgent action to ensure that British citizens and non-UK nationals visiting Britain are treated equally.”

Stefano Bonino, a criminologist at Northumbria University recently, interviewed 39 Scottish Muslims. He found while most had positive stories of “relative local harmony”, his interviewees’ experience of airports created real feelings of alienation, social inequality, “anger and humiliation”.

Philip Baum, author of Violence in the Skies, says racial profiling is unhelpful, but says there should be more behavioural analysis at airports than we have currently. “Even if an attack is being carried out under Isis or al-Qaeda that doesn’t mean it will be someone carrying it out who ‘looks’ Muslim. The classic case was the Anne Marie Murphy case in 1986, who was stopped from boarding a flight to Tel Aviv – of 1986. She was white, female and pregnant – not a stereotypical image of a terrorist.” Murphy was found to be unwittingly carrying explosives in her luggage – placed there by her Jordanian fiancé, Nezar Hindawi, who was jailed for 45 years.

Baum suggests that the widespread belief that Muslims will be targeted could in turn change their behaviour. “There is a lot of paranoia and sometimes people can be affected by that – they act suspiciously because they think they will be picked on.”

While the fear of terrorism at airports means that many people are willing to put up with more intrusive security procedures, the discriminatory experiences at airports that many Muslims recount risks creating divisions and resentment.

For Bonino the consequences are clear. “Grievance based jihadi propaganda can use things like this. When you want Muslims to work with the authorities to counter violent extremism on the ground, it’s not helpful for people to think they are targeted by the authorities themselves.”

Know your rights

The Council of American Islamic Relations guide to your rights

• A customs agent has the right to stop, detain and search every person and item.

• Screeners have the authority to conduct a further search of you or your bags.

• A pilot has the right to refuse to fly a passenger they believe is a threat to the safety of the flight. The pilot’s decision must be reasonable and based on observations, not stereotypes.

If you believe you have been treated in a discriminatory manner:

• Note the names and IDs of those involved.

• Ask to speak to a supervisor.

• Politely ask if you have been singled out because of your name, looks, dress, race, ethnicity, faith or national origin.

• Politely ask witnesses to give you their names and contact information.

• Write a statement of facts immediately after the incident. Include the flight number, the flight date and the name of the airline.

No-fly list and selectee list

You may be on the selectee list if you are unable to use the internet or the airport kiosks for automated check-in. You should eventually be permitted to fly. The no-fly list prohibits individuals from flying at all. If you are able to board an airplane, regardless of the amount of questioning or screening, then you are not on the no-fly list.

Schedule 7 guide by Faith Matters

• Under schedule 7 you can be searched, examined and detained by a police officer at a port or airport.

• If you are stopped, your person and your property may be searched, but you can request that the search of your person be conducted by someone of the same gender.

• You do not have to answer questions about other individuals or agree to snoop on any other individuals.

• You have the right to speak to a solicitor.

• If you are detained, the police are expected to take you to a police station as soon as is reasonably possible. You can be detained only up to six hours (unless you are arrested or charged). You have the right to inform “one named person” of your detention.