A GKN engineer at work. The £8bn battle for control of Britain’s third largest engineering group has been won by Melrose. Photograph: GKN

The past is never dead. When the wheeling, dealing, asset-stripping Hanson Trust finally collapsed in 2007, having played a major part in the deindustrialisation of Britain – but having greatly enriched its Thatcherite founder Lord Hanson – I thought a stake had finally being driven through the heart of a particular ghoul.

Never again would our Westminster, Whitehall and City establishments indulge a glorified super-accountant who knew the price of everything but the value of nothing. And, in the name of “culture change” and rigorous “management”, had laid waste to industrial Britain. I was wrong.

The ghoul lives on, reincarnated as Chris Miller, the executive chair of Melrose, a company self-consciously cast in Hanson Trust’s image, and now the victor in the £8bn battle for control of Britain’s third largest engineering group, GKN. Miller is in fact a Hanson protege and, like his former boss James Hanson, he trained as an accountant – the perfect professional background for asset stripping.

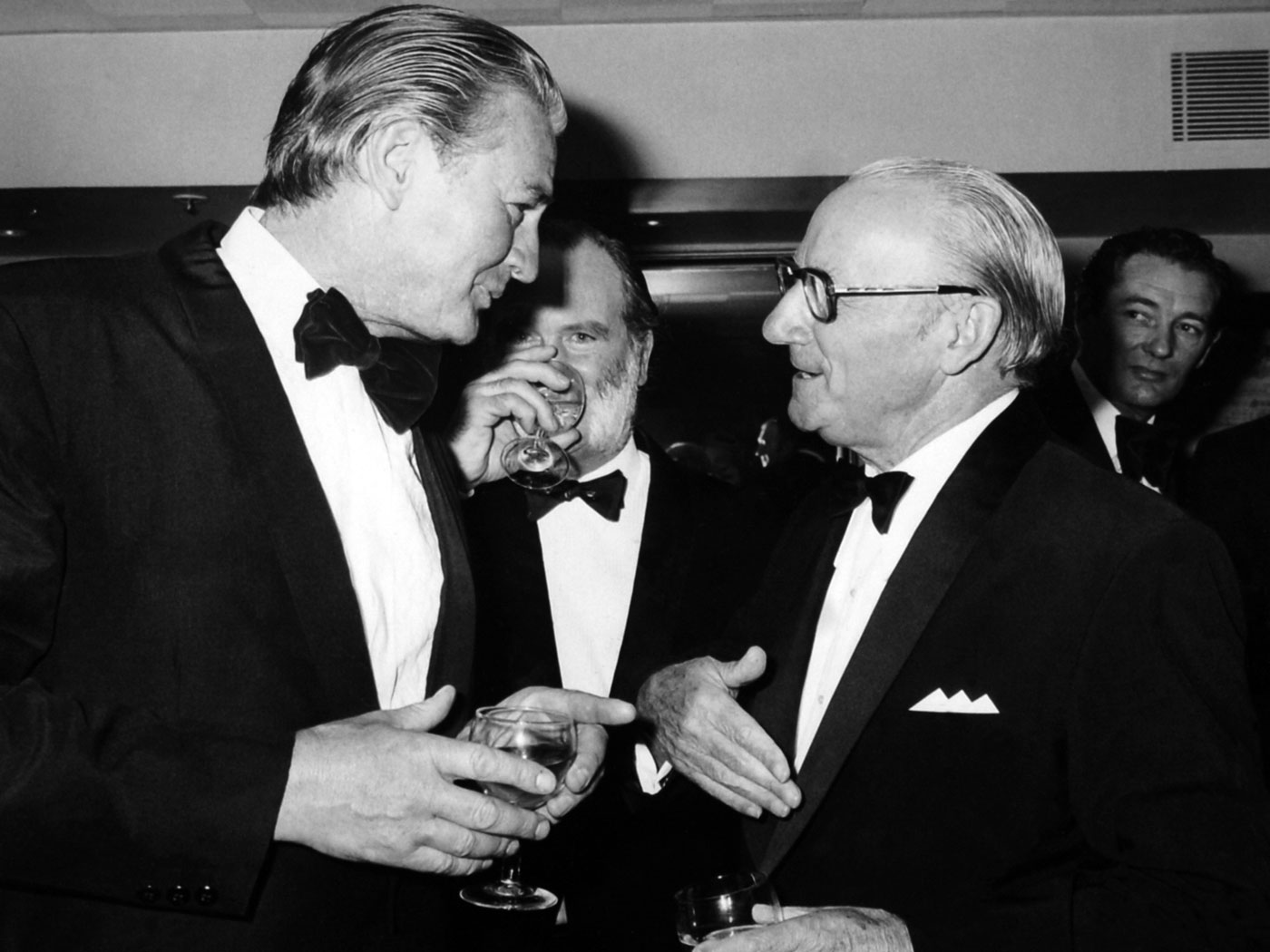

For what glory days were those! The young Miller will have been part of the finance team working to Hanson and his chief accomplice, Gordon White, at their headquarters overlooking Buckingham Palace. It was a company wholly controlled by the two men, insisting on approving every expenditure above £500 by the companies they acquired – even while they pioneered stowing profits in tax havens and raiding pension funds of the companies they took over.

The past is never dead. When the wheeling, dealing, asset-stripping Hanson Trust finally collapsed in 2007, having played a major part in the deindustrialisation of Britain – but having greatly enriched its Thatcherite founder Lord Hanson – I thought a stake had finally being driven through the heart of a particular ghoul.

Never again would our Westminster, Whitehall and City establishments indulge a glorified super-accountant who knew the price of everything but the value of nothing. And, in the name of “culture change” and rigorous “management”, had laid waste to industrial Britain. I was wrong.

The ghoul lives on, reincarnated as Chris Miller, the executive chair of Melrose, a company self-consciously cast in Hanson Trust’s image, and now the victor in the £8bn battle for control of Britain’s third largest engineering group, GKN. Miller is in fact a Hanson protege and, like his former boss James Hanson, he trained as an accountant – the perfect professional background for asset stripping.

For what glory days were those! The young Miller will have been part of the finance team working to Hanson and his chief accomplice, Gordon White, at their headquarters overlooking Buckingham Palace. It was a company wholly controlled by the two men, insisting on approving every expenditure above £500 by the companies they acquired – even while they pioneered stowing profits in tax havens and raiding pension funds of the companies they took over.

Crucially, Miller will have seen firsthand how Hanson and White stalked their takeover targets, set about winning the battles and then made a fortune from breaking up the victim company while running its core businesses to incredibly stringent financial targets. I have no doubt that, like Hanson and White, both ennobled by Margaret Thatcher who admired them uncritically, he believes in the virtue of what he does. Since founding Melrose, the financial returns have been stratospheric. Miller has yet to be named capitalist of the year by the Times as Hanson was in 1986 – but he is on his way.

But, like Hanson’s, Miller’s is a capitalism organised entirely around extracting rather than creating value. Hanson’s model was brutally simple, exemplified by the 1982 takeover of Berec, the manufacturer of Eveready batteries, and its subsequent breakup – Miller will have had a ringside seat.

Like GKN, it was a proud Midlands-based British engineering company setting about the hazardous business of becoming the international brand leader in batteries, based on high investment in research and development. Who knows? In a different business culture, Berec might now be the world’s leading battery manufacturer, set to exploit the electrification of cars. Instead, it does not exist.

For, like GKN, it made a mis-step – the share price dipped and Hanson launched his bid. The European division was sold off to its chief competitor, Duracell, thus recouping most of the cost of the takeover. Battery prices were increased across the board, so that Eveready quickly lost market share. All new investment could only be justified if the cash was returned in four years while making a 20% return. Ten years later, Eveready had been milked dry, and Hanson sold out to Ralston Purina. Its verdict on Eveready as it assessed its purchase: a company “a number of years behind the times… a business in decline… the whole infrastructure was pretty thin”.

Hanson had made a fortune – but Britain had lost another pivotal company. So it continued. Two years before he left Hanson to found his own Hanson-like shell company, Miller would have been in the thick of the 1986 bid for Imperial Tobacco – then dismembered like Eveready. But the Hanson business model was inherently unstable. To grow and maintain his own share price, he had to go for ever bigger targets to feed the beast. Hanson had an unsuccessful shot at ICI, which saw him off – but only at the price of ICI changing its declared business purpose from bettering society through science to maximising the share price. ICI then broke itself up – but so did Hanson, with the company ignominiously being sold to a German cement company.

We can foretell what will happen to GKN. Businesses will be sold to repay the £8bn. Prices will increase, and market share will be foregone: there is no other option given the millstone of debt around Melrose’s neck. R&D will be frozen at the current levels, already running at half to two thirds the rate of its chief competitors, rendering virtually valueless the promise to the business secretary, Greg Clark, to maintain it. Investment will only be allowed on Hanson-type terms – four-year paybacks and 20% returns. Yes, the company headquarters will remain in Britain – but in Mayfair, not in Redditch. In 10 years’ time, some company will buy the rump of GKN, only to find it in the same condition as Ralston Purina found Eveready.

Melrose’s future is also foretold. For all the hundreds of millions it is making, it will wind up like Hanson. Britain, which already has no major indigenous company in an array of sectors, will have them in even fewer – with all the implications for work, wages, careers and skills. For most of the young analysts at the asset management groups who took the decision to accept Melrose’s offer for GKN, the events I describe will seem like ancient history.

But the same mistakes keep being repeated. To prevent them, the government simply has to rule that only shareholders who own shares at the time of the bid can vote, so disenfranchising the arbitrageurs and hedge funds who swung the decision. But the City establishment lobbies ferociously against this move. For the City is wedded to the value extraction on which its fees depend.

But, like Hanson’s, Miller’s is a capitalism organised entirely around extracting rather than creating value. Hanson’s model was brutally simple, exemplified by the 1982 takeover of Berec, the manufacturer of Eveready batteries, and its subsequent breakup – Miller will have had a ringside seat.

Like GKN, it was a proud Midlands-based British engineering company setting about the hazardous business of becoming the international brand leader in batteries, based on high investment in research and development. Who knows? In a different business culture, Berec might now be the world’s leading battery manufacturer, set to exploit the electrification of cars. Instead, it does not exist.

For, like GKN, it made a mis-step – the share price dipped and Hanson launched his bid. The European division was sold off to its chief competitor, Duracell, thus recouping most of the cost of the takeover. Battery prices were increased across the board, so that Eveready quickly lost market share. All new investment could only be justified if the cash was returned in four years while making a 20% return. Ten years later, Eveready had been milked dry, and Hanson sold out to Ralston Purina. Its verdict on Eveready as it assessed its purchase: a company “a number of years behind the times… a business in decline… the whole infrastructure was pretty thin”.

Hanson had made a fortune – but Britain had lost another pivotal company. So it continued. Two years before he left Hanson to found his own Hanson-like shell company, Miller would have been in the thick of the 1986 bid for Imperial Tobacco – then dismembered like Eveready. But the Hanson business model was inherently unstable. To grow and maintain his own share price, he had to go for ever bigger targets to feed the beast. Hanson had an unsuccessful shot at ICI, which saw him off – but only at the price of ICI changing its declared business purpose from bettering society through science to maximising the share price. ICI then broke itself up – but so did Hanson, with the company ignominiously being sold to a German cement company.

We can foretell what will happen to GKN. Businesses will be sold to repay the £8bn. Prices will increase, and market share will be foregone: there is no other option given the millstone of debt around Melrose’s neck. R&D will be frozen at the current levels, already running at half to two thirds the rate of its chief competitors, rendering virtually valueless the promise to the business secretary, Greg Clark, to maintain it. Investment will only be allowed on Hanson-type terms – four-year paybacks and 20% returns. Yes, the company headquarters will remain in Britain – but in Mayfair, not in Redditch. In 10 years’ time, some company will buy the rump of GKN, only to find it in the same condition as Ralston Purina found Eveready.

Melrose’s future is also foretold. For all the hundreds of millions it is making, it will wind up like Hanson. Britain, which already has no major indigenous company in an array of sectors, will have them in even fewer – with all the implications for work, wages, careers and skills. For most of the young analysts at the asset management groups who took the decision to accept Melrose’s offer for GKN, the events I describe will seem like ancient history.

But the same mistakes keep being repeated. To prevent them, the government simply has to rule that only shareholders who own shares at the time of the bid can vote, so disenfranchising the arbitrageurs and hedge funds who swung the decision. But the City establishment lobbies ferociously against this move. For the City is wedded to the value extraction on which its fees depend.