JFK innings, maestro moments and swaggering slogs, the batsman who made you think: is something brilliant happening?

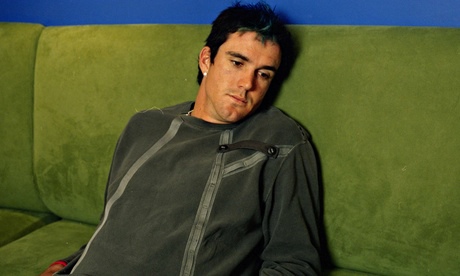

Kevin Pietersen practices his indie-frontman pose for Observer Sport Monthly in 2005. Photograph: Karen Robinson for the Observer

1) The KP moment

There is a delightful scene in the final episode of Nathan Barley, Charlie Brooker's documentary about life at the Guardian. A TV executive has a pint poured over him in the pub and, after reacting with anger, suddenly thinks all might not be what it seems. "Are you guys the crew?" he says, looking round the pub. "Are we all in this? Is something brilliant happening?"

That scene came to mind every time Kevin Pietersen batted. Pietersen was a consistent provider of one of sport's greatest thrills: the sense that something brilliant might be about to happen. Sport is an intrinsically underwhelming experience, such is the chasm between fantasy and reality. Yet Pietersen's Ashes-winning 158, which came so early in his career, established the parameters of his talent – or rather that there were hardly any parameters. The reality of Pietersen did not just match the fantasy; it exceeded it. Not even Walter Mitty could have imagined some of those shots he played.

Every time he was at the crease it was legitimate to think we might be about to witness something epic. And when he got going, it was impossible to contain your excitement. Nobody else made you want to text a friend or rush to the nearest public social-networking house and say excitedly to the nearest person: "Are you watching the cricket? Pietersen's on one here." That's how special Pietersen was: he made you want to talk to strangers.

The excitement of what he might achieve was only half the story. There have been umpteen batsmen with the capacity to dramatically change the population of a bar – emptying them at the ground, filling them in town centres – yet few had Pietersen's combination of omnipotence and fragility. With the obvious exception of Brian Lara, it is hard to think of a batsman with a bigger gap between his top and bottom level of performance. Pietersen could look like Donald Bradman and Phil Tufnell, often in the same innings, sometimes in the same over. He was notoriously nervous at the start of his innings, hence one of his most memorably quirks: the Red Bull single to get off the mark.

With Pietersen, nobody knew anything. You would think you could spot the tell-tale signs that he was going to make a hundred; you'd think you'd visibly see him enter the zone, and two minutes later he'd hook to deep square leg or smack one against the breeze to long-on. Or you'd comment how scratchy he was looking and in the blink of an eye he would be 80 not out and batting like a lord. This, coupled with his mixed popularity and the consequently exaggerated drama of his success and failure, made him the most unputdownable book in sport.

Most of Pietersen's great knocks came after or even during a dodgy spell of form: his Man of the Series performance in England's World T20 win in 2010 was a brief, stratospheric high in the most traumatic year of his career. During the tour of Bangladesh two months earlier, he says he had basically forgotten how to bat and thought his career was in serious jeopardy.

In 2012 he played 17 Test innings in Asia, averaging a modest 39.43. A mediocre year then? Not quite. His scores were 2, 0, 14, 1, 32, 18, 3, 30, 151, 42*, 17, 2, 186, 54, 0, 73, 6 and the two centuries – at Colombo and Mumbai – are the two greatest innings played by an Englishman in Asia. There was a moment in both those centuries when you knew, or you thought you knew, that it was on.

In this age of constant newsflashes, previously reserved for JFK moments, Sky Sports News' yellow ticker should simply have said: BREAKING NEWS: KEVIN PIETERSEN IS BATTING whenever he was at the crease. In sport, JFK moments are supposed to relate to off-field events. We think we know what to expect with the context of the actual sport, so nothing should be so mind-blowing as to become a JFK moment. Yet Pietersen's ability to play with otherworldly genius was such that he became a specialist in JFK innings. Where were you for the 158, the 151, the 149 or the 186?

Within every JFK innings lurked a KP moment, when he did something – a booming drive, a look in his eye, even an ultra-certain defensive stroke – that made you wonder: is something brilliant happening? Whether he succeeded or failed, the answer was usually yes. Pietersen was the point at which sport's three greatest pleasures – partisanship, unpredictability and unimaginable genius – were perfectly in sync.

2) The match-winner

Kevin Pietersen plays a reverse sweep on the third day of the second cricket Test match against Sri Lanka in 2012 Photograph: Eranga Jayawardena/AP

Kevin Pietersen plays a reverse sweep on the third day of the second cricket Test match against Sri Lanka in 2012 Photograph: Eranga Jayawardena/AP

There are lies, bald-faced lies and this statistic: Ian Bell has scored more hundreds in Test victories than any other England batsman, including Kevin Pietersen. Bell is an exquisite talent, whose batting in last summer's Ashes was the finest we have ever seen by an England batsman over an entire series. But to compare him with Pietersen in this sphere is daft. Pietersen did not make hundreds in England victories; he made match-winning hundreds.

At his best, Pietersen's runs were so resounding and symbolic as to make the rest of the game an apparent formality. He was a master of mental disintegration. There was the brutal 227 at Adelaide – without which England would have been 1-0 down going into the final two Tests of the series. There was the six-laden 151 in Colombo in 2012 , the most spectacular catharsis after moments of DRS torment. In that match at Colombo he scored 193 off 193 balls, including eight sixes, and was out once. So an average of 193 and a strike rate of 100. The other 21 players averaged 29 and scored at a strike rate of 40.

It was not just that Pietersen did things mere mortals could not; he did things that were beyond his fellow immortals. Very few batsmen in history could have played Pietersen's true masterpiece, the reintegration 186 at Mumbai. That was deemed the fourth-best Test innings of all time in the book Masterly Batting, the most forensic study of the greatest Test innings that we have come across. (Yes we did write an essay for the book but that's not the point.)

Pietersen had three innings in the top 100 of that book; only Don Bradman, Brian Lara, Graham Gooch and Gordon Greenidge had more. Since Lara retired, nobody has played as many epics as Pietersen. There is also the weirdly underrated 142 in a low-scoring match at Edgbaston in 2006 (nobody else scored more than 30 in the first innings), when he switch-hit Muttiah Muralitharan for six. There was the Ashes 158, which did not win a match but did win a mildly important series, and our personal favourite, the 149 against South Africa at Headingley on Super Saturday of the Olympics. Trust Pietersen to rise to the big occasion.

In the last couple of years we have seen the development of a dubious, almost smug cliché that Pietersen is a player of great innings rather than a great player. Pietersen's overall record stands up extremely well – his Test average of 47.28 is the highest by an England batsman since Geoff Boycott retired in 1982 – but far more significant are two things not recorded in Wisden: the number of neck hairs he had made stand to attention, and the impact his runs have had.

Let's be clear about this. Without Pietersen, England would not have won the Ashes in 2005 and might not have won them in 2010-11; they would not have won their first Test in Sri Lanka for 11 years; they probably would not have won in India in 2012-13 or triumphed in the World T20 in 2010. Pietersen played a series of exceptional innings that won things for his team and took out a lease in the memory bank. If that's not greatness, then we're not sure what is.

3) The skunk punk

Kevin Pietersen acknowledges the applause of the Oval crowd as he walks off having scored 158 runs during the final day of the fifth test of the 2005 Ashes series. Photograph: Kieran Doherty / Reuters/Reuters

Kevin Pietersen acknowledges the applause of the Oval crowd as he walks off having scored 158 runs during the final day of the fifth test of the 2005 Ashes series. Photograph: Kieran Doherty / Reuters/Reuters

The legend of Kevin Pietersen's life-changing innings is told thus: the greatest Ashes series of all time was at stake, England needed to bat for a draw, and this daft bugger went on a demented joyride! That is how we will remember his Ashes-winning 158 at The Oval on 12 September 2005. There was actually a little more to it than that. Pietersen played four innings in one day, two of them at the same time. Before lunch he was nervous and unsure of how to play; he was a punchbag for Brett Lee and fortunate to survive two dropped chances. Between lunch and tea, he marmalised Lee and Shaun Tait while blocking Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne. And after tea, with the Ashes won, he let his skunk down and had some fun against all-comers.

At lunch England were 127 for five, a lead of 133 with a possible 64 overs remaining. There wasn't a dry nail in the house. It's still a little chilling to reflect how close England were to not winning the Ashes. Pietersen was 35 from 60 balls. He had played scratchily apart from two defiant slog-swept sixes in one Warne over. The story goes that, after a chat with his captain Michael Vaughan, he simply decided "To hell with it" and went after everything that moved. In fact the innings was far subtler.

Warne and Lee continued after lunch. Pietersen launched into Lee, flogging him for a staggering 35 from 13 balls, including two hooked sixes and four fours. Lee's bowling peaked at 96.7mph – notably faster than Mitchell Johnson right now – yet Pietersen took on almost every delivery.

All the while, at the other end, he milked Warne clear-headedly. When Lee was replaced by McGrath, Pietersen pressed the stop button. England scored 19 from the next 11 overs, all bowled by the two champions, before Ricky Ponting replaced McGrath with Tait. The first two balls were flogged for four and in the next half an hour Pietersen savaged Tait for 22 from 12 balls. By tea, the Ashes were all but won. In that decisive session, Pietersen took Lee and Tait for 57 off 25 balls at a strike-rate of 228 runs per 100 balls. Off Warne and McGrath he scored 13 from 41 balls at a strike rate of 32. He had a first gear, a tenth gear and nothing in between. Not bad for someone who can only play one way.

This is not to say Pietersen could not give McGrath and Warne tap. In his first Test innings at Lord's he carted McGrath back over his head for an absurd six born of the most magnificent disrespect, and he spent the summer slog-sweeping his mate Warne into the crowd at midwicket (as well as being dismissed by him on a few occasions). Those slog sweeps are perhaps the most memorable feature of Pietersen's first summer as a Test cricketer, not least because it was a shot he eschewed as time went on. (It made a brief and wonderful comeback during his Mumbai maestropiece in 2012.)

Pietersen became a far better batsman than he was in 2005: technically tighter, more complete, more mature, a lot more accomplished on the off side. He even managed to overcome the nervous 158s. Yet though he remained one of the most entertaining batsman around, he never had quite the same exhilarating skunk punk edge of his first year in international cricket. In that time he also made those three one-day hundreds in South Africa and hammered Jason Gillespie into the knackers' yard in an ODI at Bristol, after which his captain Vaughan became the first significant person to use the G-word. Andrew Flintoff recalls Pietersen sitting in the dressing-room saying "Not bad am I?"

Not bad at all for a man who five years earlier was a tail-end slogger called Pieterson. After 10 ODI innings in 2004-05, his average was 162.25. As with the Prodigy's Experience, Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets and Michael van Gerwen in the second half of 2012, this was a raw, visceral introduction that would eventually become only a small part of a complete body of work. But that subsequent maturity partially obscures just how incredibly fresh and exciting he was in his first year. Pietersen, for richer and poorer, was never the same batsman after 2005. And although he played better innings than the 158, it was his career-defining performance.

4) The pace batsman

Kevin Pietersen mauls South Africa during the World Twenty20 tournament in 2010. Photograph: Julian Herbert/Getty Images

Kevin Pietersen mauls South Africa during the World Twenty20 tournament in 2010. Photograph: Julian Herbert/Getty Images

Kevin Pietersen was a pace batsman. Not in the sense that he scored his runs quickly, but that he thrillingly reversed the traditional relationship between fast bowler and batsman, hunter and hunted, intimidating opponents with his size and aggression. He followed in the swaggering footsteps of Viv Richards, Matthew Hayden and others by playing the batsman as physical bully. Sometimes he even gave the fast bowlers some chin music of their own, belabouring life-threatening straight drives.

Three particular innings stand out. At the Oval in 2005 he drowned Brett Lee and Shaun Tait in their own adrenaline; he played Tarzan cricket against Morne Morkel and Dale Steyn at the World T20, mauling Steyn for 23 from 8 balls – including a flamingo shot to the offside - and sent an unprecedented shiver down Mike Selvey's spine; and at Headingley in 2012 he played the most otherworldly innings the Joy of Six has ever seen, when he was obviously in the zone that he should have had a forcefield around him.

Pietersen loved taking on the spinners, he loved to prove his technical class with off- and on-drives. But nothing stimulated him quite like the chance to assert his alpha-male status via the medium of pummelling 95mph deliveries all round the park. And nothing stimulated us the same way either.

5) The dumbslog millionaire

A dejected Kevin Pietersen leaves the field after being dimissed on 97 during the first day of the first Test match against West Indies at Sabina Park. Photograph: Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images

A dejected Kevin Pietersen leaves the field after being dimissed on 97 during the first day of the first Test match against West Indies at Sabina Park. Photograph: Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images

Kevin Pietersen took 183 Test wickets. Ten with the ball, and 173 with his own bat. To explain: it is hard to recall a batsman whose dismissals brought such focus – not just because they were an event, but because they were always his fault. Pietersen never got a good ball in his career. He was never got out. He always got himself out.

It's true that there were plenty of notorious shots. The dumbslog millionaire incident in Jamaica 2009, and a similar dismissal against South Africa at Edgbaston a year earlier. (Both times he was trying to reach a hundred with a six. Pietersen often could not resist going to a hundred on his terms: he did so with a reverse sweep in the 2012 epics at Colombo and Mumbai.) There was the lap sweep off Nathan Hauritz at Cardiff in 2009, and plenty of flat-footed wafts or pulls straight to long leg or deep-square leg.

Sometimes his confidence could backfire comically. In 2006 he said there was simply no way he could be bowled round his legs by Shane Warne; guess what dismissal catalysed the miracle of Adelaide. The same winter, Pietersen treated an ageing Glenn McGrath with disdain, walking down the wicket repeatedly during the one-dayers. McGrath broke his ribs with a bouncer.

It does nonetheless feel that Pietersen dismissals invited disproportionate opprobrium. While he found many weird and wonderful ways to get out in Australia last winter, for example, so did Ian Bell. Bell dragged a full toss from a part-time spinner to midwicket; he drove his first ball straight to mid-off; he played a late cut straight to gully. Hardly a word was said.

The idea that Pietersen couldn't care less about the team was not fair. For one thing he knew, from the moment he made that 158 against Australia, that individual glory was multiplied tenfold when it facilitated team glory. And he often knuckled down. In that 158 at The Oval he played like Chris Tavare and Viv Richards at the same time, while his tone-setting double-century against India at Lord's 2011 – an innings whose brilliance has been obscured by the 4-0 mauling that it set up - was a masterpiece of moving through the gears as conditions get easier: his four fifties respectively took 134 balls, then 82,85 and 25.

There's no question that Pietersen was occasionally driven to excessive stubborn, hiding behind the catch-all phrase "That's the way I play". Yet there was an essential truth in that. The poor strokes were inextricably linked to the outrageous shots; both came from the instinctive, often flawed shot selection that also allowed him to play innings of staggering genius. It borders on infantile to celebrate the audacious shots and chastise the cheap dismissals. Dolly Parton and David Brent would have understood Pietersen.

Pietersen had to do things on his terms; without that he was nothing. To criticise him for a poor shot is like moaning about an ecstasy comedown or a broken heart at the end of the best relationship of your life. It may be a simple case of English suspicion of unusual talent, the same that manifested itself when David Gower wafted lazily to slip. In this country, certain types of dismissals are morally acceptable. This is not to absolve Pietersen of all blame. No man can bat with impunity. Yet as with Gower there seemed to be a damaging desire to mould Pietersen into something he could never be. He had to play it as he saw it. And he saw cricket through different eyes to normal human beings.

Those eyes allowed him to conceive and play some of the most extraordinary strokes. He took advantage of the possibilities afforded Test batsmen first by Steve Waugh and then by Twenty20. The established norms and mores of five-day cricket have been shattered, as has the coaching manual. Just as language has never been more flexible and exciting, nor has Test batting. Pietersen developed his own urban coaching manual, full of unique and totally modern shots.

The most celebrated, the switch hit, never really got the Joy of Six going: it was brilliant and audacious but not unique. Far more spine-tingling were the established, conventional shots that Pietersen remixed. The flick through midwicket, with added flamingo; the straight drive played wristily and on the run; and our favourite, this dreamy slow-motion pull off Dale Steyn.

In an interview with All Out Cricket last year, Pietersen picked out that and anotherdreamy swipe off Pragyan Ojha at Mumbai as his favourite shots. "The slowness of my bat speed through those balls is what stands out to me," he said. "I look at those two shots – and I don't normally like to talk about my shots – but I do occasionally look at those and go, 'How the hell did you do that?' I don't know …"

Some things are best left unexplained.

6a) The dressing-room influence

England's Alastair Cook and Kevin Pietersen look-on from the dressing room balcony during day four of the third Test at the WACA on 16 December, 2013. Photograph: Anthony Devlin/PA

England's Alastair Cook and Kevin Pietersen look-on from the dressing room balcony during day four of the third Test at the WACA on 16 December, 2013. Photograph: Anthony Devlin/PA

In 2012, the sarcastic air violins came out when Kevin Pietersen said: "It's not easy being me in that dressing-room." In fact it's the most undeniable thing he's ever said. For much of his nine-and-a-bit years in international cricket It was clearly not easy being Pietersen in the England dressing-room; the only thing worthy of debate is whose fault that was.

There have been tedious assumptions about who did what to prompt Pietersen's sacking. The principal emotion should be sadness, not anger. It is wrong to assume that England need to give a specific example of Pietersen's behaviour, or even that there is a specific example; often it's an accumulation of incidents that create a sense that is not easy to articulate. Pick the person you most dislike at work and then try to explain to an outsider why that is so. It doesn't look nearly as powerful on the page as it is in your head. The same is probably true of England's intractable conviction that Pietersen was a damaging dressing-room influence.

It's insulting to suggest that this was a decision taken on a whim, because Alastair Cook, Paul Downton and the rest didn't fancy the hassle. The fact we have seen this storyline played out so many times before suggests Pietersen cannot be entirely innocent. It is probably a failure of management to some extent, but then there is always a point at which something becomes unmanageable. There is always something beyond the pale.

That doesn't mean the decision was necessarily fair on Pietersen. He will argue that his problems on the recent Ashes tour, and with Peter Moores, came from nothing more than a desire for excellence and an abhorrence of mediocrity that was too much for weak minds. It would be extremely unwise to assume that just because Pietersen is in a minority, he is intrinsically wrong; there are umpteen historical examples, in far more important walks of life of sport, that remind us of that.

In an age of passive-aggressive manipulation, there is something refreshing about Pietersen apparently wanting to have things out in the open with his team-mates (even if, when it comes to briefing and PR, he is as disappointingly snide as the rest). He might also argue that England had no problems with him when they were winning and he was scoring monstrous centuries. It's legitimate to wonder how this England team might have coped with Sir Ian Botham and Shane Warne. The key point is that we simply don't know; at best we are making uneducated guesses.

The relationship between the England team and Pietersen was often described as a marriage of convenience yet in a sense they were more like acquaintances with benefits. We should have known it was going to end like this.

6b) The conversation-starter

Kevin Pietersen acknowledges the crowd during England's 2005 Ashes celebrations. Photograph: Tom Jenkins for the Guardian

Kevin Pietersen acknowledges the crowd during England's 2005 Ashes celebrations. Photograph: Tom Jenkins for the Guardian

Never mind the dressing-room; it was not easy being Pietersen out in the middle. Sometimes it was his sanctuary, other times he batted under unimaginable pressure. Sachin Tendulkar batted with the hopes of millions of India on his shoulders – but at least they all wanted him to succeed. Pietersen batted knowing that 50% of Englishmen were desperate for him to succeed and 50% even more desperate for him to fail. Sometimes he even had to play against two teams, as during his astonishing 149 against South Africa and England at Headingley in 2012.

It's often said that Pietersen batted for himself; as his career went on, he had little choice but to do that, so isolated did he become. Which is the chicken and which is the egg in this situation will be forever debated. Either way, he had to bat knowing that, whatever happened, he would be the watercooler's hottest topic afterwards.

He had a unique burden. He had to hit sixes but not get out trying to hit sixes. He had to counter-attack but not get out counter-attacking. In the 2007 World Cup, England needed him to be pinch-hitter, anchor and death-hitter all in one. It was an absurd burden.

That, coupled with his perpetual sense – fair or not – of being misunderstood and unloved, makes you wonder just what he would have achieved with unconditional love. Sometimes the awkwardness made him bat better. Unpopularity can be the most powerful fuel of all, but only in the short-term, unless you are a WWF wrestler. Over time it will have weighed heavily both on his conscious and unconscious.

The phrase "We need to talk about Kevin" quickly became a boring cliché. It arguably missed the point. We didn't just need to talk about Kevin because of what Kevin did, as in the film; we needed to talk about Kevin whether he did anything or not, because he enlivened our grubby, boring lives. He brought out the village gossip in us all. He was so charismatic that we became addicted to him, so we discussed things that we would not with other players. Our lives will be significantly duller without him.

No comments:

Post a Comment