'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 23 May 2021

Thursday, 20 May 2021

How Sadhguru built his Isha empire. Illegally

Anish Daolagupu

Jaggi Vasudev, Anglophone India’s star godman, has challenged on more occasions than one that if the accusations of illegal deeds that have followed him around like ardent devotees were ever proved, he would quit India. The charges are legion, contained in testimonies of the allegedly wronged and tomes of government records. And there is much there, as Newslaundry found after examining a whole lot of them, to, at the very least, merit an investigation. Absent that, the accusations remain just that, accusations, merely a nuisance in his way as Vasudev goes about expanding his vast religio-cultural and business empire, the Isha Foundation. And, in the process, building himself up as arguably the country’s most influential godman.

But what precisely are the accusations against Vasudev, or Sadhguru as his devotees know him? Have they ever been investigated? If yes, what was the outcome? If no, why not? Did he use his godman persona and influence to indulge in illegalities or did the alleged illegalities enable his rise to fame and fortune?

To answer such questions, Newslaundry spoke with public servants, activists, and whistleblowers; trawled government records on the foundation; and examined court cases filed against them over the years and investigations conducted.

What we pieced together is really just the same old story of greed, corruption, and abuse of socio-religio-cultural sentiment for material enrichment. At the centre of this story is an Adivasi hamlet called Ikkarai Boluvampatti in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore.

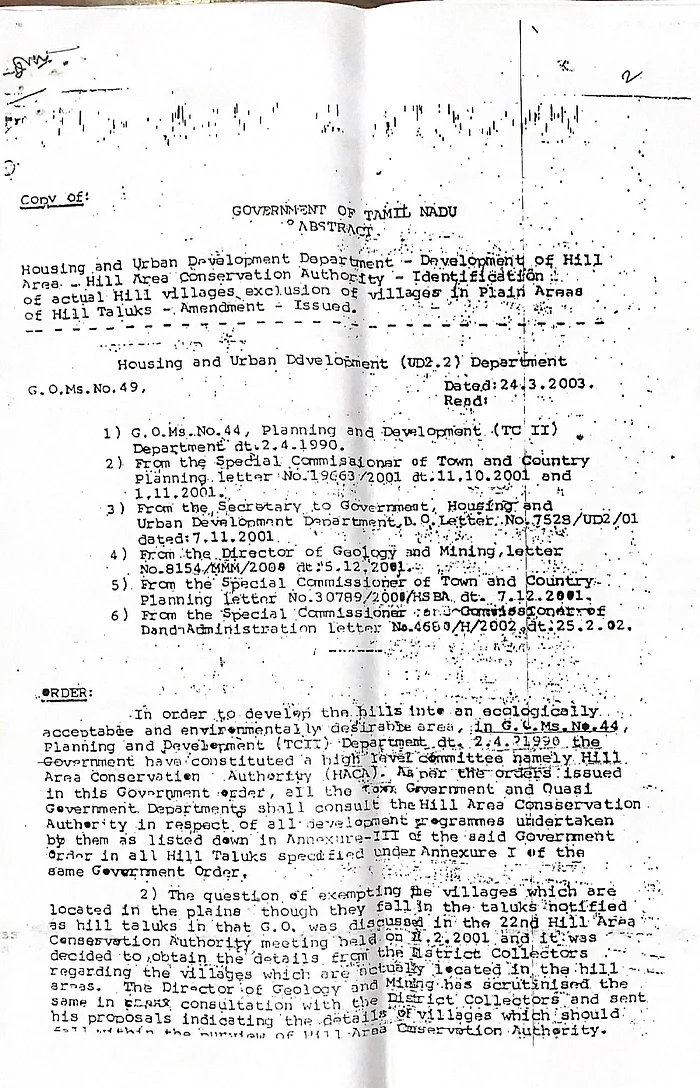

Ikkarai Boluvampatti, in the foothills of the Velliangiri hills, is where the Isha Foundation is headquartered on a sprawling 150-acre campus of 77 large and small structures, including the Isha ashram, built between 1994 and 2011 in blatant violation of laws and rules. The campus is adjacent to the Bolampatty Reserve Forest, an elephant habitat in the Nilgiris biosphere reserve, and along the Thanikandi-Marudhamalai migration corridor of the pachyderms. So, human activity, let alone construction, is regulated by the Hill Area Conservation Authority, or HACA, set up in 1990 to preserve wildlife and ecology of forested hill regions of Tamil Nadu.

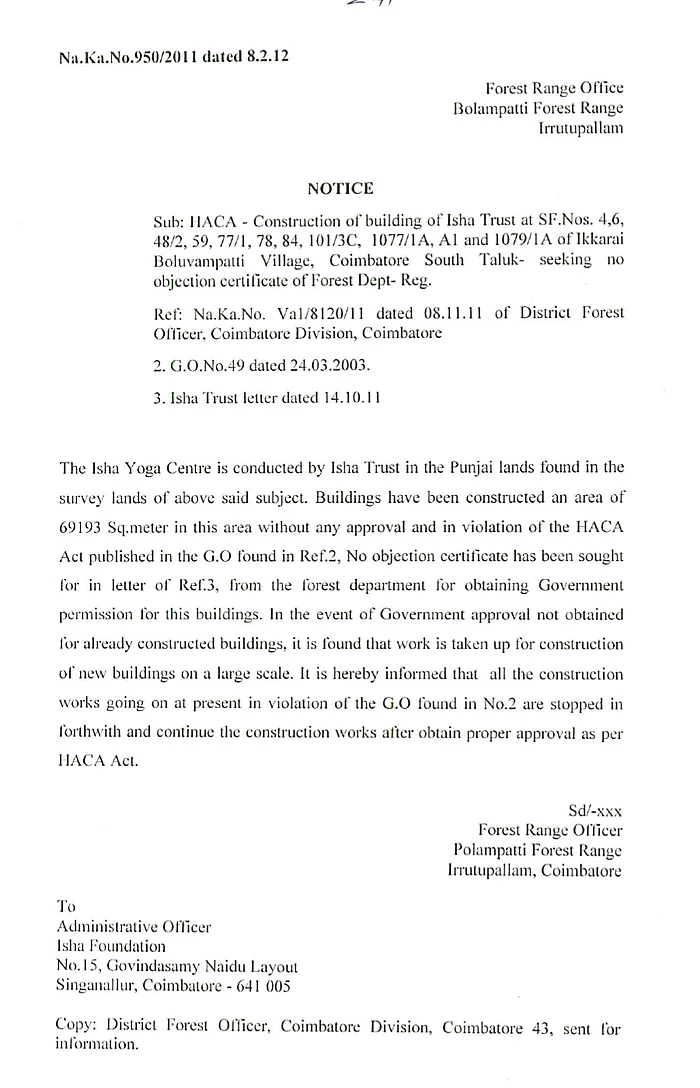

Here, construction on over 300 sq metres of land can’t be done without HACA’s approval. Yet, records obtained by Newslaundry from the state departments of forest, town and country planning, and housing and urban development show that from 1994 to 2011, Isha constructed on 63,380 sq meters and created an artificial lake on another 1,406.62 sq metres at Ikkarai Boluvampatti, without approval. Vasudev and his foundation have said they got permission to build on about 32,855 sq metres from the local panchayat, but the rural body doesn’t have the power to authorise construction in areas under HACA.

Isha did apply for approval from HACA in 2011, but after they had already built several structures. In July 2011, a forest department document shows, Isha asked HACA to greenlight illegal constructions on 63,380 sq meters as well as new constructions on 28582.52 sq metres. Taking up the application, V Thirunavukkarasu, then Coimbatore’s forest officer, visited the Isha ashram in February 2012. He found Isha had illegally constructed a series of buildings, including on the 28,582.52 sq meter plot for which it had gone to HACA for approval.

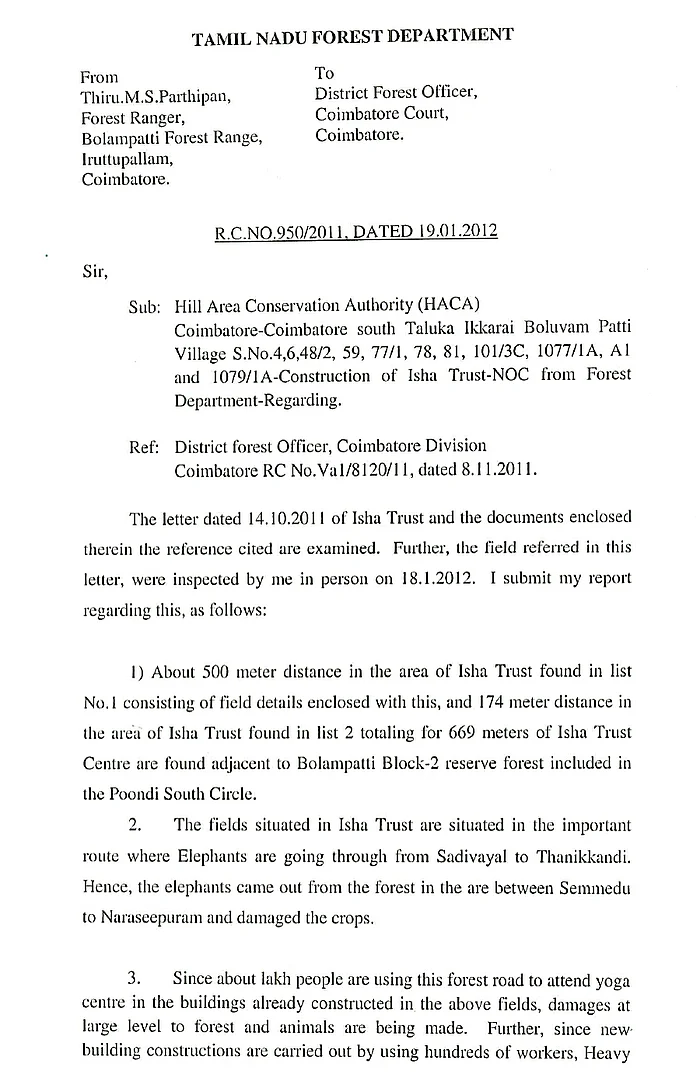

Thirunavukkarasu also found that the compound wall of the ashram and front gate were built from the forest land. Moreover, Isha’s many constructions and the resultant rush of visitors to the ashram had obstructed the elephant corridor, heightening man-animal conflict. So, he denied them approval. In October that year, Isha withdrew its application on the prexet of amending it. They didn’t file it again until 2014.

Thirunavukkarasu would return to Coimbatore as the chief conservator of forests in 2018, only to be moved out after just four days.

MS Parthipan, a forest ranger, too visited the Isha ashram in 2012. He found some of its lands fell on routes elephants used to move between Sadivayal and Thanikkandi. Since Isha had illegally erected buildings, walls and electric fences on these lands, elephants were forced to emerge from the forest between Semmedu and Narseepuram, trampling crops and attacking villagers.

“Any construction requiring over 300 sq meters of land requires HACA’s permission. Isha undertook construction without permission over a large area. They built structures first and then applied for approval. Whenever they did seek permission for new construction, they didn’t wait for our nod and simply started building,” a forest official who was privy to Parthipan’s inspection said on the condition of anonymity. “Isha’s lands were inside the elephant corridor and they were obstructing it, so they didn’t get clearance.”

Isha has marked at least 33 structures at the Ikkarai Boluvampatti campus for religious use which means they are considered public buildings under Tamil Nadu’s planning rules. Such structures require approvals from the district collector and the deputy director for town and country planning to build. Isha, records from the housing and urban development department show, didn’t bother taking these approvals.

Instead, they went to the panchayat, which isn’t empowered to grant such permissions without consulting the town and country planning department. The foundation did eventually go to the planning department for approval in 2011, but only after they had erected a series of structures – illegally. Aside from seeking approval for what they had built over the previous 15 years, the foundation asked the planning department for permission to construct 27 new buildings. The application, however, was incomplete and the department told them to file a new one by February 2012.

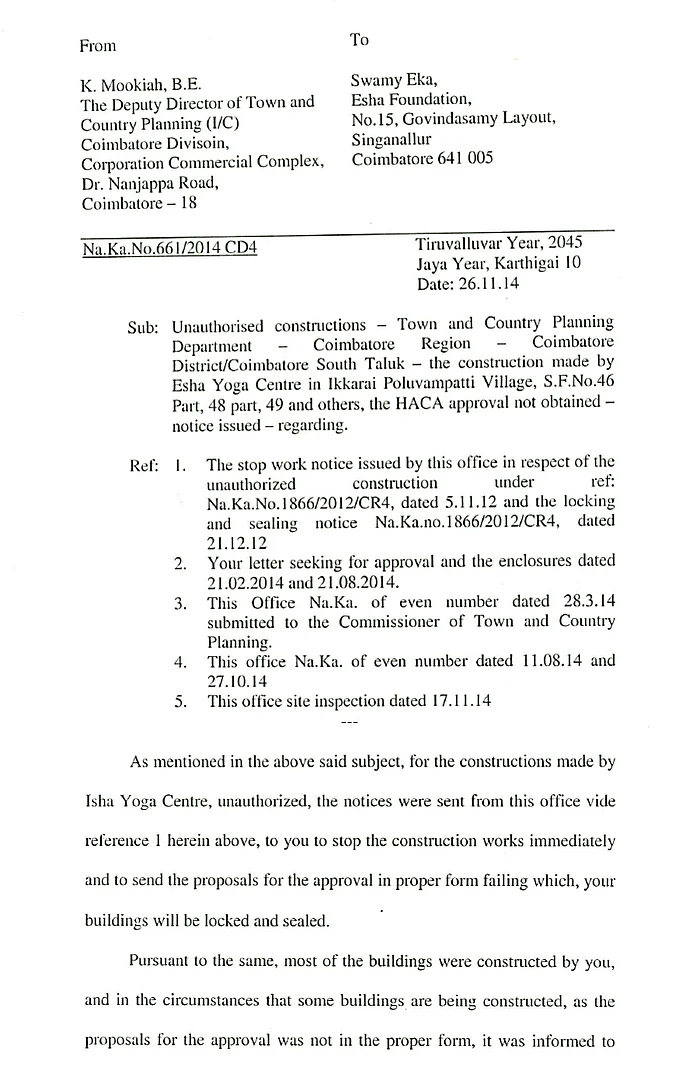

Isha breached the deadline and only sent a new application seven months later. Subsequently, when planning officials visited the ashram in October 2012 they found construction of the new buildings had already begun. They ordered the foundation to immediately stop all construction and followed up with a notice in November 2012. Isha didn’t care.

Finally, in December 2012, the planning department sent another notice directing Isha to demolish all illegal structures within a month. The foundation challenged the notice before the town and country planning commissioner. The matter is still hanging fire.

At the time, K Mookiah was deputy director, the town and country planning department, Coimbatore. Why did his department not act against Isha when they disregarded its orders? “After a month of issuing the notice I was transferred out,” he replied. “I don’t know what happened after that. I don’t know whether they have taken the approval or not.”

By 2012, Isha had constructed as many as 50 structures and was building 27 more, all illegally.

The foundation’s illegalities didn’t go unchallenged.

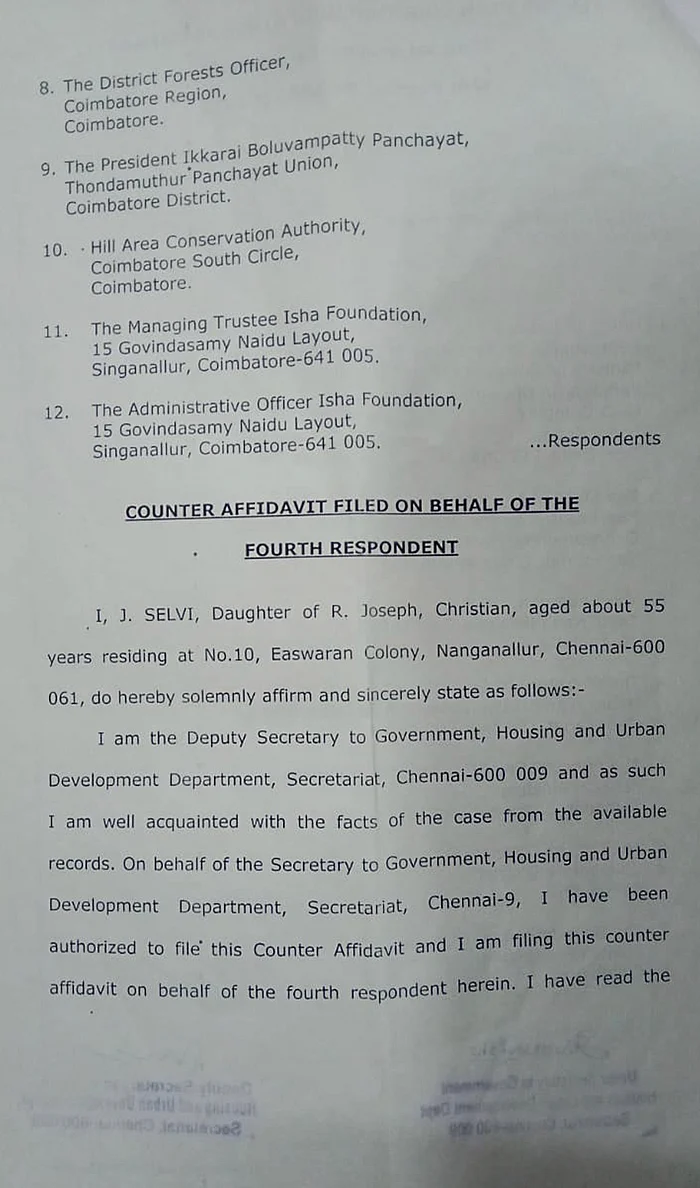

For the past eight years, M Vetri Selvan of the NGO Poovulagin Nanbargal has been fighting against Vasudev’s illegal constructions in the Madras high court, where he filed four petitions in 2013 and 2014. In his pleas, Selvan asked that the planning department’s order for demolition of Isha’s illegal structures be carried out, officials who had not acted against its illegalities be punished, Isha Sanskriti School’s illegal operation be stopped, and provision of cheap electricity to the Isha campus be stopped.

The pleas saw a total of 10 hearings from March 2013 to April 2014. And none since. “Our first petition regarding the demolition of Isha’s illegal construction was heard on March 8, 2013. A notice was issued to Isha, district collector, forest department, HACA, village panchayat. At the next hearing on March 25, 2013, Isha’s advocate sought time to file a counter.

On June 20, Isha, the planning department and the state government all filed their responses and the matter was adjourned. On August 22, 2013, we filed three more petitions and a combined hearing on all four pleas took place the next day. Both sides made arguments, but there was no reply from the state government and the matter was adjourned again,” he said. “At a hearing on March 13, 2014, the state school authority submitted that they hadn’t given Isha permission to run a school. After that, the court said the final hearing would happen once all the respondents had filed their counters. There has been no hearing since.”

In 2017, Selvan filed a petition against Isha’s Mahashivratri celebration, but the court didn’t entertain it because his previous pleas were still pending.

“The court also said I’d filed the petition with ulterior motive,” he added. “Man-animal conflict in and around the forests of Coimbatore has seen a spurt in the past 15-20 years. Primary reason is illegal construction in the elephant habitat, and Isha is involved on a wide scale. We are trying to save the natural environment of this area, to preserve its biodiversity. That’s why we are fighting against Isha’s illegal constructions. It’s not a personal feud.”

Isha's Adiyogi statue.

After he was turned away by the high court, Selvan went to the National Green Tribunal against Isha’s “destruction of environment and wildlife”. Three years later, the NGT directed Isha and the local administration to ensure big functions at the ashram such as the Mahashivratri celebration didn’t cause pollution.

Selvan wasn’t alone knocking the high court’s doors with a complaint against Isha in 2017. The Velliangiri Hill Tribal Protection Society also filed a plea, through P Muthammal, 49, an Adivasi from the Muttathu Ayal settlement in Ikkarai Boluvampatti.

Muthammal pleaded that rising man-animal conflict, for which Isha’s illegal constructions were mainly to blame, had made the lives of Adivasis difficult. He also objected to the foundation’s 112-foot Adiyogi statue, noting that it had been built without necessary clearances.

Replying to the petition, R Selvaraj, then deputy director, town and country planning, confirmed that the statue had been built without his department’s approval.

But by the time Selvaraj filed the reply, on February 28, 2017, the statue had already been inaugurated by none less than the prime minister.

That Modi didn’t hesitate to inaugurate the statue even though it was mired in a legal challenge was telling. A key reason Isha has got away with blatantly violating rules is that it has been enabled by political authorities, particularly the Tamil Nadu government.

Most blatantly, the forest department has dramatically changed its view that the Isha ashram is situated in the elephant corridor.

In 2012, records seen by Newslaundry show, Coimbatore’s forest officer told the state’s principal chief conservator of forests that Isha had built on land in the elephant corridor and its constructions and the rush of the devotees to the ashram – nearly two lakh on on Mahashivratri alone – had heightened man-animal conflict. Installation of powerful lights and high-decibel audio, not least for the Mahashivratri celebration, had only worsened the situation.

Similarly, a 2013 notification issued by the district collector stated in no uncertain terms, though without naming Isha, that illegal construction near the reserve forest in Ikkarai Boluvampatti was increasingly obstructing the corridor for elephants, causing the animals to damage life and property. The notice threatened to cut power, water ,sealing and demolition of the premises which had been built without HACA’s approval.

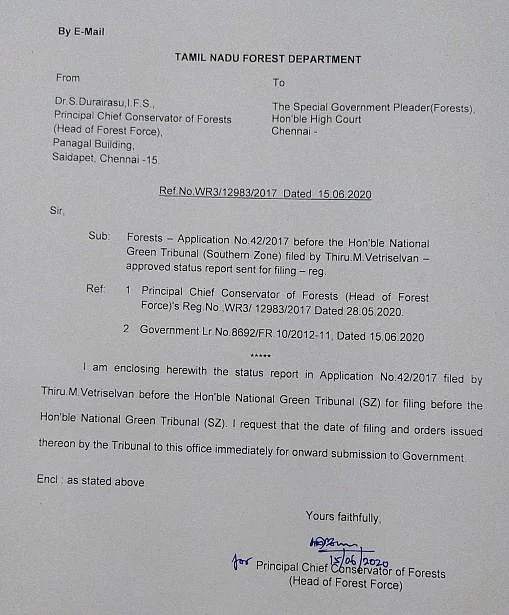

By 2020, however, the forest authorities were singing a discordant tune. In a June 2020 status report submitted to the National Green Tribunal, principal chief conservator of forests P Durairasu, claimed that the Isha campus was “adjacent” to the Ikkarai Boluvampatti Block 2 reserve forest, which was a “famous elephant habitat” but not a designated elephant corridor. For their yearly migration, he added, elephants passed near where the Isha ashram was situated in Ikkarai Boluvampatti but this spot wasn’t an authorised elephant corridor.

The swing in the forest department’s position on Ikkarai Boluvampatti would prove conveniently beneficial for Isha. In March last year, the EK Palaniswami government directed the regularisation of plots which have been built on without approval in the hill areas, including HACA lands that supposedly do not fall within the elephant corridor. They include Ikkarai Boluvampatti.

“We believe this rule has been brought to indirectly help the Isha Foundation regularise its illegal constructions,” claimed G Sundarrajan, an activist with the environmental advocacy group Poovulagin Nanbargal. “The government hasn’t yet notified they have made this rule.”

In 2017, after Isha had applied for HACA approval for constructions that they had already erected, H Basavraju, then the principal chief conservator, set up a committee to examine the submission. The committee found that Isha’s constructions were damaging to local wildlife and environment, and asked the district forest officer to recommend post-construction approval only if Isha made changes to the buildings, stopped using a few roads and agreed to not make any new construction within 100 metres of the forest reserve.

The same year, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India pulled up the state’s forest department for not stopping Isha’s illegal constructions despite knowing about them since 2012. The constructions had been done without required approvals from HACA, the CAG reiterated.

Responding to the CAG’s report, Isha claimed they have received HACA approval for all their constructions on March 16, 2017. But the committee formed by the principal chief conservator to inspect the Isha campus and decide on its application was formed only on March 17, and submitted its report on March 29. In fact, it wasn’t until April 4 that the principal chief conservator made a conditional recommendation to the town and country planning to grant post-construction approval to Isha. The planning department, in turn, directed its regional deputy director in Coimbatore on May 3 to issue post-construction to Isha provided they paid the required fees and adhered to the conditions of the forest department. How then is it possible for the HACA to have approved Isha’s constructions on March 16?

Isha refused to respond to this and other specific allegations. Replying to an email by Newslaundry seeking comment, a spokesperson for the foundation warned, “While your assumptions and presumptions are not material to us, should you slander the foundation, you will do so at your own risk.”

Tamil Nadu doesn’t have a mechanism to give post-construction clearance. The town and country planning department can regularise a construction post facto but only if its conditions are met. It can’t give an environmental clearance, however.

Basavraju, principal chief conservator at the time, wouldn’t answer our questions about recommending post-construction approval for Isha’s structures. His successor, Durairasu, who filed the status report to the National Green Tribunal, said, “Conditions were levied and then only recommendations were made. I don’t know whether they followed the conditions. As per my knowledge they have not received permission from HACA until now.”

Rajamani, who as Coimbatore’s district collector heads HACA, said he didn’t want to talk about the agency’s approval to Isha. “You can write whatever you want,” he added.

The secret of Johnson’s success lies in his break with Treasury dominance

Gordon Brown’s rule-based approach shaped Whitehall for two decades. But the Tories are forging a new politics that has little regard for prudence writes William Davies in The Guardian

Illustration: Eva Bee/The Guardian Thu 20 May 2021 07.00 BST

The Conservative party’s growing electoral dominance in non-metropolitan England, so starkly re-emphasised by results in the north-east, has been attributed to various causes. Brexit and the popularity of Boris Johnson both count for a great deal. But while Labour is busy telling voters how much it deserved to lose, this is only half the picture. A major part of Johnson’s appeal is the way he has escaped the shadow cast by one of Britain’s three most significant political figures of the past 45 years: not Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair, but Gordon Brown.

The 1994 meeting between Blair and Brown at the Granita restaurant in Islington, north London, shortly after John Smith’s death, is the founding myth of New Labour: the moment when Brown agreed to let Blair stand for the leadership, on certain conditions. In addition to Blair’s much disputed commitment to serve only two terms in office should he become prime minister, there was also his promise that Brown, as chancellor, would get control over the domestic policy agenda. At least the second of these commitments was honoured, resulting in a situation where, from 1997 to 2007, the Treasury held an overwhelming dominance over the rest of Whitehall, while Brown was implicitly unsackable.

But, together with his adviser Ed Balls, Brown was also the architect of a new apparatus of economic policymaking designed for the era of globalisation. The central problem that Balls and Brown confronted was how to build the capacity for higher levels of social spending, while also retaining financial credibility in an age of far more mobile capital than any confronted by previous Labour governments. The fear was that, with financial capital able to cross borders at speed, a high-spending government might be viewed suspiciously by investors and lenders, making it harder for the state to borrow cheaply. The first part of their answer endures to this day: operational independence was handed to the Bank of England, accompanied by an inflation target. No longer could politicians seek to win elections by cutting interest rates, a move that aimed to win the trust of the markets.

On top of this, Brown also introduced a culture of almost obsessive fiscal discipline, as if the bond markets would attack the moment he showed any flexibility – the same paranoia that shaped Clintonism. His “golden rule”, outlined in his first budget, stated that, over the economic cycle, the government could borrow only to invest, not for day-to-day spending. The Treasury governed the rest of Whitehall according to a strict economic rubric, demanding every spending proposal was audited according to orthodox neoclassical economics.

Balls later wrote that their thinking had been guided by an influential 1977 article, Rules Rather than Discretion, in which two economists, Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott, sought to demonstrate that policymakers will produce far better economic outcomes if they stick rigidly to certain principles and heuristics of policy, rather than seeking to intervene on a case-by-case basis. Brown’s robotic persona and his mantra of “prudence” conveyed a programme that was so focused on policy as to be oblivious to more frivolous aspects of politics.

Elements of this Brownite machine remained in place during the David Cameron-George Osborne years: a chancellor acting as a kind of parallel prime minister, transforming society through force of cost-benefit analysis, only now the fiscal tide was going out rather than in. Even “Spreadsheet Phil” Hammond sustained the template as far as he could, in the face of ever-rising attacks from the Brexit extremists in his own party. The point is that, from 1997 to 2019, the government largely meant the Treasury. Those powers that are so foundational for the modern nation state – to tax, borrow and spend – were the basis on which governments asked to be judged, by voters and financial markets.

Various things have happened to weaken the Treasury’s political authority over the past five years, though – significantly – none of these has yet seemed to weaken the government’s credibility in the eyes of the markets. First, there was the notorious cooked Brexit forecast published in May 2016, predicting an immediate recession, half a million job losses and a house price crash, should Britain vote to leave. The referendum itself, a mass refusal to view the world in terms of macroeconomics, meant there could be no going back to a world in which politics was dominated by economists.

Consider how different things are now from in Brown’s heyday. Johnson’s first chancellor, Sajid Javid, lasted little more than six months in the job, resigning after one of his aides was sacked by Dominic Cummings without his knowledge. His second, Rishi Sunak, may have high political ambitions and approval ratings, but scarcely forms the kind of double-act with Johnson that Brown did with Blair, or Osborne with Cameron. Johnson’s cabinet is notable for lacking any obvious next-in-line leader.

What’s more interesting are the parts of Whitehall that have suddenly risen in profile under Johnson: communities and local government under Robert Jenrick, and the Department for Digital, Culture Media and Sport under Oliver Dowden. With the “levelling up” agenda of the former, (manifest in such pork barrel politics as the Towns Fund) and the “culture war” agenda of the latter (evident in attacks on the autonomy of museums), a new vision of government is emerging, one that is no longer afraid of expressing cultural favouritism or fixing deals. Balls and Brown were inspired by “rules rather than discretion”; now there’s no better way to sum up Jenrick’s disgraceful governmental career to date than “discretion rather than rules”.

In the background, of course, are the unique fiscal and financial circumstances produced by Covid, in which all notions of prudence have been thrown out of the window. With the Bank of England buying most of the additional government bonds issued over the last 15 months (beyond the wildest imaginings of Balls and Brown), and with the cost of borrowing close to zero, the rationale for strict fiscal discipline or austerity has currently evaporated. Paradoxically, a situation in which the Treasury can find an emergency £60bn to pay the country’s wages makes for a popular chancellor, but may make for a less powerful Treasury.

Amid all this, Labour is left in an unenviable position, which is in many ways deeply unfair. So long as the Tories are associated with Brexit, England and Johnson, the voters don’t expect them to exercise any kind of discipline, fiscal or otherwise. Meanwhile, Labour remains associated with a Treasury worldview: technocratic, London-centric, British not English, rules not discretion. What’s doubly unfair is that, thanks to the serial fictions of Osborne and the Tory press from 2010 onwards that Labour had “spent all the money”, it is not even viewed as economically trustworthy. In the end, it turned out that public perceptions of financial credibility were largely shaped by political messaging and media narratives, not by adherence to self-imposed fiscal rules.

In the eyes of party members, New Labour will be for ever tarred by Blair and Iraq. In the eyes of much of the country, however, it will be tarred by some vague memory of centralised Brownite spending regimes. The fact that Labour receives so little credit for Brown’s undoubted successes as a spending chancellor is due to many factors, but ultimately consists in the fact that the technocratic, Treasury view of the world was never adequately translated into a political story. Osborne simply presented himself as the inheritor of a centralised “mess” that needed cleaning up.

The recent elections demonstrated that all political momentum is now with the cities and nations of Britain: the Conservatives in leave-voting England, Andy Burnham in Manchester, the SNP in Scotland, Labour in Wales. Rather than making weak gestures towards the union jack or against London, Labour needs to think deeply about the kind of statecraft and policy style that is suited to such a moment, so as to finally leave the world of Granita and “golden rules” behind.

The Conservative party’s growing electoral dominance in non-metropolitan England, so starkly re-emphasised by results in the north-east, has been attributed to various causes. Brexit and the popularity of Boris Johnson both count for a great deal. But while Labour is busy telling voters how much it deserved to lose, this is only half the picture. A major part of Johnson’s appeal is the way he has escaped the shadow cast by one of Britain’s three most significant political figures of the past 45 years: not Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair, but Gordon Brown.

The 1994 meeting between Blair and Brown at the Granita restaurant in Islington, north London, shortly after John Smith’s death, is the founding myth of New Labour: the moment when Brown agreed to let Blair stand for the leadership, on certain conditions. In addition to Blair’s much disputed commitment to serve only two terms in office should he become prime minister, there was also his promise that Brown, as chancellor, would get control over the domestic policy agenda. At least the second of these commitments was honoured, resulting in a situation where, from 1997 to 2007, the Treasury held an overwhelming dominance over the rest of Whitehall, while Brown was implicitly unsackable.

But, together with his adviser Ed Balls, Brown was also the architect of a new apparatus of economic policymaking designed for the era of globalisation. The central problem that Balls and Brown confronted was how to build the capacity for higher levels of social spending, while also retaining financial credibility in an age of far more mobile capital than any confronted by previous Labour governments. The fear was that, with financial capital able to cross borders at speed, a high-spending government might be viewed suspiciously by investors and lenders, making it harder for the state to borrow cheaply. The first part of their answer endures to this day: operational independence was handed to the Bank of England, accompanied by an inflation target. No longer could politicians seek to win elections by cutting interest rates, a move that aimed to win the trust of the markets.

On top of this, Brown also introduced a culture of almost obsessive fiscal discipline, as if the bond markets would attack the moment he showed any flexibility – the same paranoia that shaped Clintonism. His “golden rule”, outlined in his first budget, stated that, over the economic cycle, the government could borrow only to invest, not for day-to-day spending. The Treasury governed the rest of Whitehall according to a strict economic rubric, demanding every spending proposal was audited according to orthodox neoclassical economics.

Balls later wrote that their thinking had been guided by an influential 1977 article, Rules Rather than Discretion, in which two economists, Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott, sought to demonstrate that policymakers will produce far better economic outcomes if they stick rigidly to certain principles and heuristics of policy, rather than seeking to intervene on a case-by-case basis. Brown’s robotic persona and his mantra of “prudence” conveyed a programme that was so focused on policy as to be oblivious to more frivolous aspects of politics.

Elements of this Brownite machine remained in place during the David Cameron-George Osborne years: a chancellor acting as a kind of parallel prime minister, transforming society through force of cost-benefit analysis, only now the fiscal tide was going out rather than in. Even “Spreadsheet Phil” Hammond sustained the template as far as he could, in the face of ever-rising attacks from the Brexit extremists in his own party. The point is that, from 1997 to 2019, the government largely meant the Treasury. Those powers that are so foundational for the modern nation state – to tax, borrow and spend – were the basis on which governments asked to be judged, by voters and financial markets.

Various things have happened to weaken the Treasury’s political authority over the past five years, though – significantly – none of these has yet seemed to weaken the government’s credibility in the eyes of the markets. First, there was the notorious cooked Brexit forecast published in May 2016, predicting an immediate recession, half a million job losses and a house price crash, should Britain vote to leave. The referendum itself, a mass refusal to view the world in terms of macroeconomics, meant there could be no going back to a world in which politics was dominated by economists.

Consider how different things are now from in Brown’s heyday. Johnson’s first chancellor, Sajid Javid, lasted little more than six months in the job, resigning after one of his aides was sacked by Dominic Cummings without his knowledge. His second, Rishi Sunak, may have high political ambitions and approval ratings, but scarcely forms the kind of double-act with Johnson that Brown did with Blair, or Osborne with Cameron. Johnson’s cabinet is notable for lacking any obvious next-in-line leader.

What’s more interesting are the parts of Whitehall that have suddenly risen in profile under Johnson: communities and local government under Robert Jenrick, and the Department for Digital, Culture Media and Sport under Oliver Dowden. With the “levelling up” agenda of the former, (manifest in such pork barrel politics as the Towns Fund) and the “culture war” agenda of the latter (evident in attacks on the autonomy of museums), a new vision of government is emerging, one that is no longer afraid of expressing cultural favouritism or fixing deals. Balls and Brown were inspired by “rules rather than discretion”; now there’s no better way to sum up Jenrick’s disgraceful governmental career to date than “discretion rather than rules”.

In the background, of course, are the unique fiscal and financial circumstances produced by Covid, in which all notions of prudence have been thrown out of the window. With the Bank of England buying most of the additional government bonds issued over the last 15 months (beyond the wildest imaginings of Balls and Brown), and with the cost of borrowing close to zero, the rationale for strict fiscal discipline or austerity has currently evaporated. Paradoxically, a situation in which the Treasury can find an emergency £60bn to pay the country’s wages makes for a popular chancellor, but may make for a less powerful Treasury.

Amid all this, Labour is left in an unenviable position, which is in many ways deeply unfair. So long as the Tories are associated with Brexit, England and Johnson, the voters don’t expect them to exercise any kind of discipline, fiscal or otherwise. Meanwhile, Labour remains associated with a Treasury worldview: technocratic, London-centric, British not English, rules not discretion. What’s doubly unfair is that, thanks to the serial fictions of Osborne and the Tory press from 2010 onwards that Labour had “spent all the money”, it is not even viewed as economically trustworthy. In the end, it turned out that public perceptions of financial credibility were largely shaped by political messaging and media narratives, not by adherence to self-imposed fiscal rules.

In the eyes of party members, New Labour will be for ever tarred by Blair and Iraq. In the eyes of much of the country, however, it will be tarred by some vague memory of centralised Brownite spending regimes. The fact that Labour receives so little credit for Brown’s undoubted successes as a spending chancellor is due to many factors, but ultimately consists in the fact that the technocratic, Treasury view of the world was never adequately translated into a political story. Osborne simply presented himself as the inheritor of a centralised “mess” that needed cleaning up.

The recent elections demonstrated that all political momentum is now with the cities and nations of Britain: the Conservatives in leave-voting England, Andy Burnham in Manchester, the SNP in Scotland, Labour in Wales. Rather than making weak gestures towards the union jack or against London, Labour needs to think deeply about the kind of statecraft and policy style that is suited to such a moment, so as to finally leave the world of Granita and “golden rules” behind.

Tuesday, 18 May 2021

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)