'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 27 September 2023

Friday, 23 June 2023

Britain is the Dorian Gray economy, hiding its ugly truths from the world. Now they are exposed

You know the central conceit of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, of course you do. A lad of sun-kissed beauty is presented with a stunning likeness of himself. Disturbed at the notion that he will grow old while the painting doesn’t, he locks it away – where it is the portrait that ages and uglifies while Dorian stays boyish and beautiful. But perhaps you’ve forgotten what happens next.

The story has come to my mind many times, as the foulness of British politics becomes ever harder to ignore. Genteel liberals wonder how their land of cricket whites and orderly queues could be ruled by a grasping liar such as Boris Johnson and I hear a whisper on the wind: Dorian Gray. The New York Times and Der Spiegel report in bewilderment on a country with pockets of deep poverty and unslaked anger, and again rasps that hoarse voice: the horror was hidden here all along.

Now it’s all out in the open. In one of the richest societies in human history, inhabitants are starting to twig that by 2030 or thereabouts they will earn less per head than the Poles they so recently patronised. Whatever the politicians and pundits may argue, this debacle owes nothing to Jeremy Corbyn or Brexit or any supposedly un-British “populism”. It is homegrown and has deep roots.

Like Dorian Gray, Britain has for too long presented one face to the world while concealing the awful truth. The author of that novel, Oscar Wilde, was the son of an Irish nationalist and a graduate of Oxford, where he became a fine student of the British upper classes and their mellifluous hypocrisy. He would have recognised much of the mess we’re in, because it grew among shadows and cover-ups. From Tony Blair’s Cool Britannia through to George Osborne’s “march of the makers”, our rulers have trumpeted every false success, while ugly facts have been waved away as anomalies: from the former manufacturing suburbs and towns turned into giant warehouses of surplus people, to the fact that 15% of adults in England are on antidepressants. We’re winning the global race, claimed David Cameron, even as the population’s life expectancy fell far behind other rich countries. We shan’t stunt future generations with debt, he boasted, as our five-year-olds became the shortest in Europe.

Or take the housing bubble that politicians pretended was true prosperity – until this week, as the Bank of England hiked rates for the 13th time in a row and the prospect of it bursting began to terrify them. Yet the Westminster classes blew their hardest into that bubble. As soon as estate agents were out of lockdown, Rishi Sunak gave up £6bn of taxpayers’ money for a stamp duty holiday – an act as prudent as pouring petrol on a fire. Many of those he lured up the property ladder will be hardest hit by rising mortgage rates. Analysis done for me by UK Finance suggests that 465,000 house purchases during that tax break were financed with two- or three-year fixed rate mortgages – the very ones running out right now. In other words, nearly half a million households took the chancellor’s inducement; many will plunge into dangerous financial straits; some face losing their homes. They were mis-sold a dream by Sunak. Still, at least the Tories enjoyed a bounce in the polls.

“Sin is a thing that writes itself across a man’s face,” Dorian is told by his portraitist Basil Hallward. “If a wretched man has a vice, it shows itself in the lines of his mouth, the droop of his eyelids, the moulding of his hands even … But you, Dorian, with your pure, bright, innocent face and your marvellous untroubled youth – I can’t believe anything against you.” The picture of Dorian, which would have revealed the grotesque truth, is hidden away. So, too, has the UK avoided admitting its ills. Even now, in a country where patently so little works for people who rely on work for their income, commentators and frontbenchers still blame supposedly all-powerful interlopers: Boris, Nigel, Jeremy. And from Sunak to Starmer, all push growth and jobs as the remedy for what ails us.

Yet growth in this country is falling and not because of Ukraine or Covid or Brexit. Since the 1950s, the growth rate adjusted for inflation has been on a gentle but insistent downward slide. Our economy has become ever more stagnant and dependent on debt. It is fatuous to pretend this is going to turn around through magicking Britain into an AI free-for-all or a jolly green industrial giant. Employment? One in four employees are on low weekly wages – either because the pay is too low or the hours aren’t enough – while the average real wage has flatlined for many years.

Much of this analysis comes from a new book, When Nothing Works, written by a team of scholars. Although specialising in economics and accountancy, what they have produced is an essential text for understanding British government: the polarised politics of a highly unequal and increasingly stagnant society.

Take the issue at the top of today’s agenda: wages. Why can’t you and I take home more money? Because of a lack of productivity, politicians will say. Yet the researchers point to how labour has got a smaller and smaller share of economic output since the 1970s.

If the same share of GDP was paid out in wages today as in 1976, the average working-age household would have an extra £9,744 a year. We haven’t lost that 10 grand a year through laziness at work but because politicians from Thatcher onwards smashed up trade unions, undermined labour rights, and crowed over the result as a “flexible labour market”. What they really created was a low-wage workforce, in a low-growth country ruled by politicians with low ambitions for everyone bar themselves.

“The prayer of your pride has been answered,” Basil counsels Dorian, when he finally sees the portrait and its horrific truth. “The prayer of your repentance will be answered also.” When Nothing Works will inevitably be termed pessimistic, but it is no such thing. Realism comes from facing who we are and dropping the pretence that a growth miracle is just around the corner. Instead of trying to boost “the economy”, it is high time to boost our people: to ensure they have the basics they need to live a life free from indignity and free to flourish. This will come from redistribution rather than growth, from replacing extractive businesses with fair ones. Such ideas will not go down well in SW1, where both Tory and Labour are increasingly hostile to pluralism and brittle in their dogmatism. Self-knowledge is the hardest knowledge, as one of the book’s authors, Karel Williams, says. And self-delusion leads eventually to disaster.

Unable to face his loathsome self-image, Dorian slashes that portrait. He is found by servants. “Lying on the floor was a dead man, in evening dress, with a knife in his heart. He was withered, wrinkled and loathsome of visage. It was not till they examined the rings that they recognised who it was.”

Sunday, 29 August 2021

Saturday, 27 March 2021

Aagamee Manushya Party / Human Future Party

We the members believe:

- Human knowledge and understanding are limited. We believe in a sceptical examination of all philosophies, knowledge systems and their methods.

- Life on planet earth appears on a downward spiral and all attempts should be made to prevent the extinction of the human race and its environment.

- Achievement of political power is crucial to achieving our objectives and all methods are fair.

- Land, labour, money, risk… are fictitious concepts and we will aim to search for better fictions to prevent the extinction of the human race and its environment.

Anybody can become a member of the party by affirming to the above four values and paying the requisite joining fee and annual membership charges.

Application form to join Aagamee Manushya Party / Human Future Party

I:

residing at:

hereby affirm:

- Human knowledge and understanding are limited. We believe in a sceptical examination of all philosophies, knowledge systems and their methods.

- Life on planet earth appears on a downward spiral and all attempts should be made to prevent the extinction of the human race and its environment.

- Achievement of political power is crucial to achieving our objectives and all methods are fair.

- Land, labour, money, risk… are fictitious concepts and we will aim to search for better fictions to prevent the extinction of the human race and its environment.

I wish to join The Aagamee Manushya Party / Human Future Party and promise to work in a diligent manner to propagating its values and beliefs.

I enclose the amount towards membership and annual subscription charges.

Signature

Friday, 4 December 2020

Saturday, 6 June 2020

Scientific or Pseudo Knowledge? How Lancet's reputation was destroyed

The Lancet is one of the oldest and most respected medical journals in the world. Recently, they published an article on Covid patients receiving hydroxychloroquine with a dire conclusion: the drug increases heartbeat irregularities and decreases hospital survival rates. This result was treated as authoritative, and major drug trials were immediately halted – because why treat anyone with an unsafe drug?

Now, that Lancet study has been retracted, withdrawn from the literature entirely, at the request of three of its authors who “can no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources”. Given the seriousness of the topic and the consequences of the paper, this is one of the most consequential retractions in modern history.

---

It is natural to ask how this is possible. How did a paper of such consequence get discarded like a used tissue by some of its authors only days after publication? If the authors don’t trust it now, how did it get published in the first place?

The answer is quite simple. It happened because peer review, the formal process of reviewing scientific work before it is accepted for publication, is not designed to detect anomalous data. It makes no difference if the anomalies are due to inaccuracies, miscalculations, or outright fraud. This is not what peer review is for. While it is the internationally recognised badge of “settled science”, its value is far more complicated.

At its best, peer review is a slow and careful evaluation of new research by appropriate experts. It involves multiple rounds of revision that removes errors, strengthens analyses, and noticeably improves manuscripts.

At its worst, it is merely window dressing that gives the unwarranted appearance of authority, a cursory process which confers no real value, enforces orthodoxy, and overlooks both obvious analytical problems and outright fraud entirely.

Regardless of how any individual paper is reviewed – and the experience is usually somewhere between the above extremes – the sad truth is peer review in its entirety is struggling, and retractions like this drag its flaws into an incredibly bright spotlight.

The ballistics of this problem are well known. To start with, peer review is entirely unrewarded. The internal currency of science consists entirely of producing new papers, which form the cornerstone of your scientific reputation. There is no emphasis on reviewing the work of others. If you spend several days in a continuous back-and-forth technical exchange with authors, trying to improve their manuscript, adding new analyses, shoring up conclusions, no one will ever know your name. Neither are you paid. Peer review originally fitted under an amorphous idea of academic “service” – the tasks that scientists were supposed to perform as members of their community. This is a nice idea, but is almost invariably maintained by researchers with excellent job security. Some senior scientists are notorious for peer reviewing manuscripts rarely or even never – because it interferes with the task of producing more of their own research.

However, even if reliable volunteers for peer review can be found, it is increasingly clear that it is insufficient. The vast majority of peer-reviewed articles are never checked for any form of analytical consistency, nor can they be – journals do not require manuscripts to have accompanying data or analytical code and often will not help you obtain them from authors if you wish to see them. Authors usually have zero formal, moral, or legal requirements to share the data and analytical methods behind their experiments. Finally, if you locate a problem in a published paper and bring it to either of these parties, often the median response is no response at all – silence.

This is usually not because authors or editors are negligent or uncaring. Usually, it is because they are trying to keep up with the component difficulties of keeping their scientific careers and journals respectively afloat. Unfortunately, those goals are directly in opposition – authors publishing as much as possible means back-breaking amounts of submissions for journals. Increasingly time-poor researchers, busy with their own publications, often decline invitations to review. Subsequently, peer review is then cursory or non-analytical.

And even still, we often muddle through. Until we encounter extraordinary circumstances.

Peer review during a pandemic faces a brutal dilemma – the moral importance of releasing important information with planetary consequences quickly, versus the scientific importance of evaluating the presented work fully – while trying to recruit scientists, already busier than usual due to their disrupted lives, to review work for free. And, after this process is complete, publications face immediate scrutiny by a much larger group of engaged scientific readers than usual, who treat publications which affect the health of every living human being with the scrutiny they deserve.

The consequences are extreme. The consequences for any of us, on discovering a persistent cough and respiratory difficulties, are directly determined by this research. Papers like today’s retraction determine how people live or die tomorrow. They affect what drugs are recommended, what treatments are available, and how we get them sooner.

The immediate solution to this problem of extreme opacity, which allows flawed papers to hide in plain sight, has been advocated for years: require more transparency, mandate more scrutiny. Prioritise publishing papers which present data and analytical code alongside a manuscript. Re-analyse papers for their accuracy before publication, instead of just assessing their potential importance. Engage expert statistical reviewers where necessary, pay them if you must. Be immediately responsive to criticism, and enforce this same standard on authors. The alternative is more retractions, more missteps, more wasted time, more loss of public trust … and more death.

Sunday, 30 June 2019

The science of influencing people: six ways to win an argument

“I am quite sure now that often, very often, in matters of religion and politics a man’s reasoning powers are not above the monkey’s,” wrote Mark Twain.

Having written a book about our most common reasoning errors, I would argue that Twain was being rather uncharitable – to monkeys. Whether we are discussing Trump, Brexit, or the Tory leadership, we have all come across people who appear to have next to no understanding of world events – but who talk with the utmost confidence and conviction. And the latest psychological research can now help us to understand why.

Consider the “illusion of explanatory depth”. When asked about government policies and their consequences, most people believe that they could explain their workings in great detail. If put to the test, however, their explanations are vague and incoherent. The problem is that we confuse a shallow familiarity with general concepts for real, in-depth knowledge.

Besides being less substantial than we think, our knowledge is also highly selective: we conveniently remember facts that support our beliefs and forget others. When it comes to understanding the EU, for instance, Brexiters will know the overall costs of membership, while remainers will cite its numerous advantages. Although the overall level of knowledge is equal on both sides, there is little overlap in the details.

Simply asking why people support or oppose a policy is pointless. You need to ask how something works to have an effect

Politics can also scramble our critical thinking skills. Psychological studies show that people fail to notice the logical fallacies in an argument if the conclusion supports their viewpoint; if they are shown contrary evidence, however, they will be far more critical of the tiniest hole in the argument. This phenomenon is known as “motivated reasoning”.

A high standard of education doesn’t necessarily protect us from these flaws. Graduates, for instance, often overestimate their understanding of their degree subject: although they remember the general content, they have forgotten the details. “People confuse their current level of understanding with their peak knowledge,” Prof Matthew Fisher of Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, says. That false sense of expertise can, in turn, lead them to feel that they have the licence to be more closed-minded in their political views – an attitude known as “earned dogmatism”.

Little wonder that discussions about politics can leave us feeling that we are banging our heads against a brick wall – even when talking to people we might otherwise respect. Fortunately, recent psychological research also offers evidence-based ways towards achieving more fruitful discussions.

Ask ‘how’ rather than ‘why’

Thanks to the illusion of explanatory depth, many political arguments will be based on false premises, spoken with great confidence but with a minimal understanding of the issues at hand. For this reason, a simple but powerful way of deflating someone’s argument is to ask for more detail. “You need to get the ‘other side’ focusing on how something would play itself out, in a step by step fashion”, says Prof Dan Johnson at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. By revealing the shallowness of their existing knowledge, this prompts a more moderate and humble attitude.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Anti-Brexit protester Steve Bray and a pro-Brexit protester face off outside parliament earlier this year. Photograph: Jack Taylor/Getty Images

In 2013, Prof Philip Fernbach at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and colleagues asked participants in cap-and-trade schemes – designed to limit companies’ carbon emissions – to describe in depth how they worked. Subjects initially took strongly polarised views but after the limits of their knowledge were exposed, their attitudes became more moderate and less biased.

It’s important to note that simply asking why people supported or opposed the policy – without requiring them to explain how it works – had no effect, since those reasons could be shallower (“It helps the environment”) with little detail. You need to ask how something works to get the effect.

If you are debating the merits of a no-deal Brexit, you might ask someone to describe exactly how the UK’s international trade would change under WTO terms. If you are challenging a climate emergency denier, you might ask them to describe exactly how their alternative theories can explain the recent rise in temperatures. It’s a strategy that the broadcaster James O’Brien employs on his LBC talk show – to powerful effect.

Fill their knowledge gap with a convincing story

If you are trying to debunk a particular falsehood – like a conspiracy theory or fake news – you should make sure that your explanation offers a convincing, coherent narrative that fills all the gaps left in the other person’s understanding.

Consider the following experiment by Prof Brendan Nyhan of the University of Michigan and Prof Jason Reifler of the University of Exeter. Subjects read stories about a fictional senator allegedly under investigation for bribery who had subsequently resigned from his post. Written evidence – a letter from prosecutors confirming his innocence – did little to change the participants’ suspicions of his guilt. But when offered an alternative explanation for his resignation – to take on another role – participants changed their minds. The same can be seen in murder trials: people are more likely to accept someone’s innocence if another suspect has also been accused, since that fills the biggest gap in the story: whodunnit.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Boris Johnson, Jeremy Hunt, Michael Gove, Sajid Javid and Rory Stewart taking part in a BBC TV debate earlier this month. Photograph: Jeff Overs/BBC/PA

The persuasive power of well-constructed narratives means that it’s often useful to discuss the sources of misinformation, so that the person can understand why they were being misled in the first place. Anti-vaxxers, for instance, may believe a medical conspiracy to cover up the supposed dangers of vaccines. You are more likely to change minds if you replace that narrative with an equally cohesive and convincing story – such as Andrew Wakefield’s scientific fraud, and the fact that he was set to profit from his paper linking autism to MMR vaccines. Just stating the scientific evidence will not be as persuasive.

Reframe the issue

Each of our beliefs is deeply rooted in a much broader and more complex political ideology. Climate crisis denial, for instance, is now inextricably linked to beliefs in free trade, capitalism and the dangers of environmental regulation.

Attacking one issue may therefore threaten to unravel someone’s whole worldview – a feeling that triggers emotionally charged motivated reasoning. It is for this reason that highly educated Republicans in the US deny the overwhelming evidence.

You are not going to alter someone’s whole political ideology in one discussion, so a better strategy is to disentangle the issue at hand from their broader beliefs, or to explain how the facts can still be accommodated into their worldview. A free-market capitalist who denies global warming might be far more receptive to the evidence if you explain that the development of renewable energies could lead to technological breakthroughs and generate economic growth.

Appeal to an alternative identity

If the attempt to reframe the issue fails, you might have more success by appealing to another part of the person’s identity entirely.

Someone’s political affiliation will never completely define them, after all. Besides being a conservative or a socialist, a Brexiter or a remainer, we associate ourselves with other traits and values – things like our profession, or our role as a parent. We might see ourselves as a particularly honest person, or someone who is especially creative. “All people have multiple identities,” says Prof Jay Van Bavel at New York University, who studies the neuroscience of the “partisan brain”. “These identities can become active at any given time, depending on the circumstances.”

You are more likely to achieve your aims by arguing gently and kindly. You will also come across better to onlookers

It’s natural that when talking about politics, the salient identity will be our support for a particular party or movement. But when people are asked to first reflect on their other, nonpolitical values, they tend to become more objective in discussion on highly partisan issues, as they stop viewing facts through their ideological lens.

You could try to use this to your advantage during a heated conversation, with subtle flattery that appeals to another identity and its set of values; if you are talking to a science teacher, you might try to emphasise their capacity to appraise evidence even-handedly. The aim is to help them recognise that they can change their mind on certain issues while staying true to other important elements of their personality.

Persuade them to take an outside perspective

Another simple strategy to encourage a more detached and rational mindset is to ask your conversation partner to imagine the argument from the viewpoint of someone from another country. How, for example, would someone in Australia or Iceland view Boris Johnson as our new prime minister?

Prof Ethan Kross at the University of Michigan, and Prof Igor Grossmann at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada, have shown that this strategy increases “psychological distance” from the issue at hand and cools emotionally charged reasoning so that you can see things more objectively. During the US presidential elections, for instance, their participants were asked to consider how someone in Iceland would view the candidates. They were subsequently more willing to accept the limits of their knowledge and to listen to alternative viewpoints; after the experiment, they were even more likely to join a bipartisan discussion group.

FacebookTwitterPinterest The front pages of two New York newspapers on Friday 2 June 2017, as Donald Trump pledged to withdraw the US from the Paris climate agreement. Photograph: Richard B Levine/Alamy

This is only one way to increase someone’s psychological distance, and there are many others. If you are considering policies with potentially long-term consequences, you could ask them to imagine viewing the situation through the eyes of someone in the future. However you do it, encouraging this shift in perspective should make your friend or relative more receptive to the facts you are presenting, rather than simply reacting with knee-jerk dismissals.

Be kind

Here’s a lesson that certain polemicists in the media might do well to remember – people are generally much more rational in their arguments, and more willing to own up to the limits of their knowledge and understanding, if they are treated with respect and compassion. Aggression, by contrast, leads them to feel that their identity is threatened, which in turn can make them closed-minded.

Assuming that the purpose of your argument is to change minds, rather than to signal your own superiority, you are much more likely to achieve your aims by arguing gently and kindly rather than belligerently, and affirming your respect for the person, even if you are telling them some hard truths. As a bonus, you will also come across better to onlookers. “There’s a lot of work showing that third-party observers always attribute high levels of competence when the person is conducting themselves with more civility,” says Dr Joe Vitriol, a psychologist at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. As Lady Mary Wortley Montagu put it in the 18th century: “Civility costs nothing and buys everything.”

Wednesday, 16 January 2019

Saturday, 15 September 2018

What I learnt from being fired

The anniversary of Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy has prompted lots of reflection on the damage done. But there were winners, too. I was one of them: I got fired. A decade ago I was an analyst at a hedge fund. We owned some stocks, and bet against others. At the end of 2008, after five years at the fund and with Wall Street flat on its back, I was let go.

Getting sacked is not the standard way to win in a market collapse. Some will argue that, say, John Paulson, who made $4bn personally betting against mortgages, comes away looking better than I do. This strikes me as a rather conventional take. In any case, the crisis taught me two key things and, more importantly, saved me a lot of embarrassment.

The first thing I learnt is that doing the right thing only goes so far. The two portfolio managers at my fund were smart and despised risk, and they were quick to recognise that something serious was going on. As they only owned stuff that was easy to sell, sell they did, and early on. Their clients lost nothing during the crisis and the fund survived. But the clients pulled their money anyway. They needed it and we, not having lost it, had it. So expenses had to be cut, and I was one of them.

The economy — or, if you prefer, the universe — is a big machine. No matter how smart or careful you are, you might get caught in the gears. Most people learn this eventually. I’m just glad I learnt it by losing a job rather than by, for example, getting struck dead by a meteor.

Lesson two. In a crisis, nobody knows anything. The writer William Goldman made this point about Hollywood: until you get a movie in front of the audience, no one can say with anything like certainty whether it is good or not. Most of the time, by contrast, finance is a business where the important variables are predictable to within a certain range. But when a storm comes, finance is — no matter what anybody tells you in retrospect — as mysterious and fickle as a popcorn-gobbling rabble. Because that is what, in the final analysis, it is.

At one point in 2007 I was working with two colleagues on a simple job: determine which of the big European banks have significant exposure to US housing. But the banks were, for some reason, hesitant to answer our questions in very clear terms. In some cases they seemed oddly unwilling to answer the phone.

Nor did the thousands of pages of disclosures from the banks contain anything helpful. The annual reports that had previously appeared to me to be precise quantitative descriptions of businesses looked, suddenly, like a brittle superstructure of certainty erected over a heaving morass of unknowns.

It is reassuring to think of this like a freshman-philosophy Socrates. Knowing what you don’t know is the beginning of wisdom, and all that. That is a comforting thought when you are sitting in a lecture hall on a crisp autumn afternoon. When you are lost in the woods, knowing what you don’t know is just scary as hell.

I should note that internalising these two points — that I am not in control, and don’t know much — has cost me money. It has made me much too conservative in how I have my savings invested, and I’ve missed much of the current stock market rally. At the same time, though, I think it has made me a better person and a clearer writer. It is a trade-off I can accept.

That the effect of the crisis was to make me reflective and over-cautious reveals something else. I probably did not belong in finance in the first place. The low prices of stocks after the crisis made good investors greedy. They made me contemplate the vanity of all human striving.

That is how the crisis shielded me from embarrassment. As it was, I lost my job when a lot of other people did. No one was surprised then and no one asks for an explanation now. It was just one of those things that happens. If there had been no crisis, my guess is that somebody would have got around to firing me for being useless. Which would have been awkward.

Finance, like law, is a profession that attracts a lot of reasonably intelligent, hard-working people who rather like money. People like me. Most of us are not really suited to it, though, and that makes for a lot of unhappy careers. The financial crisis saved me from that, and I am grateful.

Sunday, 20 May 2018

Why the 'Right to Believe' Is Not a Right to Believe Whatever You Want

Do we have the right to believe whatever we want to believe? This supposed right is often claimed as the last resort of the wilfully ignorant, the person who is cornered by evidence and mounting opinion: ‘I believe climate change is a hoax whatever anyone else says, and I have a right to believe it!’ But is there such a right?

We do recognise the right to know certain things. I have a right to know the conditions of my employment, the physician’s diagnosis of my ailments, the grades I achieved at school, the name of my accuser and the nature of the charges, and so on. But belief is not knowledge.

Beliefs are factive: to believe is to take to be true. It would be absurd, as the analytic philosopher G.E. Moore observed in the 1940s, to say: ‘It is raining, but I don’t believe that it is raining.’ Beliefs aspire to truth – but they do not entail it. Beliefs can be false, unwarranted by evidence or reasoned consideration. They can also be morally repugnant. Among likely candidates: beliefs that are sexist, racist or homophobic; the belief that proper upbringing of a child requires ‘breaking the will’ and severe corporal punishment; the belief that the elderly should routinely be euthanised; the belief that ‘ethnic cleansing’ is a political solution, and so on. If we find these morally wrong, we condemn not only the potential acts that spring from such beliefs, but the content of the belief itself, the act of believing it, and thus the believer.

Such judgments can imply that believing is a voluntary act. But beliefs are often more like states of mind or attitudes than decisive actions. Some beliefs, such as personal values, are not deliberately chosen; they are ‘inherited’ from parents and ‘acquired’ from peers, acquired inadvertently, inculcated by institutions and authorities, or assumed from hearsay. For this reason, I think, it is not always the coming-to-hold-this-belief that is problematic; it is rather the sustaining of such beliefs, the refusal to disbelieve or discard them that can be voluntary and ethically wrong.

If the content of a belief is judged morally wrong, it is also thought to be false. The belief that one race is less than fully human is not only a morally repugnant, racist tenet; it is also thought to be a false claim – though not by the believer. The falsity of a belief is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a belief to be morally wrong; neither is the ugliness of the content sufficient for a belief to be morally wrong. Alas, there are indeed morally repugnant truths, but it is not the believing that makes them so. Their moral ugliness is embedded in the world, not in one’s belief about the world.

‘Who are you to tell me what to believe?’ replies the zealot. It is a misguided challenge: it implies that certifying one’s beliefs is a matter of someone’s authority. It ignores the role of reality. Believing has what philosophers call a ‘mind-to-world direction of fit’. Our beliefs are intended to reflect the real world – and it is on this point that beliefs can go haywire. There are irresponsible beliefs; more precisely, there are beliefs that are acquired and retained in an irresponsible way. One might disregard evidence; accept gossip, rumour, or testimony from dubious sources; ignore incoherence with one’s other beliefs; embrace wishful thinking; or display a predilection for conspiracy theories.

I do not mean to revert to the stern evidentialism of the 19th-century mathematical philosopher William K Clifford, who claimed: ‘It is wrong, always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.’ Clifford was trying to prevent irresponsible ‘overbelief’, in which wishful thinking, blind faith or sentiment (rather than evidence) stimulate or justify belief. This is too restrictive. In any complex society, one has to rely on the testimony of reliable sources, expert judgment and the best available evidence. Moreover, as the psychologist William James responded in 1896, some of our most important beliefs about the world and the human prospect must be formed without the possibility of sufficient evidence. In such circumstances (which are sometimes defined narrowly, sometimes more broadly in James’s writings), one’s ‘will to believe’ entitles us to choose to believe the alternative that projects a better life.

In exploring the varieties of religious experience, James would remind us that the ‘right to believe’ can establish a climate of religious tolerance. Those religions that define themselves by required beliefs (creeds) have engaged in repression, torture and countless wars against non-believers that can cease only with recognition of a mutual ‘right to believe’. Yet, even in this context, extremely intolerant beliefs cannot be tolerated. Rights have limits and carry responsibilities.

Unfortunately, many people today seem to take great licence with the right to believe, flouting their responsibility. The wilful ignorance and false knowledge that are commonly defended by the assertion ‘I have a right to my belief’ do not meet James’s requirements. Consider those who believe that the lunar landings or the Sandy Hook school shooting were unreal, government-created dramas; that Barack Obama is Muslim; that the Earth is flat; or that climate change is a hoax. In such cases, the right to believe is proclaimed as a negative right; that is, its intent is to foreclose dialogue, to deflect all challenges; to enjoin others from interfering with one’s belief-commitment. The mind is closed, not open for learning. They might be ‘true believers’, but they are not believers in the truth.

Believing, like willing, seems fundamental to autonomy, the ultimate ground of one’s freedom. But, as Clifford also remarked: ‘No one man’s belief is in any case a private matter which concerns himself alone.’ Beliefs shape attitudes and motives, guide choices and actions. Believing and knowing are formed within an epistemic community, which also bears their effects. There is an ethic of believing, of acquiring, sustaining, and relinquishing beliefs – and that ethic both generates and limits our right to believe. If some beliefs are false, or morally repugnant, or irresponsible, some beliefs are also dangerous. And to those, we have no right.

Thursday, 22 December 2016

Learn Anything In Four Steps - The Feynman Technique

Sunday, 4 December 2016

Are women evil? - Google, democracy and the truth about internet search

Here’s what you don’t want to do late on a Sunday night. You do not want to type seven letters into Google. That’s all I did. I typed: “a-r-e”. And then “j-e-w-s”. Since 2008, Google has attempted to predict what question you might be asking and offers you a choice. And this is what it did. It offered me a choice of potential questions it thought I might want to ask: “are jews a race?”, “are jews white?”, “are jews christians?”, and finally, “are jews evil?”

Are Jews evil? It’s not a question I’ve ever thought of asking. I hadn’t gone looking for it. But there it was. I press enter. A page of results appears. This was Google’s question. And this was Google’s answer: Jews are evil. Because there, on my screen, was the proof: an entire page of results, nine out of 10 of which “confirm” this. The top result, from a site called Listovative, has the headline: “Top 10 Major Reasons Why People Hate Jews.” I click on it: “Jews today have taken over marketing, militia, medicinal, technological, media, industrial, cinema challenges etc and continue to face the worlds [sic] envy through unexplained success stories given their inglorious past and vermin like repression all over Europe.”

Google is search. It’s the verb, to Google. It’s what we all do, all the time, whenever we want to know anything. We Google it. The site handles at least 63,000 searches a second, 5.5bn a day. Its mission as a company, the one-line overview that has informed the company since its foundation and is still the banner headline on its corporate website today, is to “organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. It strives to give you the best, most relevant results. And in this instance the third-best, most relevant result to the search query “are Jews… ” is a link to an article from stormfront.org, a neo-Nazi website. The fifth is a YouTube video: “Why the Jews are Evil. Why we are against them.”

The sixth is from Yahoo Answers: “Why are Jews so evil?” The seventh result is: “Jews are demonic souls from a different world.” And the 10th is from jesus-is-saviour.com: “Judaism is Satanic!”

There’s one result in the 10 that offers a different point of view. It’s a link to a rather dense, scholarly book review from thetabletmag.com, a Jewish magazine, with the unfortunately misleading headline: “Why Literally Everybody In the World Hates Jews.”

I feel like I’ve fallen down a wormhole, entered some parallel universe where black is white, and good is bad. Though later, I think that perhaps what I’ve actually done is scraped the topsoil off the surface of 2016 and found one of the underground springs that has been quietly nurturing it. It’s been there all the time, of course. Just a few keystrokes away… on our laptops, our tablets, our phones. This isn’t a secret Nazi cell lurking in the shadows. It’s hiding in plain sight.

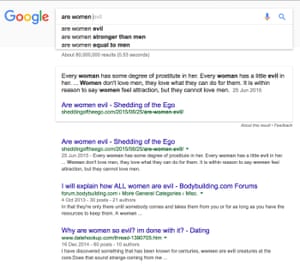

Are women… Google’s search results.

Stories about fake news on Facebook have dominated certain sections of the press for weeks following the American presidential election, but arguably this is even more powerful, more insidious. Frank Pasquale, professor of law at the University of Maryland, and one of the leading academic figures calling for tech companies to be more open and transparent, calls the results “very profound, very troubling”.

He came across a similar instance in 2006 when, “If you typed ‘Jew’ in Google, the first result was jewwatch.org. It was ‘look out for these awful Jews who are ruining your life’. And the Anti-Defamation League went after them and so they put an asterisk next to it which said: ‘These search results may be disturbing but this is an automated process.’ But what you’re showing – and I’m very glad you are documenting it and screenshotting it – is that despite the fact they have vastly researched this problem, it has gotten vastly worse.”

And ordering of search results does influence people, says Martin Moore, director of the Centre for the Study of Media, Communication and Power at King’s College, London, who has written at length on the impact of the big tech companies on our civic and political spheres. “There’s large-scale, statistically significant research into the impact of search results on political views. And the way in which you see the results and the types of results you see on the page necessarily has an impact on your perspective.” Fake news, he says, has simply “revealed a much bigger problem. These companies are so powerful and so committed to disruption. They thought they were disrupting politics but in a positive way. They hadn’t thought about the downsides. These tools offer remarkable empowerment, but there’s a dark side to it. It enables people to do very cynical, damaging things.”

Google is knowledge. It’s where you go to find things out. And evil Jews are just the start of it. There are also evil women. I didn’t go looking for them either. This is what I type: “a-r-e w-o-m-e-n”. And Google offers me just two choices, the first of which is: “Are women evil?” I press return. Yes, they are. Every one of the 10 results “confirms” that they are, including the top one, from a site called sheddingoftheego.com, which is boxed out and highlighted: “Every woman has some degree of prostitute in her. Every woman has a little evil in her… Women don’t love men, they love what they can do for them. It is within reason to say women feel attraction but they cannot love men.”

Next I type: “a-r-e m-u-s-l-i-m-s”. And Google suggests I should ask: “Are Muslims bad?” And here’s what I find out: yes, they are. That’s what the top result says and six of the others. Without typing anything else, simply putting the cursor in the search box, Google offers me two new searches and I go for the first, “Islam is bad for society”. In the next list of suggestions, I’m offered: “Islam must be destroyed.”

Jews are evil. Muslims need to be eradicated. And Hitler? Do you want to know about Hitler? Let’s Google it. “Was Hitler bad?” I type. And here’s Google’s top result: “10 Reasons Why Hitler Was One Of The Good Guys” I click on the link: “He never wanted to kill any Jews”; “he cared about conditions for Jews in the work camps”; “he implemented social and cultural reform.” Eight out of the other 10 search results agree: Hitler really wasn’t that bad.

A few days later, I talk to Danny Sullivan, the founding editor of SearchEngineLand.com. He’s been recommended to me by several academics as one of the most knowledgeable experts on search. Am I just being naive, I ask him? Should I have known this was out there? “No, you’re not being naive,” he says. “This is awful. It’s horrible. It’s the equivalent of going into a library and asking a librarian about Judaism and being handed 10 books of hate. Google is doing a horrible, horrible job of delivering answers here. It can and should do better.”

He’s surprised too. “I thought they stopped offering autocomplete suggestions for religions in 2011.” And then he types “are women” into his own computer. “Good lord! That answer at the top. It’s a featured result. It’s called a “direct answer”. This is supposed to be indisputable. It’s Google’s highest endorsement.” That every women has some degree of prostitute in her? “Yes. This is Google’s algorithm going terribly wrong.”

I contacted Google about its seemingly malfunctioning autocomplete suggestions and received the following response: “Our search results are a reflection of the content across the web. This means that sometimes unpleasant portrayals of sensitive subject matter online can affect what search results appear for a given query. These results don’t reflect Google’s own opinions or beliefs – as a company, we strongly value a diversity of perspectives, ideas and cultures.”

Google isn’t just a search engine, of course. Search was the foundation of the company but that was just the beginning. Alphabet, Google’s parent company, now has the greatest concentration of artificial intelligence experts in the world. It is expanding into healthcare, transportation, energy. It’s able to attract the world’s top computer scientists, physicists and engineers. It’s bought hundreds of start-ups, including Calico, whose stated mission is to “cure death” and DeepMind, which aims to “solve intelligence”.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin in 2002. Photograph: Michael Grecco/Getty Images

And 20 years ago it didn’t even exist. When Tony Blair became prime minister, it wasn’t possible to Google him: the search engine had yet to be invented. The company was only founded in 1998 and Facebook didn’t appear until 2004. Google’s founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page are still only 43. Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook is 32. Everything they’ve done, the world they’ve remade, has been done in the blink of an eye.

But it seems the implications about the power and reach of these companies is only now seeping into the public consciousness. I ask Rebecca MacKinnon, director of the Ranking Digital Rights project at the New America Foundation, whether it was the recent furore over fake news that woke people up to the danger of ceding our rights as citizens to corporations. “It’s kind of weird right now,” she says, “because people are finally saying, ‘Gee, Facebook and Google really have a lot of power’ like it’s this big revelation. And it’s like, ‘D’oh.’”

MacKinnon has a particular expertise in how authoritarian governments adapt to the internet and bend it to their purposes. “China and Russia are a cautionary tale for us. I think what happens is that it goes back and forth. So during the Arab spring, it seemed like the good guys were further ahead. And now it seems like the bad guys are. Pro-democracy activists are using the internet more than ever but at the same time, the adversary has gotten so much more skilled.”

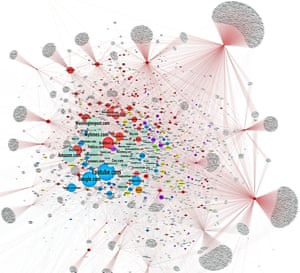

Last week Jonathan Albright, an assistant professor of communications at Elon University in North Carolina, published the first detailed research on how rightwing websites had spread their message. “I took a list of these fake news sites that was circulating, I had an initial list of 306 of them and I used a tool – like the one Google uses – to scrape them for links and then I mapped them. So I looked at where the links went – into YouTube and Facebook, and between each other, millions of them… and I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing.

“They have created a web that is bleeding through on to our web. This isn’t a conspiracy. There isn’t one person who’s created this. It’s a vast system of hundreds of different sites that are using all the same tricks that all websites use. They’re sending out thousands of links to other sites and together this has created a vast satellite system of rightwing news and propaganda that has completely surrounded the mainstream media system.

He found 23,000 pages and 1.3m hyperlinks. “And Facebook is just the amplification device. When you look at it in 3D, it actually looks like a virus. And Facebook was just one of the hosts for the virus that helps it spread faster. You can see the New York Times in there and the Washington Post and then you can see how there’s a vast, vast network surrounding them. The best way of describing it is as an ecosystem. This really goes way beyond individual sites or individual stories. What this map shows is the distribution network and you can see that it’s surrounding and actually choking the mainstream news ecosystem.”

Like a cancer? “Like an organism that is growing and getting stronger all the time.”

Charlie Beckett, a professor in the school of media and communications at LSE, tells me: “We’ve been arguing for some time now that plurality of news media is good. Diversity is good. Critiquing the mainstream media is good. But now… it’s gone wildly out of control. What Jonathan Albright’s research has shown is that this isn’t a byproduct of the internet. And it’s not even being done for commercial reasons. It’s motivated by ideology, by people who are quite deliberately trying to destabilise the internet.”

A spatial map of the rightwing fake news ecosystem. Jonathan Albright, assistant professor of communications at Elon University, North Carolina, “scraped” 300 fake news sites (the dark shapes on this map) to reveal the 1.3m hyperlinks that connect them together and link them into the mainstream news ecosystem. Here, Albright shows it is a “vast satellite system of rightwing news and propaganda that has completely surrounded the mainstream media system”. Photograph: Jonathan Albright

Albright’s map also provides a clue to understanding the Google search results I found. What these rightwing news sites have done, he explains, is what most commercial websites try to do. They try to find the tricks that will move them up Google’s PageRank system. They try and “game” the algorithm. And what his map shows is how well they’re doing that.

That’s what my searches are showing too. That the right has colonised the digital space around these subjects – Muslims, women, Jews, the Holocaust, black people – far more effectively than the liberal left.

“It’s an information war,” says Albright. “That’s what I keep coming back to.”

But it’s where it goes from here that’s truly frightening. I ask him how it can be stopped. “I don’t know. I’m not sure it can be. It’s a network. It’s far more powerful than any one actor.”

So, it’s almost got a life of its own? “Yes, and it’s learning. Every day, it’s getting stronger.”

The more people who search for information about Jews, the more people will see links to hate sites, and the more they click on those links (very few people click on to the second page of results) the more traffic the sites will get, the more links they will accrue and the more authoritative they will appear. This is an entirely circular knowledge economy that has only one outcome: an amplification of the message. Jews are evil. Women are evil. Islam must be destroyed. Hitler was one of the good guys.

And the constellation of websites that Albright found – a sort of shadow internet – has another function. More than just spreading rightwing ideology, they are being used to track and monitor and influence anyone who comes across their content. “I scraped the trackers on these sites and I was absolutely dumbfounded. Every time someone likes one of these posts on Facebook or visits one of these websites, the scripts are then following you around the web. And this enables data-mining and influencing companies like Cambridge Analytica to precisely target individuals, to follow them around the web, and to send them highly personalised political messages. This is a propaganda machine. It’s targeting people individually to recruit them to an idea. It’s a level of social engineering that I’ve never seen before. They’re capturing people and then keeping them on an emotional leash and never letting them go.”

Cambridge Analytica, an American-owned company based in London, was employed by both the Vote Leave campaign and the Trump campaign. Dominic Cummings, the campaign director of Vote Leave, has made few public announcements since the Brexit referendum but he did say this: “If you want to make big improvements in communication, my advice is – hire physicists.”

Steve Bannon, founder of Breitbart News and the newly appointed chief strategist to Trump, is on Cambridge Analytica’s board and it has emerged that the company is in talks to undertake political messaging work for the Trump administration. It claims to have built psychological profiles using 5,000 separate pieces of data on 220 million American voters. It knows their quirks and nuances and daily habits and can target them individually.

“They were using 40-50,000 different variants of ad every day that were continuously measuring responses and then adapting and evolving based on that response,” says Martin Moore of Kings College. Because they have so much data on individuals and they use such phenomenally powerful distribution networks, they allow campaigns to bypass a lot of existing laws.

“It’s all done completely opaquely and they can spend as much money as they like on particular locations because you can focus on a five-mile radius or even a single demographic. Fake news is important but it’s only one part of it. These companies have found a way of transgressing 150 years of legislation that we’ve developed to make elections fair and open.”

Did such micro-targeted propaganda – currently legal – swing the Brexit vote? We have no way of knowing. Did the same methods used by Cambridge Analytica help Trump to victory? Again, we have no way of knowing. This is all happening in complete darkness. We have no way of knowing how our personal data is being mined and used to influence us. We don’t realise that the Facebook page we are looking at, the Google page, the ads that we are seeing, the search results we are using, are all being personalised to us. We don’t see it because we have nothing to compare it to. And it is not being monitored or recorded. It is not being regulated. We are inside a machine and we simply have no way of seeing the controls. Most of the time, we don’t even realise that there are controls.

Facebook and Google move to kick fake news sites off their ad networks

Rebecca MacKinnon says that most of us consider the internet to be like “the air that we breathe and the water that we drink”. It surrounds us. We use it. And we don’t question it. “But this is not a natural landscape. Programmers and executives and editors and designers, they make this landscape. They are human beings and they all make choices.”

But we don’t know what choices they are making. Neither Google or Facebook make their algorithms public. Why did my Google search return nine out of 10 search results that claim Jews are evil? We don’t know and we have no way of knowing. Their systems are what Frank Pasquale describes as “black boxes”. He calls Google and Facebook “a terrifying duopoly of power” and has been leading a growing movement of academics who are calling for “algorithmic accountability”. “We need to have regular audits of these systems,” he says. “We need people in these companies to be accountable. In the US, under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, every company has to have a spokesman you can reach. And this is what needs to happen. They need to respond to complaints about hate speech, about bias.”

Is bias built into the system? Does it affect the kind of results that I was seeing? “There’s all sorts of bias about what counts as a legitimate source of information and how that’s weighted. There’s enormous commercial bias. And when you look at the personnel, they are young, white and perhaps Asian, but not black or Hispanic and they are overwhelmingly men. The worldview of young wealthy white men informs all these judgments.”

Later, I speak to Robert Epstein, a research psychologist at the American Institute for Behavioural Research and Technology, and the author of the study that Martin Moore told me about (and that Google has publicly criticised), showing how search-rank results affect voting patterns. On the other end of the phone, he repeats one of the searches I did. He types “do blacks…” into Google.

“Look at that. I haven’t even hit a button and it’s automatically populated the page with answers to the query: ‘Do blacks commit more crimes?’ And look, I could have been going to ask all sorts of questions. ‘Do blacks excel at sports’, or anything. And it’s only given me two choices and these aren’t simply search-based or the most searched terms right now. Google used to use that but now they use an algorithm that looks at other things. Now, let me look at Bing and Yahoo. I’m on Yahoo and I have 10 suggestions, not one of which is ‘Do black people commit more crime?’

“And people don’t question this. Google isn’t just offering a suggestion. This is a negative suggestion and we know that negative suggestions depending on lots of things can draw between five and 15 more clicks. And this all programmed. And it could be programmed differently.”

What Epstein’s work has shown is that the contents of a page of search results can influence people’s views and opinions. The type and order of search rankings was shown to influence voters in India in double-blind trials. There were similar results relating to the search suggestions you are offered.

“The general public are completely in the dark about very fundamental issues regarding online search and influence. We are talking about the most powerful mind-control machine ever invented in the history of the human race. And people don’t even notice it.”

Damien Tambini, an associate professor at the London School of Economics, who focuses on media regulation, says that we lack any sort of framework to deal with the potential impact of these companies on the democratic process. “We have structures that deal with powerful media corporations. We have competition laws. But these companies are not being held responsible. There are no powers to get Google or Facebook to disclose anything. There’s an editorial function to Google and Facebook but it’s being done by sophisticated algorithms. They say it’s machines not editors. But that’s simply a mechanised editorial function.”

And the companies, says John Naughton, the Observer columnist and a senior research fellow at Cambridge University, are terrified of acquiring editorial responsibilities they don’t want. “Though they can and regularly do tweak the results in all sorts of ways.”

Certainly the results about Google on Google don’t seem entirely neutral. Google “Is Google racist?” and the featured result – the Google answer boxed out at the top of the page – is quite clear: no. It is not.

But the enormity and complexity of having two global companies of a kind we have never seen before influencing so many areas of our lives is such, says Naughton, that “we don’t even have the mental apparatus to even know what the problems are”.

And this is especially true of the future. Google and Facebook are at the forefront of AI. They are going to own the future. And the rest of us can barely start to frame the sorts of questions we ought to be asking. “Politicians don’t think long term. And corporations don’t think long term because they’re focused on the next quarterly results and that’s what makes Google and Facebook interesting and different. They are absolutely thinking long term. They have the resources, the money, and the ambition to do whatever they want.

“They want to digitise every book in the world: they do it. They want to build a self-driving car: they do it. The fact that people are reading about these fake news stories and realising that this could have an effect on politics and elections, it’s like, ‘Which planet have you been living on?’ For Christ’s sake, this is obvious.”

“The internet is among the few things that humans have built that they don’t understand.” It is “the largest experiment involving anarchy in history. Hundreds of millions of people are, each minute, creating and consuming an untold amount of digital content in an online world that is not truly bound by terrestrial laws.” The internet as a lawless anarchic state? A massive human experiment with no checks and balances and untold potential consequences? What kind of digital doom-mongerer would say such a thing? Step forward, Eric Schmidt – Google’s chairman. They are the first lines of the book, The New Digital Age, that he wrote with Jared Cohen.

We don’t understand it. It is not bound by terrestrial laws. And it’s in the hands of two massive, all-powerful corporations. It’s their experiment, not ours. The technology that was supposed to set us free may well have helped Trump to power, or covertly helped swing votes for Brexit. It has created a vast network of propaganda that has encroached like a cancer across the entire internet. This is a technology that has enabled the likes of Cambridge Analytica to create political messages uniquely tailored to you. They understand your emotional responses and how to trigger them. They know your likes, dislikes, where you live, what you eat, what makes you laugh, what makes you cry.

And what next? Rebecca MacKinnon’s research has shown how authoritarian regimes reshape the internet for their own purposes. Is that what’s going to happen with Silicon Valley and Trump? As Martin Moore points out, the president-elect claimed that Apple chief executive Tim Cook called to congratulate him soon after his election victory. “And there will undoubtedly be be pressure on them to collaborate,” says Moore.

Journalism is failing in the face of such change and is only going to fail further. New platforms have put a bomb under the financial model – advertising – resources are shrinking, traffic is increasingly dependent on them, and publishers have no access, no insight at all, into what these platforms are doing in their headquarters, their labs. And now they are moving beyond the digital world into the physical. The next frontiers are healthcare, transportation, energy. And just as Google is a near-monopoly for search, its ambition to own and control the physical infrastructure of our lives is what’s coming next. It already owns our data and with it our identity. What will it mean when it moves into all the other areas of our lives?

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg: still only 32 years of age. Photograph: Mariana Bazo/Reuters

“At the moment, there’s a distance when you Google ‘Jews are’ and get ‘Jews are evil’,” says Julia Powles, a researcher at Cambridge on technology and law. “But when you move into the physical realm, and these concepts become part of the tools being deployed when you navigate around your city or influence how people are employed, I think that has really pernicious consequences.”

Powles is shortly to publish a paper looking at DeepMind’s relationship with the NHS. “A year ago, 2 million Londoners’ NHS health records were handed over to DeepMind. And there was complete silence from politicians, from regulators, from anyone in a position of power. This is a company without any healthcare experience being given unprecedented access into the NHS and it took seven months to even know that they had the data. And that took investigative journalism to find it out.”

The headline was that DeepMind was going to work with the NHS to develop an app that would provide early warning for sufferers of kidney disease. And it is, but DeepMind’s ambitions – “to solve intelligence” – goes way beyond that. The entire history of 2 million NHS patients is, for artificial intelligence researchers, a treasure trove. And, their entry into the NHS – providing useful services in exchange for our personal data – is another massive step in their power and influence in every part of our lives.

Because the stage beyond search is prediction. Google wants to know what you want before you know yourself. “That’s the next stage,” says Martin Moore. “We talk about the omniscience of these tech giants, but that omniscience takes a huge step forward again if they are able to predict. And that’s where they want to go. To predict diseases in health. It’s really, really problematic.”

For the nearly 20 years that Google has been in existence, our view of the company has been inflected by the youth and liberal outlook of its founders. Ditto Facebook, whose mission, Zuckberg said, was not to be “a company. It was built to accomplish a social mission to make the world more open and connected.”

It would be interesting to know how he thinks that’s working out. Donald Trump is connecting through exactly the same technology platforms that supposedly helped fuel the Arab spring; connecting to racists and xenophobes. And Facebook and Google are amplifying and spreading that message. And us too – the mainstream media. Our outrage is just another node on Jonathan Albright’s data map.

“The more we argue with them, the more they know about us,” he says. “It all feeds into a circular system. What we’re seeing here is new era of network propaganda.”

We are all points on that map. And our complicity, our credulity, being consumers not concerned citizens, is an essential part of that process. And what happens next is down to us. “I would say that everybody has been really naive and we need to reset ourselves to a much more cynical place and proceed on that basis,” is Rebecca MacKinnon’s advice. “There is no doubt that where we are now is a very bad place. But it’s we as a society who have jointly created this problem. And if we want to get to a better place, when it comes to having an information ecosystem that serves human rights and democracy instead of destroying it, we have to share responsibility for that.”

Are Jews evil? How do you want that question answered? This is our internet. Not Google’s. Not Facebook’s. Not rightwing propagandists. And we’re the only ones who can reclaim it.