'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label credit. Show all posts

Showing posts with label credit. Show all posts

Monday, 1 April 2024

Thursday, 15 December 2022

The DWP has become Britain’s biggest debt collector.

Gordon Brown in The Guardian

Prime Minister Sunak talks about the need for “compassion” from the government this winter. But how far do social security benefits have to fall before our welfare system descends into a form of cruelty?

Take a couple with three children whose universal credit payment is, in theory, £46.11 a day. However, when their payment lands they have just £35, because around a quarter of their benefit has been deducted to pay back the loan they had to take out on joining universal credit to cover the five weeks they were denied benefit. And an extra 5% has been deducted as back payment to their utility company. According to Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) rules, money can be deducted for repayment of advance or emergency loans, and even on behalf of third parties for rent, utilities and service charge payments.

With gas and electricity likely to cost, at a minimum, £7 on cold days like today, and with a council tax contribution to be paid on top, they find that they have just £25. 80 a day left over, or £5.16 per person, to pay for food and all other essentials. Even if the Scottish child poverty payment comes their way, clothes, travel, toiletries and home furnishings remain out of reach. Parents like them are just about the best accountants I could ever meet , but you can’t budget with nothing to budget with. And that’s why so many have had to tell their children they can’t afford presents this Christmas. No wonder they need the weekly bag of food they get from the local food bank. But they also need a toiletries and hygiene bank, a clothes bank, a bedding bank, a home furnishings bank, and a baby bank.

The DWP has now become the country’s biggest debt collector, seizing money that should never have had to be paid back, from people who cannot afford to pay anyway. In fact, the majority of families on universal credit do not receive the full benefit that the DWP advertises. More than 20% is deducted at source from each benefit payment made to a million households, leaving them surviving on scraps and charity as they run out of cash in the days before their next payment. In total, 2 million children are in families suffering deductions.

Prime Minister Sunak talks about the need for “compassion” from the government this winter. But how far do social security benefits have to fall before our welfare system descends into a form of cruelty?

Take a couple with three children whose universal credit payment is, in theory, £46.11 a day. However, when their payment lands they have just £35, because around a quarter of their benefit has been deducted to pay back the loan they had to take out on joining universal credit to cover the five weeks they were denied benefit. And an extra 5% has been deducted as back payment to their utility company. According to Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) rules, money can be deducted for repayment of advance or emergency loans, and even on behalf of third parties for rent, utilities and service charge payments.

With gas and electricity likely to cost, at a minimum, £7 on cold days like today, and with a council tax contribution to be paid on top, they find that they have just £25. 80 a day left over, or £5.16 per person, to pay for food and all other essentials. Even if the Scottish child poverty payment comes their way, clothes, travel, toiletries and home furnishings remain out of reach. Parents like them are just about the best accountants I could ever meet , but you can’t budget with nothing to budget with. And that’s why so many have had to tell their children they can’t afford presents this Christmas. No wonder they need the weekly bag of food they get from the local food bank. But they also need a toiletries and hygiene bank, a clothes bank, a bedding bank, a home furnishings bank, and a baby bank.

The DWP has now become the country’s biggest debt collector, seizing money that should never have had to be paid back, from people who cannot afford to pay anyway. In fact, the majority of families on universal credit do not receive the full benefit that the DWP advertises. More than 20% is deducted at source from each benefit payment made to a million households, leaving them surviving on scraps and charity as they run out of cash in the days before their next payment. In total, 2 million children are in families suffering deductions.

Gordon Brown with workers at the Big Hoose multi-bank project, Fife, 8 November 2022. Photograph: Murdo MacLeod/The Guardian

When the money runs out, and the food bank tokens are gone, parents become desperate and ashamed that their children cannot be fed, and fall victim to loan sharks hiding in the back alleys who exploit hardship and compound it, and prey on pain and inflame it.

The case for each community having its own multi-bank – its reservoir of supplies for those without – is more urgent this winter than at any time I have known. Since the Trussell Trust’s brilliant expansion of UK food banks, creative local and national charities have pioneered community banks of all kinds offering free clothes, furnishings, bedding, electrical goods and, in the case of the national charity In Kind Direct, toiletries.

In Fife, Amazon, PepsiCo, Scotmid Fishers and other companies helped to set up a multi-bank. It’s a simple idea that could be replicated nationwide: they meet unmet needs by using unused goods. The companies have the goods people need, and the charities know the people who need them. With a coordinating charity, a warehouse to amass donations and a proper referral system, multi-banks can ensure their goods alleviate poverty.

But the charities know themselves that they can never do enough. With the state privatisations of gas, water, electricity and telecoms, the government gave up on responsibility for essential national assets. But now, with what is in effect the privatisation of welfare, our government is giving up on its responsibility to those in greatest need – passing the buck to charities, which cannot cope. Just as breadwinners cannot afford bread, food banks are running out of food.

Charities, too,are at the mercy of exceptionally high demand and the changing circumstances of donors whose help can be withdrawn as suddenly as it has been given. And so while voluntary organisations – and not the welfare state – are currently our last line of defence, the gap they have to bridge is too big for them to ever be the country’s safety net.

According to Prof Donald Hirsch and the team researching minimum income standards at Loughborough University, benefit levels for those out of work now fall 50% short of what most of us would think is a minimum living income, with their real value falling faster in 2022 than at any time for 50 years since up-ratings were introduced. And still 800,000 of the poorest children in England go without free school meals.

When the money runs out, and the food bank tokens are gone, parents become desperate and ashamed that their children cannot be fed, and fall victim to loan sharks hiding in the back alleys who exploit hardship and compound it, and prey on pain and inflame it.

The case for each community having its own multi-bank – its reservoir of supplies for those without – is more urgent this winter than at any time I have known. Since the Trussell Trust’s brilliant expansion of UK food banks, creative local and national charities have pioneered community banks of all kinds offering free clothes, furnishings, bedding, electrical goods and, in the case of the national charity In Kind Direct, toiletries.

In Fife, Amazon, PepsiCo, Scotmid Fishers and other companies helped to set up a multi-bank. It’s a simple idea that could be replicated nationwide: they meet unmet needs by using unused goods. The companies have the goods people need, and the charities know the people who need them. With a coordinating charity, a warehouse to amass donations and a proper referral system, multi-banks can ensure their goods alleviate poverty.

But the charities know themselves that they can never do enough. With the state privatisations of gas, water, electricity and telecoms, the government gave up on responsibility for essential national assets. But now, with what is in effect the privatisation of welfare, our government is giving up on its responsibility to those in greatest need – passing the buck to charities, which cannot cope. Just as breadwinners cannot afford bread, food banks are running out of food.

Charities, too,are at the mercy of exceptionally high demand and the changing circumstances of donors whose help can be withdrawn as suddenly as it has been given. And so while voluntary organisations – and not the welfare state – are currently our last line of defence, the gap they have to bridge is too big for them to ever be the country’s safety net.

According to Prof Donald Hirsch and the team researching minimum income standards at Loughborough University, benefit levels for those out of work now fall 50% short of what most of us would think is a minimum living income, with their real value falling faster in 2022 than at any time for 50 years since up-ratings were introduced. And still 800,000 of the poorest children in England go without free school meals.

---

I’m so cold I live in my bed – like the grandparents in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Marin

---

When it comes to helping with heating, the maximum that any family will receive, no matter its size, is £24 a week emergency help to cover what the government accepts is the £50 a week typical cost of heating a home. From April, the extra payments will be even less – just £16 to cover nearly the typical £60 a week they now expect gas and electricity to cost. And then, as Jeremy Hunt says, help with heating will become a thing of the past.

One hundred years ago, Winston Churchill was moved to talk of the unacceptable contrast between the accumulated excesses of unjustified privilege and “the gaping sorrows of the left-out millions”. Our long term priority must be to persuade a highly unequal country of the need for a decent minimum income for all, but our immediate demand must be for the government to suspend for the duration of this energy crisis the deductions that will soon cause destitution.

Ministers have been forced to change tack before. In April 2021 the government reduced the cap on the proportion of income deducted from 30% to 25%. During the first phase of Covid, ministers temporarily halted all deductions. In April, they discouraged utility firms from demanding them, but deductions as high as 30% of income are still commonplace.

There is no huge cost to the government in suspending deductions, for it will get its money back later. But this could be a lifesaver for millions now suffering under a regime that seems vindictive beyond austerity. Let this be a Christmas of compassion, instead of cruelty.

I’m so cold I live in my bed – like the grandparents in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Marin

---

When it comes to helping with heating, the maximum that any family will receive, no matter its size, is £24 a week emergency help to cover what the government accepts is the £50 a week typical cost of heating a home. From April, the extra payments will be even less – just £16 to cover nearly the typical £60 a week they now expect gas and electricity to cost. And then, as Jeremy Hunt says, help with heating will become a thing of the past.

One hundred years ago, Winston Churchill was moved to talk of the unacceptable contrast between the accumulated excesses of unjustified privilege and “the gaping sorrows of the left-out millions”. Our long term priority must be to persuade a highly unequal country of the need for a decent minimum income for all, but our immediate demand must be for the government to suspend for the duration of this energy crisis the deductions that will soon cause destitution.

Ministers have been forced to change tack before. In April 2021 the government reduced the cap on the proportion of income deducted from 30% to 25%. During the first phase of Covid, ministers temporarily halted all deductions. In April, they discouraged utility firms from demanding them, but deductions as high as 30% of income are still commonplace.

There is no huge cost to the government in suspending deductions, for it will get its money back later. But this could be a lifesaver for millions now suffering under a regime that seems vindictive beyond austerity. Let this be a Christmas of compassion, instead of cruelty.

Monday, 20 June 2022

Wednesday, 22 December 2021

Friday, 22 May 2020

What would negative interest rates mean for mortgages and savings?

Hilary Osborne in The Guardian

What happens to my mortgage?

If it’s a fixed-rate mortgage, nothing. And most households are on this type of deal – in recent years around nine in 10 new mortgages have been taken on a fixed rate.

If it is a variable-rate mortgage – a tracker, or a mortgage on or linked to a lender’s standard variable rate – the rate could fall a little if the base rate is cut. But the drop is likely to be limited by terms and conditions. David Hollingworth, of the mortgage brokers London & Country, says trackers sold very recently have in some cases had a “collar” that prevents the lender from having to cut the rate at all. Skipton building society, for example, has a tracker at 1.29 percentage points above the base rate that can only go up.

Older mortgages often have a minimum rate specified in the small print. Nationwide building society, for example, will never reduce the rate it tracks below 0% – so if your mortgage is at base rate plus 1 percentage points, it will never fall below 1%. Santander specifies in some mortgages that the lowest rate it will ever charge is 0.0001%.

You will need to dig out your paperwork to see how low your mortgage rate could go.

Will new mortgages be free?

In Denmark, mortgages with negative interest rates went on sale last year. Borrowers with Jyske Bank were lent money at a rate of -0.5%, which meant the sum they owed fell each month by more than the sum they had repaid. There is no reason why UK lenders could not follow suit, although so far there is no sign that any will.

In the meantime, fixed-rate mortgages are getting cheaper and may continue to fall in price. Big lenders including HSBC and Barclays have reduced fixed-rates this week and more may follow. Hollingworth says borrowers now have a choice of five-year fixed rates below 1.5%, with HSBC’s deal now at 1.39%.

Tracker mortgages have been pulled and repriced with larger margins, to cushion lenders against falling rates. If rates are cut again, expect more of that, as well as the collars already seen on some deals.

A negative base rate means banks and building societies have to pay to keep money on deposit, and it is designed to discourage them from doing so and make them keen to lend.

Fears over what might happen to property prices mean they are still likely to lend very carefully, but they should not need to restrict the range and number of mortgages on offer. Some lenders that reduced their maximum mortgages while they were unable to do valuations have started to offer loans on smaller deposits, although the choice of 90% loans is very limited. “Lenders do have appetite to lend,” says Hollingworth.

What happens to my savings?

Savings rates have already been hit by the two base rate cuts in March and most easy-access accounts from high street banks are already paying just 0.1% in interest.

Andrew Hagger, the founder of the financial information website Moneycomms, says he thinks it is unlikely banks will start charging people to hold their everyday savings. “Many would just withdraw cash and possibly keep it in the house, thus opening a can of worms around security and break-ins,” he says. “However, if the Bank of England did introduce negative rates, I’m sure we would see even more savings accounts heading towards zero.”

Rachel Springall, from the data firm Moneyfacts, says: “The most flexible savings accounts could face further cuts should base rate move any lower or if savings providers decide they want to deter deposits.”

She is not ruling out a charge for deposits. “Some savings accounts could go down this path – similar to how some banks charge a fee on a current account,” she says.

Wealthy savers are likely to be the first who would face a charge. Last year UBS started charging its ultra-rich clients a fee for cash savings of more than €500,000 (£449,000), starting at 0.6% a year and rising to 0.75% on larger deposits. And at the Danish Jyske Bank, similar charges apply.

“It could be that super-rich clients in the UK get charged a similar fee as the commercial banks may wish to discourage large cash holdings which they are having to pay for,” says Hagger.

What about loans and credit cards?

Personal loan rates are already low and are usually fixed, so you will not see your monthly repayments fall if rates go down. Credit card rates are usually low for new customers, but rise far above the base rate once introductory periods have ended, so will not be anywhere close to falling into negative territory.

Hagger says he does not expect card or loan rates to plummet in the near future, “as I think banks will continue to tighten their credit underwriting – I think they’ll be more concerned about rising bad debt levels due to a surge in unemployment, for the remainder of 2020 at least.”

This month Virgin Money closed the credit card accounts of 32,000 borrowers after carrying out “routine affordability checks”. It later reversed the decision, but this could be a sign that lenders are reviewing their customer bases and trying to reduce their risk.

You will need to dig out your paperwork to see how low your mortgage rate could go. Photograph: Joe Giddens/PA

The governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, has paved the way for negative interest rates, saying officials are actively considering all options to prop up the economy.

The Bank’s base rate stands at 0.1%, the lowest level on record, so it would not take much to take it into negative territory. The UK would not be the first country to have a negative rate at its central bank – Japan and Sweden are among those that have done so.

The governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, has paved the way for negative interest rates, saying officials are actively considering all options to prop up the economy.

The Bank’s base rate stands at 0.1%, the lowest level on record, so it would not take much to take it into negative territory. The UK would not be the first country to have a negative rate at its central bank – Japan and Sweden are among those that have done so.

What happens to my mortgage?

If it’s a fixed-rate mortgage, nothing. And most households are on this type of deal – in recent years around nine in 10 new mortgages have been taken on a fixed rate.

If it is a variable-rate mortgage – a tracker, or a mortgage on or linked to a lender’s standard variable rate – the rate could fall a little if the base rate is cut. But the drop is likely to be limited by terms and conditions. David Hollingworth, of the mortgage brokers London & Country, says trackers sold very recently have in some cases had a “collar” that prevents the lender from having to cut the rate at all. Skipton building society, for example, has a tracker at 1.29 percentage points above the base rate that can only go up.

Older mortgages often have a minimum rate specified in the small print. Nationwide building society, for example, will never reduce the rate it tracks below 0% – so if your mortgage is at base rate plus 1 percentage points, it will never fall below 1%. Santander specifies in some mortgages that the lowest rate it will ever charge is 0.0001%.

You will need to dig out your paperwork to see how low your mortgage rate could go.

Will new mortgages be free?

In Denmark, mortgages with negative interest rates went on sale last year. Borrowers with Jyske Bank were lent money at a rate of -0.5%, which meant the sum they owed fell each month by more than the sum they had repaid. There is no reason why UK lenders could not follow suit, although so far there is no sign that any will.

In the meantime, fixed-rate mortgages are getting cheaper and may continue to fall in price. Big lenders including HSBC and Barclays have reduced fixed-rates this week and more may follow. Hollingworth says borrowers now have a choice of five-year fixed rates below 1.5%, with HSBC’s deal now at 1.39%.

Tracker mortgages have been pulled and repriced with larger margins, to cushion lenders against falling rates. If rates are cut again, expect more of that, as well as the collars already seen on some deals.

A negative base rate means banks and building societies have to pay to keep money on deposit, and it is designed to discourage them from doing so and make them keen to lend.

Fears over what might happen to property prices mean they are still likely to lend very carefully, but they should not need to restrict the range and number of mortgages on offer. Some lenders that reduced their maximum mortgages while they were unable to do valuations have started to offer loans on smaller deposits, although the choice of 90% loans is very limited. “Lenders do have appetite to lend,” says Hollingworth.

What happens to my savings?

Savings rates have already been hit by the two base rate cuts in March and most easy-access accounts from high street banks are already paying just 0.1% in interest.

Andrew Hagger, the founder of the financial information website Moneycomms, says he thinks it is unlikely banks will start charging people to hold their everyday savings. “Many would just withdraw cash and possibly keep it in the house, thus opening a can of worms around security and break-ins,” he says. “However, if the Bank of England did introduce negative rates, I’m sure we would see even more savings accounts heading towards zero.”

Rachel Springall, from the data firm Moneyfacts, says: “The most flexible savings accounts could face further cuts should base rate move any lower or if savings providers decide they want to deter deposits.”

She is not ruling out a charge for deposits. “Some savings accounts could go down this path – similar to how some banks charge a fee on a current account,” she says.

Wealthy savers are likely to be the first who would face a charge. Last year UBS started charging its ultra-rich clients a fee for cash savings of more than €500,000 (£449,000), starting at 0.6% a year and rising to 0.75% on larger deposits. And at the Danish Jyske Bank, similar charges apply.

“It could be that super-rich clients in the UK get charged a similar fee as the commercial banks may wish to discourage large cash holdings which they are having to pay for,” says Hagger.

What about loans and credit cards?

Personal loan rates are already low and are usually fixed, so you will not see your monthly repayments fall if rates go down. Credit card rates are usually low for new customers, but rise far above the base rate once introductory periods have ended, so will not be anywhere close to falling into negative territory.

Hagger says he does not expect card or loan rates to plummet in the near future, “as I think banks will continue to tighten their credit underwriting – I think they’ll be more concerned about rising bad debt levels due to a surge in unemployment, for the remainder of 2020 at least.”

This month Virgin Money closed the credit card accounts of 32,000 borrowers after carrying out “routine affordability checks”. It later reversed the decision, but this could be a sign that lenders are reviewing their customer bases and trying to reduce their risk.

Thursday, 19 September 2019

Why rigged capitalism is damaging liberal democracy

Economies are not delivering for most citizens because of weak competition, feeble productivity growth and tax loopholes writes Martin Wolf in The FT

“While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders.”

With this sentence, the US Business Roundtable, which represents the chief executives of 181 of the world’s largest companies, abandoned their longstanding view that “corporations exist principally to serve their shareholders”.

This is certainly a moment. But what does — and should — that moment mean? The answer needs to start with acknowledgment of the fact that something has gone very wrong. Over the past four decades, and especially in the US, the most important country of all, we have observed an unholy trinity of slowing productivity growth, soaring inequality and huge financial shocks.

As Jason Furman of Harvard University and Peter Orszag of Lazard Frères noted in a paper last year: “From 1948 to 1973, real median family income in the US rose 3 per cent annually. At this rate . . . there was a 96 per cent chance that a child would have a higher income than his or her parents. Since 1973, the median family has seen its real income grow only 0.4 per cent annually . . . As a result, 28 per cent of children have lower income than their parents did.”

So why is the economy not delivering? The answer lies, in large part, with the rise of rentier capitalism. In this case “rent” means rewards over and above those required to induce the desired supply of goods, services, land or labour. “Rentier capitalism” means an economy in which market and political power allows privileged individuals and businesses to extract a great deal of such rent from everybody else.

That does not explain every disappointment. As Robert Gordon, professor of social sciences at Northwestern University, argues, fundamental innovation slowed after the mid-20th century. Technology has also created greater reliance on graduates and raised their relative wages, explaining part of the rise of inequality. But the share of the top 1 per cent of US earners in pre-tax income jumped from 11 per cent in 1980 to 20 per cent in 2014. This was not mainly the result of such skill-biased technological change.

If one listens to the political debates in many countries, notably the US and UK, one would conclude that the disappointment is mainly the fault of imports from China or low-wage immigrants, or both. Foreigners are ideal scapegoats. But the notion that rising inequality and slow productivity growth are due to foreigners is simply false.

Every western high-income country trades more with emerging and developing countries today than it did four decades ago. Yet increases in inequality have varied substantially. The outcome depended on how the institutions of the market economy behaved and on domestic policy choices.

Harvard economist Elhanan Helpman ends his overview of a huge academic literature on the topic with the conclusion that “globalisation in the form of foreign trade and offshoring has not been a large contributor to rising inequality. Multiple studies of different events around the world point to this conclusion.”

The shift in the location of much manufacturing, principally to China, may have lowered investment in high-income economies a little. But this effect cannot have been powerful enough to reduce productivity growth significantly. To the contrary, the shift in the global division of labour induced high-income economies to specialise in skill-intensive sectors, where there was more potential for fast productivity growth.

Donald Trump, a naive mercantilist, focuses, instead, on bilateral trade imbalances as a cause of job losses. These deficits reflect bad trade deals, the American president insists. It is true that the US has overall trade deficits, while the EU has surpluses. But their trade policies are quite similar. Trade policies do not explain bilateral balances. Bilateral balances, in turn, do not explain overall balances. The latter are macroeconomic phenomena. Both theory and evidence concur on this.

The economic impact of immigration has also been small, however big the political and cultural “shock of the foreigner” may be. Research strongly suggests that the effect of immigration on the real earnings of the native population and on receiving countries’ fiscal position has been small and frequently positive.

Far more productive than this politically rewarding, but mistaken, focus on the damage done by trade and migration is an examination of contemporary rentier capitalism itself.

Finance plays a key role, with several dimensions. Liberalised finance tends to metastasise, like a cancer. Thus, the financial sector’s ability to create credit and money finances its own activities, incomes and (often illusory) profits.

A 2015 study by Stephen Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi for the Bank for International Settlements said “the level of financial development is good only up to a point, after which it becomes a drag on growth, and that a fast-growing financial sector is detrimental to aggregate productivity growth”. When the financial sector grows quickly, they argue, it hires talented people. These then lend against property, because it generates collateral. This is a diversion of talented human resources in unproductive, useless directions.

Again, excessive growth of credit almost always leads to crises, as Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff showed in This Time is Different. This is why no modern government dares let the supposedly market-driven financial sector operate unaided and unguided. But that in turn creates huge opportunities to gain from irresponsibility: heads, they win; tails, the rest of us lose. Further crises are guaranteed.

Finance also creates rising inequality. Thomas Philippon of the Stern School of Business and Ariell Reshef of the Paris School of Economics showed that the relative earnings of finance professionals exploded upwards in the 1980s with the deregulation of finance. They estimated that “rents” — earnings over and above those needed to attract people into the industry — accounted for 30-50 per cent of the pay differential between finance professionals and the rest of the private sector.

This explosion of financial activity since 1980 has not raised the growth of productivity. If anything, it has lowered it, especially since the crisis. The same is true of the explosion in pay of corporate management, yet another form of rent extraction. As Deborah Hargreaves, founder of the High Pay Centre, notes, in the UK the ratio of average chief executive pay to that of average workers rose from 48 to one in 1998 to 129 to one in 2016. In the US, the same ratio rose from 42 to one in 1980 to 347 to one in 2017.

As the US essayist HL Mencken wrote: “For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong.” Pay linked to the share price gave management a huge incentive to raise that price, by manipulating earnings or borrowing money to buy the shares. Neither adds value to the company. But they can add a great deal of wealth to management. A related problem with governance is conflicts of interest, notably over independence of auditors.

In sum, personal financial considerations permeate corporate decision-making. As the independent economist Andrew Smithers argues in Productivity and the Bonus Culture, this comes at the expense of corporate investment and so of long-run productivity growth.

A possibly still more fundamental issue is the decline of competition. Mr Furman and Mr Orszag say there is evidence of increased market concentration in the US, a lower rate of entry of new firms and a lower share of young firms in the economy compared with three or four decades ago. Work by the OECD and Oxford Martin School also notes widening gaps in productivity and profit mark-ups between the leading businesses and the rest. This suggests weakening competition and rising monopoly rent. Moreover, a great deal of the increase in inequality arises from radically different rewards for workers with similar skills in different firms: this, too, is a form of rent extraction.

A part of the explanation for weaker competition is “winner-takes-almost-all” markets: superstar individuals and their companies earn monopoly rents, because they can now serve global markets so cheaply. The network externalities — benefits of using a network that others are using — and zero marginal costs of platform monopolies (Facebook, Google, Amazon, Alibaba and Tencent) are the dominant examples.

Another such natural force is the network externalities of agglomerations, stressed by Paul Collier in The Future of Capitalism. Successful metropolitan areas — London, New York, the Bay Area in California — generate powerful feedback loops, attracting and rewarding talented people. This disadvantages businesses and people trapped in left-behind towns. Agglomerations, too, create rents, not just in property prices, but also in earnings.

Yet monopoly rent is not just the product of such natural — albeit worrying — economic forces. It is also the result of policy. In the US, Yale University law professor Robert Bork argued in the 1970s that “consumer welfare” should be the sole objective of antitrust policy. As with shareholder value maximisation, this oversimplified highly complex issues. In this case, it led to complacency about monopoly power, provided prices stayed low. Yet tall trees deprive saplings of the light they need to grow. So, too, may giant companies.

Some might argue, complacently, that the “monopoly rent” we now see in leading economies is largely a sign of the “creative destruction” lauded by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. In fact, we are not seeing enough creation, destruction or productivity growth to support that view convincingly.

A disreputable aspect of rent-seeking is radical tax avoidance. Corporations (and so also shareholders) benefit from the public goods — security, legal systems, infrastructure, educated workforces and sociopolitical stability — provided by the world’s most powerful liberal democracies. Yet they are also in a perfect position to exploit tax loopholes, especially those companies whose location of production or innovation is difficult to determine.

The biggest challenges within the corporate tax system are tax competition and base erosion and profit shifting. We see the former in falling tax rates. We see the latter in the location of intellectual property in tax havens, in charging tax-deductible debt against profits accruing in higher-tax jurisdictions and in rigging transfer prices within firms.

A 2015 study by the IMF calculated that base erosion and profit shifting reduced long-run annual revenue in OECD countries by about $450bn (1 per cent of gross domestic product) and in non-OECD countries by slightly over $200bn (1.3 per cent of GDP). These are significant figures in the context of a tax that raised an average of only 2.9 per cent of GDP in 2016 in OECD countries and just 2 per cent in the US.

Brad Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations shows that US corporations report seven times as much profit in small tax havens (Bermuda, the British Caribbean, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Singapore and Switzerland) as in six big economies (China, France, Germany, India, Italy and Japan). This is ludicrous. The tax reform under Mr Trump changed essentially nothing. Needless to say, not only US corporations benefit from such loopholes.

In such cases, rents are not merely being exploited. They are being created, through lobbying for distorting and unfair tax loopholes and against needed regulation of mergers, anti-competitive practices, financial misbehaviour, the environment and labour markets. Corporate lobbying overwhelms the interests of ordinary citizens. Indeed, some studies suggest that the wishes of ordinary people count for next to nothing in policymaking.

Not least, as some western economies have become more Latin American in their distribution of incomes, their politics have also become more Latin American. Some of the new populists are considering radical, but necessary, changes in competition, regulatory and tax policies. But others rely on xenophobic dog whistles while continuing to promote a capitalism rigged to favour a small elite. Such activities could well end up with the death of liberal democracy itself.

Members of the Business Roundtable and their peers have tough questions to ask themselves. They are right: seeking to maximise shareholder value has proved a doubtful guide to managing corporations. But that realisation is the beginning, not the end. They need to ask themselves what this understanding means for how they set their own pay and how they exploit — indeed actively create — tax and regulatory loopholes.

They must, not least, consider their activities in the public arena. What are they doing to ensure better laws governing the structure of the corporation, a fair and effective tax system, a safety net for those afflicted by economic forces beyond their control, a healthy local and global environment and a democracy responsive to the wishes of a broad majority?

We need a dynamic capitalist economy that gives everybody a justified belief that they can share in the benefits. What we increasingly seem to have instead is an unstable rentier capitalism, weakened competition, feeble productivity growth, high inequality and, not coincidentally, an increasingly degraded democracy. Fixing this is a challenge for us all, but especially for those who run the world’s most important businesses. The way our economic and political systems work must change, or they will perish.

“While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders.”

With this sentence, the US Business Roundtable, which represents the chief executives of 181 of the world’s largest companies, abandoned their longstanding view that “corporations exist principally to serve their shareholders”.

This is certainly a moment. But what does — and should — that moment mean? The answer needs to start with acknowledgment of the fact that something has gone very wrong. Over the past four decades, and especially in the US, the most important country of all, we have observed an unholy trinity of slowing productivity growth, soaring inequality and huge financial shocks.

As Jason Furman of Harvard University and Peter Orszag of Lazard Frères noted in a paper last year: “From 1948 to 1973, real median family income in the US rose 3 per cent annually. At this rate . . . there was a 96 per cent chance that a child would have a higher income than his or her parents. Since 1973, the median family has seen its real income grow only 0.4 per cent annually . . . As a result, 28 per cent of children have lower income than their parents did.”

So why is the economy not delivering? The answer lies, in large part, with the rise of rentier capitalism. In this case “rent” means rewards over and above those required to induce the desired supply of goods, services, land or labour. “Rentier capitalism” means an economy in which market and political power allows privileged individuals and businesses to extract a great deal of such rent from everybody else.

That does not explain every disappointment. As Robert Gordon, professor of social sciences at Northwestern University, argues, fundamental innovation slowed after the mid-20th century. Technology has also created greater reliance on graduates and raised their relative wages, explaining part of the rise of inequality. But the share of the top 1 per cent of US earners in pre-tax income jumped from 11 per cent in 1980 to 20 per cent in 2014. This was not mainly the result of such skill-biased technological change.

If one listens to the political debates in many countries, notably the US and UK, one would conclude that the disappointment is mainly the fault of imports from China or low-wage immigrants, or both. Foreigners are ideal scapegoats. But the notion that rising inequality and slow productivity growth are due to foreigners is simply false.

Every western high-income country trades more with emerging and developing countries today than it did four decades ago. Yet increases in inequality have varied substantially. The outcome depended on how the institutions of the market economy behaved and on domestic policy choices.

Harvard economist Elhanan Helpman ends his overview of a huge academic literature on the topic with the conclusion that “globalisation in the form of foreign trade and offshoring has not been a large contributor to rising inequality. Multiple studies of different events around the world point to this conclusion.”

The shift in the location of much manufacturing, principally to China, may have lowered investment in high-income economies a little. But this effect cannot have been powerful enough to reduce productivity growth significantly. To the contrary, the shift in the global division of labour induced high-income economies to specialise in skill-intensive sectors, where there was more potential for fast productivity growth.

Donald Trump, a naive mercantilist, focuses, instead, on bilateral trade imbalances as a cause of job losses. These deficits reflect bad trade deals, the American president insists. It is true that the US has overall trade deficits, while the EU has surpluses. But their trade policies are quite similar. Trade policies do not explain bilateral balances. Bilateral balances, in turn, do not explain overall balances. The latter are macroeconomic phenomena. Both theory and evidence concur on this.

The economic impact of immigration has also been small, however big the political and cultural “shock of the foreigner” may be. Research strongly suggests that the effect of immigration on the real earnings of the native population and on receiving countries’ fiscal position has been small and frequently positive.

Far more productive than this politically rewarding, but mistaken, focus on the damage done by trade and migration is an examination of contemporary rentier capitalism itself.

Finance plays a key role, with several dimensions. Liberalised finance tends to metastasise, like a cancer. Thus, the financial sector’s ability to create credit and money finances its own activities, incomes and (often illusory) profits.

A 2015 study by Stephen Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi for the Bank for International Settlements said “the level of financial development is good only up to a point, after which it becomes a drag on growth, and that a fast-growing financial sector is detrimental to aggregate productivity growth”. When the financial sector grows quickly, they argue, it hires talented people. These then lend against property, because it generates collateral. This is a diversion of talented human resources in unproductive, useless directions.

Again, excessive growth of credit almost always leads to crises, as Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff showed in This Time is Different. This is why no modern government dares let the supposedly market-driven financial sector operate unaided and unguided. But that in turn creates huge opportunities to gain from irresponsibility: heads, they win; tails, the rest of us lose. Further crises are guaranteed.

Finance also creates rising inequality. Thomas Philippon of the Stern School of Business and Ariell Reshef of the Paris School of Economics showed that the relative earnings of finance professionals exploded upwards in the 1980s with the deregulation of finance. They estimated that “rents” — earnings over and above those needed to attract people into the industry — accounted for 30-50 per cent of the pay differential between finance professionals and the rest of the private sector.

This explosion of financial activity since 1980 has not raised the growth of productivity. If anything, it has lowered it, especially since the crisis. The same is true of the explosion in pay of corporate management, yet another form of rent extraction. As Deborah Hargreaves, founder of the High Pay Centre, notes, in the UK the ratio of average chief executive pay to that of average workers rose from 48 to one in 1998 to 129 to one in 2016. In the US, the same ratio rose from 42 to one in 1980 to 347 to one in 2017.

As the US essayist HL Mencken wrote: “For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong.” Pay linked to the share price gave management a huge incentive to raise that price, by manipulating earnings or borrowing money to buy the shares. Neither adds value to the company. But they can add a great deal of wealth to management. A related problem with governance is conflicts of interest, notably over independence of auditors.

In sum, personal financial considerations permeate corporate decision-making. As the independent economist Andrew Smithers argues in Productivity and the Bonus Culture, this comes at the expense of corporate investment and so of long-run productivity growth.

A possibly still more fundamental issue is the decline of competition. Mr Furman and Mr Orszag say there is evidence of increased market concentration in the US, a lower rate of entry of new firms and a lower share of young firms in the economy compared with three or four decades ago. Work by the OECD and Oxford Martin School also notes widening gaps in productivity and profit mark-ups between the leading businesses and the rest. This suggests weakening competition and rising monopoly rent. Moreover, a great deal of the increase in inequality arises from radically different rewards for workers with similar skills in different firms: this, too, is a form of rent extraction.

A part of the explanation for weaker competition is “winner-takes-almost-all” markets: superstar individuals and their companies earn monopoly rents, because they can now serve global markets so cheaply. The network externalities — benefits of using a network that others are using — and zero marginal costs of platform monopolies (Facebook, Google, Amazon, Alibaba and Tencent) are the dominant examples.

Another such natural force is the network externalities of agglomerations, stressed by Paul Collier in The Future of Capitalism. Successful metropolitan areas — London, New York, the Bay Area in California — generate powerful feedback loops, attracting and rewarding talented people. This disadvantages businesses and people trapped in left-behind towns. Agglomerations, too, create rents, not just in property prices, but also in earnings.

Yet monopoly rent is not just the product of such natural — albeit worrying — economic forces. It is also the result of policy. In the US, Yale University law professor Robert Bork argued in the 1970s that “consumer welfare” should be the sole objective of antitrust policy. As with shareholder value maximisation, this oversimplified highly complex issues. In this case, it led to complacency about monopoly power, provided prices stayed low. Yet tall trees deprive saplings of the light they need to grow. So, too, may giant companies.

Some might argue, complacently, that the “monopoly rent” we now see in leading economies is largely a sign of the “creative destruction” lauded by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. In fact, we are not seeing enough creation, destruction or productivity growth to support that view convincingly.

A disreputable aspect of rent-seeking is radical tax avoidance. Corporations (and so also shareholders) benefit from the public goods — security, legal systems, infrastructure, educated workforces and sociopolitical stability — provided by the world’s most powerful liberal democracies. Yet they are also in a perfect position to exploit tax loopholes, especially those companies whose location of production or innovation is difficult to determine.

The biggest challenges within the corporate tax system are tax competition and base erosion and profit shifting. We see the former in falling tax rates. We see the latter in the location of intellectual property in tax havens, in charging tax-deductible debt against profits accruing in higher-tax jurisdictions and in rigging transfer prices within firms.

A 2015 study by the IMF calculated that base erosion and profit shifting reduced long-run annual revenue in OECD countries by about $450bn (1 per cent of gross domestic product) and in non-OECD countries by slightly over $200bn (1.3 per cent of GDP). These are significant figures in the context of a tax that raised an average of only 2.9 per cent of GDP in 2016 in OECD countries and just 2 per cent in the US.

Brad Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations shows that US corporations report seven times as much profit in small tax havens (Bermuda, the British Caribbean, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Singapore and Switzerland) as in six big economies (China, France, Germany, India, Italy and Japan). This is ludicrous. The tax reform under Mr Trump changed essentially nothing. Needless to say, not only US corporations benefit from such loopholes.

In such cases, rents are not merely being exploited. They are being created, through lobbying for distorting and unfair tax loopholes and against needed regulation of mergers, anti-competitive practices, financial misbehaviour, the environment and labour markets. Corporate lobbying overwhelms the interests of ordinary citizens. Indeed, some studies suggest that the wishes of ordinary people count for next to nothing in policymaking.

Not least, as some western economies have become more Latin American in their distribution of incomes, their politics have also become more Latin American. Some of the new populists are considering radical, but necessary, changes in competition, regulatory and tax policies. But others rely on xenophobic dog whistles while continuing to promote a capitalism rigged to favour a small elite. Such activities could well end up with the death of liberal democracy itself.

Members of the Business Roundtable and their peers have tough questions to ask themselves. They are right: seeking to maximise shareholder value has proved a doubtful guide to managing corporations. But that realisation is the beginning, not the end. They need to ask themselves what this understanding means for how they set their own pay and how they exploit — indeed actively create — tax and regulatory loopholes.

They must, not least, consider their activities in the public arena. What are they doing to ensure better laws governing the structure of the corporation, a fair and effective tax system, a safety net for those afflicted by economic forces beyond their control, a healthy local and global environment and a democracy responsive to the wishes of a broad majority?

We need a dynamic capitalist economy that gives everybody a justified belief that they can share in the benefits. What we increasingly seem to have instead is an unstable rentier capitalism, weakened competition, feeble productivity growth, high inequality and, not coincidentally, an increasingly degraded democracy. Fixing this is a challenge for us all, but especially for those who run the world’s most important businesses. The way our economic and political systems work must change, or they will perish.

Monday, 20 November 2017

The rise of dynamic and personalised pricing

Tim Walker in The Guardian

You wait 24 hours to book that flight, only to find it’s gone up by £100. You wait until Black Friday to buy that leather jacket and, sure enough, it’s been marked down. Today’s consumers are getting comfortable with the idea that prices online can fluctuate, not just at sale time, but several times over the course of a single day. Anyone who has booked a holiday on the internet is familiar with the concept, if not with its name. It’s known as dynamic pricing: when the cost of goods or services ebbs and flows in response to the slightest shifts in supply and demand, be it fresh croissants in the morning, a bargain TV or an Uber during a late-night “surge”.

Sports teams, entertainment venues and theme parks have started to use dynamic pricing methods, too, taking their cues from airlines and hotels to calibrate a range of ticketing deals that ensure they fill as many seats as possible. Last month, Regal, the US cinema chain, announced it would trial a form of dynamic ticket pricing at many of its multiplexes in 2018, in the hope of boosting its box office revenue. Digonex, one of the leading dynamic ticketing firms in the US, has consulted for Derby County and Manchester City football clubs in the UK. “In five years, dynamic pricing will be common practice in the attractions space,” says the company’s CEO, Greg Loewen. “The same goes for many other industries: movies, parking, tour operators.” Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, tweaks countless prices every day. Savvy shoppers have learned to wait for bargains with the help of other sites such as CamelCamelCamel.com, which analyses Amazon price drops and lists the biggest. On a single day on Amazon.co.uk last week, those included a Samsung Galaxy S7 phone, down 14% from £510.29 to £439, and a pack of six 300g jars of Ovaltine, down 33% from £17.94 to £12.

Physical retailers can’t match the agility of their online rivals, not least because changing prices requires altering labels. But “smart shelves” – already common in European supermarkets – are coming to the UK, with digital price displays that allow retailers to offer deals at different times of day, along with information about the products. Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and Tesco have all trialled electronic pricing systems in select stores. Marks & Spencer conducted an electronic pricing experiment last year, selling sandwiches more cheaply during the morning rush hour to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early.

Toby Pickard, senior innovations and trends analyst at the grocery research firm IGD, says this new technology will benefit retailers by enabling them “to gain more data about the products they sell; for example, they can closely gauge how prices fluctuating throughout the day may alter shoppers’ purchasing habits, or if on-shelf digital product reviews increase sales.” IGD’s research suggests there is an appetite for this sort of tech from consumers, too. For example, says Pickard: “Four in 10 shoppers say they are interested in being alerted to offers on their phone while in-store.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest M&S experimented with pricing to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early. Photograph: Luke Johnson/Commissioned for The Guardian

Earlier this year, the Luxembourg-based computer firm SES took a majority stake in the Irish software firm MarketHub. Together, they are bringing data analysis and smart-shelf-style systems to some 14,000 stores in 54 countries including the UK. MarketHub says two Spar stores in London have succeeded in raising revenue and decreasing waste since introducing its technology. For the firm’s CEO Roy Horgan, though, there’s a big difference between what MarketHub offers and dynamic pricing per se. “I don’t see dynamic pricing happening in major retailers,” he says. “Supermarkets have huge, complicated logistics systems. They can’t react in real time to what’s going in their stores the way Amazon can. [Physical retailers] want to discount, to have more relevant deals, fewer promotions, better value and more customer loyalty. That’s not about changing the price of individual products, it’s more about changing deals.”

As examples, Horgan suggests offering cheap lunch deals in the morning (à la M&S), so that workers don’t have to queue up at lunchtime, or guiding shoppers with limited budgets to discounted ingredients for an evening meal. “That’s not dynamic pricing,” he says. “It’s just agile retail.”

A recent survey of US consumers by Retail Systems Research (RSR) found that 71% didn’t care for the idea of dynamic pricing, though millennials were more amenable to the concept, with 14% of younger shoppers saying they “loved” it. Perhaps that ought not to be surprising, given the younger generation’s greater familiarity with browsing for bargains online.

“Consumers always love it when they can get a great deal, and dynamic pricing isn’t just about raising prices – it often leads to lowering them,” says Loewen. “In general, we have found that when prices are transparent to consumers and they understand the ‘rules of the game’, they adapt to dynamic pricing fairly seamlessly and even embrace it.”

Simon Read, a money and personal finance writer, says: “If you’re desperate for an item and it’s the last available, you are likely to pay a premium when dynamic pricing comes into play.” But dynamic pricing can also play to the consumer’s benefit, he explains.

“The truth is that retailers want to flog their wares at whatever price they can get. If you want to take advantage of dynamic pricing, you’ll need to find out when retailers are desperate to sell. In bricks-and-mortar stores that means shopping at quiet times – in the morning – or waiting until closing time when grocers need to clear their shelves.” If you’re shopping online, Read says, research the normal price of an item before buying it, so as not to be caught out. “It’s also a good idea to leave things in your shopping basket at most online retailers rather than buying immediately. After a day or two, you will often get an email offering a decent reduction.”

Those consumers who are suspicious of dynamic pricing may also be confusing it with (the far more controversial) personalised pricing, whereby specific customers are asked to pay different amounts for the same product, tailored to what the retailer thinks they can and will spend – using personal data points that might one day include, for instance, our credit rating. In 2014, the US Department of Transportation approved a system allowing airlines and travel companies to collect passengers’ data to present them with “personalised offerings” based on their address, their marital status, their birthday and their travel history. It’s not hard to imagine that the fares you are offered might be higher than for others if, say, you live in an affluent postcode and your husband’s birthday is coming up.

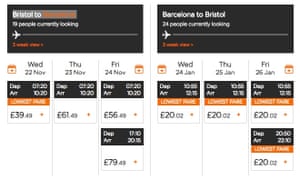

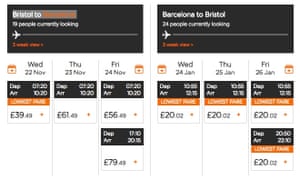

Airlines use dynamic pricing on flight tickets. Photograph: Easyjet

In 2012, the travel site Orbitz was found to be adjusting its prices for users of Apple Mac computers, after finding that they were prepared to spend up to 30% more on hotel rooms than other customers. That same year, the Wall Street Journal revealed that the Staples website offered products at different pricesdepending on the user’s proximity to rival stores. In 2014, a study conducted by Northeastern University in Boston found that several major e-commerce sites such as Home Depot and Walmart were manipulating prices based on the browsing history of individual customers. “Most people assume the internet is a neutral environment like the high street, where the price you see is the same as the one everyone else sees,” says Ariel Ezrachi, director of the University of Oxford Centre for Competition Law and Policy. “But on the high street you’re anonymous; online, the seller has information about you, and about your other buying options.”

Dynamic pricing, says Ezrachi, is simply a way for businesses to respond nimbly to market trends, and thus is within the bounds of what consumers already accept as market dynamics. “Personalised pricing is much more problematic. It’s based on asymmetricity of information; it’s only possible because the shopper doesn’t know what information the seller has about them, and because the seller is able to create an environment where the shopper believes they are seeing the market price.”

The ethics of pricing based on an individual’s personal data are vexed: some consumers will find it manipulative and insist on its regulation; others may feel it’s fair – socially beneficial, even – to charge wealthy customers more for a product or service. “You will find people arguing in different directions,” Ezrachi says. Loyalty cards have long enabled supermarkets and other major retailers to offer personalised offers based on the spending habits of repeat customers. B&Q has tested electronic price tags that display different prices to different customers using information gleaned from their phones (the company made clear that their intention was to “reward regular customers with discounts”, not to raise the price for more profligate shoppers). In the US, Coca-Cola and Albertsons supermarkets have experimented with targeting shoppers in-store by sending personalised offers to their phones when they approach the soft drinks aisle in an Albertsons store.

Horgan resists the idea that supermarkets will embrace personalised pricing. “In the airline industry, we have more freedom, information and choice on airlines than we’ve ever had before, and that is all dynamic-pricing led. But nobody’s loyal to Ryanair; they’re loyal to the deal. Retail is different,” he says. “If I have five pounds in my pocket and a family of four to feed, I want to know I can generate a recipe that is nutritious for them, and I want an app that can navigate me around the store to find a deal on [the necessary ingredients]. To me, that is personalised retail. But any [bricks and mortar] retailer who charges different prices to different people for the same product is an idiot. They’re only going to lose loyalty.”

Loewen agrees that personalised pricing carries as many dangers as opportunities for retailers. “Consumers are more empowered and informed than ever before, and any pricing strategy that seeks to fool or mislead them is unlikely to be successful for long,” he says. Nevertheless, in the dawning era of dynamic pricing, personalised pricing and agile retailing, the days of fixed prices seem to be coming to an end. And although the technology may be more advanced, in some ways dynamic pricing is simply a return to the days long before supermarkets, when traders would judge how high or low a price to haggle from a customer based on factors as simple as the sound of their accent, or the cut of their cloak.

You wait 24 hours to book that flight, only to find it’s gone up by £100. You wait until Black Friday to buy that leather jacket and, sure enough, it’s been marked down. Today’s consumers are getting comfortable with the idea that prices online can fluctuate, not just at sale time, but several times over the course of a single day. Anyone who has booked a holiday on the internet is familiar with the concept, if not with its name. It’s known as dynamic pricing: when the cost of goods or services ebbs and flows in response to the slightest shifts in supply and demand, be it fresh croissants in the morning, a bargain TV or an Uber during a late-night “surge”.

Sports teams, entertainment venues and theme parks have started to use dynamic pricing methods, too, taking their cues from airlines and hotels to calibrate a range of ticketing deals that ensure they fill as many seats as possible. Last month, Regal, the US cinema chain, announced it would trial a form of dynamic ticket pricing at many of its multiplexes in 2018, in the hope of boosting its box office revenue. Digonex, one of the leading dynamic ticketing firms in the US, has consulted for Derby County and Manchester City football clubs in the UK. “In five years, dynamic pricing will be common practice in the attractions space,” says the company’s CEO, Greg Loewen. “The same goes for many other industries: movies, parking, tour operators.” Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, tweaks countless prices every day. Savvy shoppers have learned to wait for bargains with the help of other sites such as CamelCamelCamel.com, which analyses Amazon price drops and lists the biggest. On a single day on Amazon.co.uk last week, those included a Samsung Galaxy S7 phone, down 14% from £510.29 to £439, and a pack of six 300g jars of Ovaltine, down 33% from £17.94 to £12.

Physical retailers can’t match the agility of their online rivals, not least because changing prices requires altering labels. But “smart shelves” – already common in European supermarkets – are coming to the UK, with digital price displays that allow retailers to offer deals at different times of day, along with information about the products. Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and Tesco have all trialled electronic pricing systems in select stores. Marks & Spencer conducted an electronic pricing experiment last year, selling sandwiches more cheaply during the morning rush hour to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early.

Toby Pickard, senior innovations and trends analyst at the grocery research firm IGD, says this new technology will benefit retailers by enabling them “to gain more data about the products they sell; for example, they can closely gauge how prices fluctuating throughout the day may alter shoppers’ purchasing habits, or if on-shelf digital product reviews increase sales.” IGD’s research suggests there is an appetite for this sort of tech from consumers, too. For example, says Pickard: “Four in 10 shoppers say they are interested in being alerted to offers on their phone while in-store.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest M&S experimented with pricing to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early. Photograph: Luke Johnson/Commissioned for The Guardian

Earlier this year, the Luxembourg-based computer firm SES took a majority stake in the Irish software firm MarketHub. Together, they are bringing data analysis and smart-shelf-style systems to some 14,000 stores in 54 countries including the UK. MarketHub says two Spar stores in London have succeeded in raising revenue and decreasing waste since introducing its technology. For the firm’s CEO Roy Horgan, though, there’s a big difference between what MarketHub offers and dynamic pricing per se. “I don’t see dynamic pricing happening in major retailers,” he says. “Supermarkets have huge, complicated logistics systems. They can’t react in real time to what’s going in their stores the way Amazon can. [Physical retailers] want to discount, to have more relevant deals, fewer promotions, better value and more customer loyalty. That’s not about changing the price of individual products, it’s more about changing deals.”

As examples, Horgan suggests offering cheap lunch deals in the morning (à la M&S), so that workers don’t have to queue up at lunchtime, or guiding shoppers with limited budgets to discounted ingredients for an evening meal. “That’s not dynamic pricing,” he says. “It’s just agile retail.”

A recent survey of US consumers by Retail Systems Research (RSR) found that 71% didn’t care for the idea of dynamic pricing, though millennials were more amenable to the concept, with 14% of younger shoppers saying they “loved” it. Perhaps that ought not to be surprising, given the younger generation’s greater familiarity with browsing for bargains online.

“Consumers always love it when they can get a great deal, and dynamic pricing isn’t just about raising prices – it often leads to lowering them,” says Loewen. “In general, we have found that when prices are transparent to consumers and they understand the ‘rules of the game’, they adapt to dynamic pricing fairly seamlessly and even embrace it.”

Simon Read, a money and personal finance writer, says: “If you’re desperate for an item and it’s the last available, you are likely to pay a premium when dynamic pricing comes into play.” But dynamic pricing can also play to the consumer’s benefit, he explains.

“The truth is that retailers want to flog their wares at whatever price they can get. If you want to take advantage of dynamic pricing, you’ll need to find out when retailers are desperate to sell. In bricks-and-mortar stores that means shopping at quiet times – in the morning – or waiting until closing time when grocers need to clear their shelves.” If you’re shopping online, Read says, research the normal price of an item before buying it, so as not to be caught out. “It’s also a good idea to leave things in your shopping basket at most online retailers rather than buying immediately. After a day or two, you will often get an email offering a decent reduction.”

Those consumers who are suspicious of dynamic pricing may also be confusing it with (the far more controversial) personalised pricing, whereby specific customers are asked to pay different amounts for the same product, tailored to what the retailer thinks they can and will spend – using personal data points that might one day include, for instance, our credit rating. In 2014, the US Department of Transportation approved a system allowing airlines and travel companies to collect passengers’ data to present them with “personalised offerings” based on their address, their marital status, their birthday and their travel history. It’s not hard to imagine that the fares you are offered might be higher than for others if, say, you live in an affluent postcode and your husband’s birthday is coming up.

Airlines use dynamic pricing on flight tickets. Photograph: Easyjet

In 2012, the travel site Orbitz was found to be adjusting its prices for users of Apple Mac computers, after finding that they were prepared to spend up to 30% more on hotel rooms than other customers. That same year, the Wall Street Journal revealed that the Staples website offered products at different pricesdepending on the user’s proximity to rival stores. In 2014, a study conducted by Northeastern University in Boston found that several major e-commerce sites such as Home Depot and Walmart were manipulating prices based on the browsing history of individual customers. “Most people assume the internet is a neutral environment like the high street, where the price you see is the same as the one everyone else sees,” says Ariel Ezrachi, director of the University of Oxford Centre for Competition Law and Policy. “But on the high street you’re anonymous; online, the seller has information about you, and about your other buying options.”

Dynamic pricing, says Ezrachi, is simply a way for businesses to respond nimbly to market trends, and thus is within the bounds of what consumers already accept as market dynamics. “Personalised pricing is much more problematic. It’s based on asymmetricity of information; it’s only possible because the shopper doesn’t know what information the seller has about them, and because the seller is able to create an environment where the shopper believes they are seeing the market price.”

The ethics of pricing based on an individual’s personal data are vexed: some consumers will find it manipulative and insist on its regulation; others may feel it’s fair – socially beneficial, even – to charge wealthy customers more for a product or service. “You will find people arguing in different directions,” Ezrachi says. Loyalty cards have long enabled supermarkets and other major retailers to offer personalised offers based on the spending habits of repeat customers. B&Q has tested electronic price tags that display different prices to different customers using information gleaned from their phones (the company made clear that their intention was to “reward regular customers with discounts”, not to raise the price for more profligate shoppers). In the US, Coca-Cola and Albertsons supermarkets have experimented with targeting shoppers in-store by sending personalised offers to their phones when they approach the soft drinks aisle in an Albertsons store.

Horgan resists the idea that supermarkets will embrace personalised pricing. “In the airline industry, we have more freedom, information and choice on airlines than we’ve ever had before, and that is all dynamic-pricing led. But nobody’s loyal to Ryanair; they’re loyal to the deal. Retail is different,” he says. “If I have five pounds in my pocket and a family of four to feed, I want to know I can generate a recipe that is nutritious for them, and I want an app that can navigate me around the store to find a deal on [the necessary ingredients]. To me, that is personalised retail. But any [bricks and mortar] retailer who charges different prices to different people for the same product is an idiot. They’re only going to lose loyalty.”

Loewen agrees that personalised pricing carries as many dangers as opportunities for retailers. “Consumers are more empowered and informed than ever before, and any pricing strategy that seeks to fool or mislead them is unlikely to be successful for long,” he says. Nevertheless, in the dawning era of dynamic pricing, personalised pricing and agile retailing, the days of fixed prices seem to be coming to an end. And although the technology may be more advanced, in some ways dynamic pricing is simply a return to the days long before supermarkets, when traders would judge how high or low a price to haggle from a customer based on factors as simple as the sound of their accent, or the cut of their cloak.

Saturday, 21 October 2017

British banks can’t be trusted – let’s nationalise them

Owen Jones in The Guardian

Sometimes the case for a policy is as overwhelming as the level of ridicule it will get from the punditocracy. The nationalisation of Britain’s failed banking industry – the sector responsible for most of our country’s current ills – is one such example. According to a recent poll, half the electorate support nationalising the banks, despite almost no one arguing for such a policy in public life.

It may well be because the banks plunged Britain into one of its worst economic crises in modern history, spawning, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, perhaps our worst squeeze in living standards since the 1750s. The fact that they have been bailed out by the taxpayer but allowed to carry on as though little happened – including more top British bankers in 2013 being gifted bonuses worth over €1m than all EU countries combined – while public services are gratuitously slashed, has rightly riled some British voters.

Nationalisation of the banks is not about vengeance, though. Sure, the rip-off inefficiency of rail privatisation, or the failure of the great energy sell-off, or the fact that even the Financial Times has argued that privately run water is an indefensible debacle – all are testament to the intellectual poverty of the “private good, public bad” argument. None quite compete, however, with the matter of the banks leaving the entire western world consumed with the gravest series of crises since the second world war.

Would Brexit, Donald Trump, or the gathering demands for Catalonia to secede from crisis-ridden Spain have happened without the financial collapse? Almost certainly not. It is now somewhat darkly comic to note that most commentators and politicians claimed Labour lost the 2015 election because it was too leftwing. It is notable, then, that over four in 10 voters back then believed Labour was too soft on banks and big business, compared to just over one in five who differed.

Economist Laurie Macfarlane says the banks make a mockery of the nostrums of free-market capitalism. Because the banks were given state bailouts after their catastrophic failures, there is the assumption that, when another crisis hits, the same will happen again.

No other industry enjoys the same protection. They are “too big to fail”, which means they benefit from an implicit subsidy – worth £6bn in 2015. The Bank of England is their lender of last resort. State-backed deposit insurance of up to £85,000 per consumer is another de facto mass public subsidy.

As the New Economics Foundation says, it is commercial banks who are now responsible for creating the vast majority of money in economies like the UK, a source of vast profit. This is called “seigniorage” and – as the foundation puts it – it represents a “hidden annual subsidy” of £23bn a year, or nearly three-quarters of the banks’ after-tax profits. And banks are an essential public utility: it is almost impossible to be a citizen without a bank account, and there is no public option when it comes to making electronic payments.

Even now, as Macfarlane notes, the British state technically owns a fifth of the retail banking industry because of its stake in Royal Bank of Scotland. Repeated RBS scandals, and the aftermath of the EU referendum result, have dented the worth of the company’s shares, meaning that the state selling its stake would result in eye-watering losses. Meanwhile, small businesses have struggled to get the credit they need, and escalating household debt threatens the foundations of the stagnating British economy. But the state’s arms-length approach means RBS has failed both its customers and the broader economy. A profit-driven banking sector closed 1,150 branches in 2014 and 2015; about a third of those were owned by RBS. The bank once promised never to close the last branch in town; the pledge was broken, and 1,500 communities have been left with no bank branch. Vulnerable customers and small businesses inevitably suffer the most.

By contrast, foreign publicly owned banks are self-evident successes. Take Germany: KFW, the government-owned development bank, is crucial in developing national infrastructure as well as the renewable energy revolution. On a regional level, state-owned Landesbanken are responsible for industrial strategy. Then at the most local level, there are Sparkassen: they focus on developing relationships with local businesses and consumers. They’re not beholden to shareholders – instead, they have a stakeholder model, focused on helping local economies – indeed, their capital has to remain in local communities.

It is impossible to understand Britain’s current plight without examining the country’s rapid deindustrialisation in favour of a financial sector concentrated in London and the south-east. And according to New Economics Foundation, while foreign stakeholder banks lend two thirds of their assets to individuals and businesses in the real economy, that’s true with only a tiny proportion of British shareholder banks. Overwhelmingly, it goes to mortgage lending and lending to other financial institutions.