'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label banker. Show all posts

Showing posts with label banker. Show all posts

Sunday, 5 June 2022

Wednesday, 2 June 2021

2 Why central bankers no longer agree how to handle inflation

Chris Giles, James Politi, Martin Arnold and Robin Harding in The FT

Once, central bankers knew what they needed to do to handle inflation. As they grapple with the economic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, the consensus on how best to foster low and stable price growth has broken down.

After years of setting interest rates on the basis of inflation forecasts and seeking to hit a target of about 2 per cent, the leading monetary authorities around the world are pursuing different strategies.

The OECD warned this week that “vigilance is needed”, but any attempt to raise interest rates should be “state-dependent and guided by sustained improvements in labour markets, signs of durable inflation pressures and changes in the fiscal policy stance” — so vague that every major central bank can say its policy meets the criteria.

The US Federal Reserve has shifted its stance to give more leeway to inflation and greater priority to employment, the European Central Bank is embroiled in a row over whether to be more tolerant of any inflation overshoot, and the Bank of Japan is vainly battling to revive consumers’ price growth expectations.

The US shift in strategy has been the most radical; last year Fed chair Jay Powell announced a new monetary framework.

The Fed’s creed seeks to move away from decades of pre-emptive interest rate increases to stave off potential inflationary pressures while more doggedly pursuing full employment, a strategy that it argues will benefit more Americans, including low-wage workers and minority groups.

It will allow inflation to overshoot its 2 per cent target for some time after a prolonged undershoot, in an attempt to ensure companies and businesses expect interest rates to remain low for a long time and will therefore spend rather than save. One of the Fed’s motivations is to avoid repeating its stance after the financial crisis, when policy tightening slowed the recovery.

“I am attentive to the risks on both sides of this expected path,” said Lael Brainard, a Fed governor, on Tuesday. She would “carefully monitor” inflation data to make sure it did not develop in “unwelcome ways” but also “be attentive to the risks of pulling back too soon”, she said, warning that pre-pandemic trends of “low equilibrium interest rates [and] low underlying trend inflation” were “likely to reassert” themselves.

But critics worry the Fed’s strategy was designed for a world of cautious fiscal policy, not the pandemic era of massive borrowing and spending, and that this could leave it behind the curve if price pressures build.

Friday’s 3.1 per cent annual rise in the core personal consumption expenditure index reinforced some of those fears.

The BoJ has been pursuing an inflation-overshoot commitment for the past five years, but has not even got close to its 2 per cent target. Strikingly little has changed after the pandemic: inflation is nowhere on the horizon and spending growth is sluggish.

Japan’s households and companies are convinced inflation will remain near zero, making it all but impossible for the BoJ to achieve its goal.

“The formation of inflation expectations in Japan is deeply affected by not only the observed inflation rate at the time but also past experiences and the norms developed in the process,” BoJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda said in a recent speech.

Meanwhile eurozone policymakers are embroiled in a furious argument as the ECB conducts its own policy review; the results will be announced in September.

Olli Rehn, who sits on the council as governor of Finland’s central bank, recently said: “From the point of view of economic and social welfare it makes sense to accept a certain period of [inflation] overshooting, while taking into account the history of undershooting.”

But Isabel Schnabel, an ECB executive director, warned that would be risky. Schnabel said last month that although the central bank should not overreact if inflation overshoots after sluggishness, she is “sceptical” of formally targeting average inflation over a set period.

“How long should the period be over which the average is calculated? How much of that should be communicated?” she asked. “I personally don’t think we should follow such a strategy.”

For some economists, these disagreements are beside the point: monetary policy has become so extended that central bankers lack effective tools to do more.

Richard Barwell, head of macro research at BNP Paribas Asset Management, said the ECB was almost “out of ammunition” and while eurozone inflation in May rose just above its target of near but below 2 per cent, it would take ambitious fiscal policy or simply luck to do so for a sustained period.

“Unless there is some massive Biden-style fiscal stimulus coming down the road in Europe or the disinflationary headwinds suddenly dissipate, the amount of monetary stimulus needed to get inflation above 2 per cent is . . . well beyond what they can do,” he said.

That leaves the Fed alone with a difficult choice in the months ahead. US inflation is overshooting its target, demand is rampant and it needs to decide whether to apply the brakes gently.

Policymakers are poised to open a debate winding down some support, but they have shown no sign of wavering from their new policy framework, insisting the recent inflation rise is likely to be transitory, not sustained.

Last week Fed vice-chair Randal Quarles said the framework was designed for the current world with “slow workforce growth, lower potential growth, lower underlying inflation and, therefore, lower interest rates”.

“I am not worried about a return to the 1970s,” he said.

Thursday, 4 October 2018

Finance, the media and a catastrophic breakdown in trust

John Authers in The Financial Times

Finance is all about trust. JP Morgan, patriarch of the banking dynasty, told Congress in the 1912 hearings that led to the foundation of the US Federal Reserve, that the first thing in credit was “character, before money or anything else. Money cannot buy it.

Finance is all about trust. JP Morgan, patriarch of the banking dynasty, told Congress in the 1912 hearings that led to the foundation of the US Federal Reserve, that the first thing in credit was “character, before money or anything else. Money cannot buy it.

“A man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom,” he added. “I think that is the fundamental basis of business.” He was right. More than a century later, it is ever clearer that, without trust, finance collapses. That is no less true now, when quadrillions change hands in electronic transactions across the globe, than it was when men such as Morgan dominated markets trading face to face.

And that is a problem. Trust has broken down throughout society. From angry lynch mobs on social media to the fracturing of the western world’s political establishment, this is an accepted fact of life, and it is not merely true of politics. Over the past three decades, trust in markets has evaporated.

In 1990, when I started at the Financial Times, trust in financiers and the media who covered them was, if anything, excessive. Readers were deferential towards the FT and, particularly, the stone-tablet certainties of the Lex column, which since the 1930s has dispensed magisterial and anonymous investment advice in finely chiselled 300-word notes.

Trainee bankers in the City of London were required to read Lex before arriving at the office. If we said it, it must be true. Audience engagement came in handwritten letters, often in green ink. Once, a reader pointed out a minor error and ended: “The FT cannot be wrong, can it?” I phoned him and discovered this was not sarcasm. The FT was and is exclusively produced by human beings, but it had not occurred to him that we were capable of making a mistake.

Back then, we made easy profits publishing page after page of almost illegible share price tables. One colleague had started in the 1960s as “Our Actuary” — his job was to calculate, using a slide rule, the value of the FTSE index after the market closed.

Then came democratisation. As the 1990s progressed, the internet gave data away for free. Anyone with money could participate in the financial world without relying on the old intermediaries. If Americans wanted to shift between funds or countries, new online “ fund supermarkets” sprung up to let them move their pension fund money as much as they liked.

Technology also broke the hold of bankers over finance, replacing it with the invisible hand of capital markets. No longer did banks’ lending officers decide on loans for businesses or mortgages; those decisions instead rested in the markets for mortgage-backed securities, corporate paper and junk bonds. Meanwhile, banks were merged, deregulated and freed to re-form themselves.

But the sense of democratisation did not last. The crises that rent the financial world in twain, from the dotcom bubble in 2000 through to the 2008 Lehman debacle and this decade’s eurozone sovereign debt crisis, ensured instead that trust broke down. That collapse appears to me to be total: in financial institutions, in the markets and, most painfully for me, in the financial media. Once our word was accepted unquestioningly (which was unhealthy); now, information is suspect just because it comes from us, which is possibly even more unhealthy.

To explain this, let me tell the story of the most contentious trip to the bank I have ever made.

Two days after Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, in September 2008, I went on an anxious walk to my local bank branch. Working in New York, I had recently sold my flat in London and a large sum had just landed in my account at Citibank — far more than the insured limit, which at that point was $100,000.

It did not seem very safe there. Overnight, the Federal Reserve had spent $85bn to bail out the huge insurance company AIG, which had unwisely guaranteed much credit now sitting on banks’ books. Were AIG to go south, taking its guarantees with it, many banks would suddenly find themselves with worthless assets and become insolvent.

Meanwhile, a money market fund had “broken the buck”. Money market funds were treated like bank accounts by their clients. They switch money between very safe short-term bonds, trying to find higher rates than a deposit account can offer. Each share in the fund is worth $1, interest is distributed and the price cannot dip below $1. As the funds did not pay premiums for deposit insurance, they could pay higher interest rates for no perceived extra risk.

Thus there was outright panic when a large money market fund admitted that it held Lehman Brothers bonds, that its price must drop to 97 cents and that it was freezing access to the fund. Across the US, investors rushed to pull their money out of almost anything with any risk attached to it, and poured it into the safest investments they could find — gold and very short-term US government debt (Treasury bills, or T-bills). This was an old-fashioned bank run, but happening where the general public could not see it. Panic was only visible to those who understood the arcana of T-bill yields.

Our headline that day read “Panic grips credit markets” under a banner about the “banking crisis” in red letters.

There was no time to do anything complicated with my own money. Once I reached my lunch hour, I went to our local Citi branch, with a plan to take out half my money and put it into rival bank Chase, whose branch was next door. This would double the amount of money that was insured.

This is how I recounted what happened next, in a column for the FT last month:

“We were in Midtown Manhattan, surrounded by investment banking offices. At Citi, I found a long queue, all well-dressed Wall Streeters. They were doing the same as me. Next door, Chase was also full of anxious-looking bankers. Once I reached the relationship officer, who was great, she told me that she and her opposite number at Chase had agreed a plan of action. I need not open an account at another bank. Using bullet points, she asked if I was married and had children. Then she opened accounts for each of my children in trust and a joint account with my wife. In just a few minutes I had quadrupled my deposit insurance coverage. I was now exposed to Uncle Sam, not Citi. With a smile, she told me she had been doing this all morning. Neither she nor her friend at Chase had ever had requests to do this until that week.”

Ten years on, this is my most vivid memory of the crisis. The implications were clear: Wall Streeters, who understood what was going on, felt they had to shore up their money in insured deposits. The bank run in the trading rooms was becoming visible in the bank branches down below.

In normal circumstances, the tale of the bank branch would have made an ideal anecdote with which to lead our coverage, perhaps with a photo of the queue of anxious bankers. Low T-bill yields sound dry and lack visual appeal; what I had just seen looked like a bank run. (Although technically it was not — nobody I saw was taking out money.)

But these were not normal circumstances, and I never seriously considered writing about it. Banks are fragile constructs. By design, they have more money lent out than they keep to cover deposits. A self-fulfilling loss of confidence can force a bank out of business, even if it is perfectly well run. In a febrile environment, I thought an image of a Manhattan bank run would be alarmist. I wrote a piece invoking a breakdown in trust between banks and described the atmosphere as “panic”, but did not mention the bank branch. Ten years later, with the anniversary upon us, I thought it would be an interesting anecdote to dramatise the crisis.

In the distrustful and embittered world of 2018, the column about what I saw and why I chose not to write about it provoked a backlash that amazed me. Hundreds of responses poured in. Opinion was overwhelmingly against me.

One email told me: “Your decision to save yourself while neglecting your readership is unforgivable and in the very nature of the elitist Cal Hockley of the Titanic scrambling for a lifeboat at the expense of others in need.” One commenter on FT.com wrote: “This reads like Ford trying to explain why pardoning Nixon was the right thing to do.”

“I have re-read the article, and the comments, a couple of times,” wrote another. “And I realised that it actually makes me want to vomit, as I realise what a divide there is between you and I, between the people of the establishment like yourself, and the ordinary schmucks like myself. The current system is literally sickening and was saved for those who have something to protect, at the expense of those who they are exploiting.”

Feedback carried on and on in this vein. How could we in the media ever be trusted if we did not tell the whole truth? Who were we to edit the facts and the truth that were presented? Why were we covering up for our friends in the banks? Newspaper columns attacking me for my hypocrisy popped up across the world, from France to Singapore.

I found the feedback astonishing and wrong-headed. But I am now beginning to grasp the threads of the problem. Most important is the death of belief in the media as an institution that edits and clarifies or chooses priorities. Newspapers had to do this. There was only so much space in the paper each day. Editing was their greatest service to society.

Much the same was true of nightly half-hour news broadcasts in pre-cable television. But now, the notion of self-censorship is alien and suspect. People expect “the whole truth”. The idea of news organisations with long-standing cultures and staffed by trained professionals deciding what is best to publish appears bankrupt. We are not trusted to do this, and not just because of politicians crying “fake news”.

Rather, the rise of social media has redefined all other media. If the incident in the Citi branch were to happen today, someone would put a photo of it on Facebook and Twitter. It might or might not go viral. But it would be out there, without context or explanation. The journalistic duty I felt to be responsible and not foment panic is now at an end. This is dangerous.

Another issue is distrust of bankers. Nobody ever much liked “fat cats”, but this pickled into hatred as bankers avoided personal criminal punishment for their roles in the crisis. Bank bailouts were, I still think, necessary to protect depositors. But they are now largely perceived merely as protecting bankers. My self-censorship seemed to be an effort to help my friends the bankers, not to shield depositors from a panic.

Then there is inequality. In my column, I said that I “happened to have a lot of money in my account” but made no mention of selling my London flat. People assumed that if I had several hundred thousand dollars sitting in a bank account, I must be very rich. That, in many eyes, made my actions immoral. Once I entered the FT website comments thread to explain where the money had come from, some thought this changed everything. It was “important information”. “In the article where moral questions [were] raised, the nature of the capital should have been explained better,” one commenter said.

The hidden premise was that if I were rich, I would not have been morally entitled to protect my money ahead of others lacking the information I was privy to. Bear in mind that to read this piece, it was necessary to subscribe to the FT.

Put these factors together, and you have a catastrophic breakdown in trust. How did we get here?

The democratisation of finance in the 1990s was healthy. Transparency revealed excessive fees that slowly began to fall. For us at the FT, in many ways an entrenched monopoly, this meant lost advertising and new competition from cable TV, data providers and an array of online services.

But that democratisation was tragically mishandled and regulators let go of the reins far too easily. In 1999, as the Nasdaq index shot to the sky, the share prices of new online financial media groups such as thestreet.com shot up with them. On US television, ads for online brokers showed fictional truck drivers apparently buying their own island with the proceeds of their earnings from trading on the internet. By 2000, when I spent time at business school, MBA students day-traded on their laptops in class, oblivious to what their professors were saying.

Once that bubble burst, the pitfalls of rushed democratisation were painfully revealed. Small savers had been sucked into the bubble at the top, and sustained bad losses.

Trust then died with the credit crisis of 2008 and its aftermath. The sheer injustice of the ensuing government cuts and mass layoffs, which deepened inequality and left many behind while leaving perpetrators unpunished, ensured this.

The public also lost their trust in journalists as their guides in dealing with this. We were held to have failed to warn the public of the impending crisis in 2008. I think this is unfair; the FT and many other outlets were loudly sceptical and had been giving the problems of US subprime lenders blanket coverage for two years before Lehman Brothers went down. In the earlier dotcom bubble, however, I think the media has more of a case to answer — that boom was lucrative for us and many were too credulous, helping the bubble to inflate.

Further, new media robbed journalists of our mystique. In 1990, readers had no idea what we looked like. Much of the FT, including all its stock market coverage, was written anonymously. The only venue for our work was on paper and the only way to respond (apart from the very motivated, who used the telephone) was also on paper. The rule of thumb was that for every letter we received, at least another hundred readers felt the same way.

Now, almost everything in the paper that expresses an opinion carries a photo. Once my photo appeared above my name on the old Short View column, my feedback multiplied maybe fivefold. The buzzword was to be “multimodal”, regaling readers with the same ideas in multiple formats. In 2007 we started producing video.

My readers became my viewers, watching me speak to them on screen every day, and my feedback jumped again. Answering emails from readers took over my mornings. Often these would start “Dear John”, or even just “John”, as though from people who knew me. So much for our old mystique.

By 2010, social media was a fact of life. Writing on Twitter, journalists’ social network of choice, became part of the job. People expected us to interact with them. This sounds good. We were transparent and interactive in a way we had not been before. But it became part of my job to get into arguments with strangers, who stayed anonymous, in a 140-character medium that made the expression of any nuance impossible.

Meanwhile, the FT hosted social media of its own. Audience engagement became a buzzword. If readers commented, we talked back. Starting in 2012, I started debating with readers and I learnt a lot. FT readers are often specialists, and they helped me understand some arcane subject matter. Once, an intense discussion with well over a hundred entries on the subject of cyclically adjusted price/earnings multiples (don’t ask) yielded all the research I needed to write a long feature.

Now, following Twitter, comments below the line are degenerating into a cesspit of anger and disinformation. Where once I debated with specialists, now I referee nasty political arguments or take the abuse myself. The status of the FT and its competitors in the financial media as institutions entrusted with the task of giving people a sound version of the truth now appears, to many, to be totally out of date.

Even more dangerously for the future, the markets and their implicit judgments have been brought into the realm of politics (and not just by President Trump). This was not true even 20 years ago; when Al Gore faced off against George W Bush in 2000, only months after the dotcom bubble burst, neither candidate made much of an issue of it.

But now, following Lehman, people understand that decisions made in capital markets matter. That makes markets part of the political battlefield; not just how to interpret them, but even the actual market numbers are now open to question.

Brexit rammed this home to me. During the 2016 referendum campaign, Remainers argued that voting to leave would mean a disastrous hit for sterling. This was not exactly Project Fear; whether or not you thought Brexit was a good idea, it was obvious that it would initially weaken the pound. A weaker currency can be good news — the pound’s humiliating exit from the EU’s exchange rate mechanism in 1992, for example, set the scene for an economic boom throughout the late 1990s.

But reporting on the pound on the night of the referendum was a new and different experience. Sitting in New York as the results came in through the British night, I had to write comments and make videos, while trying to master my emotions about the huge decision that my home country had just taken. Sterling fell more than 10 per cent against the dollar in a matter of minutes — more than double its previous greatest fall in the many decades that it had been allowed to float, bringing it to its lowest level in more than three decades. Remarkably, that reaction by foreign exchange traders has stood up; after two more years of political drama, the pound has wavered but more than two years later remains slightly below the level at which it settled on referendum night.

As I left, at 1am in New York, with London waking up for the new day, I tweeted a chart of daily moves in sterling since 1970, showing that the night’s fall dwarfed anything previously seen. It went viral, which was not surprising. But the nature of the response was amazing. It was a factual chart with a neutral accompanying message. It was treated as a dubious claim.

“LOL got that wrong didn’t you . . . oops!” (There was nothing wrong with it.) “Pretty sure it was like that last month. Scaremongering again.” (No, it was a statement of fact and nothing like this had happened ever, let alone the previous month.)

“Scaremongering. Project Fear talking us down. This is nothing to do with Brexit, it’s to do with the PM cowardice resignation.” (I had made the tweet a matter of hours before David Cameron resigned.)

The reaction showed a willingness to doubt empirical facts. Many also felt that the markets themselves were being political and not just trying to put money where it would make the greatest return. “Bankers punish Britons for their audacity in believing they should have political control of their own country.” (Forex traders in the US and Asia were probably not thinking about this.)

“It will recover, this is what uncertainty does. Also the rich bitter people upset about Brexit.” (Rich and bitter people were unlikely to make trades that they thought would make them poorer, and most of that night’s trading was by foreigners more dispassionate than Britons could be at that point.)

So it continued for days. Thanks to the sell-off in sterling, the UK stock market did not perform that badly (unless you compared it with others, which showed that its performance was lousy). Whether the market really disliked the Brexit vote became a topic of hot debate, which it has remained — even as the market verdict, that Brexit is very bad news if not a disaster, becomes ever clearer.

After Brexit, of course, came Trump. The US president takes the stock market as a gauge of his performance, and any upward move as a political endorsement — while his followers treat any fall, or any prediction of a fall by pundits such as me, as a political attack. The decade in which central banks have bought assets in an open attempt to move markets plays into the narrative that markets are political creations.

This is the toxic loss of trust that now vitiates finance. Once lost, trust is very hard to retrieve, which is alarming. It is also not clear what the financial media can do about it, beyond redoubling our efforts to do a good job.

All the most obvious policy responses come with dangers. Regulating social media from its current sick and ugly state would have advantages but would also be the thin end of a very long wedge. Greater transparency and political oversight for central banks might rebuild confidence but at the risk of politicising institutions we desperately need to maintain independence from politicians. And an overhaul of the prosecutorial system for white-collar crime, to avert the scandalous way so many miscreants escaped a reckoning a decade ago, might work wonders for bolstering public trust — but not if it led to scapegoating or show trials.

On one thing, I remain gloomily clear. Without trust in financial institutions themselves, or those who work in them, or the media who cover them, the next crisis could be far more deadly than the last. Just ask JP Morgan.

Wednesday, 4 July 2018

It is a mystery why bankers earn so much

John Gapper in The FT

In the libel suit he brought in 1878 against John Ruskin, the Victorian painter James McNeill Whistler was asked under cross-examination how he justified charging 200 guineas for a painting of a London firework display that took him two days to finish. “I ask it for the knowledge of a lifetime,” Whistler declared.

In the libel suit he brought in 1878 against John Ruskin, the Victorian painter James McNeill Whistler was asked under cross-examination how he justified charging 200 guineas for a painting of a London firework display that took him two days to finish. “I ask it for the knowledge of a lifetime,” Whistler declared.

Investment bankers explain their bonuses in the same manner, although the rewards for mergers and acquisitions advisers are rather greater than for most painters. Goldman Sachs will be paid $58m by 21st Century Fox for its advice on Fox’s planned $71bn asset sale to Walt Disney (and the bank stands to gain another $47m for financing the remainder of Fox).

They are remarkable paydays — today’s dealmaking boom is the most rewarding time in history to be a global M&A banker. It is especially lucrative for those in the top league of advisers who run many auctions. An individual with the ability to shepherd nervous boards of directors past the pitfalls and a reputation for squeezing the best prices can name his or her fee.

But what exactly do they do for the money? When asked this question, they turn sheepish and talk vaguely about the art of persuasion rather than the science of valuation. The secret to a bulging “success fee” is less to obtain the best possible deal than to make the chief executive and the board believe they got it. That is not the same thing, particularly in the long term.

The M&A adviser’s job has three qualities that put its practitioners in a powerful bargaining position over their own pay. First, the stakes are very high. One former banker compares it to a surgeon explaining his or her charges as a patient is being wheeled into the operating theatre. The latter needs to have the best possible professional and is in no position to quibble.

Going through an M&A auction can feel like being operated upon for directors who have not experienced it before. Shareholders and the media lurk, ready to condemn any slip-up (the latter risk is why public relations consultants get paid so much as well). There is plenty of subterfuge and bargaining over details, any of which could unexpectedly prove fatal to the outcome.

Second, advisers are paid with other people’s money. That is especially true when a company is being sold — the overall price including the fees is going to be picked up by the acquirer, so what difference does a few million make? Even when the client is an acquirer, boards of directors whose personal reputations are at stake are not digging into their own pockets to pay.

Through one end of the telescope, the fees even look small. The average fee for selling a company worth between $10bn and $25bn is about 0.3 per cent, and can cover years of unpaid work. Bankers claim they are cheap compared with property brokers, who may charge several percentage points for selling a house. As ever, the best way to make money is to be around a lot of it.

Third, M&A advice is a black box. There is plenty of technical skill in structuring a transaction such as using acquisitions to change tax domiciles. That is bundled with access to the bank’s contacts with potential bidders in various countries and presented as a whole by one adviser to the board. The senior banker’s tone of voice conveys a mixture of financial advice, human judgment and comfort.

The last is the most valuable. In theory, M&A advice could be unbundled into different tasks, and more of the technical work done by machines, but boardrooms only have space for a few people. They are crowded enough by companies’ baffling habit of hiring several banks to advise on big deals and paying them $20m each, which one adviser calls “ludicrous”.

The fee rises exponentially for an adviser in the room where a deal happens. This accounts for the prosperity of advisory boutiques such as Centerview Partners and Evercore, founded by corporate financiers who built their reputations at banks including UBS and Lehman Brothers. The power of a global advisory elite is exemplified by tiny and highly rewarded banking “kiosks” such as Robey Warshaw.

Global investment banks sniff at the ability of a few experienced individuals to charge similar fees to them, without bearing the same costs. “The boutiques are full of guys cashing in at the end of their careers and they get a bit of a free ride,” says one adviser at a big bank. In the M&A business, relationships have enduring value.

But hiring the best cosmetic surgeon in the world does not make cosmetic surgery a good idea. Deals can be brilliantly executed at the time without adding to a company’s long-term value and many are unwound — often with the help of the same advisers — when a chief executive leaves. “Companies pay far too much to advisers. It’s really not worth it,” says Peter Zink Secher, co-author of The M&A Formula.

The success fees of advisers should be more closely tied to whether the deal succeeds long after it has closed and they have moved on to the next one. Whistler won his libel suit against Ruskin for having accused him of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”, but was only awarded damages of a farthing. Even artists can push their luck.

Friday, 17 February 2017

Friday, 1 April 2016

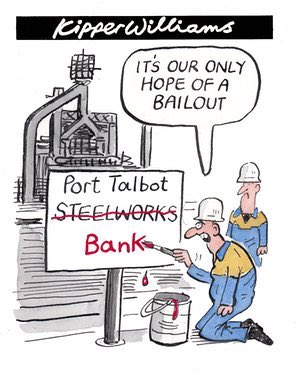

"You Don't Deserve a Bailout - You are NEITHER a Banker NOR Chinese"

If librarians and steelworkers wanted state bail-outs, they should have done something

useful - like bankers

In any case the bankers deserved to be bailed out, as they couldn’t possibly anticipate that if they kept taking money it might eventually run out, whereas steelworkers have caused their own downfall by not being Chinese.

Mark Steel in The Independent

The main thing to realise with the current steel industry crisis is that the government has been clear and decisive. They’ve stated firmly, “We’re not ruling out anything at all, though we are ruling out nationalising anything as that doesn’t count as anything, but we will do anything we possibly can that won’t make a difference such as drawing a pretty picture of a caterpillar, and we’re doing all we can because as we keep saying there’s nothing we can do, but we do feel desperately sorry for anyone who loses their job which is why any steelworkers who become redundant will immediately be called in to the job centre for an interview and told they won’t get any benefits if their answer to ‘Why have you let yourself be put of work?’ is ‘There was nothing I could do’.”

---Also read

------

Some people have pointed out that other industries were bailed out by governments in the past - but this has only been if they’ve produced essential goods, such as hedge funds and executive bonuses, not frivolities like the stuff that makes ships and teaspoons.

In any case the bankers deserved to be bailed out, as they couldn’t possibly anticipate that if they kept taking money it might eventually run out, whereas steelworkers have caused their own downfall by not being Chinese.

Luckily this sound economics is understood across the country, including by the sensible wing of the Labour Party such as those in charge of Lambeth Council, who are closing half the borough’s libraries and turning them into gyms.

This is the sort of can-do attitude people want from Labour. Hopefully it will spark off other schemes, such as turning social services departments into sushi bars, or converting disabled people’s wheelchairs into drones so they can be rented out to the RAF.

There’s no point in complaining about this; it’s the way the free market works. And if the Chinese are flooding South London with cheap Agatha Christies, we just have to accept it, and ask the elderly people who rely on going to libraries as their only point of contact with the community to spend all morning performing 200 reps of 40 kilograms per calf on a multi-gym body-solid squat machine instead.

One of these libraries, the Tate, has been assessed as receiving an average of 600 visits per day. This may seem successful, but where the library has let itself down is forgetting to charge any of them money for borrowing books and bringing kids into reading classes.

Maybe the library service should learn from gyms, and only let them in if they pay £40 a month on a minimum two-year contract. They could even offer them special courses in which an instructor screams, “Right, everyone, let’s all read this week’s Economist - you CAN do it - let’s drive ourselves to the limit - GO – ‘the Yen faces unexpected slow down’ - come on Eileen pick it up, PUSH everyone!”

The council insists they will preserve the essence of the libraries, because each of the gyms will include a “lounge with a limited supply of books”. Obviously they won’t have all those unnecessary books you see in old-fashioned libraries, but surely no one’s so fussy they insist on any specific book, as most books are pretty much the same.

The council also agreed that “under-18s may not be allowed in these lounges”, which will surely improve the service as rooms with books aren’t a suitable environment for the young.

Surprisingly, the local population appears shamefully ignorant about economics - so there have been daily protests against the closures, in which thousands have taken part. It seems these people don’t understand that it may have been all right to build and maintain free libraries back in the 1930s, but you can’t expect us to keep funding the luxuries we could afford back then.

So the council demanded a banner was taken down at one library, which was changed each day to tell people how many days were left until it was closed. Maybe the council hoped that if people weren’t reminded of the closure, they just wouldn’t notice. Then eventually they’d all tell stories of success and improvement to each other, such as: “I asked for a reference book on growing cucumbers and was sent into the corner. After three weeks I didn’t feel I was making any progress with my gardening, but then someone told me I’d spent the whole time benching 140 kilograms and now I’m the all-Hertfordshire Over-60s Bodybuilding champion.”

Nevertheless, the protests continue. But the libraries have probably been lending the wrong assets if they want state intervention. Instead of irresponsibly lending books to people who live round the corner so they can read and study and educate and entertain themselves and their kids, they should have lent billions of dollars to anyone who asked for it, without even suggesting a 40p fine if they kept it a week too long.

Then, once they’d succeeded in ruining the world economy, they’d have had a very reasonable case for being bailed out - unlike these people who want to fund steelworks and libraries because they don’t understand the world economy.

------- The China Tariff matter

The Guardian on 1/04/2014

China has risked raising tensions over its role in the UK steel crisis by imposing a 46% import duty on a type of high-tech steel made by Tata in Wales.

The Chinese government said it had slapped the tariff on “grain-oriented electrical steel” imported from the European Union, South Korea and Japan. It justified the move by saying imports from abroad were causing substantial damage to its domestic steel industry.

Tata Steel, whose subsidiary Cogent Power makes the hi-tech steel targeted by the levy in Newport, south Wales, was unable to say on Friday whether any Cogent products are exported to China.

News of the tariff emerged as David Cameron confronted the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, on the sidelines of a summit dinner in Washington on Thursday night, urging him to use Beijing’s presidency of the G20 group of leading countries to tackle the problem.

Asked if Cameron raised concerns about British job losses from Chinese steel dumping, a senior government source said: “He highlighted his concerns, yes.” The source added: “He made clear the concerns that we have on the impact this is having on the UK and other countries.”

British politicians have been accused of pandering to China by blocking new tariffs on Chinese imports to the EU, a measure designed to prop up Europe’s struggling steel industry.

The tariff move by the People’s Republic is likely to anger steelworkers and unions, who blame China for much of the industry’s recent troubles. Steel firms say one of the key reasons for the UK industry’s woes is that state-subsidised firms in China are “dumping” their product on the European market, due to flagging demand at home.

The UK business secretary, Sajid Javid, who visited Tata Steel’s struggling Port Talbot plant on Friday, has been accused of blocking measures to crack down on Chinese imports. Javid voted against EU plans to lift the “lesser duty” rule, which would have allowed for higher duties to be levied on Chinese steel imports. The UK has also lobbied for China to be granted “market economy status”, which would make it even harder to crack down on steel dumping.

“The fact is that the UK has been blocking this,” European Steel Association (Eurofer) spokesperson Charles de Lusignan told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. “They are not the only member state but they are certainly the ring leader in blocking the lifting of the lesser duty rule. The ability to lift this was part of a proposal that the European commission launched in 2013, and the fact that the UK continues to block it means that when the government says it’s doing everything it can to save the steel industry in the UK and also in Europe, it’s not. It’s not true.”

The main thing to realise with the current steel industry crisis is that the government has been clear and decisive. They’ve stated firmly, “We’re not ruling out anything at all, though we are ruling out nationalising anything as that doesn’t count as anything, but we will do anything we possibly can that won’t make a difference such as drawing a pretty picture of a caterpillar, and we’re doing all we can because as we keep saying there’s nothing we can do, but we do feel desperately sorry for anyone who loses their job which is why any steelworkers who become redundant will immediately be called in to the job centre for an interview and told they won’t get any benefits if their answer to ‘Why have you let yourself be put of work?’ is ‘There was nothing I could do’.”

---Also read

Steel v banks: Why they're different when it comes to a government bail-out

------

Some people have pointed out that other industries were bailed out by governments in the past - but this has only been if they’ve produced essential goods, such as hedge funds and executive bonuses, not frivolities like the stuff that makes ships and teaspoons.

In any case the bankers deserved to be bailed out, as they couldn’t possibly anticipate that if they kept taking money it might eventually run out, whereas steelworkers have caused their own downfall by not being Chinese.

Luckily this sound economics is understood across the country, including by the sensible wing of the Labour Party such as those in charge of Lambeth Council, who are closing half the borough’s libraries and turning them into gyms.

This is the sort of can-do attitude people want from Labour. Hopefully it will spark off other schemes, such as turning social services departments into sushi bars, or converting disabled people’s wheelchairs into drones so they can be rented out to the RAF.

There’s no point in complaining about this; it’s the way the free market works. And if the Chinese are flooding South London with cheap Agatha Christies, we just have to accept it, and ask the elderly people who rely on going to libraries as their only point of contact with the community to spend all morning performing 200 reps of 40 kilograms per calf on a multi-gym body-solid squat machine instead.

One of these libraries, the Tate, has been assessed as receiving an average of 600 visits per day. This may seem successful, but where the library has let itself down is forgetting to charge any of them money for borrowing books and bringing kids into reading classes.

Maybe the library service should learn from gyms, and only let them in if they pay £40 a month on a minimum two-year contract. They could even offer them special courses in which an instructor screams, “Right, everyone, let’s all read this week’s Economist - you CAN do it - let’s drive ourselves to the limit - GO – ‘the Yen faces unexpected slow down’ - come on Eileen pick it up, PUSH everyone!”

The council insists they will preserve the essence of the libraries, because each of the gyms will include a “lounge with a limited supply of books”. Obviously they won’t have all those unnecessary books you see in old-fashioned libraries, but surely no one’s so fussy they insist on any specific book, as most books are pretty much the same.

The council also agreed that “under-18s may not be allowed in these lounges”, which will surely improve the service as rooms with books aren’t a suitable environment for the young.

Surprisingly, the local population appears shamefully ignorant about economics - so there have been daily protests against the closures, in which thousands have taken part. It seems these people don’t understand that it may have been all right to build and maintain free libraries back in the 1930s, but you can’t expect us to keep funding the luxuries we could afford back then.

So the council demanded a banner was taken down at one library, which was changed each day to tell people how many days were left until it was closed. Maybe the council hoped that if people weren’t reminded of the closure, they just wouldn’t notice. Then eventually they’d all tell stories of success and improvement to each other, such as: “I asked for a reference book on growing cucumbers and was sent into the corner. After three weeks I didn’t feel I was making any progress with my gardening, but then someone told me I’d spent the whole time benching 140 kilograms and now I’m the all-Hertfordshire Over-60s Bodybuilding champion.”

Nevertheless, the protests continue. But the libraries have probably been lending the wrong assets if they want state intervention. Instead of irresponsibly lending books to people who live round the corner so they can read and study and educate and entertain themselves and their kids, they should have lent billions of dollars to anyone who asked for it, without even suggesting a 40p fine if they kept it a week too long.

Then, once they’d succeeded in ruining the world economy, they’d have had a very reasonable case for being bailed out - unlike these people who want to fund steelworks and libraries because they don’t understand the world economy.

@@@@@@

------- The China Tariff matter

Steel tariff row explained

Here’s a Q&A on the steel tariffs row, from Kate Ferguson of the Press Association.

Q: What is a tariff?

A tariff is a form of tax imposed on goods or services imported from abroad. It can restrict trade by making products more expensive, and can be used as a form of protectionism - to protect and encourage domestic industry.Many in the UK steel industry have demanded higher tariffs be imposed on imported steel amid concerns Chinese steel dumping has sent prices plummeting.

Q: What is steel dumping and why are the Chinese accused of it?

Steel production in China has soared over the past decade and it now produces around half of the world’s annual output of 1.6 billion tonnes. But its domestic market has been slowing, leading steel producers to seek to export more.China has been accused of “dumping” its steel on European markets - which means selling it not just cheaply, but at a loss. In 2014, Chinese steel imports to the UK cost €583 a tonne compared to €897 a tonne for steel produced elsewhere in the EU, according to reports quoting the EU’s statistics agency, Eurostat.

Q: Why has the British Government been criticised for not doing enough to protect the UK steel industry?

Sharply falling prices and a flood of cheap, foreign steel has sparked major concern for the future of the British steel industry, and the many jobs that depend on it.British ministers blocked proposals in the EU to get rid of the “lesser duty rule” which caps tariffs at 9% - in the US some products face a tariff of up to 236%. The British Government has said the 9% tariff is too low, but warned against lurching towards protectionism.The debate comes as Britain has been courting China hard in a bid to foster closer trade links. Chancellor George Osborne said the two nations should “stick together and create a golden decade” while on a visit to China last September.The following month, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Britain and was treated to a State banquet at Buckingham Palace, where he sat between the Queen and the Duchess of Cambridge.Set in this context, the Government has been accused of betraying British steelworkers to curry favour with the Chinese.

The Guardian on 1/04/2014

China has risked raising tensions over its role in the UK steel crisis by imposing a 46% import duty on a type of high-tech steel made by Tata in Wales.

The Chinese government said it had slapped the tariff on “grain-oriented electrical steel” imported from the European Union, South Korea and Japan. It justified the move by saying imports from abroad were causing substantial damage to its domestic steel industry.

Tata Steel, whose subsidiary Cogent Power makes the hi-tech steel targeted by the levy in Newport, south Wales, was unable to say on Friday whether any Cogent products are exported to China.

News of the tariff emerged as David Cameron confronted the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, on the sidelines of a summit dinner in Washington on Thursday night, urging him to use Beijing’s presidency of the G20 group of leading countries to tackle the problem.

Asked if Cameron raised concerns about British job losses from Chinese steel dumping, a senior government source said: “He highlighted his concerns, yes.” The source added: “He made clear the concerns that we have on the impact this is having on the UK and other countries.”

British politicians have been accused of pandering to China by blocking new tariffs on Chinese imports to the EU, a measure designed to prop up Europe’s struggling steel industry.

The tariff move by the People’s Republic is likely to anger steelworkers and unions, who blame China for much of the industry’s recent troubles. Steel firms say one of the key reasons for the UK industry’s woes is that state-subsidised firms in China are “dumping” their product on the European market, due to flagging demand at home.

The UK business secretary, Sajid Javid, who visited Tata Steel’s struggling Port Talbot plant on Friday, has been accused of blocking measures to crack down on Chinese imports. Javid voted against EU plans to lift the “lesser duty” rule, which would have allowed for higher duties to be levied on Chinese steel imports. The UK has also lobbied for China to be granted “market economy status”, which would make it even harder to crack down on steel dumping.

“The fact is that the UK has been blocking this,” European Steel Association (Eurofer) spokesperson Charles de Lusignan told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. “They are not the only member state but they are certainly the ring leader in blocking the lifting of the lesser duty rule. The ability to lift this was part of a proposal that the European commission launched in 2013, and the fact that the UK continues to block it means that when the government says it’s doing everything it can to save the steel industry in the UK and also in Europe, it’s not. It’s not true.”

Wednesday, 28 October 2015

Why don’t we save our steelworkers, when we’ve spent billions on bankers?

Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

‘Britain is entering the early stages of yet another industrial catastrophe.’ Illustration by Andrzej Krauze

Every so often a society decides which of its citizens really matter. Which ones get the star treatment and the big cash handouts – and which get shoved to the bottom of the pile and penalised. These are the big, rough choices post-crash Britain is making right now.

A new hierarchy is being set in place by David Cameron in budget after austerity budget. Wealthy pensioners: winners. Young would-be homeowners: losers. Millionaires see their taxes cut to 45%, while the working poor pay a marginal tax rate of 80%. Big business gets to write its own tax code; benefit claimants face harsh sanctions.

When the contours of this new social order are easy to spot, they can cause public uproar – as with the cuts to tax credits. Elsewhere, they’re harder to pick out, though still central. It is into this category that the crisis in the British steel industry falls.

Every so often a society decides which of its citizens really matter. Which ones get the star treatment and the big cash handouts – and which get shoved to the bottom of the pile and penalised. These are the big, rough choices post-crash Britain is making right now.

A new hierarchy is being set in place by David Cameron in budget after austerity budget. Wealthy pensioners: winners. Young would-be homeowners: losers. Millionaires see their taxes cut to 45%, while the working poor pay a marginal tax rate of 80%. Big business gets to write its own tax code; benefit claimants face harsh sanctions.

When the contours of this new social order are easy to spot, they can cause public uproar – as with the cuts to tax credits. Elsewhere, they’re harder to pick out, though still central. It is into this category that the crisis in the British steel industry falls.

Tata Steel confirms 1,200 job losses as industry crisis deepens

It would be easy to tune out the past few weeks’ headlines about plant closures and job losses as just another story of business disaster. But what’s happening to our steelworkers, and what we do to protect them, goes to the heart of the debate about which people – and which places – count in Britain’s political economy.

If Westminster lets the UK’s steel industry die, it’s in effect declaring that certain regions and the people who live and work in them are surplus to requirements. That it really doesn’t matter if Britain makes things. That the phrase “skilled working-class jobs” is now little more than an oxymoron. That’s the criteria against which to judge MPs, as they continue to take evidence today on the crisis and then debate options.

What does this crisis look like? Imagine coming to work on a September morning – only to find that you and one in six other employees in your entire industry face redundancy before Christmas. That’s the prospect facing British steelworkers. Motherwell, Middlesbrough, Scunthorpe: some of the most kicked-about places in de-industrialised Britain now face more punishment.

Mothball the SSI plant in Redcar and it’s not just 2,200 workers that you send to the dole office and whose families you shove on the breadline. An entire local economy goes on life support: the suppliers of parts, the outside engineers who used to do the servicing, the port workers and hauliers, the cafes and shops. Within days of SSI’s closure, one of Teesside’s biggest employment agencies went into liquidation.

‘If Westminster lets the UK’s steel industry die, it’s effectively declaring that certain regions and the people who live and work in them are surplus to requirements.’ Photograph: Nigel Roddis/Reuters

Steel is a fundamental part of manufacturing, so that the closure of a handful of steelworks in Scotland and the north endangers businesses in Derby and Walsall. At the West Midlands Economic Forum, the chief economist Paul Forrest calculates that about 260,000 jobs in the Midlands rely on steel for everything from basic metals to car assembly and aerospace engineering. He believes that the closures at Tata, SSI and Caparo leave 52,000 local manufacturing workers at direct risk of losing their jobs within the next five years. That’s just after the past few weeks – the UK Steel director Gareth Stace thinks that more plants face closure “within months”.

Join up these predictions, and Britain is entering the early stages of yet another industrial catastrophe. It could finally sink a sector, steel, that actually helps reduce the country’s gaping trade deficit. With that will go another pocket of well-paid blue-collar jobs. Chuck in employer contributions to pensions and national insurance, and the total remuneration per SSI staffer is £40,000 a year. Just try getting such pay in a call centre or distribution warehouse, even as a manager.

Imagine what would happen if manufacturing were centred around the capital, and its executives had Downing Street on speed dial. Actually, you needn’t imagine – merely remember the meltdown of 2008. Then Gordon Brown was so desperate to save the City that the IMF estimates he propped it up with £1.2 trillion of public money. That’s the equivalent of nearly £20,000 from every man, woman and child in the country doled out to bankers in direct cash, loans and taxpayer guarantees.

That’s what the state can do when it decides a sector matters. In 2011 David Cameron stormed out of a Brussels summit rather than agree to more regulation on the City. When it comes to steel, his ministers shrug at the difficulties posed by the EU’s state-aid rules. Michael Heseltine even declares this a “good time” for Teesside’s workers to lose their jobs in Britain’s “exciting” labour market. Let them eat benefits!

True, the problems in the steel industry aren’t confined to these shores. They’re driven by a world economy coming off the boil and China dumping its excess steel output on the global market. Yet other European governments are being far more aggressive in confronting them. Italy’s prime minister, Matteo Renzi, bailed out a huge steelworks last December. Germany’s Angela Merkel ensures that steel producers are cushioned from higher energy prices.

Just how lame, by comparison, is Cameron? Here’s an example: the European commission runs a publicly funded globalisation adjustment fund that can grant over £100m a year for precisely the sort of situation British steelworkers now face. The Germans, the French, the Dutch: they’ve all drawn down many millions apiece. The British? European commission officials told me this week that they had never so much as seen an application from the UK. Here’s a giant pot of money – into which Whitehall can’t even be bothered to dip its fingers.

Once our steel capacity is gone, it’s gone – and with it goes a big chunk of what’s left of our manufacturing base. Whole swaths of the country that have only just got off their backs after Thatcher’s de-industrial revolution will be knocked to the floor all over again.

The choice is stark. Westminster can sit on its hands, pretend it can’t do anything about the supposedly free market in steel (in which the single biggest player is the Chinese Communist party), and let tens of thousands of families go to the wall. Or our political class acts as if its job is actually to protect people from market fluctuations – and keep the steel industry afloat by extended bridging loans and capital investment in return for public stakes.

A return to British Leyland? No: a far cheaper and smaller rescue than RBS and HBOS. Free-market fundamentalists will decry this as a wage subsidy to steelworkers. But the alternative is to wind up paying far more in benefits to thousands of unemployed workers and their families. Besides, the state already shells out billions in hidden wage subsidies, through the tax credits and housing benefit that taxpayers give to employees of poverty-pay firms such as Sports Direct and Amazon.

What’s being proposed here is open, transparent support to employees in normally high-paying and high-skilled jobs. To keep a vital industry from disappearing for good. And to show that it’s not just the City that matters.

Tuesday, 1 July 2014

The real enemies of press freedom are in the newsroom

The principal threat to expression comes not from state regulation but from censorship by editors and proprietors

‘A political monoculture afflicts much of the press. Reports that might reveal a different side of the story remain unwritten.' Photograph: Tetra Images/Corbis

Three hundred years of press freedom are at risk, the newspapers cry. The government's proposed press regulator, they warn, threatens their independence. They have a respectable case, when you can extract it from the festoons of sticky humbug. Because of the shocking failures, so far, of self-regulation, I'm marginally in favour of the state solution. But I can also see the dangers.

Those who cry loudest against the regulator, however, recognise only one kind of freedom. In countries such as ours, the principal threat to freedom of expression comes not from government but from within the media. Censorship, in most cases, happens in the newsroom.

No newspaper has been more outspoken about what it calls "a chill over press freedom" than the Daily Mail. Though I agree with almost nothing it says, I would defend its freedom from state censorship as fiercely as I would defend the Guardian's. But, to judge by what it publishes, within the paper there is no freedom at all. There is just one line – echoed throughout its pages – on Europe, social security, state spending, tax, regulation, immigration, sentencing, trade unions and workers' rights. Labour is always too far to the left, even when it stands for nothing at all. Witness the self-defeating headline on Monday: "Red Ed 'won't unveil any policies in case they scare off voters'." Ed is red even when he's grey.

This suggests either that any article offering dissenting views is purged with totalitarian rigour, or general secretary Paul Dacre's terrified minions, knowing what is expected of them, never make such mistakes in the first place.

A similar political monoculture afflicts much of the press. Reports that might reveal a different side of the story remain unwritten. A free market in news is not the same as a free press, unless freedom is defined so narrowly that it refers only to the power of government, rather than to the power of money.

The monomania of the proprietors – or the editors they appoint in their own image – is compounded by an insidious, incestuous culture. The hacking trial revealed a world, as Suzanne Moore notes, of "sleepovers, dinners, flowers and presents ... in which genuine friendship is replaced by nightmare networking". A world in which one prime minister becomes godfather to a proprietor's child and another borrows an editor's horse, and an industry that is supposed to hold power to account brokers a seamless marriage between loot and boot.

On Mount Olympus, the gods pronounce upon issues that afflict only mortals: columnists with private-health plans support the savaging of the NHS; editors who educate their children privately heap praise upon Michael Gove, knowing that their progeny won't suffer his assault on state schools.

It doesn't matter, the defenders of these papers say: there are plenty of outlets, so balance can be found across the spectrum. But the great majority of papers, local as well as national, are owned by exceedingly rich people or their companies, and reflect their views. The owners, in the words of Max Hastings, once editor of the Daily Telegraph, are members of "the rich men's trade union", who "feel an instinctive sympathy for fellow multimillionaires". The field as a whole is unbalanced.

So pervasive are these voices that they seem to dominate even outlets they do not own. As Robert Peston, the BBC's economics editor, said last month, BBC News "is completely obsessed by the agenda set by newspapers ... if we think the Mail and Telegraph will lead with this, we should. It's part of the culture."

An analysis by researchers at Cardiff University found a deep and growing bias in the BBC in favour of bosses and against trade unions: five to one on the 6 o'clock news in 2007; 19 to one in 2012. Coverage of the banking crisis – caused by bankers – was overwhelmingly dominated, another study shows, by interviews with, er, bankers. As a result there was little serious challenge to their demand for bailouts and their resistance to regulation. Mike Berry, who conducted the research, says the BBC "tends to reproduce a Conservative, Eurosceptic, pro-business version of the world".

Last week, a brilliant and popular columnist for the Times, Simon Barnes, was sacked after 32 years. He was told that the paper could no longer afford his wages. But he wondered whether it might have something to do with the fierce campaign he's been waging against the owners of grouse moors, who have been wiping out the rare hen harriers that eat their quarry. It seems at first glance ridiculous: why would someone be sacked for grousing about grouse? But after experiencing the furious seigneurial affront with which a former senior editor at the Times, Magnus Linklater, responded to my enquiries about his 4,000-acre estate in Scotland and his failure to declare this interest while excoriating the RSPB for trying to protect hen harriers, I'm not so sure. This issue is of disproportionate interest to the rich men's trade union.

The two explanations might not be incompatible: if a paper owned by a crabby oligarch wanted to sack people for reasons of economy, it might look first at those engendering complaints among the owner's fellow moguls. The Times has yet to give me a comment.

Over the past few weeks, Private Eye has published several alarming claims about what it sees as censorship by the Telegraph on behalf of its advertisers. It says that extra stars have been added to film reviews, and that a story claiming HSBC had overstated its assets was spiked from on high so as not to offend the companies that pay the rent. The Telegraph told me: "We do not comment on inaccurate pieces from a satirical magazine like Private Eye."

Whatever the truth in these cases may be, it does not take journalists long to learn where the snakes lurk and the ladders begin. As the journalist Hannen Swaffer remarked long ago: "Freedom of the press ... is freedom to print such of the proprietor's prejudices as the advertisers don't object to." Yes, let's fight censorship: of the press and by the press.

Tuesday, 9 July 2013

Looking for a party funding scandal? Try David Cameron's Conservatives

We know how much Unite gives Labour, but finding out who writes the cheques for Conservative Central Office is more difficult

Len McCluskey, general secretary of Unite. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian

I've just been reading about a political party in hock to shadowy donors who enjoy easy access to its leadership and untold influence over its policies. It's scandalous stuff. That's right: I've just been reading about David Cameron's Conservative party.

Few activities are more congenial to the British commentariat than an afternoon's fox-hunting that can be moralised away as "grownup" debate. So it is with Ed Miliband and Len McCluskey. Even as they fire upon Ed for not being his brother, the pundits insist their real subject is party funding and who runs British politics. Yet mentions of the Tories' paymasters are inevitably brief and come with the gloss of "they're all as bad as each other".

Actually, they're not. Yes, some of the allegations about Falkirk are shaming. And it goes without saying that all three main parties are damagingly dependent on big donors; no Obama-style flood of 20s and 50s on this side of the water. But when it comes to concentration of funding, the opacity over where the cash comes from and the overlap between policy and donor interests, the Conservatives look far more corrupted.

We know how much Unite gives Labour because it's out in the open: all fully checkable on the Electoral Commission's website. Finding out who writes the cheques for Conservative Central Office is far harder. Cameron's funders seem to prefer channeling their money through conduits, or splitting the cash between multiple donors.

Through their forensic investigation into Tory funding, published just after the last general election, Stephen Crone and Stuart Wilks-Heeg discovered that some of the largest contributors would give a few hundred thousand: big, but not big enough to raise eyebrows. But then a funny thing could be spotted in the accounts: their wives and other family members would chip in, as well as their business ventures.

Take the JCB billionaire Sir Anthony Bamford, one of Cameron's favourite businessmen and a regular guest on the PM's trade missions abroad. Between 2001 and summer 2010, Wilks-Heeg and Crone found donations from Anthony Bamford, Mark Bamford, George Bamford, JCB Bamford Excavators, JCB Research, and JCB World Brands. Tot that up and you get a contribution to the Conservative party from the Bamford family of £3,898,900. But you'd need to be an expert sleuth with plenty of time and resources to tot it up.

One family: nearly £4m. Wilks-Heeg and Crone found that 15 of these families or "donor groups" account for almost a third of all Tory funding. They enjoy trips to Chequers, dinners in Downing Street and a friendly prime ministerial ear. Lord Irvine Laidlaw stuffed over £6m into Conservative pockets over a decade and, one of his former staffers told the Mail, liked to boast about his influence over party leaders: "William's [Hague] in my pocket".

Perhaps you're wondering why the Tories talked so tough on banking reform before election but have done so little since. That may have something to do with the money the City gives to them. According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, in 2010 donations from financial services accounted for over half of all Tory funding.

Three years ago, spread-betting boss Stuart Wheeler brazenly told MPs that "a party is going to take more notice of somebody who might give them lots of money than somebody who won't". He should know; he once gave the Conservatives a single donation of £5m. And certainly, the City has plenty to show for its investment. Across Europe, Angela Merkel, François Hollande and others are pushing ahead with plans for a Tobin tax or a small levy on financial transactions to start next year. Britain, on the other hand, is part of a small band of refuseniks, along with such other giants of financial regulation as Malta and Luxembourg.

One of the mysteries of this government is why George Osborne made a priority of cutting the 50p tax for the super-rich, thus handing the opposition a stick to beat him with. One possible answer to that is suggested by an FT report from November 2011 on hedge-fund donations to Osborne's party. "There probably aren't many votes in cutting the 50p top rate of tax," one major hedge fund donor told the paper, "but among those that give significant amounts to the party, it's a big issue, and that's probably why it's a big issue for the party too". Just four months later, at the next budget, the 50p rate was scrapped.

What, by contrast, has Uncle Len ever got from Ed Miliband? A promise of an end to the pay freeze for public servants? Nyet. A commitment to break from austerity? Nein. In spring 2010, the Telegraph claimed that Labour ministers "echoed the union's opposition to Kraft's takeover of Cadbury". This would be the takeover that actually went through. There are shades here of the MPs' expenses scandal, when the Tory schemes for lifting money from taxpayers were so baroque that they attracted less opprobrium than Labour parliamentarians claiming for bath plugs and blue movies. So it is with McCluskey's plan to fill Falkirk's constituency Labour party with Unite's Keystone Cops, even while hedgie Michael Hintze puts nearly £40,000 towards the chancellor's expenses alone and reaps the reward of a cut in his taxes.

But there's something else going on, too. Westminster and the press are still ruled by the idea that if workers' representatives seek to influence politics they must be bullies; while if capitalists get their way, then that's inevitably good for capitalism. Five years on from the banking crisis and all the evidence to the contrary, that really is a link that needs ending.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)