'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Corbyn. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Corbyn. Show all posts

Wednesday, 27 September 2017

Saturday, 2 September 2017

On Tory attempts to Activate British youth

Skepta will make a video on a skateboard park with his crew, singing ‘I’d do anything to please her, my Theresa, got a smile like Mona Lisa, as strong as Julius Caesar, as long as DUP get money to appease her’

Mark Steel in The Independent

This is a wonderful development: a youth group has spontaneously erupted to support the Conservatives, and calls itself Activate. It’s surprising this has taken so long, as you often hear young people in nightclub queues saying: “Listen up blud, a man Hammond getting bare fiscal growth yu get me, him one sick chancellor bruv.”

The plan must be for Chris Grayling to appear on Radio 1, interviewed about Brexit by Jameela Jamil, who says: “Wow, your riff with the Danes about butter tariffs was like totally AWESOME.”

At their conference, Conservative members will be told to wander into random locations chanting “Oooo Andrea Leadsom”, as this will result in young people joining in until it’s a Christmas number one featuring Stormzy in a duet with Amber Rudd.

Skepta will make a video on a skateboard park with his crew, singing: “I’d do anything to please her, my Theresa, got a smile like Mona Lisa, as strong as Julius Caesar, as long as DUP get money to appease her.”

Or the Conservatives may concede that the grime scene has committed itself to Labour, so they’ll have to co-opt a different style of youth music – such as thrash metal.

Then at fundraising garden fetes, the local Conservative MP can announce: “Thank you so much to Thomas and Frances Diddlesbury for such generous use of their grounds as ever, and for Lady Spiglington who surpassed herself this year with her delightful vol-au-vents and exquisite cranberry salad, and now I’m sure you’ll all join me in welcoming our special guest band to see us through the evening – let’s hear it for ‘Skull-crushing Death’.”

Then the singer will inform the crowd: “This first song is about the need for a tough stance on Brexit – sing along with the chorus that goes ‘They’re gonna crush your bones, crush your bones nnnnnygggggghaaaa vrrrrrr the European single market will lead us to Satan Satan Satan Luxembourg is run by Satan’.”

It’s typically astute that the spontaneous young Conservatives chose Activate as the name of their group, proving their sharp sense of youth culture, because like Momentum, this has the crucial quality of being three syllables.

They probably had lengthy discussions on which three-syllable word to choose, from a shortlist that included Caliphate, Urinate, Camper van, Rwanda and Wheelie-bin.

The next stage will be for Activate to collect millions of followers on Twitter, posting pithy youthful Tory tweets such as: “OMG! David Davis negotiation Gr8 massive love bro”, and “Bring back da hunt dem fox get merked proper lol.”

Because what the Conservatives have worked out, is that Jeremy Corbyn succeeded in appealing to millions of young people because he put stuff on Twitter.

No one was bothered about what he said on Twitter; it could be abolish tuition fees, or quadruple them – but the main thing is he said it on Twitter.

Then lots of young people said, “Oh look, like wow that old dude is on Twitter and shit”, and started singing his name.

So the Conservatives just have to copy the Corbyn image and they’ll win back the youth vote. Michael Fallon will grow a beard, and when he’s asked about Trident, he’ll say, “Talking of massive weapons, look at this beauty” – and display a prize-winning radish from his allotment.

This is why they’re promoting Jacob Rees-Mogg. Corbyn may be naïve enough to think he won popularity amongst the young by opposing zero-hour contracts, but the real reason was that young people are won over by anyone who seems a bit quirky.

So if Mogg doesn’t work, they’ll pick a leader from the people who go out on the first heats of Britain’s Got Talent, choosing someone who dresses as an ostrich and eats bees.

The Conservatives have a problem in trying to create an organisation that copies Momentum. It’s that Momentum didn’t just enrage the Tories – it also infuriated most Labour MPs, by backing someone who had spent his life on the edge of the Labour Party (usually in opposition to the leadership).

So it’s handy that they claim Activate has sprung up spontaneously, in a vast surge of natural youthful enthusiasm for working without a contract and having nowhere to live.

Amongst this energised adolescence is Activate’s National Chairman, Gary Markwell, who has suddenly decided to pull together these young forces who are crying out to be led.

He’s a reflection of how this is a grassroots movement, because up until now Gary has had no connection whatsoever with the hierarchy of the Conservative Party – except for being a campaign manager for Theresa May and Boris Johnson for ten years.

Now he’s suddenly decided to spontaneously set up Activate, in the same way that Nigel Farage might announce: “It’s never occurred to me before, but I think I might start campaigning to leave the EU.”

They’ve made an excellent start, because the way to win young people over, according to any faint study of the nation’s youth, must be to prove the Conservatives are the party of compassion and spirit and youthful energy.

So a Whatsapp group, described as a “precursor” to Activate, has been revealed to have had a fascinating discussion about the issue of “chavs”. An event in a working-class area is described as: “A fine opportunity to observe homo chav. And gas them all.”

It’s then suggested they could have medical experiments performed on them, to see how “they’re good at producing despite living rough”, and “substituted for animals for testing” and on and on.

That should do it. The Tories are already on 17 per cent of the under-24 vote, and Activate should guarantee it goes a long way down from there.

Mark Steel in The Independent

This is a wonderful development: a youth group has spontaneously erupted to support the Conservatives, and calls itself Activate. It’s surprising this has taken so long, as you often hear young people in nightclub queues saying: “Listen up blud, a man Hammond getting bare fiscal growth yu get me, him one sick chancellor bruv.”

The plan must be for Chris Grayling to appear on Radio 1, interviewed about Brexit by Jameela Jamil, who says: “Wow, your riff with the Danes about butter tariffs was like totally AWESOME.”

At their conference, Conservative members will be told to wander into random locations chanting “Oooo Andrea Leadsom”, as this will result in young people joining in until it’s a Christmas number one featuring Stormzy in a duet with Amber Rudd.

Skepta will make a video on a skateboard park with his crew, singing: “I’d do anything to please her, my Theresa, got a smile like Mona Lisa, as strong as Julius Caesar, as long as DUP get money to appease her.”

Or the Conservatives may concede that the grime scene has committed itself to Labour, so they’ll have to co-opt a different style of youth music – such as thrash metal.

Then at fundraising garden fetes, the local Conservative MP can announce: “Thank you so much to Thomas and Frances Diddlesbury for such generous use of their grounds as ever, and for Lady Spiglington who surpassed herself this year with her delightful vol-au-vents and exquisite cranberry salad, and now I’m sure you’ll all join me in welcoming our special guest band to see us through the evening – let’s hear it for ‘Skull-crushing Death’.”

Then the singer will inform the crowd: “This first song is about the need for a tough stance on Brexit – sing along with the chorus that goes ‘They’re gonna crush your bones, crush your bones nnnnnygggggghaaaa vrrrrrr the European single market will lead us to Satan Satan Satan Luxembourg is run by Satan’.”

It’s typically astute that the spontaneous young Conservatives chose Activate as the name of their group, proving their sharp sense of youth culture, because like Momentum, this has the crucial quality of being three syllables.

They probably had lengthy discussions on which three-syllable word to choose, from a shortlist that included Caliphate, Urinate, Camper van, Rwanda and Wheelie-bin.

The next stage will be for Activate to collect millions of followers on Twitter, posting pithy youthful Tory tweets such as: “OMG! David Davis negotiation Gr8 massive love bro”, and “Bring back da hunt dem fox get merked proper lol.”

Because what the Conservatives have worked out, is that Jeremy Corbyn succeeded in appealing to millions of young people because he put stuff on Twitter.

No one was bothered about what he said on Twitter; it could be abolish tuition fees, or quadruple them – but the main thing is he said it on Twitter.

Then lots of young people said, “Oh look, like wow that old dude is on Twitter and shit”, and started singing his name.

So the Conservatives just have to copy the Corbyn image and they’ll win back the youth vote. Michael Fallon will grow a beard, and when he’s asked about Trident, he’ll say, “Talking of massive weapons, look at this beauty” – and display a prize-winning radish from his allotment.

This is why they’re promoting Jacob Rees-Mogg. Corbyn may be naïve enough to think he won popularity amongst the young by opposing zero-hour contracts, but the real reason was that young people are won over by anyone who seems a bit quirky.

So if Mogg doesn’t work, they’ll pick a leader from the people who go out on the first heats of Britain’s Got Talent, choosing someone who dresses as an ostrich and eats bees.

The Conservatives have a problem in trying to create an organisation that copies Momentum. It’s that Momentum didn’t just enrage the Tories – it also infuriated most Labour MPs, by backing someone who had spent his life on the edge of the Labour Party (usually in opposition to the leadership).

So it’s handy that they claim Activate has sprung up spontaneously, in a vast surge of natural youthful enthusiasm for working without a contract and having nowhere to live.

Amongst this energised adolescence is Activate’s National Chairman, Gary Markwell, who has suddenly decided to pull together these young forces who are crying out to be led.

He’s a reflection of how this is a grassroots movement, because up until now Gary has had no connection whatsoever with the hierarchy of the Conservative Party – except for being a campaign manager for Theresa May and Boris Johnson for ten years.

Now he’s suddenly decided to spontaneously set up Activate, in the same way that Nigel Farage might announce: “It’s never occurred to me before, but I think I might start campaigning to leave the EU.”

They’ve made an excellent start, because the way to win young people over, according to any faint study of the nation’s youth, must be to prove the Conservatives are the party of compassion and spirit and youthful energy.

So a Whatsapp group, described as a “precursor” to Activate, has been revealed to have had a fascinating discussion about the issue of “chavs”. An event in a working-class area is described as: “A fine opportunity to observe homo chav. And gas them all.”

It’s then suggested they could have medical experiments performed on them, to see how “they’re good at producing despite living rough”, and “substituted for animals for testing” and on and on.

That should do it. The Tories are already on 17 per cent of the under-24 vote, and Activate should guarantee it goes a long way down from there.

Monday, 28 August 2017

Labour's new clarity on Brexit

The Independent

After months of confusion, contradictory statements and embarrassing media interviews, Labour has finally brought some clarity to its opaque policy on Brexit.

Sir Keir Starmer, the Shadow Brexit Secretary, has announced that the Opposition wants the UK to remain in the single market and customs union during a transitional phase after it leaves the EU in March 2019. During that period, Labour would accept the rules of both arrangements, including free movement – a departure from the party’s manifesto at the June election, which said “freedom of movement will end when we leave the EU”.

Significantly, Starmer does not rule out permanent membership of the single market and customs union after the transitional phase, if the EU agreed reforms on issues such as migration.

Labour’s move is overdue but welcome. Remaining in the EU’s main institutions for the transition is common sense. Such an “off the shelf” arrangement would provide the certainty and stability that business desperately needs, probably reducing the loss of investment and jobs. Despite that, Theresa May seeks a more complicated “bespoke” transitional deal, and insists the UK must leave the single market and customs union in 2019. The time and energy wasted on securing such an agreement would be much better spent on forging a long-term UK-EU partnership.

Although the Chancellor Philip Hammond would probably support an “off the shelf” transitional deal, Ms May seems worried that hardline Brexiteers would then accuse her of not implementing last year’s referendum decision. The Prime Minister should start to do what is right for her country rather than her party.

If she does not, it will fall to Parliament to ensure a sensible transition in line with Labour’s new approach. House of Commons arithmetic means that several of the 20 pro-European Conservatives would need to vote with opposition parties to secure single market and customs union membership for the transition. When MPs return to Westminster next month, these Tories will come under enormous pressure not to hand Jeremy Corbyn a landmark victory. But they should act in the national interest, even if Ms May does not.

Mr Corbyn, a long-standing Eurosceptic, should be applauded for his pragmatism. Although many working-class people in the North and Midlands voted Leave last year, voters did not endorse Ms May's hard Brexit vision in June. Labour is now unmistakably the party of soft Brexit.

Mr Corbyn has also acknowledged the support for close EU links among his MPs, party members and the trade unions – not to mention the adoring crowds at Glastonbury. Probably he senses that Labour’s new stance will enable it to make trouble for Ms May in Parliament. What he wants above all is another election; after his performance in June, who can blame him?

The Opposition now offers more clarity on the biggest issue facing the country than the Government. In a series of position papers in the past two weeks, ministers have set out to replicate much of what the UK currently enjoys after Brexit – on issues including customs, the Northern Ireland border, civil judicial cooperation and data protection. Which, of course, begs the question: why not stay in the single market and customs union, at least during the transitional phase?

Although Boris Johnson has been virtually silent on Brexit over the summer, the Government’s papers show that it has adopted his totally unrealistic “have-cake-and-eat-it” approach. This has naturally gone down badly with the 27 EU members. They have not fallen for a naked attempt to switch the focus on to a trade deal before “first round” matters are settled on citizens’ rights, Northern Ireland and an inevitable divorce payment on which the UK refuses to engage.

When negotiations resume in Brussels on Monday, David Davis, the Brexit Secretary, will urge his counterpart Michel Barnier to show more flexibility. Yet it is time for the Government to do just that. It would also do well to display the same clarity and pragmatism as Labour.

After months of confusion, contradictory statements and embarrassing media interviews, Labour has finally brought some clarity to its opaque policy on Brexit.

Sir Keir Starmer, the Shadow Brexit Secretary, has announced that the Opposition wants the UK to remain in the single market and customs union during a transitional phase after it leaves the EU in March 2019. During that period, Labour would accept the rules of both arrangements, including free movement – a departure from the party’s manifesto at the June election, which said “freedom of movement will end when we leave the EU”.

Significantly, Starmer does not rule out permanent membership of the single market and customs union after the transitional phase, if the EU agreed reforms on issues such as migration.

Labour’s move is overdue but welcome. Remaining in the EU’s main institutions for the transition is common sense. Such an “off the shelf” arrangement would provide the certainty and stability that business desperately needs, probably reducing the loss of investment and jobs. Despite that, Theresa May seeks a more complicated “bespoke” transitional deal, and insists the UK must leave the single market and customs union in 2019. The time and energy wasted on securing such an agreement would be much better spent on forging a long-term UK-EU partnership.

Although the Chancellor Philip Hammond would probably support an “off the shelf” transitional deal, Ms May seems worried that hardline Brexiteers would then accuse her of not implementing last year’s referendum decision. The Prime Minister should start to do what is right for her country rather than her party.

If she does not, it will fall to Parliament to ensure a sensible transition in line with Labour’s new approach. House of Commons arithmetic means that several of the 20 pro-European Conservatives would need to vote with opposition parties to secure single market and customs union membership for the transition. When MPs return to Westminster next month, these Tories will come under enormous pressure not to hand Jeremy Corbyn a landmark victory. But they should act in the national interest, even if Ms May does not.

Mr Corbyn, a long-standing Eurosceptic, should be applauded for his pragmatism. Although many working-class people in the North and Midlands voted Leave last year, voters did not endorse Ms May's hard Brexit vision in June. Labour is now unmistakably the party of soft Brexit.

Mr Corbyn has also acknowledged the support for close EU links among his MPs, party members and the trade unions – not to mention the adoring crowds at Glastonbury. Probably he senses that Labour’s new stance will enable it to make trouble for Ms May in Parliament. What he wants above all is another election; after his performance in June, who can blame him?

The Opposition now offers more clarity on the biggest issue facing the country than the Government. In a series of position papers in the past two weeks, ministers have set out to replicate much of what the UK currently enjoys after Brexit – on issues including customs, the Northern Ireland border, civil judicial cooperation and data protection. Which, of course, begs the question: why not stay in the single market and customs union, at least during the transitional phase?

Although Boris Johnson has been virtually silent on Brexit over the summer, the Government’s papers show that it has adopted his totally unrealistic “have-cake-and-eat-it” approach. This has naturally gone down badly with the 27 EU members. They have not fallen for a naked attempt to switch the focus on to a trade deal before “first round” matters are settled on citizens’ rights, Northern Ireland and an inevitable divorce payment on which the UK refuses to engage.

When negotiations resume in Brussels on Monday, David Davis, the Brexit Secretary, will urge his counterpart Michel Barnier to show more flexibility. Yet it is time for the Government to do just that. It would also do well to display the same clarity and pragmatism as Labour.

Friday, 11 August 2017

The west is gripped by Venezuela’s problems. Why does it ignore Brazil’s?

Reporters ask Jeremy Corbyn if he will condemn Nicolás Maduro. But the undemocratic abuses of Michel Temer aren’t flashy enough for the news cycle

Julia Blunck in The Guardian

Julia Blunck in The Guardian

‘Brazil has carried on as most stories about Latin America do: unnoticed and uncommented on.’ Riot police monitor protests against the government of Michel Temer in Brasilia, May 2017. Photograph: Evaristo Sa/AFP/Getty Images

Venezuela is the question on everyone’s lips. Rather, Venezuela is the question on reporters’ lips whenever they see Jeremy Corbyn: will he condemn the president, Nicolás Maduro? What is his position on Venezuela, and how does it affect his plans for Britain? The actual problems of Venezuela – a complex country with a long history that does not start with the previous president Hugo Chávez and certainly not with Jeremy Corbyn – are largely ignored or pushed aside. This is nothing new: most of the time, Latin America’s debates are seen through western lenses.

Venezuela is the question on everyone’s lips. Rather, Venezuela is the question on reporters’ lips whenever they see Jeremy Corbyn: will he condemn the president, Nicolás Maduro? What is his position on Venezuela, and how does it affect his plans for Britain? The actual problems of Venezuela – a complex country with a long history that does not start with the previous president Hugo Chávez and certainly not with Jeremy Corbyn – are largely ignored or pushed aside. This is nothing new: most of the time, Latin America’s debates are seen through western lenses.

Of course, the situation in Venezuela is deplorable and worrying. But it’s easy to see that concern about Maduro’s undemocratic abuses don’t necessarily come from actual concern for the welfare of Venezuelan people.

Nearby neighbour Brazil has not been analysed or debated at length, even as it demonstrates similar problems. The country’s president, Michel Temer, recently escaped measures that would see him put to trial in the supreme court by getting congress to vote them down. The case against Temer was not a flimsy or partisan one: there was a mountain of evidence, including recordings of him openly debating kickbacks with corrupt businessman Joesley Batista. That a president put into power under circumstances that could be, at best, described as dodgy, manages to remain in power by buying favours from Congress, even as he passes the harshest austerity measures in the world should be enough to raise a few eyebrows internationally. But that has not happened, and Brazil has carried on as most stories about Latin America do: unnoticed and uncommented on.

Part of this discrepancy is of course the bias toward what is flashy. Stories about sordid Congress deals are not that interesting to foreign audiences, and even many exhausted and demoralised Brazilians felt this was simply another addition to a long list of humiliations that began in 2015 when the economy started to sink.

Meanwhile, Venezuela has human conflict, the thing that produces exciting photography and think-pieces, sparks debate and crucially, draws clicks. There’s only so much attention to be gained talking about Temer’s undermining of democracy as it happens without noise, through chicanery and articulation by Brazil’s traditional power: the “Bible, beef and bullets” caucuses in Congress. Venezuela’s situation, however, is urgent, with tanks on the streets and opposition arrests.

Yet there is a subtext to why Brazil’s democracy is not as interesting, and why even Temer’s introduction of the military on to Rio de Janeiro’s streets to address a crime wave has prompted little response. Temer’s rule is one of hard capitalism and an ever-shrinking state. He has established a ceiling on public spending, slashed workers rights, and imposed a hard reform of retirement age.

Temer’s rise to power came as it became clear to big business that his predecessor, Dilma Rousseff, would not go far with austerity. They financed and stimulated protests – largely by rightly angry middle-class Brazilians at what they saw as widespread corruption – while Congress blocked Rousseff’s bills or sabotaged her agenda in other ways.

Latin American suffering is being played out as a proxy for debates in the UK

While Temer did not seize power through a violent coup, and the alliance between Rousseff’s Workers’ party and his notoriously dishonest and chronically double-crossing party was a largely self-inflicted wound, it bears remembering that Rousseff was ousted on a technicality so that Temer could solve the economy’s woes by making “difficult decisions”, a platform for which he had no electoral mandate.

And yet the economy continues to sink, as the unemployment rate soars to 13%. That narrative isn’t very convenient, though, and nobody is interested in making Brazil the representative case of how capitalism is an undemocratic system doomed to fail. And that is quite right: capitalism cannot be exclusively defined by Brazilian failures. The same should be true of socialism in Venezuela.

Somehow, though, the conversation about Venezuela is actually a conversation about something else. Latin American suffering is being played out as a proxy for debates in the UK. As the rightwing media claim, Jeremy Corbyn might not care very much about the thousands going hungry by Maduro’s hand – maybe he too thinks it is simply a consequence of American meddling – but it’s hard to believe that the British right is sincerely committed to the region’s stability and democracy. There has been very little said about Temer.

The failures of Temer do not, and should not be used to, excuse Maduro’s. Nor should we equate the two men in brutality. Yet, if you live in Brazil where public servants are teargassed for not being paid for five months, where indigenous rights activists and others are killed by rich farmers in unprecedented numbers, where several states declare bankruptcy because of a crash in oil prices, where the army is called upon to tackle protesters, you may wonder when your situation will be worth debating.

The answer is whenever it becomes politically convenient. In the end, British commentators and politicians on both the left and right aren’t just opportunistic when it comes to Latin American suffering, they are glad when it happens: it proves their point, whatever that may be. Our lives are just a detail.

Nearby neighbour Brazil has not been analysed or debated at length, even as it demonstrates similar problems. The country’s president, Michel Temer, recently escaped measures that would see him put to trial in the supreme court by getting congress to vote them down. The case against Temer was not a flimsy or partisan one: there was a mountain of evidence, including recordings of him openly debating kickbacks with corrupt businessman Joesley Batista. That a president put into power under circumstances that could be, at best, described as dodgy, manages to remain in power by buying favours from Congress, even as he passes the harshest austerity measures in the world should be enough to raise a few eyebrows internationally. But that has not happened, and Brazil has carried on as most stories about Latin America do: unnoticed and uncommented on.

Part of this discrepancy is of course the bias toward what is flashy. Stories about sordid Congress deals are not that interesting to foreign audiences, and even many exhausted and demoralised Brazilians felt this was simply another addition to a long list of humiliations that began in 2015 when the economy started to sink.

Meanwhile, Venezuela has human conflict, the thing that produces exciting photography and think-pieces, sparks debate and crucially, draws clicks. There’s only so much attention to be gained talking about Temer’s undermining of democracy as it happens without noise, through chicanery and articulation by Brazil’s traditional power: the “Bible, beef and bullets” caucuses in Congress. Venezuela’s situation, however, is urgent, with tanks on the streets and opposition arrests.

Yet there is a subtext to why Brazil’s democracy is not as interesting, and why even Temer’s introduction of the military on to Rio de Janeiro’s streets to address a crime wave has prompted little response. Temer’s rule is one of hard capitalism and an ever-shrinking state. He has established a ceiling on public spending, slashed workers rights, and imposed a hard reform of retirement age.

Temer’s rise to power came as it became clear to big business that his predecessor, Dilma Rousseff, would not go far with austerity. They financed and stimulated protests – largely by rightly angry middle-class Brazilians at what they saw as widespread corruption – while Congress blocked Rousseff’s bills or sabotaged her agenda in other ways.

Latin American suffering is being played out as a proxy for debates in the UK

While Temer did not seize power through a violent coup, and the alliance between Rousseff’s Workers’ party and his notoriously dishonest and chronically double-crossing party was a largely self-inflicted wound, it bears remembering that Rousseff was ousted on a technicality so that Temer could solve the economy’s woes by making “difficult decisions”, a platform for which he had no electoral mandate.

And yet the economy continues to sink, as the unemployment rate soars to 13%. That narrative isn’t very convenient, though, and nobody is interested in making Brazil the representative case of how capitalism is an undemocratic system doomed to fail. And that is quite right: capitalism cannot be exclusively defined by Brazilian failures. The same should be true of socialism in Venezuela.

Somehow, though, the conversation about Venezuela is actually a conversation about something else. Latin American suffering is being played out as a proxy for debates in the UK. As the rightwing media claim, Jeremy Corbyn might not care very much about the thousands going hungry by Maduro’s hand – maybe he too thinks it is simply a consequence of American meddling – but it’s hard to believe that the British right is sincerely committed to the region’s stability and democracy. There has been very little said about Temer.

The failures of Temer do not, and should not be used to, excuse Maduro’s. Nor should we equate the two men in brutality. Yet, if you live in Brazil where public servants are teargassed for not being paid for five months, where indigenous rights activists and others are killed by rich farmers in unprecedented numbers, where several states declare bankruptcy because of a crash in oil prices, where the army is called upon to tackle protesters, you may wonder when your situation will be worth debating.

The answer is whenever it becomes politically convenient. In the end, British commentators and politicians on both the left and right aren’t just opportunistic when it comes to Latin American suffering, they are glad when it happens: it proves their point, whatever that may be. Our lives are just a detail.

Thursday, 10 August 2017

Prime Minister Corbyn would face his own very British coup

The left underestimates the establishment backlash there would be if Corbyn were to reach No 10. They need to be ready

Owen Jones in The Guardian

‘In the 1970s, plots against Harold Wilson’s Labour government abounded.’ Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty Images

‘In the 1970s, plots against Harold Wilson’s Labour government abounded.’ Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty Images

As the Sunday Times political editor Tim Shipman put it to me, Theresa May is clinging on “because the Tories are genuinely fearful of a Corbyn government to a degree that goes far beyond usual opposition to Labour”. This panic is shared by other centres of economic and media power. It’s not simply Labour’s policy prospectus they fear. Three decades of neoliberalism – which promotes lower taxes on top earners and big business, privatisation, deregulation and weakened unions – has left them high on triumphalism. They find the prospect of even the most modest challenge to this order intolerable.

And unlike, say, the Attlee government, Labour’s leaders believe that political and social change cannot simply happen in parliament: people must be mobilised in their communities and workplaces to transform the social order. That, frankly, terrifies elite circles. Labour’s opposition to US dominance and a reorientation of Britain’s foreign policy is also viewed as simply unacceptable.

Here are threats to a Labour government to consider. First, undercover police officers. I’ve interviewed women who had relationships with undercover police officers with fake identities. They were climate change activists: the police had recruited individuals willing to sacrifice years of their lives and violate women to keep tabs on the environmental and direct action movements. If they were keeping tabs on small groups of activists, what of a movement with a genuine chance of assuming political power? Then there is the role of the civil service. Thatcherism transformed the attitudes of Britain’s state bureaucracy, particularly in the Treasury: the principles of free-market economics are treated by many senior civil servants as objective facts of life. One former Labour minister told me how, in the late 1990s, civil servants “informed” them that the Human Rights Act forbade controls on private rents. Those officials went on to propose benefit cuts that the Tories would later implement.

Every drop in the pound, every fall in the stock exchange will be hailed as a sign of economic chaos and ruin

Civil servants will tell Labour ministers that their policies are unworkable and must be watered down or discarded. Rather than blocking proposals, they will simply try to postpone them, hold never-ending reviews, call for limited trials – and then hope they are forgotten about. It will require savvy, streetfighting ministers to drive their agenda through.

Finally, those media outlets that cheered on Brexit and accused remainers of hysteria about the consequences, from day one of a Labour government will portray Britain as being in a state of chaos. Every drop in the pound, every fall in the stock exchange will be hailed as a sign of economic chaos and ruin. Demands for U-turns and a moderated agenda will become increasingly vociferous and backed by certain Labour MPs. The hope will be to disorientate, disillusion and divide Labour’s base.

All of these challenges can be overcome, but only by a formidable and permanently mobilised movement. An enthusiastic and inspired grassroots has already succeeded in depriving the Tories of their majority. It will play a critical role if Labour wins. International solidarity – particularly with the US and European left – will prove essential. Such a government will depend on a movement that constantly campaigns in local communities and workplaces. And yes, this is a column that will be dismissed as a tinfoil hat conspiracy. The British establishment has no interest in allowing a government that challenges its very existence to prove a success. These are the people in power whoever is in office, and they will bitterly resist any attempt to redistribute their wealth and influence. Better prepare, then – because an epic struggle for Britain’s future beckons.

Owen Jones in The Guardian

‘The British establishment has no interest in allowing a government that challenges its very existence to prove a success.’ Photograph: Justin Tallis/AFP/Getty Images

‘Do you really think the British state would just stand back and let Jeremy Corbyn be prime minister?” This was recently put to me by a prominent Labour figure, and must now be considered. Happily for me – as a Corbyn supporter who ended up fearing the project faced doom – this long-marginalised backbencher has a solid chance of entering No 10. If he makes it – and yes, the Tories are determined to cling on indefinitely to prevent it from happening – the establishment will wage a war of attrition in a determined effort to subvert his policy agenda and bring his government down.

You are probably imagining me hunched over my computer with a tinfoil hat. So consider this: there is a precedent for conspiracies against an elected British government, it is not so long ago, and it was waged against an administration that represented a significantly smaller threat to the existing order than that offered by Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour.

In the 1970s, plots against Harold Wilson’s Labour government abounded. The likes of Sir James Goldsmith and Lord Lucan believed Britain was in the grip of a leftwing conspiracy; while General Sir Walter Walker, the former commander of allied forces in northern Europe, was among those wanting to form anti-communist private armies. A plot, in which it is likely former intelligence officers and serving military officers were involved, went like this: Heathrow, the BBC and Buckingham Palace would be seized, Lord Mountbatten would be made interim prime minister, and the crown would publicly back such a regime to restore order. At the time, Wilson and his own private secretary were convinced about such a plot culminating in their arrest along with the rest of the cabinet. In Spycatcher, ex-MI5 assistant director Peter Wright openly wrote about a MI5-CIA plot against Wilson.

No, I do not believe a military coup against a Corbyn is plausible, although in 2015, a senior serving general did suggest “people would use whatever means possible, fair or foul”, including a “mutiny”, to block his defence plans. But there will be a determined operation to stop Corbyn ever becoming prime minister. The plots against Wilson were intertwined with cold war politics, and an establishment fear that Britain could defect from the western alliance. In the 1980s, the former Labour minister Chris Mullin wrote the novel A Very British Coup, inspired by the plots against Wilson, which explored an establishment campaign of destabilisation against a leftwing government. Mullin believes “MI5 has been cleared of dead wood” who would drive such plots. Maybe.

There is currently a plot to create a new “centrist” party that would secure a derisory vote share but potentially split the vote enough to keep the Tories in power. In an election campaign, the Tories will struggle with attack lines: “coalition of chaos” is now null and void, and the vitriol of the “get Corbyn” onslaught backfired. But expect a hysterical campaign of fear centred around warnings of economic Armageddon and corporate titans threatening to flee Britain’s shores.

‘Do you really think the British state would just stand back and let Jeremy Corbyn be prime minister?” This was recently put to me by a prominent Labour figure, and must now be considered. Happily for me – as a Corbyn supporter who ended up fearing the project faced doom – this long-marginalised backbencher has a solid chance of entering No 10. If he makes it – and yes, the Tories are determined to cling on indefinitely to prevent it from happening – the establishment will wage a war of attrition in a determined effort to subvert his policy agenda and bring his government down.

You are probably imagining me hunched over my computer with a tinfoil hat. So consider this: there is a precedent for conspiracies against an elected British government, it is not so long ago, and it was waged against an administration that represented a significantly smaller threat to the existing order than that offered by Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour.

In the 1970s, plots against Harold Wilson’s Labour government abounded. The likes of Sir James Goldsmith and Lord Lucan believed Britain was in the grip of a leftwing conspiracy; while General Sir Walter Walker, the former commander of allied forces in northern Europe, was among those wanting to form anti-communist private armies. A plot, in which it is likely former intelligence officers and serving military officers were involved, went like this: Heathrow, the BBC and Buckingham Palace would be seized, Lord Mountbatten would be made interim prime minister, and the crown would publicly back such a regime to restore order. At the time, Wilson and his own private secretary were convinced about such a plot culminating in their arrest along with the rest of the cabinet. In Spycatcher, ex-MI5 assistant director Peter Wright openly wrote about a MI5-CIA plot against Wilson.

No, I do not believe a military coup against a Corbyn is plausible, although in 2015, a senior serving general did suggest “people would use whatever means possible, fair or foul”, including a “mutiny”, to block his defence plans. But there will be a determined operation to stop Corbyn ever becoming prime minister. The plots against Wilson were intertwined with cold war politics, and an establishment fear that Britain could defect from the western alliance. In the 1980s, the former Labour minister Chris Mullin wrote the novel A Very British Coup, inspired by the plots against Wilson, which explored an establishment campaign of destabilisation against a leftwing government. Mullin believes “MI5 has been cleared of dead wood” who would drive such plots. Maybe.

There is currently a plot to create a new “centrist” party that would secure a derisory vote share but potentially split the vote enough to keep the Tories in power. In an election campaign, the Tories will struggle with attack lines: “coalition of chaos” is now null and void, and the vitriol of the “get Corbyn” onslaught backfired. But expect a hysterical campaign of fear centred around warnings of economic Armageddon and corporate titans threatening to flee Britain’s shores.

‘In the 1970s, plots against Harold Wilson’s Labour government abounded.’ Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty Images

‘In the 1970s, plots against Harold Wilson’s Labour government abounded.’ Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty ImagesAs the Sunday Times political editor Tim Shipman put it to me, Theresa May is clinging on “because the Tories are genuinely fearful of a Corbyn government to a degree that goes far beyond usual opposition to Labour”. This panic is shared by other centres of economic and media power. It’s not simply Labour’s policy prospectus they fear. Three decades of neoliberalism – which promotes lower taxes on top earners and big business, privatisation, deregulation and weakened unions – has left them high on triumphalism. They find the prospect of even the most modest challenge to this order intolerable.

And unlike, say, the Attlee government, Labour’s leaders believe that political and social change cannot simply happen in parliament: people must be mobilised in their communities and workplaces to transform the social order. That, frankly, terrifies elite circles. Labour’s opposition to US dominance and a reorientation of Britain’s foreign policy is also viewed as simply unacceptable.

Here are threats to a Labour government to consider. First, undercover police officers. I’ve interviewed women who had relationships with undercover police officers with fake identities. They were climate change activists: the police had recruited individuals willing to sacrifice years of their lives and violate women to keep tabs on the environmental and direct action movements. If they were keeping tabs on small groups of activists, what of a movement with a genuine chance of assuming political power? Then there is the role of the civil service. Thatcherism transformed the attitudes of Britain’s state bureaucracy, particularly in the Treasury: the principles of free-market economics are treated by many senior civil servants as objective facts of life. One former Labour minister told me how, in the late 1990s, civil servants “informed” them that the Human Rights Act forbade controls on private rents. Those officials went on to propose benefit cuts that the Tories would later implement.

Every drop in the pound, every fall in the stock exchange will be hailed as a sign of economic chaos and ruin

Civil servants will tell Labour ministers that their policies are unworkable and must be watered down or discarded. Rather than blocking proposals, they will simply try to postpone them, hold never-ending reviews, call for limited trials – and then hope they are forgotten about. It will require savvy, streetfighting ministers to drive their agenda through.

Finally, those media outlets that cheered on Brexit and accused remainers of hysteria about the consequences, from day one of a Labour government will portray Britain as being in a state of chaos. Every drop in the pound, every fall in the stock exchange will be hailed as a sign of economic chaos and ruin. Demands for U-turns and a moderated agenda will become increasingly vociferous and backed by certain Labour MPs. The hope will be to disorientate, disillusion and divide Labour’s base.

All of these challenges can be overcome, but only by a formidable and permanently mobilised movement. An enthusiastic and inspired grassroots has already succeeded in depriving the Tories of their majority. It will play a critical role if Labour wins. International solidarity – particularly with the US and European left – will prove essential. Such a government will depend on a movement that constantly campaigns in local communities and workplaces. And yes, this is a column that will be dismissed as a tinfoil hat conspiracy. The British establishment has no interest in allowing a government that challenges its very existence to prove a success. These are the people in power whoever is in office, and they will bitterly resist any attempt to redistribute their wealth and influence. Better prepare, then – because an epic struggle for Britain’s future beckons.

Wednesday, 14 June 2017

Monday, 12 June 2017

Jeremy Corbyn has won the first battle in a long war against the ruling elite

Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci understood that before taking power, the left must disrupt and defy common sense – just as Labour defeated the proposition that ‘Corbyn can’t win’

Paul Mason in The Guardian

To stop Jeremy Corbyn, the British elite is prepared to abandon Brexit – first in its hard form and, if necessary, in its entirety. That is the logic behind all the manoeuvres, all the cant and all the mea culpas you will see mainstream politicians and journalists perform this week.

And the logic is sound. The Brexit referendum result was supposed to unleash Thatcherism 2.0 – corporate tax rates on a par with Ireland, human rights law weakened, and perpetual verbal equivalent of the Falklands war, only this time with Brussels as the enemy; all opponents of hard Brexit would be labelled the enemy within.

But you can’t have any kind of Thatcherism if Corbyn is prime minister. Hence the frantic search for a fallback line. Those revolted by the stench of May’s rancid nationalism will now find it liberally splashed with the cologne of compromise.

Labour has, quite rightly, tried to keep Karl Marx out of the election. But there is one Marxist whose work provides the key to understanding what just happened. Antonio Gramsci, the Italian communist leader who died in a fascist jail in 1937, would have had no trouble understanding Corbyn’s rise, Labour’s poll surge, or predicting what happens next. For Gramsci understood what kind of war the left is fighting in a mature democracy, and how it can be won.

Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist theoretician and politician. Photograph: Laski Diffusion/Getty Images

And Gramsci would have understood the reasons here, too. When most socialists treated the working class as a kind of bee colony – pre-programmed to perform its historical role – Gramsci said: everyone is an intellectual. Even if a man is treated as “trained gorilla” at work, outside work “he is a philosopher, an artist, a man of taste ... has a conscious line of moral conduct”. [Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks]

On this premise, Gramsci told the socialists of the 1930s to stop obsessing about the state – and to conduct a long, patient trench warfare against the ideology of the ruling elite.

Eighty years on, the terms of the battle have changed. Today, you do not need to come up from the mine, take a shower, walk home to a slum and read the Daily Worker before you can start thinking. As I argued in Postcapitalism, the 20th-century working class is being replaced as the main actor – in both the economy and oppositional politics – by the networked individual. People with weak ties to each other, and to institutions, but possessing a strong footprint of individuality and rationalism and capacity to act.

What we learned on Friday morning was how easily such networked, educated people can see through bullshit. How easily they organise themselves through tactical voting websites; how quickly they are prepared to unite around a new set of basic values once someone enunciates them with cheerfulness and goodwill, as Corbyn did.

The high Conservative vote, and some signal defeats for Labour in the areas where working class xenophobia is entrenched, indicate this will be a long, cultural war. A war of position, as Gramsci called it, not one of manoeuvre.

But in that war, a battle has been won. The Tories decided to use Brexit to smash up what’s left of the welfare state, and to recast Britain as the global Singapore. They lost. They are retreating behind a human shield of Orange bigots from Belfast.

The left’s next move must eschew hubris; it must reject the illusion that with one lightning breakthrough we can envelop the defences of the British ruling class and install a government of the radical left.

The first achievable goal is to force the Tories back to a position of single-market engagement, under the jurisdiction of the European court of justice, and cross-party institutions to guide the Brexit talks. But the real prize is to force them to abandon austerity.

A Tory party forced to fight the next election on a programme of higher taxes and increased spending, high wages and high public investment would signal how rapidly Corbyn has changed the game. If it doesn’t happen; if the Conservatives tie themselves to the global kleptocrats instead of the interests of British business and the British people, then Corbyn is in Downing Street.

Either way, the accepted common sense of 30 years is over.

Paul Mason in The Guardian

To stop Jeremy Corbyn, the British elite is prepared to abandon Brexit – first in its hard form and, if necessary, in its entirety. That is the logic behind all the manoeuvres, all the cant and all the mea culpas you will see mainstream politicians and journalists perform this week.

And the logic is sound. The Brexit referendum result was supposed to unleash Thatcherism 2.0 – corporate tax rates on a par with Ireland, human rights law weakened, and perpetual verbal equivalent of the Falklands war, only this time with Brussels as the enemy; all opponents of hard Brexit would be labelled the enemy within.

But you can’t have any kind of Thatcherism if Corbyn is prime minister. Hence the frantic search for a fallback line. Those revolted by the stench of May’s rancid nationalism will now find it liberally splashed with the cologne of compromise.

Labour has, quite rightly, tried to keep Karl Marx out of the election. But there is one Marxist whose work provides the key to understanding what just happened. Antonio Gramsci, the Italian communist leader who died in a fascist jail in 1937, would have had no trouble understanding Corbyn’s rise, Labour’s poll surge, or predicting what happens next. For Gramsci understood what kind of war the left is fighting in a mature democracy, and how it can be won.

Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist theoretician and politician. Photograph: Laski Diffusion/Getty Images

Consider the events of the past six weeks a series of unexpected plot twists. Labour starts out polling 25% but then scores 40%. Its manifesto is leaked, raising major questions of competence, but it immediately boosts Corbyn’s popularity. Britain is attacked by terrorists but it is the Tories whose popularity dips. Diane Abbott goes sick – yet her majority rises to 30,000. Sitting Labour candidates campaign on the premise “Corbyn cannot win” yet his presence delivers a 10% boost to their own majorities.

None of it was supposed to happen. It defies political “common sense”. Gramsci was the first to understand that, for the working class and the left, almost the entire battle is to disrupt and defy this common sense. He understood that it is this accepted common sense – not MI5, special branch and the army generals – that really keeps the elite in power.

Once you accept that, you begin to understand the scale of Corbyn’s achievement. Even if he hasn’t won, he has publicly destroyed the logic of neoliberalism – and forced the ideology of xenophobic nationalist economics into retreat.

Brexit was an unwanted gift to British business. Even in its softest form it means 10 years of disruption, inflation, higher interest rates and an incalculable drain on the public purse. It disrupts the supply of cheap labour; it threatens to leave the UK as an economy without a market.

But the British ruling elite and the business class are not the same entity. They have different interests. The British elite are in fact quite detached from the interests of people who do business here. They have become middle men for a global elite of hedge fund managers, property speculators, kleptocrats, oil sheikhs and crooks. It was in the interests of the latter that Theresa May turned the Conservatives from liberal globalists to die-hard Brexiteers.

The hard Brexit path creates a permanent crisis, permanent austerity and a permanent set of enemies – namely Brussels and social democracy. It is the perfect petri dish for the fungus of financial speculation to grow. But the British people saw through it. Corbyn’s advance was not simply a result of energising the Labour vote. It was delivered by an alliance of ex-Ukip voters, Greens, first-time voters and tactical voting by the liberal centrist salariat.

The alliance was created in two stages. First, in a carefully costed manifesto Corbyn illustrated, for the first time in 20 years, how brilliant it would be for most people if austerity ended and government ceased to do the work of the privatisers and the speculators. Then, in the final week, he followed a tactic known in Spanish as la remontada – the comeback. He stopped representing the party and started representing the nation; he acted against stereotype – owning the foreign policy and security issues that were supposed to harm him. Day by day he created an epic sense of possibility.

The ideological results of this are more important than the parliamentary arithmetic. Gramsci taught us that the ruling class does not govern through the state. The state, Gramsci said, is just the final strongpoint. To overthrow the power of the elite, you have to take trench after trench laid down in their defence.

Last summer, during the second leadership contest, it became clear that the forward trench of elite power runs through the middle of the Labour party. The Labour right, trained during the cold war for such trench warfare, fought bitterly to retain control, arguing that the elite would never allow the party to rule with a radical left leadership and programme.

The moment the Labour manifesto was leaked, and support for it took off, was the moment the Labour right’s trench was overrun. They retreated to a second trench – not winning, with another leadership election to follow – but that did not exactly go well either.

As to the third trench line – the tabloid press and its broadcasting echo chamber – this too proved ineffectual. More than 12 million people voted for a party stigmatised as “backing Britain’s enemies”, soft on terror, with “blood on its hands”.

None of it was supposed to happen. It defies political “common sense”. Gramsci was the first to understand that, for the working class and the left, almost the entire battle is to disrupt and defy this common sense. He understood that it is this accepted common sense – not MI5, special branch and the army generals – that really keeps the elite in power.

Once you accept that, you begin to understand the scale of Corbyn’s achievement. Even if he hasn’t won, he has publicly destroyed the logic of neoliberalism – and forced the ideology of xenophobic nationalist economics into retreat.

Brexit was an unwanted gift to British business. Even in its softest form it means 10 years of disruption, inflation, higher interest rates and an incalculable drain on the public purse. It disrupts the supply of cheap labour; it threatens to leave the UK as an economy without a market.

But the British ruling elite and the business class are not the same entity. They have different interests. The British elite are in fact quite detached from the interests of people who do business here. They have become middle men for a global elite of hedge fund managers, property speculators, kleptocrats, oil sheikhs and crooks. It was in the interests of the latter that Theresa May turned the Conservatives from liberal globalists to die-hard Brexiteers.

The hard Brexit path creates a permanent crisis, permanent austerity and a permanent set of enemies – namely Brussels and social democracy. It is the perfect petri dish for the fungus of financial speculation to grow. But the British people saw through it. Corbyn’s advance was not simply a result of energising the Labour vote. It was delivered by an alliance of ex-Ukip voters, Greens, first-time voters and tactical voting by the liberal centrist salariat.

The alliance was created in two stages. First, in a carefully costed manifesto Corbyn illustrated, for the first time in 20 years, how brilliant it would be for most people if austerity ended and government ceased to do the work of the privatisers and the speculators. Then, in the final week, he followed a tactic known in Spanish as la remontada – the comeback. He stopped representing the party and started representing the nation; he acted against stereotype – owning the foreign policy and security issues that were supposed to harm him. Day by day he created an epic sense of possibility.

The ideological results of this are more important than the parliamentary arithmetic. Gramsci taught us that the ruling class does not govern through the state. The state, Gramsci said, is just the final strongpoint. To overthrow the power of the elite, you have to take trench after trench laid down in their defence.

Last summer, during the second leadership contest, it became clear that the forward trench of elite power runs through the middle of the Labour party. The Labour right, trained during the cold war for such trench warfare, fought bitterly to retain control, arguing that the elite would never allow the party to rule with a radical left leadership and programme.

The moment the Labour manifesto was leaked, and support for it took off, was the moment the Labour right’s trench was overrun. They retreated to a second trench – not winning, with another leadership election to follow – but that did not exactly go well either.

As to the third trench line – the tabloid press and its broadcasting echo chamber – this too proved ineffectual. More than 12 million people voted for a party stigmatised as “backing Britain’s enemies”, soft on terror, with “blood on its hands”.

And Gramsci would have understood the reasons here, too. When most socialists treated the working class as a kind of bee colony – pre-programmed to perform its historical role – Gramsci said: everyone is an intellectual. Even if a man is treated as “trained gorilla” at work, outside work “he is a philosopher, an artist, a man of taste ... has a conscious line of moral conduct”. [Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks]

On this premise, Gramsci told the socialists of the 1930s to stop obsessing about the state – and to conduct a long, patient trench warfare against the ideology of the ruling elite.

Eighty years on, the terms of the battle have changed. Today, you do not need to come up from the mine, take a shower, walk home to a slum and read the Daily Worker before you can start thinking. As I argued in Postcapitalism, the 20th-century working class is being replaced as the main actor – in both the economy and oppositional politics – by the networked individual. People with weak ties to each other, and to institutions, but possessing a strong footprint of individuality and rationalism and capacity to act.

What we learned on Friday morning was how easily such networked, educated people can see through bullshit. How easily they organise themselves through tactical voting websites; how quickly they are prepared to unite around a new set of basic values once someone enunciates them with cheerfulness and goodwill, as Corbyn did.

The high Conservative vote, and some signal defeats for Labour in the areas where working class xenophobia is entrenched, indicate this will be a long, cultural war. A war of position, as Gramsci called it, not one of manoeuvre.

But in that war, a battle has been won. The Tories decided to use Brexit to smash up what’s left of the welfare state, and to recast Britain as the global Singapore. They lost. They are retreating behind a human shield of Orange bigots from Belfast.

The left’s next move must eschew hubris; it must reject the illusion that with one lightning breakthrough we can envelop the defences of the British ruling class and install a government of the radical left.

The first achievable goal is to force the Tories back to a position of single-market engagement, under the jurisdiction of the European court of justice, and cross-party institutions to guide the Brexit talks. But the real prize is to force them to abandon austerity.

A Tory party forced to fight the next election on a programme of higher taxes and increased spending, high wages and high public investment would signal how rapidly Corbyn has changed the game. If it doesn’t happen; if the Conservatives tie themselves to the global kleptocrats instead of the interests of British business and the British people, then Corbyn is in Downing Street.

Either way, the accepted common sense of 30 years is over.

Sunday, 28 May 2017

British voters support every point on it, but the public square echoes with summary dismissal - The mystery of Jeremy Corbyn

Tabish Khair in The Hindu

How does one account for the fact that most U.K. voters support every point of the Labour manifesto, but the Tories, despite fumbles, are still leading in opinion polls by about 10 percentage points?

It is two weeks since the Labour manifesto was ‘leaked’. Immediately all the tabloids and most of the broadsheets went to town decrying the manifesto. It is the “second-longest suicide note in history”, they scoffed.

The hara-kiri reference was to the disastrous and divisive Labour manifesto of 1983, dubbed the “longest suicide note in history”. It is not an accurate reference. This 2017 manifesto is not protectionist like the 1983 one, and it promotes very restrained nationalisation. Moreover, the 1983 Labour manifesto was anti-Europe, anti-NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation), and uncompromisingly pacifist.

Not quite a ‘suicide note’

The 2017 manifesto is not anti-NATO; it even endorses NATO’s defence requirements. Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour leader, has repeatedly explained that sometimes collective military interventions can be justified, though he has also criticised the hasty wars of recent years.

Similarly, his plan to nationalise the railway services is not necessarily an ‘old-fashioned leftist idea’. It is a bid to bring government-controlled railways back onto a level playing field, thus undercutting the monopolies of private companies and providing commuters with more options. Most voters support this, as they do his plans to abolish education fees, provide more and cheaper housing, and improve the National Health Service. And yet Corbyn is expected to lose — narrowly by some sympathisers, hugely by his opponents. Why is that so?

Some of it has to do with Corbyn. He comes across as a severely honest but uncharismatic leader from the past, someone who engages with ideas (whether you agree or disagree with them) and not sound bites. The media does not like such politicians, as we know in India too. They provide boring copy.

The problem facing Labour is that of credibility: voters agree with their manifesto, but they do not believe it can be implemented. This is especially true of the ‘middle’ voters, who usually sway elections: many of them feel that Mr. Corbyn is idealistically leftist.

Deviating from core principles

It has to be said in Mr. Corbyn’s defence that for decades Labour has been diluting its pro-worker platform and the Tories increasing or sustaining their free-market platform. This has not been held against the Tories by many in the ‘middle’, while Labour, because of its compromises, has lost ground to the far right, even when it has won elections.

It is also a morbid world in which many ‘middle’ voters feel that something absolutely necessary for citizens cannot be done for fear of offending capital! Surely, a nation is not a corporation or an individual, both of which can go bankrupt, and a politician’s first responsibility is to citizens?

In that sense, Mr. Corbyn’s manifesto is a gamble — to attract more ordinary voters back into the folds of Labour, on the assumption that concrete policies will count for more than xenophobic rhetoric for many of them.

But are the policies outlined by Mr. Corbyn ‘sustainable’? Many papers and all tabloids seem to claim that they are not.

One way to answer this is to look at the general outline of what Mr. Corbyn is promising: he is promising to “transform” the lives of ordinary Britons. This, in effect, was also what Donald Trump had promised the Americans, and both Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron had promised the French.

Interestingly, at least some of the tabloids that have dismissed Mr. Corbyn’s promise were far less critical of similar claims to shake the cart by Mr. Trump. As interestingly, Mr. Trump, Mr. Macron (at least until he got elected) and Ms. Le Pen, in very different ways, had offered less concrete policies to induce us to believe that they could make any significant dent in the status quo.

Mr. Corbyn’s 2017 manifesto has clearer ideas: a pledge not to increase middle class taxes but to tax the top 5% more heavily, action to shrink the growing wage gap between employees and top management, a better housing policy than the Tories, etc. Even his position on the European Union seems to be more concrete than Tory leader Theresa May’s vacuous statement, redolent of colonial hubris, that she will be a “bloody difficult woman” during Brexit negotiations!

The media’s role

It remains perfectly valid to ask whether these Labour measures are enough or fully ‘sustainable’, but that is not what is being done by much of the U.K. media. Instead, the very effort is being dismissed.

Is it the case that, being paid huge salaries by the neo-liberal dream, which is becoming a nightmare for many, British media leaders (who are not necessarily editors) do not wish to question its myths. Especially the cardinal myth that ‘national bankruptcy’ can be avoided only by passing on public debts to individuals, as private debts, while nationally subsidising banks and corporations.

How does one account for the fact that most U.K. voters support every point of the Labour manifesto, but the Tories, despite fumbles, are still leading in opinion polls by about 10 percentage points?

It is two weeks since the Labour manifesto was ‘leaked’. Immediately all the tabloids and most of the broadsheets went to town decrying the manifesto. It is the “second-longest suicide note in history”, they scoffed.

The hara-kiri reference was to the disastrous and divisive Labour manifesto of 1983, dubbed the “longest suicide note in history”. It is not an accurate reference. This 2017 manifesto is not protectionist like the 1983 one, and it promotes very restrained nationalisation. Moreover, the 1983 Labour manifesto was anti-Europe, anti-NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation), and uncompromisingly pacifist.

Not quite a ‘suicide note’

The 2017 manifesto is not anti-NATO; it even endorses NATO’s defence requirements. Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour leader, has repeatedly explained that sometimes collective military interventions can be justified, though he has also criticised the hasty wars of recent years.

Similarly, his plan to nationalise the railway services is not necessarily an ‘old-fashioned leftist idea’. It is a bid to bring government-controlled railways back onto a level playing field, thus undercutting the monopolies of private companies and providing commuters with more options. Most voters support this, as they do his plans to abolish education fees, provide more and cheaper housing, and improve the National Health Service. And yet Corbyn is expected to lose — narrowly by some sympathisers, hugely by his opponents. Why is that so?

Some of it has to do with Corbyn. He comes across as a severely honest but uncharismatic leader from the past, someone who engages with ideas (whether you agree or disagree with them) and not sound bites. The media does not like such politicians, as we know in India too. They provide boring copy.

The problem facing Labour is that of credibility: voters agree with their manifesto, but they do not believe it can be implemented. This is especially true of the ‘middle’ voters, who usually sway elections: many of them feel that Mr. Corbyn is idealistically leftist.

Deviating from core principles

It has to be said in Mr. Corbyn’s defence that for decades Labour has been diluting its pro-worker platform and the Tories increasing or sustaining their free-market platform. This has not been held against the Tories by many in the ‘middle’, while Labour, because of its compromises, has lost ground to the far right, even when it has won elections.

It is also a morbid world in which many ‘middle’ voters feel that something absolutely necessary for citizens cannot be done for fear of offending capital! Surely, a nation is not a corporation or an individual, both of which can go bankrupt, and a politician’s first responsibility is to citizens?

In that sense, Mr. Corbyn’s manifesto is a gamble — to attract more ordinary voters back into the folds of Labour, on the assumption that concrete policies will count for more than xenophobic rhetoric for many of them.

But are the policies outlined by Mr. Corbyn ‘sustainable’? Many papers and all tabloids seem to claim that they are not.

One way to answer this is to look at the general outline of what Mr. Corbyn is promising: he is promising to “transform” the lives of ordinary Britons. This, in effect, was also what Donald Trump had promised the Americans, and both Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron had promised the French.

Interestingly, at least some of the tabloids that have dismissed Mr. Corbyn’s promise were far less critical of similar claims to shake the cart by Mr. Trump. As interestingly, Mr. Trump, Mr. Macron (at least until he got elected) and Ms. Le Pen, in very different ways, had offered less concrete policies to induce us to believe that they could make any significant dent in the status quo.

Mr. Corbyn’s 2017 manifesto has clearer ideas: a pledge not to increase middle class taxes but to tax the top 5% more heavily, action to shrink the growing wage gap between employees and top management, a better housing policy than the Tories, etc. Even his position on the European Union seems to be more concrete than Tory leader Theresa May’s vacuous statement, redolent of colonial hubris, that she will be a “bloody difficult woman” during Brexit negotiations!

The media’s role

It remains perfectly valid to ask whether these Labour measures are enough or fully ‘sustainable’, but that is not what is being done by much of the U.K. media. Instead, the very effort is being dismissed.

Is it the case that, being paid huge salaries by the neo-liberal dream, which is becoming a nightmare for many, British media leaders (who are not necessarily editors) do not wish to question its myths. Especially the cardinal myth that ‘national bankruptcy’ can be avoided only by passing on public debts to individuals, as private debts, while nationally subsidising banks and corporations.

Thursday, 11 May 2017

Noam Chomsky on worldwide anger

Labour party’s future lies with Momentum, says Noam Chomsky

Anushka Asthana in The Guardian

Professor Noam Chomsky has claimed that any serious future for the Labour party must come from the leftwing pressure group Momentum and the army of new members attracted by the party’s leadership.

In an interview with the Guardian, the radical intellectual threw his weight behind Jeremy Corbyn, claiming that Labour would be doing far better in opinion polls if it were not for the “bitter” hostility of the mainstream media. “If I were a voter in Britain, I would vote for him,” said Chomsky, who admitted that the current polling position suggested Labour was not yet gaining popular support for the policy positions that he supported.

“There are various reasons for that – partly an extremely hostile media, partly his own personal style which I happen to like but perhaps that doesn’t fit with the current mood of the electorate,” he said. “He’s quiet, reserved, serious, he’s not a performer. The parliamentary Labour party has been strongly opposed to him. It has been an uphill battle.”

He said there were a lot of factors involved, but insisted that Labour would not be trailing the Conservatives so heavily in the polls if the media was more open to Corbyn’s agenda. “If he had a fair treatment from the media – that would make a big difference.”

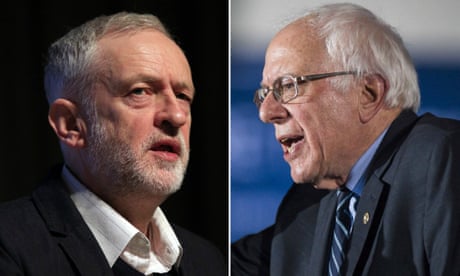

Asked what motivation he thought newspapers had to oppose Corbyn, Chomsky said the Labour leader had, like Bernie Sanders in the US, broken out of the “elite, liberal consensus” that he claimed was “pretty conservative”.

The academic, who is in Britain to deliver a lecture at the University of Reading on what he believes is the deteriorating state of western democracy, claimed that voters had turned to the Conservatives in recent years because of “an absence of anything else”.

“The shift in the Labour party under [Tony] Blair made it a pale image of the Conservatives which, given the nature of the policies and their very visible results, had very little appeal for good reasons.”

He said Labour needed to “reconstruct itself” in the interests of working people, with concerns about human and civil rights at its core, arguing that such a programme could appeal to the majority of people.

But ahead of what could be a bitter split within the Labour movement if Corbyn’s party is defeated in the June election, Chomsky claimed the future must lie with the left of the party. “The constituency of the Labour party, the new participants, the Momentum group and so on … if there is to be a serious future for the Labour party that is where it is in my opinion,” he said.

The comments came as Chomsky prepared to deliver a university lecture entitled Racing for the precipice: is the human experiment doomed?

He told the Guardian that he believed people had created a “perfect storm” in which the key defence against the existential threats of climate change and the nuclear age were being radically weakened.

“Each of those is a major threat to survival, a threat that the human species has never faced before, and the third element of this pincer is that the socio-economic programmes, particularly in the last generation, but the political culture generally has undermined the one potential defence against these threats,” he said.

Chomsky described the defence as a “functioning democratic society with engaged, informed citizens deliberating and reaching measures to deal with and overcome the threats”.

Professor Noam Chomsky has claimed that any serious future for the Labour party must come from the leftwing pressure group Momentum and the army of new members attracted by the party’s leadership.

In an interview with the Guardian, the radical intellectual threw his weight behind Jeremy Corbyn, claiming that Labour would be doing far better in opinion polls if it were not for the “bitter” hostility of the mainstream media. “If I were a voter in Britain, I would vote for him,” said Chomsky, who admitted that the current polling position suggested Labour was not yet gaining popular support for the policy positions that he supported.

“There are various reasons for that – partly an extremely hostile media, partly his own personal style which I happen to like but perhaps that doesn’t fit with the current mood of the electorate,” he said. “He’s quiet, reserved, serious, he’s not a performer. The parliamentary Labour party has been strongly opposed to him. It has been an uphill battle.”

He said there were a lot of factors involved, but insisted that Labour would not be trailing the Conservatives so heavily in the polls if the media was more open to Corbyn’s agenda. “If he had a fair treatment from the media – that would make a big difference.”

Asked what motivation he thought newspapers had to oppose Corbyn, Chomsky said the Labour leader had, like Bernie Sanders in the US, broken out of the “elite, liberal consensus” that he claimed was “pretty conservative”.

The academic, who is in Britain to deliver a lecture at the University of Reading on what he believes is the deteriorating state of western democracy, claimed that voters had turned to the Conservatives in recent years because of “an absence of anything else”.

“The shift in the Labour party under [Tony] Blair made it a pale image of the Conservatives which, given the nature of the policies and their very visible results, had very little appeal for good reasons.”

He said Labour needed to “reconstruct itself” in the interests of working people, with concerns about human and civil rights at its core, arguing that such a programme could appeal to the majority of people.

But ahead of what could be a bitter split within the Labour movement if Corbyn’s party is defeated in the June election, Chomsky claimed the future must lie with the left of the party. “The constituency of the Labour party, the new participants, the Momentum group and so on … if there is to be a serious future for the Labour party that is where it is in my opinion,” he said.