'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Saturday, 30 January 2021

The GameStop affair is like tulip mania on steroids

Towards the end of 1636, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the Netherlands. The concept of a lockdown was not really established at the time, but merchant trade slowed to a trickle. Idle young men in the town of Haarlem gathered in taverns, and looked for amusement in one of the few commodities still trading – contracts for the delivery of flower bulbs the following spring. What ensued is often regarded as the first financial bubble in recorded history – the “tulip mania”.

Nearly 400 years later, something similar has happened in the US stock market. This week, the share price of a company called GameStop – an unexceptional retailer that appears to have been surprised and confused by the whole episode – became the battleground between some of the biggest names in finance and a few hundred bored (mostly) bros exchanging messages on the WallStreetBets forum, part of the sprawling discussion site Reddit.

The rubble is still bouncing in this particular episode, but the broad shape of what’s happened is not unfamiliar. Reasoning that a business model based on selling video game DVDs through shopping malls might not have very bright prospects, several of New York’s finest hedge funds bet against GameStop’s share price. The Reddit crowd appears to have decided that this was unfair and that they should fight back on behalf of gamers. They took the opposite side of the trade and pushed the price up, using derivatives and brokerage credit in surprisingly sophisticated ways to maximise their firepower.

To everyone’s surprise, the crowd won; the hedge funds’ risk management processes kicked in, and they were forced to buy back their negative positions, pushing the price even higher. But the stock exchanges have always frowned on this sort of concerted action, and on the use of leverage to manipulate the market. The sheer volume of orders had also grown well beyond the capacity of the small, fee-free brokerages favoured by the WallStreetBets crowd. Credit lines were pulled, accounts were frozen and the retail crowd were forced to sell; yesterday the price gave back a large proportion of its gains.

To people who know a lot about stock exchange regulation and securities settlement, this outcome was quite inevitable – it’s part of the reason why things like this don’t happen every day. To a lot of American Redditors, though, it was a surprising introduction to the complexity of financial markets, taking place in circumstances almost perfectly designed to convince them that the system is rigged for the benefit of big money.

Corners, bear raids and squeezes, in the industry jargon, have been around for as long as stock markets – in fact, as British hedge fund legend Paul Marshall points out in his book Ten and a Half Lessons From Experience something very similar happened last year at the start of the coronavirus lockdown, centred on a suddenly unemployed sports bookmaker called Dave Portnoy. But the GameStop affair exhibits some surprising new features.

Most importantly, it was a largely self-organising phenomenon. For most of stock market history, orchestrating a pool of people to manipulate markets has been something only the most skilful could achieve. Some of the finest buildings in New York were erected on the proceeds of this rare talent, before it was made illegal. The idea that such a pool could coalesce so quickly and without any obvious sign of a single controlling mind is brand new and ought to worry us a bit.

And although some of the claims made by contributors to WallStreetBets that they represent the masses aren’t very convincing – although small by hedge fund standards, many of them appear to have five-figure sums to invest – it’s unfamiliar to say the least to see a pool motivated by rage or other emotions as opposed to the straightforward desire to make money. Just as air traffic regulation is based on the assumption that the planes are trying not to crash into one another, financial regulation is based on the assumption that people are trying to make money for themselves, not to destroy it for other people.

When I think about market regulation, I’m always reminded of a saying of Édouard Herriot, the former mayor of Lyon. He said that local government was like an andouillette sausage; it had to stink a little bit of shit, but not too much. Financial markets aren’t video games, they aren’t democratic and small investors aren’t the backbone of capitalism. They’re nasty places with extremely complicated rules, which only work to the extent that the people involved in them trust one another. Speculation is genuinely necessary on a stock market – without it, you could be waiting days for someone to take up your offer when you wanted to buy or sell shares. But it’s a necessary evil, and it needs to be limited. It’s a shame that the Redditors found this out the hard way.

Friday, 29 January 2021

Thursday, 28 January 2021

Wednesday, 27 January 2021

Covid lies cost lives – we have a duty to clamp down on them

Why do we value lies more than lives? We know that certain falsehoods kill people. Some of those who believe such claims as “coronavirus doesn’t exist”, “it’s not the virus that makes people ill but 5G”, or “vaccines are used to inject us with microchips” fail to take precautions or refuse to be vaccinated, then contract and spread the virus. Yet we allow these lies to proliferate.

We have a right to speak freely. We also have a right to life. When malicious disinformation – claims that are known to be both false and dangerous – can spread without restraint, these two values collide head-on. One of them must give way, and the one we have chosen to sacrifice is human life. We treat free speech as sacred, but life as negotiable. When governments fail to ban outright lies that endanger people’s lives, I believe they make the wrong choice.

Any control by governments of what we may say is dangerous, especially when the government, like ours, has authoritarian tendencies. But the absence of control is also dangerous. In theory, we recognise that there are necessary limits to free speech: almost everyone agrees that we should not be free to shout “fire!” in a crowded theatre, because people are likely to be trampled to death. Well, people are being trampled to death by these lies. Surely the line has been crossed?

Those who demand absolute freedom of speech often talk about “the marketplace of ideas”. But in a marketplace, you are forbidden to make false claims about your product. You cannot pass one thing off as another. You cannot sell shares on a false prospectus. You are legally prohibited from making money by lying to your customers. In other words, in the marketplace there are limits to free speech. So where, in the marketplace of ideas, are the trading standards? Who regulates the weights and measures? Who checks the prospectus? We protect money from lies more carefully than we protect human life.

I believe that spreading only the most dangerous falsehoods, like those mentioned in the first paragraph, should be prohibited. A possible template is the Cancer Act, which bans people from advertising cures or treatments for cancer. A ban on the worst Covid lies should be time-limited, running for perhaps six months. I would like to see an expert committee, similar to the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage), identifying claims that present a genuine danger to life and proposing their temporary prohibition to parliament.

While this measure would apply only to the most extreme cases, we should be far more alert to the dangers of misinformation in general. Even though it states that the pundits it names are not deliberately spreading false information, the new Anti-Virus site www.covidfaq.co might help to tip the balance against people such as Allison Pearson, Peter Hitchens and Sunetra Gupta, who have made such public headway with their misleading claims about the pandemic.

But how did these claims become so prominent? They achieved traction only because they were given a massive platform in the media, particularly in the Telegraph, the Mail and – above all – the house journal of unscientific gibberish, the Spectator. Their most influential outlet is the BBC. The BBC has an unerring instinct for misjudging where debate about a matter of science lies. It thrills to the sound of noisy, ill-informed contrarians. As the conservationist Stephen Barlow argues, science denial is destroying our societies and the survival of life on Earth. Yet it is treated by the media as a form of entertainment. The bigger the idiot, the greater the airtime.

Interestingly, all but one of the journalists mentioned on the Anti-Virus site also have a long track record of downplaying and, in some cases, denying, climate breakdown. Peter Hitchens, for example, has dismissed not only human-made global heating, but the greenhouse effect itself. Today, climate denial has mostly dissipated in this country, perhaps because the BBC has at last stopped treating climate change as a matter of controversy, and Channel 4 no longer makes films claiming that climate science is a scam. The broadcasters kept this disinformation alive, just as the BBC, still providing a platform for misleading claims this month, sustains falsehoods about the pandemic.

Ironies abound, however. One of the founders of the admirable Anti-Virus site is Sam Bowman, a senior fellow at the Adam Smith Institute (ASI). This is an opaquely funded lobby group with a long history of misleading claims about science that often seem to align with its ideology or the interests of its funders. For example, it has downplayed the dangers of tobacco smoke, and argued against smoking bans in pubs and plain packaging for cigarettes. In 2013, the Observer revealed that it had been taking money from tobacco companies. Bowman himself, echoing arguments made by the tobacco industry, has called for the “lifting [of] all EU-wide regulations on cigarette packaging” on the grounds of “civil liberties”. He has also railed against government funding for public health messages about the dangers of smoking.

Some of the ASI’s past claims about climate science – such as statements that the planet is “failing to warm” and that climate science is becoming “completely and utterly discredited” – are as idiotic as the claims about the pandemic that Bowman rightly exposes. The ASI’s Neoliberal Manifesto, published in 2019, maintains, among other howlers, that “fewer people are malnourished than ever before”. In reality, malnutrition has been rising since 2014. If Bowman is serious about being a defender of science, perhaps he could call out some of the falsehoods spread by his own organisation.

Lobby groups funded by plutocrats and corporations are responsible for much of the misinformation that saturates public life. The launch of the Great Barrington Declaration, for example, that champions herd immunity through mass infection with the help of discredited claims, was hosted – physically and online – by the American Institute for Economic Research. This institute has received money from the Charles Koch Foundation, and takes a wide range of anti-environmental positions.

It’s not surprising that we have an inveterate liar as prime minister: this government has emerged from a culture of rightwing misinformation, weaponised by thinktanks and lobby groups. False claims are big business: rich people and organisations will pay handsomely for others to spread them. Some of those whom the BBC used to “balance” climate scientists in its debates were professional liars paid by fossil-fuel companies.

Over the past 30 years, I have watched this business model spread like a virus through public life. Perhaps it is futile to call for a government of liars to regulate lies. But while conspiracy theorists make a killing from their false claims, we should at least name the standards that a good society would set, even if we can’t trust the current government to uphold them.

Tuesday, 26 January 2021

Indians have put their republic on a pedestal, forgotten to practise it each day

We have put the Indian republic on a high pedestal. In practice, though, the Indian republic is crumbling for the want of care. We publicly venerate the republic, even worship the Constitution, but we cannot care less about upholding it in practice. From the humblest citizen who wilfully violates traffic rules, to the middle-class businessman who cheats on taxes, to the public officials who line their pockets, to political leaders who use state power boundlessly, to judges and other constitutional authorities who bend in the direction of the prevailing winds, everyone pays respect to the Constitution. We all celebrate 26 January.

Yet the sum total of our actions leaves the republic weaker by the day. The crumbling started a couple of generations ago, slowly at first. Now, it is in a landslide. As I wrote in a column last month, “We are not even aware of the dangers of this deficiency…there is scarcely a whimper at the constant, popular undermining of the republic.”

One fell swoop

This sounds gloomy and pessimistic, and no one today can honestly say that they expect public officials — at any tier of government — to uphold their constitutional duty regardless of popular prejudices, political partisanship or monetary inducements. If we are asked to name public officials and institutions that can be relied upon to do their duty, come what may, we will perhaps find only a handful. Reversing the direction where the finger is pointed, do we “expect” public officials to do what they constitutionally ought to, or do what we want them to? If we do not see the difference between the two, we are guiltier than charged.

It is not difficult to see why the Indian republic is under stress. It enshrines values and norms that were — and unfortunately still are — far ahead of the society it sought to govern. In one fell swoop, it overturned a social order that had been in place for centuries. It recognised the primacy of the individual in a land where endogamous communities governed social life, and where hard hierarchies were entrenched. It sought to shape a modern polity based on civic nationalism, while trying to rub out ancient divisions of caste, creed and religion. As perhaps the only constitution that sought to enshrine a progressive social revolution — it suffered a backlash from the day it came into force. It did not help that the leaders of the new republic lost interest in educating its citizens about its importance, leaving it to desultory civics classes in high schools that involved memorising a few sentences without understanding any of them.

B.R. Ambedkar’s greatness lies as much in his prescience as in his powerful intellect. He was right on the mark when he said, “However good a Constitution may be, if those who are implementing it are not good, it will prove to be bad. However bad a Constitution may be, if those implementing it are good, it will prove to be good.” So it is important to heed his most important warning. He said that India risks losing its freedom again if we fail to do three things: first, “hold fast to constitutional methods of achieving our social and economic objectives”; second, not “to lay [our] liberties at the feet of even a great man, or to trust him with power which enable him to subvert [our] institutions”; and third, “we must make our political democracy a social democracy as well”.

Statues of Ambedkar often show him holding the Constitution in one hand, his other arm outstretched, finger pointed forward. The metaphor is brilliant. Yet we have put him on a pedestal too, making a public show of respecting him while doing the opposite of what he wanted us to do. It’s now more urgent than ever to follow the direction that he is seen pointing towards.

To preserve, protect and strengthen the Indian republic, we need to look no further than Ambedkar’s three guidances: insist on constitutional methods, avoid sycophancy, and recognise “liberty, equality and fraternity as the principles of life”.

A nation as large and diverse as India cannot painlessly execute a sudden change in direction. Individual citizens, public officials or leaders cannot change overnight. But we can make small changes at the margin. Everyone becoming just a little bit more law-abiding; just a little more sceptical about our leaders, parties and ideologies; and a little more conscious of our privileges and prejudices will get us back to ensuring that India is a living republic, a republic in practice than merely one on a pedestal.

Monday, 25 January 2021

As Joe Biden moves to double the US minimum wage, Australia can't be complacent

When I was writing about minimum wages for the Guardian six years ago, the United States only guaranteed workers US$7.25 an hour as a minimum rate of pay, dropping to a shocking US$2.13 for workers in industries that expect customers to tip (some states have higher minimum wages).

It is now 2021, and yet those federal rates remain exactly the same.

They’ve not moved since 2009. Meaningfully, America’s minimum wages have been in decline since their relative purchasing power peaked in 1968. Meanwhile, America’s cost of living has kept going up; the minimum wage is worth less now than it was half a century ago.

Now, new president Joe Biden’s $1.9tn pandemic relief plan proposes a doubling of the US federal minimum wage to $15 an hour.

It’s a position advocated both by economists who have studied comprehensive, positive effects of minimum wage increases across the world, as well as American unions of the “Fight for 15” campaign who’ve been organising minimum-wage workplaces demanding better for their members.

The logic of these arguments have been accepted across the ideological spectrum of leadership in Biden’s Democratic party. The majority of Biden’s rivals for the Democratic nomination – Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, Cory Booker and even billionaire capitalist Mike Bloomberg – are all on record supporting it and in very influential positions to advance it now.

In a 14 January speech, Biden made a simple and powerful case. “No one working 40 hours a week should live below the poverty line,” he said. “If you work for less than $15 an hour and work 40 hours a week, you’re living in poverty.”

And yet the forces opposed to minimum wage increases retain the intensity that first fought attempts at its introduction, as far back as the 1890s. America did not adopt the policy until 1938 – 31 years after Australia’s Harvester Decision legislated an explicit right for a family of four “to live in frugal comfort” within our wage standards.

But in both cases, the appreciation of the taste depends on your level of distraction from the meat. While wage-earning Australians may tut-tut an American framework that presently allows 7 million people to both hold jobs and live in poverty, local agitation persists for the Americanisation of our own established standards.

When I wrote about minimum wages six years ago, it was in the context of Australia’s Liberal government attempting to erode and compromise them. That government is still in power and that activism from the Liberals and their spruikers is still present. The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry campaigned against minimum wage increases last year. So did the federal government – using the economic downtown of coronavirus as a foil to repeat American mythologies about higher wages causing unemployment increases.

They don’t. The “supply side” insistence is that labour is a transactable commodity, and therefore subject to a law of demand in which better-paid jobs equate to fewer employment opportunities … but a neoclassical economic model is not real life.

We know this because some American districts have independently increased their minimum wages over the past few years, and data from places like New York and Seattle has reaffirmed what’s been observed in the UK and internationally. There is no discernible impact on employment when minimum wage is increased. An impact on prices is also fleeting.

As Biden presses his case, economists, sociologists and even health researchers have years of additional data to back him in. Repeated studies have found that increasing the minimum wage results in communities having less crime, less poverty, less inequality and more economic growth. One study suggested it helped bring down the suicide rate. Conversely, with greater wage suppression comes more smoking, drinking, eating of fatty foods and poorer health outcomes overall.

Only the threadbare counter-argument remains that improving the income of “burger-flippers” somehow devalues the labour of qualified paramedics, teachers and ironworkers. This is both classist and weak. Removing impediments to collective bargaining and unionisation is actually what enables workers – across all industries – to negotiate an appropriate pay level.

Australians have been living with the comparative benefits of these assumptions for decades, and have been spared the vicissitudes of America’s boom-bust economic cycles in that time.

But after seven years of Liberal government policy actively corroding standards into a historical wage stagnation, if Biden’s proposals pass, the American minimum wage will suddenly leapfrog Australia’s, in both real dollar terms and purchasing power.

It’ll be a sad day of realisation for Australia to see the Americans overtake us, while we try to comprehend just why we decided to get left behind.

Why you should ditch ‘follow your passion’ careers advice

Emma Jacobs in The FT

“Work is supposed to bring us fulfilment, pleasure, meaning, even joy,” writes Sarah Jaffe in her book, Work Won’t Love You Back. “The admonishment of a thousand inspirational social media posts to ‘do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life’ has become folk wisdom,” she continues.

Such platitudes suggest an essential truth “stretching back to our caveperson ancestors”. But these fallacies create “stress, anxiety and loneliness”. In short, the “labour of love . . . is a con”. This is the starting point of Ms Jaffe’s book, which goes on to show how the myth permeates diverse jobs and sectors.

---

---

The book serves as a timely reminder of the importance of re-evaluating that relationship. “The global pandemic made the brutality of the workplace more visible,” the author tells me over the phone from Brooklyn, New York. Ms Jaffe, who is a freelance journalist specialising in work, points out that the past year of job losses, anxiety about redundancy, and excessive workloads has demonstrated to workers the truth: their job does not love them.

Work is under scrutiny. The economic fallout of the pandemic has made a great many people desperate for paid work, disillusioned with their jobs or burnt out — and sometimes all three. It has illuminated the stark differences between those who can work from the safety of their homes and those who cannot, including shop workers, carers and medical professionals, who have to put themselves in potentially hazardous situations, often for meagre pay. The idea of self-sacrifice, and that you should put your clients, your patients or your students before yourself, Ms Jaffe says, “gets laid on very thick [with] teachers or nurses”.

Yet there are those in another category — artists and precarious academics — for whom work has always been deemed intrinsically rewarding and a form of self-expression. They are said to be lucky to have such jobs, because plenty of others are clamouring to take their place. Even here, the pandemic has changed perceptions. Social restrictions have curbed some of the aspects of white-collar work that made it rewarding, such as travel and meeting interesting people, that perhaps masked the repetition of daily tasks, the insecurity or poor conditions.

Meanwhile, Ms Jaffe says, a small number of workers, such as those who have been furloughed on full pay, have been given the time to think: what do I do with the time I used to devote to work? “It’s so beaten into us that we have to be productive,” says Ms Jaffe. “I've seen so many memes that are like, ‘if you haven’t written a novel in lockdown, [you’re] doing it wrong’.”

Among the affluent, work used to be something done by others, yet there have long been philosophical debates about whether it could be enjoyable. In the 1800s, Ms Jaffe points out in her book, the British designer and social campaigner William Morris pitched “three hopes” about work: “hope of rest, hope of product, hope of pleasure in the work itself”.

The decline of industrial jobs in the west, and the rise of the service economy, emphasised working for love. Nursing, food service and home healthcare, “draw on skills presumed to come naturally to women; they are seen as extensions of the caring work they are expected to do for their families”, Ms Jaffe writes. Among white-collar workers, the fetishisation of long hours in the late 1980s and 90s was accompanied by an individualistic capitalism. For many industries — notably, media — the idea of work as a form of self-actualisation intensified as security decreased.

Ms Jaffe says that there are overlapping experiences shared by those in the service sector who sit behind desks and those who stand on their feet all day. For example, the notion of the workplace as a family is a refrain in offices but it is most explicit for nannies. In the book, she tells the story of Seally, a nanny in New York who decided to live with her employers between Mondays and Fridays when the pandemic struck — leaving her own kids at home.

Seally told Ms Jaffe that she was worried about her own kids, whether they were doing their schoolwork properly: “At least I call and say, ‘Make sure you do your work’.” But she appreciates the importance of her job. “I love my work,” she said, “because my work is the silk thread that holds society together, making all other work possible”. The pandemic has reinforced the idea that the home is also a workplace and the author wants professionals who hire domestic workers and nannies to understand that and compensate accordingly for the critical role they play in facilitating their ability to do their jobs.

Perhaps the posterchild of insecure white-collar workers are interns, who have traditionally been unpaid. (In the UK, interns are eligible for pay if they are classed as a worker.) Too often, the book argues, interns have been given meaningless work with the prospect of a contract dangled in front of them, to no avail. Working conditions can also be poor — although few are as horrifying as the North Carolina zoo intern Ms Jaffe cites in the book who was killed by an escaped lion, “whose family told reporters she died ‘following her passion’ on her fourth unpaid internship”. The conditions for interns may be set back by the pandemic as so many graduates — and older workers hoping to switch industries — fight for jobs.

Ms Jaffe steers clear of advice. This is not a book that will guide readers on finding a job worthy of their devotion, though she knows that some glib tips would boost sales. “You’re told that you should love your job. Then if you don’t love your job, there’s something wrong with you,” she says. “[The problem] won’t be solved by quitting and finding a job you like better, or a different career, or deciding to just take a job that you don’t like.”

What she hopes is that people who have a nagging sense that their “job kind of sucks, they don't love it” will realise they are not alone. But they can do something about it, for instance joining a union or pushing for fewer hours. This needs to be supported by “a societal reckoning with jobs”. Do people need, for example, 24-hour access to McDonald’s and supermarkets, she asks?

Ms Jaffe wants people to imagine a society which is not organised “emotionally and temporally” around work. As she writes in the book: “What I believe, and want you to believe, too, is that love is too big and beautiful and grand and messy and human a thing to be wasted on a temporary fact of life like work.”

Sunday, 24 January 2021

On the Indian Farmers' Agitation for MSP

By Girish Menon

In this article I will try to explain the logic behind the Delhi protests by farmers demanding a Minimum Support Price (MSP).

If you are a businessman who has produced say 1000 units of a good; and are able to sell only 10 units at the price that you desired. Then it means you will have an unsold stock of 990 units. You now have a choice:

Either keep them in storage and sell it to folks who may come in the future and pay your asking price.

Or get rid of your unsold stock at whatever price the haggling buyers are willing to pay.

If you decide on the storage option then it follows that your goods are not perishable, it’s value does not diminish with age, you have adequate storage facilities and you have the resources to continue living even when most of your goods are unsold.

If you decide on the distress sale option it could mean that your goods are perishable and/or it’s value diminishes with age and/or you don’t have storage facilities and/or you are desperate to unload your stuff because for you whatever money you get today is important for your survival,

If one were to approach any small farmers’ output, I think such a farmer does not have the storage option available to him. Hence, he will have to sell his output to the intermediary at any price offered. This could mean a low price which results in a loss or a high price resulting in a profit to the farmer.

Whether the price is high or low depends on the volume of output produced by all farmers of the same output. And, no farmer is able to predict the likely future harvest price he would get at the moment he decides what crop to grow.

Thus a subsistence farmer, without storage facilities, is betting on the future price he could get at harvest time. This is a bet that destroys subsistence farmers from time to time when market prices turn really low due to a bumper harvest.

Subjecting subsistence farmers to ‘market forces’ means that some farmers will get bankrupted and be forced to leave their village and go to the city in search of a means of living. In many developed countries, governments have tried to prevent farmer exodus from villages by intervening and ensuring that farmers receive a decent return for their toils,

MSP is a government guarantee of a minimum price that protects farmers who cannot get their desired price at the market, The original draft of the farm law bills passed by the Indian Parliament has no mention of MSP. Also, in Punjab etc., some of these agitating farmers are already being supported with MSP by the state government and they fear that the new bills will take away their protection.

This is a simple explanation of the demand for MSP.

It must also be remembered that:

Unlike the subsistence farmer, the middleman who buys the farmers’ output is usually a part of a powerful cartel and who enjoys more market power than the farmer.

As depicted in ‘Peepli Live’ destitute farmers, if forced to leave their villages, will add to supply of cheap labour in an era of already high unemployment.

These destitute may squat on a city’s scarce public spaces and be an ‘eyesore’ to the better off city dwellers.

Some farmers may even contemplate suicide and this will produce less than desirable PR optics for any 'caring' government.

Saturday, 23 January 2021

Cheating on online exams

COVID-19 has made in-person exam proctoring impossible and so normal safeguards have disappeared. My inbox is full of anguished emails from university students across Pakistan bewailing the use of unfair and unethical means by their class fellows. Upon combining these complaints with those of my colleagues in various universities, and adding in my own online teaching experience, a frighteningly dismal picture emerges.

Almost every university student in this country cheats. Perhaps the actual figure is lower (80-90 per cent?) but it’s hard to tell. Many students say they are reluctant and would opt for honesty if there was a level playing field. But exercising virtue brings bad grades or even failure. Rare is the student with strong moral conviction — or perhaps lack of opportunity — who is not complicit.

A system full of holes is easy to beat. Not regarded as a significant moral crime, cheating was plentiful even in the days of in-person classes. But with online exams, the bottom has dropped out. Knowing their paychecks will be unaffected, many teachers don’t care what their students do. If one is somehow caught, cheating can always be deemed to be that student’s fault. After all, the pathways to cheating are so many.

Consider: while taking an exam the home-bound student supposedly sits facing his/her laptop camera without access to books, notes, or smartphone. Correspondingly, the teacher is supposed to be eagle-eyed, watching many students simultaneously on Zoom or MsTeams. Neither supposition is true. For example moving slightly out of the camera’s field of view allows the student to copy the question and insert it into the Google search bar of that laptop or a hidden smartphone. The answer pops up even before he/she fully finishes typing.

What of a question which Google cannot answer? Such slightly clever questions can indeed be devised by a conscientious professor. One shared with me how that worked out with her class of 30. In an exam none of her students got any question right. But, upon inspection, it turned out that every wrong answer belonged to one of six near-identical sets. Conclusion: the students were either sitting in the same room or had created WhatsApp groups with members messaging each other during the exam.

From a frustrated student who emailed me from an engineering university in Karachi, I learned something brand new after which I explored the matter further. Fact: there exists a plethora of commercial companies that will get you the required answer for almost every exam question. Among them are study aids Chegg, Quizlet, Course Hero and Brainly.

The ones I tried out with physics and math problems give instant answers. All you need to do is cut and paste the exam question into the indicated box. These answer services use artificial intelligence and operate without human intervention. While not cheap, they are affordable. According to my informant, students pool in to buy a subscription and then share answers over WhatsApp. More expensive are answer services staffed by human expert essay writers. The student need provide only basic information such as the topic and some course materials.

Special automated proctoring services, hired by overseas educational institutions, can catch cheaters who are taking their exam at home. These services block browsers from accessing forbidden websites, check to see if the student has contacted a friend or answer service, verify identity and geographical location, and see if the student is looking at flash cards or boards, etc. Some can even detect Bluetooth devices and suspicious movements of the test-takers’ head, keystrokes, and eyes.

Although such proctoring services probably have some value overseas, their utility in Pakistan is doubtful and they are not used. Apart from the cost, they also assume that a student has a quiet room, wide-angle webcam, and stable internet connection. This excludes rural areas but even in cities the last condition is not easily fulfilled.

Can any online exam work in these circumstances? The answer is: yes. A one-on-one oral exam over Skype or Zoom is the only totally safe method. But this is tedious for large classes and checks only a small aspect of his or her learning. To my knowledge, only a few university teachers use it.

Despite difficulties in evaluating students, online university education has worked reasonably well in some countries. Indeed, there are distinct advantages in going digital: an instructor’s recorded lectures can be rewound and reviewed at will for self-paced learning, students can ask questions online without feeling intimidated, and learning is available 24 hours a day. Additionally, a wealth of information and knowledge is just a click away and helps a student understand difficult points.

Why then is online learning failing so miserably in Pakistan? Why has fancy 21st-century education gadgetry not excited our students’ imagination? Why don’t our academic environments sparkle with energy? Two obvious reasons stare at us. First, the generally uninspiring online lectures delivered by teachers. Second, most students and many teachers have insufficient mastery over English to usefully engage with internet learning materials.

But a more serious, much deeper reason underlies this failure. Pakistan’s education system gives importance only to getting high grades, not to actually learning a subject. Even a good teacher — and these are few and far between — cannot make a student study, read books, meet schedules, and take responsibility. Real learning is purely voluntary. Largely a result of childhood training, it cannot be forced upon students. There is an age-old adage: education is all about learning to learn. The internet and Google have made this clear as never before. Every student today has good grades but only a few actually learn while in college or university.

Although our student body is hyper religious and regular in prayer, almost all are perfectly comfortable with cheating. But online testing cannot work unless cheating is viewed for what it is — a white-collar crime. Students willing to experiment, question, model, and wrestle with a problem alone can benefit from 21st-century online education. The bottom line: Pakistan’s education system must change direction. It must seek to create a proactive mindset and an ethical community.

Monday, 18 January 2021

Understanding Populism

In a March 7, 2010 essay for the New York Times, the American linguist and author Ben Zimmer writes, “When politicians fret about the public perception of a decision more than the substance of the decision itself, we’re living in a world of optics.”

On the other hand, according to Deborah Johnson in the June 2017 issue of Attorney at Law, a politician may have the best interests of his constituents in mind, but he or she doesn’t come across smoothly because optics are bad, even though the substance is good. Johnson writes that things have increasingly slid from substance to optics.

Optics in this context have always played a prominent role in politics. Yet, it is also true that their usage has grown manifold with the proliferation of electronic and social media, and, especially, of ‘populism.’ Populists often travel with personal photographers so that they can be snapped and proliferate images that are positively relevant to their core audience.

Pakistan’s PM Imran Khan relies heavily on such optics. He is also considered to be a populist. But then why did he so stubbornly refuse to meet the mourning families of the 11 Hazara Shia miners who were brutally murdered in Quetta? Instead, the optics space in this case was filled by opposition leaders, Maryam Nawaz and Bilawal Bhutto.

Nevertheless, this piece is not about why an optics-obsessed PM such as Khan didn’t immediately occupy the space that was eventually filled by his opponents. It is more about exploring whether Khan really is a populist? For this we will have to first figure out what populism is.

According to the American sociologist, Bart Bonikowski, in the 2019 anthology When Democracy Trumps Populism, populism poses to be ‘anti-establishment’ and ‘anti-elite.’ It can emerge from the right as well as the left, but during its most recent rise in the last decade, it has mostly come up from the right.

According to Bonikowski, populism of the right has stark ethnic or religious nationalist tendencies. It draws and popularises a certain paradigm of ‘authentic’ racial or religious nationalism and claims that those who do not have the required features to fit in this paradigm are outsiders and, therefore, a threat to the ‘national body.’ It also lashes out against established political forces and state institutions for being ‘elitist,’ ‘corrupt’ and facilitators of pluralism that is usurping the interests of the authentic members of the national body in a bid to undermine the ‘silent majority.’ Populism aspires to represent this silent majority, claiming to empower it.

Simply put, all this, in varying degrees, is at the core of populist regimes that, in the last decade or so, began to take shape in various countries — especially in the US, UK, India, Brazil, Turkey, Philippines, Hungary, Poland, Russia, Czech Republic and Pakistan. Yet, if anti-establishmentarian action and rhetoric is a prominent feature of populism, then what about populist regimes that are not only close to certain powerful state institutions, but were or are actually propped up by them? Opposition parties in Pakistan insist that Imran Khan’s party is propped up by the country’s military establishment, which is aiding it to remain afloat despite it failing on many fronts. The same is the case with the populist regime in Brazil.

Does this mean such regimes are not really populist? No. According to the economist Pranab Bardhan (University of California, Berkeley), even though populists share many similarities, populism’s shape can shift from region to region. Bardhan writes that characteristics of populism are qualitatively different in developed countries from those in developing countries. For example, whereas globalisation is seen in a negative light by populists in Europe and the US, a November 2016 survey published in The Economist shows that the people of 18 developing countries saw it positively, believing it gave their countries’ economies the opportunity to assert themselves.

Secondly, according to Bardhan, survey evidence suggests that much of the support for populist politics in developed countries is coming from less-educated, blue-collar workers, and from the rural backwaters. Populists in developing countries, by contrast, are deriving support mainly from the rising middle classes and the aspirational youth in urban areas. To Bardhan, in India, Pakistan, Turkey, Poland and Russia, symbols of ‘illiberal religious resurgence’ have been used by populist leaders to energise the upwardly-mobile or arriviste social groups.

He also writes that, in developed countries, populism is at loggerheads with the centralising state and political institutions, because it sees them as elitist, detached and a threat to local communities. But in developing countries, the populists have tried to centralise power and weaken local communities. To populists in developing countries, the main villains are not the so-called cold and detached state institutions, but ‘corrupt’ civilian parties. Ironically, while populism in the US is against welfare programmes, such programmes remain important to populists in developing countries.

Keeping this in mind, one can conclude that PM Khan is a populist, quite like his populist contemporaries in other developing countries. Despite nationalist rhetoric and his condemnatory understanding of colonialism, globalisation that promises foreign investment in the country is welcomed. His main base of support remains aspirational and upwardly-mobile urban middle-class segments. He often uses religious symbology and exhibitions of piety to energise this segment, providing religious context to what are actually Western ideas of state, governance, economics and nationalism. For example, the Scandinavian idea of the welfare state that he admires is defined as Riyasat-i-Madina (State of Madina).

Unlike populism in Europe and the US, populism in developing countries embraces the ‘establishment’ and, instead, turns its guns towards established political parties which it describes as being ‘corrupt.’ Khan is no different. He admires the Chinese system of central planning and economy and dreams of a centralised system that would seamlessly merge the military, the bureaucracy and his government into a single ruling whole. His urban middle-class supporters often applaud this ‘vision.’

Saturday, 16 January 2021

Friday, 15 January 2021

Conspiracy theorists destroy a rational society: resist them

John Thornhill in The FT

Buzz Aldrin’s reaction to the conspiracy theorist who told him the moon landings never happened was understandable, if not excusable. The astronaut punched him in the face.

Few things in life are more tiresome than engaging with cranks who refuse to accept evidence that disproves their conspiratorial beliefs — even if violence is not the recommended response. It might be easier to dismiss such conspiracy theorists as harmless eccentrics. But while that is tempting, it is in many cases wrong.

As we have seen during the Covid-19 pandemic and in the mob assault on the US Congress last week, conspiracy theories can infect the real world — with lethal effect. Our response to the pandemic will be undermined if the anti-vaxxer movement persuades enough people not to take a vaccine. Democracies will not endure if lots of voters refuse to accept certified election results. We need to rebut unproven conspiracy theories. But how?

The first thing to acknowledge is that scepticism is a virtue and critical scrutiny is essential. Governments and corporations do conspire to do bad things. The powerful must be effectively held to account. The US-led war against Iraq in 2003, to destroy weapons of mass destruction that never existed, is a prime example.

The second is to re-emphasise the importance of experts, while accepting there is sometimes a spectrum of expert opinion. Societies have to base decisions on experts’ views in many fields, such as medicine and climate change, otherwise there is no point in having a debate. Dismissing the views of experts, as Michael Gove famously did during the Brexit referendum campaign, is to erode the foundations of a rational society. No sane passenger would board an aeroplane flown by an unqualified pilot.

In extreme cases, societies may well decide that conspiracy theories are so harmful that they must suppress them. In Germany, for example, Holocaust denial is a crime. Social media platforms that do not delete such content within 24 hours of it being flagged are fined.

In Sweden, the government is even establishing a national psychological defence agency to combat disinformation. A study published this week by the Oxford Internet Institute found “computational propaganda” is now being spread in 81 countries.

Viewing conspiracy theories as political propaganda is the most useful way to understand them, according to Quassim Cassam, a philosophy professor at Warwick university who has written a book on the subject. In his view, many conspiracy theories support an implicit or explicit ideological goal: opposition to gun control, anti-Semitism or hostility to the federal government, for example. What matters to the conspiracy theorists is not whether their theories are true, but whether they are seductive.

So, as with propaganda, conspiracy theories must be as relentlessly opposed as they are propagated.

That poses a particular problem when someone as powerful as the US president is the one shouting the theories. Amid huge controversy, Twitter and Facebook have suspended Donald Trump’s accounts. But Prof Cassam says: “Trump is a mega disinformation factory. You can de-platform him and address the supply side. But you still need to address the demand side.”

On that front, schools and universities should do more to help students discriminate fact from fiction. Behavioural scientists say it is more effective to “pre-bunk” a conspiracy theory — by enabling people to dismiss it immediately — than debunk it later. But debunking serves a purpose, too.

As of 2019, there were 188 fact-checking sites in more than 60 countries. Their ability to inject facts into any debate can help sway those who are curious about conspiracy theories, even if they cannot convince true believers.

Under intense public pressure, social media platforms are also increasingly filtering out harmful content and nudging users towards credible sources of information, such as medical bodies’ advice on Covid.

Some activists have even argued for “cognitive infiltration” of extremist groups, suggesting that government agents should intervene in online chat rooms to puncture conspiracy theories. That may work in China but is only likely to backfire in western democracies, igniting an explosion of new conspiracy theories.

Ultimately, we cannot reason people out of beliefs that they have not reasoned themselves into. But we can, and should, punish those who profit from harmful irrationality. There is a tried-and-tested method of countering politicians who peddle and exploit conspiracy theories: vote them out of office.

Thursday, 14 January 2021

A Reluctant Feminist - Chapter 1

By Girish Menon

Laila, strapped to a seat in an Air Force AN-12 transport aircraft, hums

Waqt ne kiya kya haseen

situm,

Hum rahen na hum,

Tum rahen na tum.

(Time, you’ve tricked us, I’m not the old me, Nor you the old you)

The sound of the azaan

from her phone wakes her from her reverie; she unbuckles her seat belt, stands

up, stretches her weary limbs, sidesteps a coffin like wooden box in front of

her, goes to the open space on the aircraft, searches for the direction of

The captain yells: “Laila, Discharge time!”

Laila: Sir, how did he die?

Captain: Polonium poisoning, I think

The cargo doors of the plane open. Laila gets up and gives the coffin a push. It rolls off outside the aircraft. The aircraft veers upwards into the sky, lands at an airport and Laila emerges into a dark Mumbai evening at Kalina and calls for an Uber to take her home to Bhendi Bazaar.

Laila unlocks the door and quietly tiptoes to the safe in her bedroom. She removes the gift wrapped box from her knapsack, places it in the safe, locks it and rushes to the toilet. Abdul is watching TV from his armchair enjoying the song

Dil se tujhko bedilli

hai,

Mujhko hai dil ka

ghuroor,

Tu yeh mane ke na mane

Log manenge zaroor,

Yeh mera deewana pan hai

Ya mohabbat ka suroor,

Tu na pehchane to hai

Ye teri nazroon ka kasoor.

(You seem to deny your heart, While I am proud of my love, You may not admit it, The world will recognise it, It could be my irrationality, Or a hangover of love, If you cannot still spot it, You could be loveblind)

He switches off the TV, humming the rest of the song he walks wearily to the dining table, waiting for Laila. Laila emerges from the toilet, washes her hands and rushes to the dining table which has vessels of cooked food and two overturned plates and glasses. The maid warms the food.

Laila: Why haven't you eaten? It's not good for your diabetes.

Abdul: Nooo. You know that I don't like to eat alone.

Laila serves food for Abdul and herself

Laila: Ok, I'm sorry darling. Let's eat.

Abdul: What took you so long?

Laila: Routine, unending work. You know I can't say anything more.

Abdul: Was it a late parcel delivery?

Laila Smiles

Abdul: Ok, then can we discuss about

Laila: You know the nature of my job. What about

Abdul: She has failed in maths again. Her teacher has sent a note.

Laila: What about her tuition teacher? What is she doing despite the huge fees?

Abdul: Well! She says that without

Laila: How was your day?

Abdul: Hectic, I got in an hour before you and

Laila: You know I have to take an early flight to

Abdul: Why, I thought you were in the Maharashtra Police.

Laila: Yes, but Lakshmi Madam said that I was being considered for a special assignment.

Abdul: What special assignment? Have any of your assignments

ever been ordinary? You bring this up every time I mention

Laila: OH! That’s great! Let me finish this one assignment and then I will apply for VRS. It will also give me a pension for life.

Abdul: But you said the same thing two years ago.

Laila: I know! I know! Please trust me one last time.

They finish their meal in silence. Dump the dishes in the sink, jump into bed and start snoring.

Same time the next day Abdul watches the song

Dil ko teri hi tamanna

Dil ko hai tujhse hi

pyaar

Chahe tu aaye na aaye

Hum karenge intezaar

Yeh mera deewanapan hai

(My heart desires you, My heart loves you, Even if you don’t show up, I will wait for you, It could be my irrationality)

Laila opens the toilet door and joins Abdul at the dinner table.

Abdul: How was your meeting with Lakshmi madam?

Laila: Great! They have selected me over many applicants including that bloody conniving Sanjeev Bhatt.

Abdul: But he's IPS isn't he?

Laila: Yes, but they have chosen me over him. I have to report to camp in a week.

Abdul: What? Why and for how long?

Laila: You know it is a secret assignment and I will get to train at the top secret Pax Indica Centre. Lakshmi Madam has personally assured me that after this assignment I can retire at 35 with Secretary level pension.

Abdul: And have you said yes?

Laila: This is my one last assignment and soon we will get a

pension for life and I will be home to care for you and

Abdul: Do I have a say in this at all?

Laila: It's for us Abdul!

===End of Chapter 1

Wednesday, 13 January 2021

Modi govt is answerable to farmers, not the judiciary. SC’s mediation beyond its remit

Yogendra Yadav in The Print

In rejecting the Supreme Court-appointed expert committee to mediate between farmers and the Narendra Modi government, the farmers’ organisations have not only wisely sidestepped a possible trap, but they have also reaffirmed a basic principle of democratic accountability and responsible governance.

Let there be no confusion about it. The expert committee appointed by the SC is not meant to advise the court on technical matters of agricultural marketing or on the implications of the disputed agricultural laws. The order of the Supreme Court makes it clear that the committee is to facilitate negotiations between the government and farmers’ organisations: “The negotiations between the farmers’ bodies and the government have not yielded any result so far. Therefore, we are of the view that the constitution of a committee of experts in the field of agriculture to negotiate between the farmers’ bodies and the government of India may create a congenial atmosphere and improve the trust and confidence of the farmers.”

---Also watch

---

The court goes on to specify that the committee has been “constituted for the purpose of listening to the grievances of the farmers relating to the farm laws and the views of the government and to make recommendations.” Presumably, the committee will try to find a middle ground and advise the government on how the laws should be tinkered with in a way so as to satisfy both the government and the protesting farmers.

That is precisely why the farmers’ organisations had resisted, right from the beginning, the idea of any such committee. They have objected to being forced into binding mediation, questioned the instrument of a committee and suspected the composition of such a committee. On all three counts, their assessment has been proven right.

Beyond remit

First of all, the farmers have been suspicious of being pushed into binding mediations that they never asked for or consented to.

They have never said no to negotiations with the government. Sure, the talks with the government have been frustrating. The Modi government has been intransigent. Yet, that is the only site for negotiations in a democracy. In the last instance, elected representatives are there to speak to the people. They are accountable to the people and to the farmers. The courts are there to adjudicate between right and wrong, legal and illegal. The courts are not there to engage in give and take, which is a crucial part of any negotiation. That is why the courts are responsible to the Constitution and not accountable to the people. That is the logic of democratic governance. Any attempt to shift the site of negotiation from the government to the judiciary amounts to overturning this basic democratic logic.

The government’s keenness to shift this “headache” and the Supreme Court’s alacrity to take over has strengthened the resistance of the farmers. It needs to be underlined that the protesting farmers did not approach the court. Nor did the government, at least not on paper. The initial petitioners were third parties who wanted the court to evict the farmers from their protest site. The other set of petitioners questioned the constitutionality of the three laws and wanted these scrapped. None of the petitioners prayed for mediation from the court. Yet, from day one, that is what the court was interested in. The court dismissed, rightly so, the pleas asking for eviction of the protesting farmers. It recognised, again rightly so, the democratic rights of the farmers to engage in peaceful protest. As for the pleas, regarding the constitutional validity of the three laws, the court put this on the back burner saying that it will consider these at an appropriate time.

The Supreme Court could have expedited this process by setting a time frame within which it will decide upon the constitutional validity of these three laws. That would have been most appropriate. But it chose not to do so. Instead, the court chose to focus on a third issue beyond what was asked for by any party and beyond its legal remit. Farmers’ organisations were smart enough to resist this move from the beginning.

Technocrats can’t mediate

The second objection of the farmers’ organisations was to the very mechanism of a technical committee of experts. This idea was proposed by the Modi government in the very first round of negotiations held on 1 December, and the farmers rejected it there and then. Such a committee would be very useful to clarify a point of law, or to work out policy or fiscal implications of the proposed laws. Such a committee could also help work out the details of a compromise formula, once the basic framework is agreed to. But a technical committee cannot possibly work out the basic framework itself. Mediation is not done by technocrats. It is done by non-specialists who have some familiarity with the subject, but more importantly, who enjoy the trust and confidence of both parties. The Supreme Court-appointed committee of experts was never going to be that mechanism.

Dushyant Dave and the other three lawyers representing just eight out of 400+ farmers’ organisations involved in this protest were wise to keep away from the court’s deliberations on this issue.

A partisan committee

Finally, a committee is only as good as its members. It is no secret that the farmers’ organisations were apprehensive about the composition of a committee appointed by the court. The court’s order confirmed their worst fears. The process by which the court arrived at these four names left a lot to be desired, to put it mildly. The same court that chided the government for passing the farm laws without consulting the farmers adopted an even less transparent process to decide upon this committee. Names like P. Sainath and ex-CJIs were thrown around and quietly dispensed with. No one knows who suggested the four names. Little surprise then that the four names have invited disappointment and ridicule. Not because the four members are not respectable, but because these are arguably the four best advocates for the government’s position and the laws. That the court chose such a partisan committee to mediate between the farmers and the government has cast a shadow on itself.

Someone might ask: Forget the technicalities, but what’s wrong with the top court stepping in to resolve a deadlock? Well, that is possible provided the Supreme Court were to enjoy moral authority over and above its legal and constitutional powers. Such moral authority is commanded, not demanded.

Tuesday, 12 January 2021

Monday, 11 January 2021

Sunday, 10 January 2021

Saturday, 9 January 2021

Wednesday, 6 January 2021

Should bouncers be banned?

The current India tour of Australia has already had a bowling allrounder, a lower-order batsman, miss the T20I series because of a concussion. A key bowler is missing three Tests of the series with a broken arm. An opening batsman has missed out on a potential Test debut because of a hit to his head, which gave him his ninth concussion before the age of 22. All three players were hit by accurate, high-pace short-pitched bowling, which takes extreme skill, and some luck, to keep out.

The concussed bowling allrounder is now back. He scored a fifty at the MCG that frustrated the home side, who have been accustomed to rolling India over once they lose five wickets. India's additions from five-down in their last six innings in Test cricket: 64, 43, 48, 40, 48, 21. In Melbourne, the sixth wicket alone added 121 because this bowling allrounder hung around with his captain, one of only five specialist batsmen, a bold selection by the visiting side after 36 all out.

The fast bowler whose bouncer in the T20I ended up concussing this allrounder goes back to the bouncer plan in the Test. Experts on TV feel he has been too late getting there, that he has not been nasty enough. The allrounder shows he can handle himself, dropping his wrists and head out of the way of a couple of snorters, but he eventually plays a hook and is caught in the deep.

The next few batsmen are much less adept at handling this kind of bowling - the kind of players who have yielded low returns for India batting lower in the order. Bouncer after bouncer follows. One batsman has to call for help after getting hit in the chest. The other is hit twice on the forearm. All told, the bowler bowls 23 consecutive short balls at Nos. 7-9. Welcome to the land of "broken f****** elbows".

****

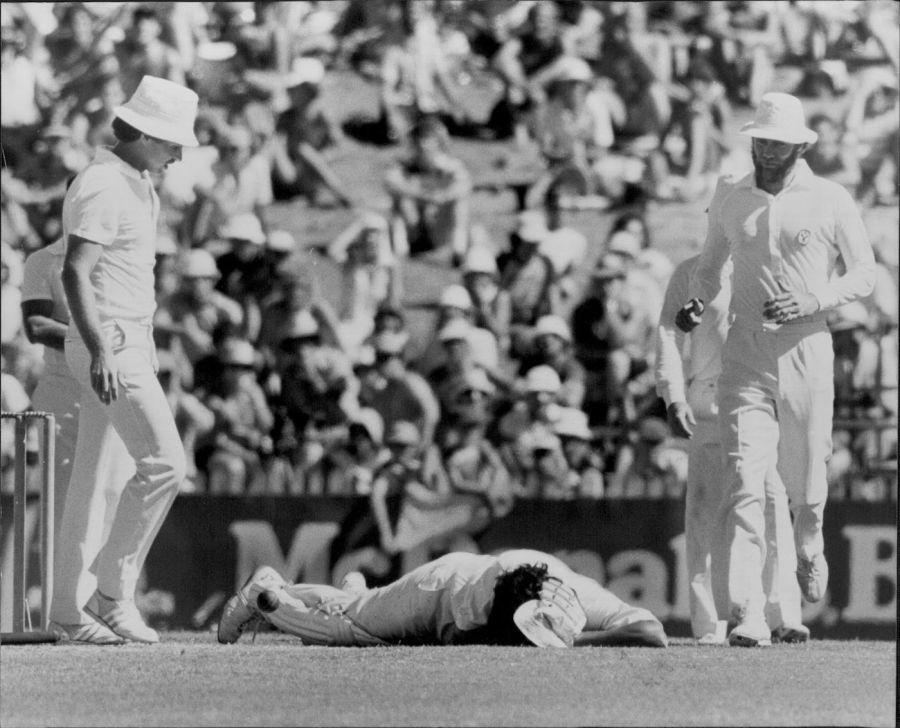

This is Australia. This is the land of tough, "hard but fair" cricket. This is also the place where there was an exemplary inquest into safety standards in cricket after the tragic death of young Phillip Hughes on a cricket field. Hughes was a specialist batsman, it was not a high-pressure Test match, and he was not facing an express bowler. He was hit in the side of the neck by a bouncer, just where the helmet ends.

It was a moment of awakening in cricket; of realisation that we have been extremely lucky, given the number of blows batsmen take, that we have not had too many such grave injuries. That it needn't be an inept tailender, that it needn't be 150kph, that it needn't be particularly nasty at first look, that any of the large number of bouncers we see and enjoy could be fatal for any of the practitioners of this highly skilled sport.

Imagine the number of concussions we have missed, now that we know how likely a blow to the head from a fast-paced bouncer is likely to cause one. In 2019, in the aftermath of the Steven Smith concussion, Mark Butcher told ESPNcricinfo's podcast Switch Hit how he faced a barrage from Tino Best and Fidel Edwards in 2004, wore one on the head, went off for bad light, didn't tell anyone how he felt, came back and batted with the same compromised helmet on. He is pretty certain he has batted through concussions. "You just batted on as long as you saw straight."

A concussion is a head injury that causes the head and the brain to shake back and forth quickly, not too unlike a pinball. It can make you dizzy, it can disorient you, it can slow your instincts down, its symptoms can show up at the time of impact or five minutes after, or an hour later, or at any time over the next couple of days. Just imagine the number of players who have continued risking what is potentially often a much graver "second impact", which can be caused in part by slowed instincts because of the first impact.

Australia is the land trying hard to normalise going off when you've had a head injury. It led cricket into instituting concussion substitutes. Six years on from Hughes' death, we are in the middle of a series between two highly skilled pace attacks capable of aiming high-speed, accurate short-pitched bowling at the bodies of batsmen.

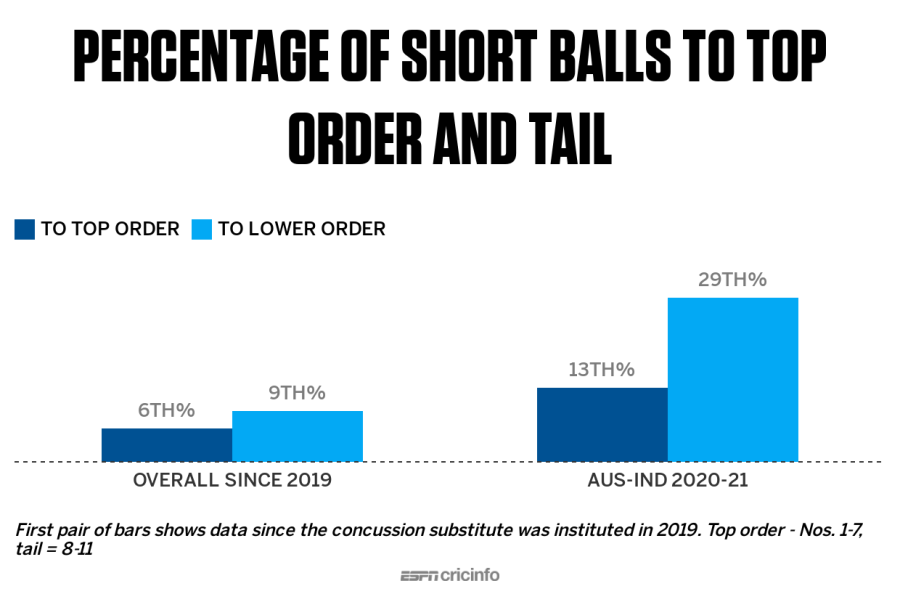

While there is conversation around making cricket safer, the threat for lesser-skilled batsmen is going up: 13% of deliveries from fast bowlers to those batting from Nos. 1 to 7 has been short in this series; for the lesser batsmen, batting from 8 to 11, this number has gone up to a whopping 29%, or roughly two short balls an over. The corresponding numbers in the recently concluded series between New Zealand and West Indies were 9% and 13%, which is still higher than the norm in Test cricket: 6% for batsmen 1 to 7 and 9% for the tail since concussions substitutes were introduced in July 2019.

****

Cricket is a weird sport. If you are a tail-end batsman, you often have to go out and let millions watch you do something you are inept at - sometimes hilariously so. And do it against opponents who are almost lethally good at doing what they are doing. The less you like it, the more you get it.

Opposing fast bowlers have stopped looking after each other now, what with protective equipment improving and lower-order batsmen increasingly placing higher prices on their wickets. When you are hit by a bouncer, you know there are former cricketers, some of whom you grew up idolising, waiting to label you soft should you show pain, let alone walk off.

When Ravindra Jadeja, the previously mentioned bowling allrounder, took a concussion substitute in the T20I, the predominant conversation was about the need to watch out against the misuse of the concussion substitute. Perhaps because Jadeja batted on for three more balls after he was hit - which was also a sign that not all teams take concussions seriously enough. Not every batsman has a stem guard at the back of his helmet, an appendage that might have saved Hughes' life.

Mark Taylor's response is a good summation of what the pundits thought: "The concussion rules are there to protect players. If they are abused, there's a chance it will go like the runner's rule. The reason runners were outlawed was because it started to be abused. It's up to the players to make sure they use the concussion sub fairly and responsibly. I'm not suggesting that didn't happen last night."

Taylor is a former Test captain, a former ICC cricket committee member, and a current administrator. He is better informed than many. During India's home season in 2019, when Bangladesh's batsmen were hit again and again in less-than-ideal viewing conditions in a hurriedly organised first day-night Test in India, commentators questioned their courage and called the repeated concussion tests ridiculous.

****

Mitchell Starc is the bowler whose bouncer resulted in the concussion to Jadeja. He is the one who bowled 23 short balls in a row at India's lower-order batsmen. He has had to deal with criticism from former players for being too soft at various points in his career. He saw his batsmen score just 195 after winning the toss in Melbourne, and was part of the bowling group that was asked once again to bail the team out. India batted extremely well, five catches went down, the pitch was easing out a little, and the deficit was growing. There was a microscope over Starc now.

Test-match cricket is no ordinary workplace. You have to do whatever is within the laws to get your wickets. Almost everyone is so good at what they do that errors have to be prised out, sometimes forced. Every weakness is preyed upon for whatever small advantage it might yield. It is not far-fetched to imagine Will Pucovski, the previously mentioned repeatedly concussed opening batsman, will be peppered if and when he makes his Test debut. This Indian team has fast bowlers who can give as good as they get, and they have got some from the Australian bowlers.

For over after over, fast bowlers do what their bodies are not biomechanically meant to be doing. You have to find a way to get a wicket. The bouncer is a legitimate ploy to get wickets, to mess with the batsman's footwork, to let them know they can't plonk the front foot down and keep driving or defending them, and even to send a message out to the remaining batsmen. That line between bowling bouncers to get wickets and doing it to hurt can get blurred. If you have an awesome power and no one has a way to tell with certainty that if you are always using it with good intent, there are chances you will end up misusing it once in a while.

It might sound extremely cynical, but if a blow to the head is highly likely to get a concussion substitute in, thus putting a front-line bowler out for at least a week and denying the opposition their ideal XI for the next Test, is it that difficult to imagine a fast bowler trying that extra bouncer before going for the full ball? Test match cricket is no ordinary workplace.

****

"I didn't want just that bloke to be scared," Len Pascoe said to me in 2015. "I wanted the guys in the dressing room to be scared too. If you got him scared, that's it. Often when I took wickets, I would get them in batches. One, two, bang. You just hit hard, hit hard."

Pascoe is a man after whom a hospital ward was named in the New South Wales town where he lived. Back then in the 1970s, every Saturday, Bankstown hospital would receive cricket victims in the Thomson-Pascoe ward. (And that despite being told years later by the groundsman at Bankstown that because of Thomson and Pascoe he used to make incredibly flat pitches.)

Pascoe was a young fast bowler, son of an immigrant brick carter, who grew up with racial abuse. To him, the man standing in the way of everything he wanted was the one across the 22 yards. He would do anything to get him out, and his captains and batsmen loved using him to do that. He bowled in an era when it was commonplace to hear chants of "Lillee Lillee, kill kill" at cricket rounds. In those days, any discussion around player safety was arguably mostly a ploy to neutralise West Indies, who had by then developed a pace battery that could match if not outdo any pace attack blow for blow.

The injuries Pascoe caused concerned him. Once, a batsman, George Griffith of South Australia, told him in a hospital after a day's play that had he been hit half an inch either side of where he had been, he wouldn't probably have been around to accept the apology. When Pascoe next hit a batsman badly - Sutherland's Glenn Bailey in a grade game, who then vomited blood - his mate Thomson had only recently lost his former flat-mate, 22-year-old Martin Bedkober, felled by a blow to the chest while batting in a Queensland grade match.

The young Pascoe kept doing it despite his discomfort, kept rationalising it to himself, comparing it to the risk a policeman or an army man takes, but when, at 32, he hit Sandeep Patil, a blow that knocked the batsman off his feet, he had had enough. He saw Patil stagger off the field, barely conscious, swaying this way and that despite support from the medical staff. Pascoe told his captain, Ian Chappell, he was walking away. Pascoe said Chappell asked him, "What if he hits you for six? Do you think he feels sorry for you?" That kept Pascoe going for another season but his heart was not in it.

Pascoe never injured another batsman. As a coach now, he teaches young bowlers to use the bouncer responsibly: bowl the first one well over the leg stump, only as a fact-finding mission to see where the feet are going. Bowl to get wickets, not to injure batsmen. It is important to instil fear, but it is equally important to not get addicted to instilling that fear.

****

Test cricket in New Zealand is played upside down. As matches progress, the pitches get slower and better to bat on. The best time to bat is the fourth innings. Everywhere else in the world, no matter how green the pitch, you win the toss and bat if no time has been lost to rain before the toss. New Zealand is the only place in the world where you win the toss and bowl first, because dismissals have to be manufactured in the second innings.

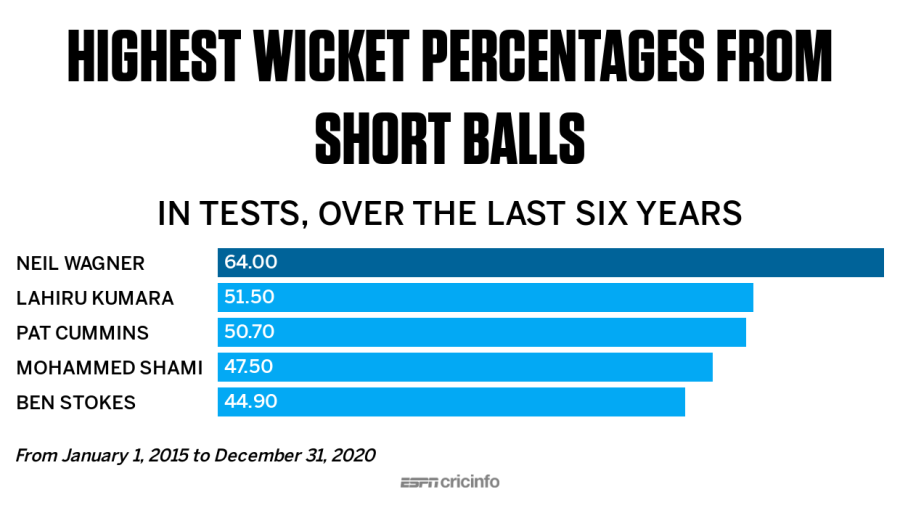

These conditions have given rise to a phenom called Neil Wagner. But for Wagner's style of bowling - persistent short balls between the chest and the head of the batsmen - there would be a high rate of draws in New Zealand. Since his debut, Wagner has bowled more short balls and taken more wickets with them than anyone else. He trains like a madman so that he can keep doing it over extremely long spells.

Two days after Starc possibly flirted with the line between bowling bouncers for wickets and bowling them for the hurt, Wagner goes to work on a dead pitch in the face of a stubborn Pakistan resistance to try to draw the Test. Running in on two broken toes, over an 11-over spell, Wagner bowls bouncer after bouncer from varied angles at varied heights and paces, and finally manages to get the wicket of century-maker Fawad Alam with a short ball from round the wicket.

The tail dig in their heels, and we go into the last hour with two wickets still in hand. Wagner figures the batsmen can block if he keeps pitching it up. So he digs it in short, and gets Shaheen Shah Afridi in the head in the 11th over of his spell. Over the next few overs, Afridi is tested repeatedly for a possible concussion.

This Wagner spell is compelling to watch. One man against the conditions, against his own hurting foot, against stubborn batsmen, trying to win his side a Test match in the dying minutes of the final day. The tail, emboldened by the improved protective equipment batsmen get to wear, braving blows to the body, trying to save a Test match. The fast bowler, fitter and stronger than he has ever been, able to sustain hostility and accuracy over longer spells than ever before.

ESPNcricinfo Ltd

ESPNcricinfo Ltd****

"The bowling of short-pitched deliveries is dangerous if the bowler's end umpire considers that, taking into consideration the skill of the striker, by their speed, length, height and direction they are likely to inflict physical injury on him/her. The fact that the striker is wearing protective equipment shall be disregarded."

The MCC leaves it to the umpires to decide what is dangerous. In most cases the umpires are professional enough to prevent things from getting bad enough to be visible to those watching from the outside. Often a quiet word when the bowler is walking back to their mark is enough. Yet the times that it does get out of hand, the umpire can call a dangerous delivery a no-ball, followed by a "first and final warning" and suspension from bowling should the bowler repeat the offence. It is near impossible to remember when such a no-ball was called, let alone a suspension.

The one time in recent memory when it did look like it got out of hand was when Brett Lee bowled four straight bouncers at Makhaya Ntini and Nantie Hayward in Adelaide back in 2002. Ntini was hit on the head twice before staggering through for a leg-bye, with Ian Chappell on air observing he was "perhaps a little dazed". After the fourth short ball, which chased Hayward's head as he backed away towards square leg, umpire Simon Taufel had a quiet word, resulting in two full deliveries.

Often under fire from commentators - former players themselves - and fans, umpires can be reluctant to draw any attention to themselves. The common refrain they have to deal with: "They have come to watch us play, not you umpire." Umpires don't want to be seen as overly officious - when it comes to policing player behaviour or in ball management or pitch management or ensuring player safety.

If the umpire steps in in the case of Starc, it will certainly be controversial in this high-profile contest. If he steps in to prevent Wagner from bouncing Afridi, he knows his one quiet word could end up being the difference between a win and a draw for New Zealand. The umpire has to ensure player safety but without compromising the integrity of the contest or attracting vitriol from former players and media. It is an extremely tight rope.

****

Those running the sport stand at a crucial crossroads. A lot of sports - especially those played by teams - have their roots in military training or colonisation. They were originally played to keep troops fit and ready for war, to hone a killer instinct for real war by indulging in a phony war; for voyeuristic entertainment; or to discipline the people of a new country so as to control and spread the right messages among the colonised. The war analogies endure but we have come a long way from sport's original purpose. Player safety standards might need to catch up.

One of the reasons bouncers are such a thrilling spectacle is the real danger they carry. At that pace and that height, you can't always control what is happening. To watch an expert batsman try to tame this force through technique, skill, courage and luck is a rush. There has to be a rush involved in bowling or facing them too. But only till someone gets hurt again, especially knowing as we do now what even a moderate-looking impact can do to a player's health. The rush gives way to unease pretty quickly these days.

Any new regulation that aims to limit this damage will be tricky to enforce. The existing regulations, which limit the number of short balls that are head-high (and not, for instance, chest-high) might need to be looked at too. In the last decade there were two recorded instances of club cricketers not surviving blows to the chest.

At first glance, the idea of regulating the use of bouncers seems ridiculous, given how integral the bouncer is to the game of cricket. There must have been a time, too, when the idea of a concussion substitute must have seemed ridiculous. When it must have been okay for players to compromise their safety by carrying on playing with potential brain injuries.