Vibhav Mariwala in The Print

Air India’s privatisation is finally underway, albeit, belatedly. Consequently, this has led to conversations around the planned economy, and in turn blamed the Socialist economy for India’s woes. These debates presume that India was forced into planning; this assumption undermines the country’s economic history, and disregards the role that Indian businesses played in shaping economic policy leading up to Independence.

In 1944, during the height of the Bengal famine, and with the seeming inevitability of Independence, J.R.D. Tata and seven other industrialists and executives — G.D. Birla, Purushottam Das Thakurdas, Ardeshir Shroff, Kasturbhai Lalbhai, Ardeshir Dalal, John Matthai, and Lal Shri Ram — came together to write a manifesto on the future of the Indian economy post-Independence. This was known as the Bombay Plan, or more formally called A Plan of Economic Development for India. The authors of the plan helped set up the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), supported the Indian National Congress (INC) during the Freedom struggle and even sat on the viceroy’s executive council during WWII.

View on economy

The Bombay Plan aimed to express the authors’ views on the post-Independence economy. It had the following components: a transition from agricultural domination to industrialisation; the allocation of resources through centralised planning, and the division of industries into ‘basic industries’, dominated by the State, and ‘consumer industries’, left to the private sector. From its outset, the plan acknowledged the primacy of the State in organising the economy and providing basic necessities to citizens. Historians such as Medha Kudaisya call the plan “a revolutionary idea” in State planning since it adopted a middle way for the private sector to coexist in a planned economy. On the other hand, Vivek Chibber in Locked in Place, argues that the plan was a way for businesses to entrench their own vested interests. (Vivek Chibber, Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India (Princeton, N.J. ; Princeton University Press, 2006), 86.)

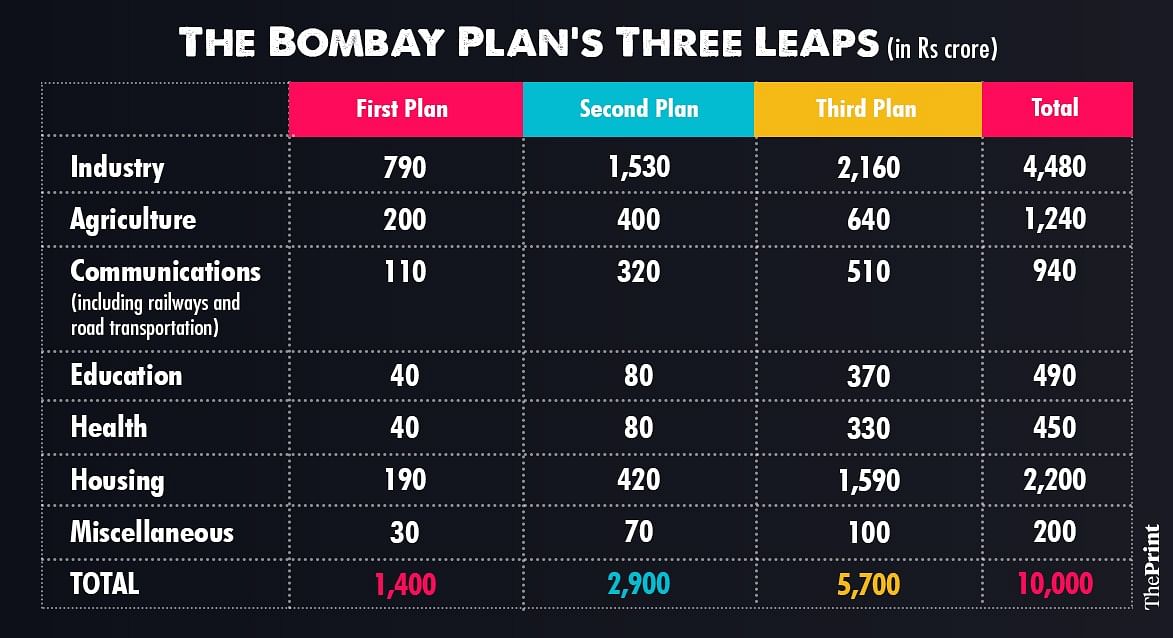

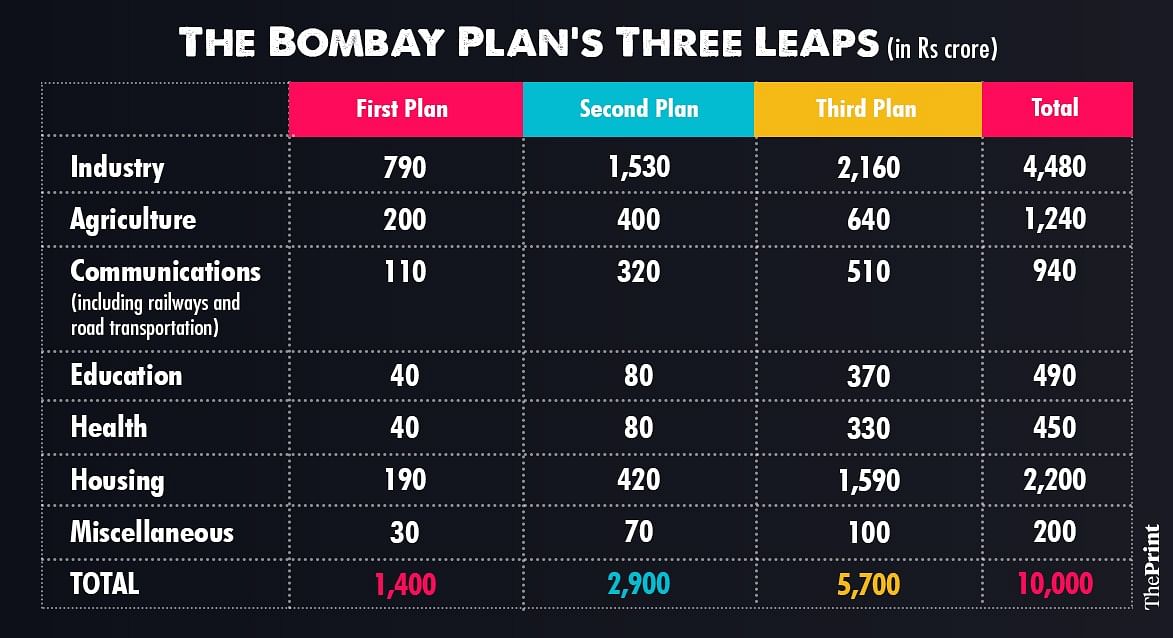

The principle objective of the plan was “to bring about a doubling of the present per capita income within a period of fifteen years from the time the plan comes into operation,” and increase production of power and capital goods. It then went on to define a reasonable living standard, cost of housing, clothing and food to individuals, housing requirements, and the provision of essential infrastructure like sewage treatment, water and electricity. It planned to achieve these aims in three ‘leaps’ spread over five years, analogous to the Five-Year Plans. The table below reflects these priorities.

Graphic by Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrint

Graphic by Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrint

The planners argued for a ‘mixed-economy’ model, where the government would take control of ‘basic industries,’ and the private sector would take charge of ‘consumer industries’. Basic industries included transportation, chemicals, power generation, and steel production. More significantly, they argued that nationalisation of basic industries could reduce income disparities and that the government had to prioritise basic industries over consumption to reduce poverty. The planners conclude this section by saying, “for the success of our economic plan that the basic industries, on which ultimately the whole economic development of the country depends, should be developed as rapidly as possible,” emphasising that the government needed to take a leading role in the economy to ensure their provision. This shows that the the business community conceded the centrality of the State in building India’s economy.

The plan was well received, with endorsements from FICCI, RBI Governor C.D. Deshmukh, and the viceroy, who in response to the plan document had established a Department of Planning and Development in 1944 (Tryst with Prosperity). Newspaper editorials in India and abroad supported the plan. The Glasgow Herald commended the planners for thinking about issues such as “public health, population control and education” that “Indian political leaders [could not] be induced to think about, however urgent.” The New York Times reported that “the main political factions in India do not seem to be coming forward with any such practical approaches,” reiterating the view that India’s political elite had not considered policy solutions to India’s problems. However, the plan document was criticised as well for being inaccurate and a vehicle for the elite to entrench their interests over the interests of the poor by K.T. Shah, general secretary of the 1937-38 NPC and Gulzarilal Nanda, future Planning Minister (1951-63)and other economists. Its calculations relied on statistics from 1932, making its assumptions highly outdated and it underestimated the costs of implementing its aims.

Influence on economic planning

The document was significant since it reframed debates on State planning — from arguing if the State should dominate the economy, to analysing the extent to which the State should be involved in the economy. Its influence on Indian economic planning is clearly seen in the immediate aftermath of WWII, and in the First and Second Five-Year Plans that prioritised agricultural development and industrial growth, respectively. It also paved the way for India to adopt a third way in structuring its political economy by providing an opportunity to the country to combine aspects of Western capitalism, Soviet planning, and Western Socialism, allowing India to chart its own independent course. To many, the plan was a way for businesses to signal to the INC leadership that it was willing to accept the supremacy of the State in the economy, while acknowledging the role of the private sector in supporting consumption activity.

Insisting that Nehruvian Socialism was the cause for India’s economic ills without acknowledging the political and economic contexts of post-Independence India reflects an incomplete understanding of India’s formative years after independence. The Bombay Plan is an essential document to understanding the events that led to the creation of India’s planned economy, and reiterates the view that planning was not imposed on the country, but was widely debated across the private and public sphere in the years leading up to Independence.

Air India’s privatisation is finally underway, albeit, belatedly. Consequently, this has led to conversations around the planned economy, and in turn blamed the Socialist economy for India’s woes. These debates presume that India was forced into planning; this assumption undermines the country’s economic history, and disregards the role that Indian businesses played in shaping economic policy leading up to Independence.

In 1944, during the height of the Bengal famine, and with the seeming inevitability of Independence, J.R.D. Tata and seven other industrialists and executives — G.D. Birla, Purushottam Das Thakurdas, Ardeshir Shroff, Kasturbhai Lalbhai, Ardeshir Dalal, John Matthai, and Lal Shri Ram — came together to write a manifesto on the future of the Indian economy post-Independence. This was known as the Bombay Plan, or more formally called A Plan of Economic Development for India. The authors of the plan helped set up the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), supported the Indian National Congress (INC) during the Freedom struggle and even sat on the viceroy’s executive council during WWII.

View on economy

The Bombay Plan aimed to express the authors’ views on the post-Independence economy. It had the following components: a transition from agricultural domination to industrialisation; the allocation of resources through centralised planning, and the division of industries into ‘basic industries’, dominated by the State, and ‘consumer industries’, left to the private sector. From its outset, the plan acknowledged the primacy of the State in organising the economy and providing basic necessities to citizens. Historians such as Medha Kudaisya call the plan “a revolutionary idea” in State planning since it adopted a middle way for the private sector to coexist in a planned economy. On the other hand, Vivek Chibber in Locked in Place, argues that the plan was a way for businesses to entrench their own vested interests. (Vivek Chibber, Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India (Princeton, N.J. ; Princeton University Press, 2006), 86.)

The principle objective of the plan was “to bring about a doubling of the present per capita income within a period of fifteen years from the time the plan comes into operation,” and increase production of power and capital goods. It then went on to define a reasonable living standard, cost of housing, clothing and food to individuals, housing requirements, and the provision of essential infrastructure like sewage treatment, water and electricity. It planned to achieve these aims in three ‘leaps’ spread over five years, analogous to the Five-Year Plans. The table below reflects these priorities.

Graphic by Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrint

Graphic by Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrintThe planners argued for a ‘mixed-economy’ model, where the government would take control of ‘basic industries,’ and the private sector would take charge of ‘consumer industries’. Basic industries included transportation, chemicals, power generation, and steel production. More significantly, they argued that nationalisation of basic industries could reduce income disparities and that the government had to prioritise basic industries over consumption to reduce poverty. The planners conclude this section by saying, “for the success of our economic plan that the basic industries, on which ultimately the whole economic development of the country depends, should be developed as rapidly as possible,” emphasising that the government needed to take a leading role in the economy to ensure their provision. This shows that the the business community conceded the centrality of the State in building India’s economy.

The plan was well received, with endorsements from FICCI, RBI Governor C.D. Deshmukh, and the viceroy, who in response to the plan document had established a Department of Planning and Development in 1944 (Tryst with Prosperity). Newspaper editorials in India and abroad supported the plan. The Glasgow Herald commended the planners for thinking about issues such as “public health, population control and education” that “Indian political leaders [could not] be induced to think about, however urgent.” The New York Times reported that “the main political factions in India do not seem to be coming forward with any such practical approaches,” reiterating the view that India’s political elite had not considered policy solutions to India’s problems. However, the plan document was criticised as well for being inaccurate and a vehicle for the elite to entrench their interests over the interests of the poor by K.T. Shah, general secretary of the 1937-38 NPC and Gulzarilal Nanda, future Planning Minister (1951-63)and other economists. Its calculations relied on statistics from 1932, making its assumptions highly outdated and it underestimated the costs of implementing its aims.

Influence on economic planning

The document was significant since it reframed debates on State planning — from arguing if the State should dominate the economy, to analysing the extent to which the State should be involved in the economy. Its influence on Indian economic planning is clearly seen in the immediate aftermath of WWII, and in the First and Second Five-Year Plans that prioritised agricultural development and industrial growth, respectively. It also paved the way for India to adopt a third way in structuring its political economy by providing an opportunity to the country to combine aspects of Western capitalism, Soviet planning, and Western Socialism, allowing India to chart its own independent course. To many, the plan was a way for businesses to signal to the INC leadership that it was willing to accept the supremacy of the State in the economy, while acknowledging the role of the private sector in supporting consumption activity.

Insisting that Nehruvian Socialism was the cause for India’s economic ills without acknowledging the political and economic contexts of post-Independence India reflects an incomplete understanding of India’s formative years after independence. The Bombay Plan is an essential document to understanding the events that led to the creation of India’s planned economy, and reiterates the view that planning was not imposed on the country, but was widely debated across the private and public sphere in the years leading up to Independence.