Nadeem Paracha in The Dawn

One point that supporters of Prime Minister Imran Khan really like to assert is that, “he is a self-made man.” They insist that the country should be led by people like him and not by those who were ‘born into wealth and power.’

According to the American historian Richard Hofstadter, such views are largely aired by the middle-classes. To Hofstadter, this view also has an element of ‘anti-intellectualism.’ In his 1963 book, Anti-intellectualism in American Life, Hofstadter writes that, as the middle-class manages to attain political influence, it develops a strong dislike for what it sees as a ‘political elite.’ But since this elite has more access to better avenues of education, the middle-class also develops an anti-intellectual attitude, insisting that, as a ruler, a self-made man is better than a better educated man.

Khan’s core support comes from Pakistan’s middle-classes. And even though he graduated from the prestigious Oxford University, he is more articulate when speaking about cricket — a sport that once turned him into a star — than about anything related to what he is supposed to be addressing as the country’s prime minister.

But many of his supporters do not have a problem with this, especially in contrast to his equally well-educated opponents, Bilawal Bhutto and Maryam Nawaz, who sound a lot more articulate in matters of politics. To Khan’s supporters, these two are from ‘dynastic elites’ who cannot relate to the sentiments of the ‘common people’ like a self-made man can.

It’s another matter that Khan is not the kind of self-made man that his supporters would like people to believe. He came from a well-to-do family that had roots in the country’s military-bureaucracy establishment. He went to prestigious educational institutions and spent most his youth as a socialite in London. Indeed, whereas the Bhutto and Sharif offsprings were born in wealth and power which is aiding their climb in politics, Khan’s political ambitions were carefully nurtured by the military-establishment.

Nevertheless, perhaps conscious of the fact that his personality is not suited to support an intellectual bent, Khan has positioned himself as a self-made man who appeals to the ways of the ‘common people.’ He doesn’t.

For example, wearing the national dress and using common everyday Urdu lingo does not cut it anymore. It did when the former PM Z.A. Bhutto did the same. But years after his demise in 1979, such ‘populist’ antics have become a worn-out cliche. The difference between the two is that Bhutto was a bonafide intellectual. Even his idea to present himself as a ‘people’s man’ was born from a rigorous intellectual scheme. However, Khan does appeal to that particular middle-class disposition that Hofstadter was writing about.

When he attempts to sound profound, his views usually appear to be a mishmash of theories of certain Islamic and so-called ‘post-colonial’ scholars. The result is rhetoric that actually ends up smacking of anti-intellectualism.

So what is anti-intellectualism? It is understood to be a view that is hostile to intellectuals. According to Walter E. Houghton, in the 1952 edition of the Journal of History of Ideas, the term’s first known usage dates back to 1881 in England, when science and ideas such as the ‘separation of religion and the state’, and the ‘supremacy of reason’ had gained momentum.

This triggered resentment in certain sections of the British society who began to suspect that intellectuals were formulating these ideas to undermine the importance of theology and long-held traditions.

According to the American historian Robert D. Cross, as populism started to become a major theme in American politics in the early 20th century, some mainstream politicians politicised anti-intellectualism as a way to portray themselves as men of the people. For example, US presidents Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) and Woodward Wilson (1913-1921) insisted that ‘character was more important than intellect.’

Across the 20th century, the politicised strand of anti-intellectualism was active in various regions. Communist regimes in China, the Soviet Union and Cambodia systematically eliminated intellectuals after describing them as remnants of overthrown bourgeoisie cultures. In Germany, the far-right intelligentsia differentiated between ‘passive intellectuals’ and ‘active intellectuals.’ Apparently, the passive intellectuals were abstract and thus useless whereas the active ones were ‘men of action.’ Hundreds of so-called passive intellectuals were harassed, exiled or killed in Nazi Germany.

In the 1950s, intellectuals in the US began to be suspected by firebrand members of the Republican Party of serving the interests of communist Russia. In former East Pakistan, hundreds of intellectuals were violently targeted for supporting Bengali nationalism.

But whereas these forms of anti-intellectualism were emerging from established political forces from both the left and the right, according to the American historian of science Michael Shermer, a more curious idea of anti-intellectualism began to develop within Western academia.

In the September 1, 2017 issue of Scientific American, Shermer writes that this was because ‘postmodernism’ had begun to ‘hijack’ various academic disciplines in the 1990s.

Postmodernism emerged in the 20th century as a critique of modernism. It derided modernism as a destructive force that had used its ideas of secularism, democracy, economic progress, science and reason as tools of subjugation. Shermer writes that, by the 1990s, postmodernism was positing that there was no objective truth and that science and empirical facts are tools of oppression. This is when even the celebrated leftist intellectual Noam Chomsky began to warn that postmodernism had turned anti-science.

‘Post-colonialism’ or the critique of the remnants of Western colonialism was very much a product of postmodernism as well. Oliver Lovesey in his book The Postcolonial Intellectual and the historian Arif Dirlik in the 1994 issue of The Critical Inquiry, take to task post-colonialism as a discipline now populated by non-white groups of academics who found themselves in positions of privilege in Western universities.

Lovesey quotes the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek as saying, “Post-colonialism is the invention of some rich guys from India who saw that they could make a good career in top Western universities by playing on the guilt of white liberals.”

Imran Khan is a classic example of how postmodernism and post-colonialism have become cynical anti-intellectual pursuits. Khan often reminds us that social and economic progress should not be undertaken to please the West because that smacks of a colonial mindset.

So, as his regime presides over a nosediving economy and severe political polarisation, the PM was recently reported (in the January 22 issue of The Friday Times) as discussing with his ministers whether he should mandate the wearing of the dupatta by all women TV anchors. Go figure.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 7 February 2021

Saturday, 6 February 2021

The parable of John Rawls

Janan Ganesh in The FT

In the latest Pixar film, Soul, every human life starts out as a blank slate in a cosmic holding pen. Not until clerks ascribe personalities and vocations does the corporeal world open. As all souls are at their mercy, there is fairness of a kind. There is also chilling caprice. And so Pixar cuts the stakes by ensuring that each endowment is benign. No one ends up with dire impairments or unmarketable talents in the “Great Before”.

Kind as he was (a wry Isaiah Berlin, it is said, likened him to Christ), John Rawls would have deplored the cop-out. This year is the 50th anniversary of the most important tract of political thought in the last century or so. To tweak the old line about Plato, much subsequent work in the field amounts to footnotes to A Theory of Justice. Only some of this has to do with its conclusions. The method that yielded them was nearly as vivid.

Rawls asked us to picture the world we should like to enter if we had no warning of our talents. Nor, either, of our looks, sex, parents or even tastes. Don this “veil of ignorance”, he said, and we would maximise the lot of the worst-off, lest that turned out to be us. As we brave our birth into the unknown, it is not the average outcome that troubles us.

From there, he drew principles. A person’s liberties, which should go as far as is consistent with those of others, can’t be infringed. This is true even if the general welfare demands it. As for material things, inequality is only allowed insofar as it lifts the absolute level of the poorest. Some extra reward for the hyper-productive: yes. Flash-trading or Lionel Messi’s leaked contract: a vast no. Each of these rules puts a floor — civic and economic — under all humans.

True, the phrase-making helped (“the perspective of eternity”). So did the timing: 1971 was the Keynesian Eden, before Opec grew less obliging. But it was the depth and novelty of Rawls’s thought that brought him reluctant stardom.

Even those who denied that he had “won” allowed that he dominated. Utilitarians, once-ascendant in their stress on the general, said he made a God of the individual. The right, sure that they would act differently under the veil, asked if this shy scholar had ever met a gambler. But he was their reference point. And others’ too. A Theory might be the densest book to have sold an alleged 300,000 copies in the US alone. It triumphed.

And it failed. Soon after it was published, the course of the west turned right. The position of the worst-off receded as a test of the good society. Robert Nozick, Rawls’s libertarian Harvard peer, seemed the more relevant theorist. It was a neoliberal world that saw both men out in 2002.

An un-public intellectual, Rawls never let on whether he cared. Revisions to his theory, and their forewords, suggest a man under siege, but from academic quibbles not earthly events. For a reader, the joy of the book is in tracking a first-class mind as it husbands a thought from conception to expression. Presumably that, not averting Reaganism, was the author’s aim too.

And still the arc of his life captures a familiar theme. It is the ubiquity of disappointment — even, or especially, among the highest achievers. Precisely because they are capable of so much, some measure of frustration is their destiny. I think of Tony Blair, thrice-elected and still, post-Brexit, somehow defeated. (Sunset Boulevard, so good on faded actors, should be about ex-politicians.) Or of friends who have made fortunes but sense, and mind, that no one esteems or much cares about business.

The writer Blake Bailey tells an arresting story about Gore Vidal. The Sage of Amalfi was successful across all literary forms save poetry. He was rich enough to command one of the grandest residential views on Earth. If he hadn’t convinced Americans to ditch their empire or elect him to office, these were hardly disgraces. On that Tyrrhenian terrace, though, when a friend asked what more he could want, he said he wanted “200 million people” to “change their minds”. At some level, however mild his soul, so must have Rawls.

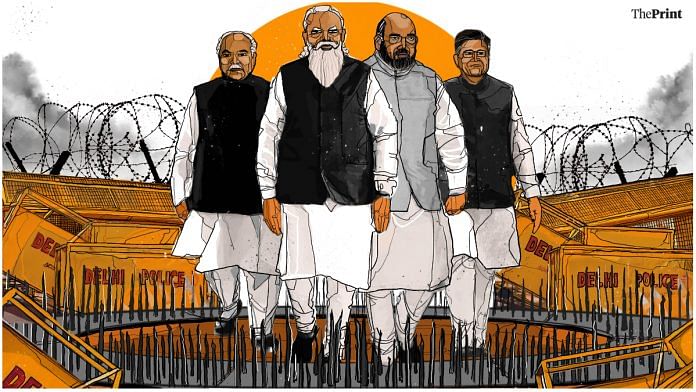

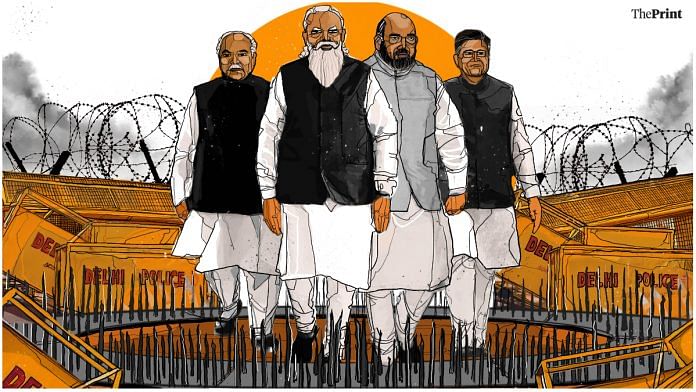

Modi govt has lost farm laws battle, now raising Sikh separatist bogey will be a grave error

Shekhar Gupta in The Print

Protests over the three farm reform laws are well into the third month now. There are six key facts, or facts as we see them, that we can list here:

1. The farm laws, by and large, are good for the farmers and India. At various points of time, most major political parties and leaders have wanted these changes. However, many of you might still disagree. But then, this is an opinion piece. I explained it in detail in this, Episode 571 of #CutTheClutter.

2. Whether the laws are good or bad for the farmer no longer matters. In a democracy, all that matters is what people affected by a policy change believe — in this case, the farmers of the northern states. Facts don’t matter if you’ve failed to convince them.

3. The Modi government is right when it says this is no longer about the farm laws. Because nobody is talking about MSP, subsidies, mandis and so on. Then what’s it about?

4. The short answer is, it is about politics. And why not? There is no democracy without politics. When the UPA was in power, the BJP opposed all its good ideas, from the India-US nuclear deal to FDI in insurance and pension. Now it’s implementing the same policies at the rate of, say, 6X.

5. As far as the farm laws are concerned, the Modi government has already lost the battle. Again, you can disagree. But this is my opinion. And I will make my case.

6. Finally, the Modi government has two choices. It can let it fester, expand into a larger political war. Or it can cut its losses and, as the Americans say, get off the kerb.

Here is the evidence that lets us say that the Modi government has lost the battle for these farm laws.

Protests over the three farm reform laws are well into the third month now. There are six key facts, or facts as we see them, that we can list here:

1. The farm laws, by and large, are good for the farmers and India. At various points of time, most major political parties and leaders have wanted these changes. However, many of you might still disagree. But then, this is an opinion piece. I explained it in detail in this, Episode 571 of #CutTheClutter.

2. Whether the laws are good or bad for the farmer no longer matters. In a democracy, all that matters is what people affected by a policy change believe — in this case, the farmers of the northern states. Facts don’t matter if you’ve failed to convince them.

3. The Modi government is right when it says this is no longer about the farm laws. Because nobody is talking about MSP, subsidies, mandis and so on. Then what’s it about?

4. The short answer is, it is about politics. And why not? There is no democracy without politics. When the UPA was in power, the BJP opposed all its good ideas, from the India-US nuclear deal to FDI in insurance and pension. Now it’s implementing the same policies at the rate of, say, 6X.

5. As far as the farm laws are concerned, the Modi government has already lost the battle. Again, you can disagree. But this is my opinion. And I will make my case.

6. Finally, the Modi government has two choices. It can let it fester, expand into a larger political war. Or it can cut its losses and, as the Americans say, get off the kerb.

Here is the evidence that lets us say that the Modi government has lost the battle for these farm laws.

First of all, there is the unilateral offer of an 18-month deferral to implementing the laws. Count 18 months from now, you will be left with only another 18 before the 2024 general elections.

You see even a Modi-Shah BJP is unlikely to risk reopening this front at that point. In fact, the bellwether heartland state elections, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, will be exactly 12 months away. Two of them have strong Congress incumbents and in the third, the BJP has bought and stolen power. Nobody’s risking losing these to make their point over farm reforms. These laws, then, are as bad as dead in the water.

Again, unilaterally, the government has already made a commitment of continuing with Minimum Support Price (MSP), although there is nothing in the laws saying it will be taken away. With so much already given away, the battle over the farm laws is lost.

The Modi government’s challenge now is to buy normalcy without making it look like a defeat. We know that it got away with one such, with the new land acquisition law. But that issue was still confined to Parliament. This is on the streets, highway choke-points, and in the expanse of wheat and paddy all around Delhi. This can spread. If the government retreats in surrender, this issue may close, but politics will rage. And why not? What is democracy but competitive politics, brutal, fair and fun? The next targets will then be other reform measures, from the new labour laws to the public listing of LIC.

What are the errors, or blunders, that brought India’s most powerful government in 35 years here? I shall list five:

1. Bringing in these laws through the ordinance route was a blunder. I speak from 20/20 hindsight, but then I am a commentator, not a political leader. To usher in the promise of sweeping change affecting the lives of more than half a billion people, the correct way would have been to market the ideas first. We don’t know if Narendra Modi now regrets not having prepared the ground for it. But the fact is, people at the mass level would be suspicious of such change through ordinances. Especially if you aren’t talking to them.

2. The manner in which the laws were pushed through Rajya Sabha added to these suspicions. This needed better parliamentary craft than the blunt use of vocal chords. This helped fan the fire, or spread the ‘hawa’ that something terrible was being forced down the surplus-producing farmers’ throats.

3. The party was riding far too high on its majority to care about allies and friends. If it had taken them along respectfully, the passage through Rajya Sabha wouldn’t have been so ungainly. At least the Akalis should never have been lost. But, as we’ve said before, this BJP does not understand Punjab or the Sikhs.

4. It also underestimated the frustration among the Jats of Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh, disempowered by the Modi-Shah politics. The senior-most Jat leaders in the Modi council of ministers are both inconsequential ministers of state. One is from distant Barmer in Rajasthan. The most visible of them, Sanjeev Balyan, won from Muzaffarnagar, where the big pro-Tikait mahapanchayat was held. In Haryana, the BJP has no Jat who counts. On the contrary, it found the marginalisation of Jat power as its big achievement. It refused to learn even from statewide, violent Jat agitations for reservations. The anger then was rooted in political marginalisation, as it is now. Ask why the BJP’s Jat ally Dushyant Chautala, or any of its Jat MPs/MLAs in UP, especially Balyan, are not on the ground, marketing these reforms? They wouldn’t dare.

5. The BJP conceded too much, too soon, unilaterally in the negotiations. It doesn’t have much more to give now. And the farm leaders have conceded nothing.

In conclusion, where does the Modi government go from here? One approach could be to tire the farmers out. On all evidence, that is not about to happen. Rabi harvest in April is still nearly 75 days away, and with much work done by mechanical harvesters and migrant workers, families would be quite capable of keeping the pickets full.

The next expectation would be that the Jats would ultimately make a deal. This is plausible. Note the key difference between Singhu and Ghazipur. In the first, no politician can even go for a selfie. Ask Ravneet Singh Bittu of the Congress, who was turned out unceremoniously. But everybody can go to Ghazipur and be photographed hugging Tikait. The Congress, Left, RLD, RJD, AAP, all of them. Even Sukhbir Singh Badal comes to Ghazipur, instead of Singhu to meet his fellow Sikhs from Punjab. Wherever there is politics and politicians, conflict resolution is possible. But what happens if this becomes a reality?

This will leave India and the Modi government with the most dangerous outcome of all. It will corner the Sikhs of Punjab. Already, the lousy barricading visuals and government’s prickly response to something as trivial as some celebrity tweets is threatening to redefine the issue from farm laws to national unity. The Modi government will err gravely if it changes the headline from farm protests to Sikh separatism.

This crisis requires political sophistication and governance skills. This BJP has neither. It has, instead, political skills and governance by clout, riding an all-conquering election-winning machine. It is the party’s inability to accept the realities of Indian politics and appreciate the limitations of a parliamentary majority that brought it here.

Does it have the smarts and sagacity to negotiate its way out of it? We can’t say. But we hope it does. Because the last thing India needs is to start another war for national unity. You would be nuts to reopen an issue in Punjab we all closed and buried by 1993.

You see even a Modi-Shah BJP is unlikely to risk reopening this front at that point. In fact, the bellwether heartland state elections, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, will be exactly 12 months away. Two of them have strong Congress incumbents and in the third, the BJP has bought and stolen power. Nobody’s risking losing these to make their point over farm reforms. These laws, then, are as bad as dead in the water.

Again, unilaterally, the government has already made a commitment of continuing with Minimum Support Price (MSP), although there is nothing in the laws saying it will be taken away. With so much already given away, the battle over the farm laws is lost.

The Modi government’s challenge now is to buy normalcy without making it look like a defeat. We know that it got away with one such, with the new land acquisition law. But that issue was still confined to Parliament. This is on the streets, highway choke-points, and in the expanse of wheat and paddy all around Delhi. This can spread. If the government retreats in surrender, this issue may close, but politics will rage. And why not? What is democracy but competitive politics, brutal, fair and fun? The next targets will then be other reform measures, from the new labour laws to the public listing of LIC.

What are the errors, or blunders, that brought India’s most powerful government in 35 years here? I shall list five:

1. Bringing in these laws through the ordinance route was a blunder. I speak from 20/20 hindsight, but then I am a commentator, not a political leader. To usher in the promise of sweeping change affecting the lives of more than half a billion people, the correct way would have been to market the ideas first. We don’t know if Narendra Modi now regrets not having prepared the ground for it. But the fact is, people at the mass level would be suspicious of such change through ordinances. Especially if you aren’t talking to them.

2. The manner in which the laws were pushed through Rajya Sabha added to these suspicions. This needed better parliamentary craft than the blunt use of vocal chords. This helped fan the fire, or spread the ‘hawa’ that something terrible was being forced down the surplus-producing farmers’ throats.

3. The party was riding far too high on its majority to care about allies and friends. If it had taken them along respectfully, the passage through Rajya Sabha wouldn’t have been so ungainly. At least the Akalis should never have been lost. But, as we’ve said before, this BJP does not understand Punjab or the Sikhs.

4. It also underestimated the frustration among the Jats of Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh, disempowered by the Modi-Shah politics. The senior-most Jat leaders in the Modi council of ministers are both inconsequential ministers of state. One is from distant Barmer in Rajasthan. The most visible of them, Sanjeev Balyan, won from Muzaffarnagar, where the big pro-Tikait mahapanchayat was held. In Haryana, the BJP has no Jat who counts. On the contrary, it found the marginalisation of Jat power as its big achievement. It refused to learn even from statewide, violent Jat agitations for reservations. The anger then was rooted in political marginalisation, as it is now. Ask why the BJP’s Jat ally Dushyant Chautala, or any of its Jat MPs/MLAs in UP, especially Balyan, are not on the ground, marketing these reforms? They wouldn’t dare.

5. The BJP conceded too much, too soon, unilaterally in the negotiations. It doesn’t have much more to give now. And the farm leaders have conceded nothing.

In conclusion, where does the Modi government go from here? One approach could be to tire the farmers out. On all evidence, that is not about to happen. Rabi harvest in April is still nearly 75 days away, and with much work done by mechanical harvesters and migrant workers, families would be quite capable of keeping the pickets full.

The next expectation would be that the Jats would ultimately make a deal. This is plausible. Note the key difference between Singhu and Ghazipur. In the first, no politician can even go for a selfie. Ask Ravneet Singh Bittu of the Congress, who was turned out unceremoniously. But everybody can go to Ghazipur and be photographed hugging Tikait. The Congress, Left, RLD, RJD, AAP, all of them. Even Sukhbir Singh Badal comes to Ghazipur, instead of Singhu to meet his fellow Sikhs from Punjab. Wherever there is politics and politicians, conflict resolution is possible. But what happens if this becomes a reality?

This will leave India and the Modi government with the most dangerous outcome of all. It will corner the Sikhs of Punjab. Already, the lousy barricading visuals and government’s prickly response to something as trivial as some celebrity tweets is threatening to redefine the issue from farm laws to national unity. The Modi government will err gravely if it changes the headline from farm protests to Sikh separatism.

This crisis requires political sophistication and governance skills. This BJP has neither. It has, instead, political skills and governance by clout, riding an all-conquering election-winning machine. It is the party’s inability to accept the realities of Indian politics and appreciate the limitations of a parliamentary majority that brought it here.

Does it have the smarts and sagacity to negotiate its way out of it? We can’t say. But we hope it does. Because the last thing India needs is to start another war for national unity. You would be nuts to reopen an issue in Punjab we all closed and buried by 1993.

Thursday, 4 February 2021

Wednesday, 3 February 2021

Monday, 1 February 2021

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)