'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 23 April 2017

Saturday, 22 April 2017

How to overcome the Master Slave Dialectic in Capitalism

Prof. Wolff on Hegel's Master-Slave Dialectic

Pakistan's Panamagate - I told you so!

Irfan Husain in The Dawn

IN a nation of some 200 million, I doubt if a handful could pinpoint Panama’s location. And yet, this tiny Central American state has dominated Pakistan’s political discourse for the last year to the point of tedium.

Finally, after nearly two months of hearings before a Supreme Court bench, the verdict is here. And, as I had predicted to friends a few weeks ago, it is a cop-out that has both sides declaring victory.

For me, the abiding image is of the Sharif brothers, Nawaz and Shahbaz, embracing and beaming at each other. In the PTI camp, we watched Imran Khan and senior party members pass sweetmeats around.

For the SC, the verdict gave the impression of balance and fairness, with something for both sides to cheer about. Imran Khan had a lot of praise for the two dissenting judges who declared the prime minister ineligible to rule because he didn’t meet the criteria of honesty and integrity laid down in the Constitution.

The ruling PML-N is gloating over a verdict that, for the time being, has let their leader off the hook. As far as the party is concerned, it has every chance of hanging on to power until the 2018 election. Here, according to opinion polls, it is most likely to win a majority. So who’s the real winner in the verdict?

When the Panama brouhaha began a year ago, I had suggested that the Sharif brothers were masters of kicking the can down the road, and would drag matters out indefinitely. Now, with a joint investigative team (JIT) being set up, expect more of the same.

Even though the SC has required the JIT to submit fortnightly progress reports, the fact remains that members of this committee will all be serving members of the civil and military bureaucracy. To expect them all to perform their tasks independently is a rather big ask.

Then there is the problem of the team having to obtain and verify information in different jurisdictions. Will they be able to force banks and government departments in Dubai and Qatar to hand over documents? And all this in two months? Forgive my scepticism, but having first-hand knowledge of the pace at which our bureaucracy works, I have some doubts.

No wonder that Imran Khan is demanding the PM’s resignation. He knows how difficult it will be to get a group of civil servants to report against a sitting PM. But he’s right in underlining Nawaz Sharif’s loss of moral authority to rule.

Irrespective of the legal rights and wrongs of the case, it is clear that the daily drip-drip-drip of corrosive evidence against Sharif and his family has done much to strip away the aura of decency he had tried to project. And his disqualification by the two dissenting judges on the bench has reinforced the impression of corrupt practices at the heart of the Sharif empire.

With supreme irony, Asif Zardari has also demanded Nawaz Sharif’s resignation, and asked if he would be taken to the local police station for questioning, or would the JIT go the PM House? The reference here was to his own vicious treatment over a decade of incarceration.

Indeed, the PPP has good reason to be aggrieved at what has often appeared to be its targeting by the judiciary, starting with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s judicial murder to the sacking of another elected PM, Yousuf Raza Gilani. In many other cases, the judiciary has displayed an apparent animus against the PPP.

And yet, despite demands for his resignation from the opposition, Nawaz Sharif isn’t going anywhere. He didn’t get to where he is by being sensitive to corruption charges. Throughout his political career, he has shown himself to be tough and opportunistic.

Imran Khan has given examples from other countries where leaders tainted by the Panama Papers have either provided full disclosure (David Cameron), or resigned (Iceland’s Sigmundur Gunnlaugsson). However, members of Putin’s and Bashar al-Assad’s inner circle have not even bothered denying the allegations against them contained in the leaks.

As we know, there is no tradition of resignations in Pakistan. Even in Israel, Bibi Netanyahu is mired in corruption charges, but is refusing to step down. But in Israel, the police are far more independent than they are in Pakistan, and have investigated similar charges against presidents and prime ministers before.

Whatever happens next, Panama is a name that will continue to resound on our TV chat shows for some time to come. But will the verdict reduce corruption? I doubt it. But it will force crooked politicians to be more careful about their bookkeeping.

A final factoid: the verdict triggered our stock exchange’s biggest bull run, with the index shooting up by 1,800 points in a single session. Do investors know something we don’t?

----The background of the case to those who don't know by Husain Haqqani

Pakistan’s Supreme Court is an arena for politics, not an avenue for resolution of legal disputes. Unlike other countries where the apex court serves as the court of last appeal, Pakistan’s Supreme Court often entertains direct applications from political actors and generates high-profile media noise. In that tradition its judgment in the so-called Panama Papers case is a classic political balancing act. It raises questions about Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s property in London, but does not remove him from office.

Opposition politician Imran Khan, currently a favourite of Pakistan’s establishment, initiated the case after Mr. Sharif’s name appeared in leaked documents about owners of offshore companies worldwide. The documents indicated that the Sharif family had borrowed money against four flats they own in London’s posh Mayfair district.

Show them the money

Having an offshore account is not in itself a violation of Pakistani law, but transferring money from Pakistan illegally is. Hence the case decided on Thursday revolved around the provenance of the money with which the Sharifs became owners of the property in London. In hearings that began in January, the petitioners insisted that the Sharif family’s ownership of this particular property could not have been possible without their possession of undeclared wealth or illegal transfers of money from Pakistan.

Instead of insisting on the time-honoured principle that accusers must prove their allegation beyond a shadow of a doubt and that investigations must precede judicial hearings, the Supreme Court acted politically. It asked the Sharifs to explain the source of money used to buy property abroad, forcing the Sharif family’s lawyers to offer various (sometimes contradictory) explanations at sensational hearings.

One of these explanations comprised a letter from a member of the Qatari royal family who said that he had transferred $8 million to the Sharif family as return on investments made in cash by the Prime Minister’s deceased father, Mian Muhammad Sharif, in the Qatari family’s real estate business in 1980.

The Qatar letter did not settle the matter because the Sharif family members had, at different times, given different explanations for the source of their funds. Moreover, the timelines of the acquisition of the London properties, the formation of the offshore company that was used to buy them and the apparent cash dealings in Qatar did not always align. In any case, a Qatari royal might be willing to send a letter for his friends, the Sharifs, but could not be expected to testify in person in Pakistan and submit himself to cross-examination, something that would be needed if the case ever went to proper trial.

The Supreme Court’s final verdict was split 3-2 among the five-judge bench, with two ruling that Prime Minister Sharif should be disqualified from holding office for failing to explain the source of money for his property. The majority said there was insufficient evidence for such a drastic step and instead announced the formation of a Joint Investigation Team (JIT) comprising five members.

These would include appointees from the Federal Investigation Agency, the National Accountability Bureau, the State Bank of Pakistan, the Securities & Exchange Commission of Pakistan and one representative each from the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and Military Intelligence (MI).

The fallout

The Prime Minister’s side breathed a sigh of relief that the court did not disqualify him from holding office, a decision it has given in the past for the removal of elected civilian Prime Ministers. Imran Khan, who wanted disqualification, declared victory even with the JIT’s creation. He and other opponents of the government are hoping that Nawaz Sharif will now bleed politically from the thousand cuts that are likely to be inflicted on him through reports emanating from the JIT.

Mr. Sharif has won elections before notwithstanding allegations of personal financial wrongdoing, but a new wave of charges could make things difficult for him in Punjab’s urban centres when Pakistan goes to the polls in 2018.

Ironically, the Supreme Court’s nearly 549-page judgment begins not by invoking some eminent jurist, but with a reference to Mario Puzo’s novel The Godfather, citing Balzac’s well-known words, “Behind every great fortune there is a crime.” But then most Pakistanis, including judges and military officers, have known for years that the fortunes of Pakistan’s uber-wealthy families come from bending or breaking laws or using political connections for private advantage. Why go looking into the origins of wealth now?

The creation of the JIT, and including two military intelligence service members who are not trained in matters relating to business and finance, says more about Pakistan’s judicial and political system than it says about the merits of this particular case. The issue in Pakistan is never corruption or failing to explain the source of funds for property. It is where someone fits into the permanent state’s scheme of things.

Nawaz Sharif was fine when he was picked up by General Zia-ul-Haq as leader of a military-backed Punjabi political elite after the coup of 1977. Courts and investigators seldom found anything wrong with the phenomenal expansion of his family’s wealth until he decided to start questioning Pakistan’s military establishment and, in recent years, even assert himself in core policy areas. Politicians can make money as long as they do not seek a role in policymaking. When Benazir Bhutto stood for a different paradigm for Pakistan, she and her husband were subjected to long-drawn legal proceedings over corruption. Asif Ali Zardari might have fewer problems on that score now after he is content to parrot the establishment’s views on national security and foreign policy. Nawaz Sharif is being put through the wringer to become more like Mr. Zardari and less like Bhutto.

As for the Pakistani Supreme Court, it intervenes to swing politics one way or another by favouring the country’s establishment against politicians or vice versa, to justify patently unconstitutional military takeovers and occasionally to embarrass one party against another. Unlike elsewhere in the world, its function is not just to determine the constitutionality and legality of judgments already given by lower courts.

As a victim of one such Commission (ironically, created on Mr. Sharif’s petition) in the so-called Memogate Case, I know that the principal damage inflicted by its proceedings is to public image. The Memogate Commission’s findings never led to criminal charges, not even an FIR, against me for any crime as none was actually committed. But its proceedings and comments created sufficient political noise for some Pakistanis to still think I am a fugitive from Pakistani law.

Signal from the deep state?

Generating smoke without fire against persons deemed difficult or uncontrollable by Pakistan’s permanent state establishment, the deep state, is often the greatest accomplishment of inquiries created by the Supreme Court on direct petitions like the one over the Panama Papers.

The JIT might still find nothing definitive for prosecution but Mr. Sharif is on notice. And that is how Pakistan’s system is designed to work.

IN a nation of some 200 million, I doubt if a handful could pinpoint Panama’s location. And yet, this tiny Central American state has dominated Pakistan’s political discourse for the last year to the point of tedium.

Finally, after nearly two months of hearings before a Supreme Court bench, the verdict is here. And, as I had predicted to friends a few weeks ago, it is a cop-out that has both sides declaring victory.

For me, the abiding image is of the Sharif brothers, Nawaz and Shahbaz, embracing and beaming at each other. In the PTI camp, we watched Imran Khan and senior party members pass sweetmeats around.

For the SC, the verdict gave the impression of balance and fairness, with something for both sides to cheer about. Imran Khan had a lot of praise for the two dissenting judges who declared the prime minister ineligible to rule because he didn’t meet the criteria of honesty and integrity laid down in the Constitution.

The ruling PML-N is gloating over a verdict that, for the time being, has let their leader off the hook. As far as the party is concerned, it has every chance of hanging on to power until the 2018 election. Here, according to opinion polls, it is most likely to win a majority. So who’s the real winner in the verdict?

When the Panama brouhaha began a year ago, I had suggested that the Sharif brothers were masters of kicking the can down the road, and would drag matters out indefinitely. Now, with a joint investigative team (JIT) being set up, expect more of the same.

Even though the SC has required the JIT to submit fortnightly progress reports, the fact remains that members of this committee will all be serving members of the civil and military bureaucracy. To expect them all to perform their tasks independently is a rather big ask.

Then there is the problem of the team having to obtain and verify information in different jurisdictions. Will they be able to force banks and government departments in Dubai and Qatar to hand over documents? And all this in two months? Forgive my scepticism, but having first-hand knowledge of the pace at which our bureaucracy works, I have some doubts.

No wonder that Imran Khan is demanding the PM’s resignation. He knows how difficult it will be to get a group of civil servants to report against a sitting PM. But he’s right in underlining Nawaz Sharif’s loss of moral authority to rule.

Irrespective of the legal rights and wrongs of the case, it is clear that the daily drip-drip-drip of corrosive evidence against Sharif and his family has done much to strip away the aura of decency he had tried to project. And his disqualification by the two dissenting judges on the bench has reinforced the impression of corrupt practices at the heart of the Sharif empire.

With supreme irony, Asif Zardari has also demanded Nawaz Sharif’s resignation, and asked if he would be taken to the local police station for questioning, or would the JIT go the PM House? The reference here was to his own vicious treatment over a decade of incarceration.

Indeed, the PPP has good reason to be aggrieved at what has often appeared to be its targeting by the judiciary, starting with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s judicial murder to the sacking of another elected PM, Yousuf Raza Gilani. In many other cases, the judiciary has displayed an apparent animus against the PPP.

And yet, despite demands for his resignation from the opposition, Nawaz Sharif isn’t going anywhere. He didn’t get to where he is by being sensitive to corruption charges. Throughout his political career, he has shown himself to be tough and opportunistic.

Imran Khan has given examples from other countries where leaders tainted by the Panama Papers have either provided full disclosure (David Cameron), or resigned (Iceland’s Sigmundur Gunnlaugsson). However, members of Putin’s and Bashar al-Assad’s inner circle have not even bothered denying the allegations against them contained in the leaks.

As we know, there is no tradition of resignations in Pakistan. Even in Israel, Bibi Netanyahu is mired in corruption charges, but is refusing to step down. But in Israel, the police are far more independent than they are in Pakistan, and have investigated similar charges against presidents and prime ministers before.

Whatever happens next, Panama is a name that will continue to resound on our TV chat shows for some time to come. But will the verdict reduce corruption? I doubt it. But it will force crooked politicians to be more careful about their bookkeeping.

A final factoid: the verdict triggered our stock exchange’s biggest bull run, with the index shooting up by 1,800 points in a single session. Do investors know something we don’t?

----The background of the case to those who don't know by Husain Haqqani

Pakistan’s Supreme Court is an arena for politics, not an avenue for resolution of legal disputes. Unlike other countries where the apex court serves as the court of last appeal, Pakistan’s Supreme Court often entertains direct applications from political actors and generates high-profile media noise. In that tradition its judgment in the so-called Panama Papers case is a classic political balancing act. It raises questions about Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s property in London, but does not remove him from office.

Opposition politician Imran Khan, currently a favourite of Pakistan’s establishment, initiated the case after Mr. Sharif’s name appeared in leaked documents about owners of offshore companies worldwide. The documents indicated that the Sharif family had borrowed money against four flats they own in London’s posh Mayfair district.

Show them the money

Having an offshore account is not in itself a violation of Pakistani law, but transferring money from Pakistan illegally is. Hence the case decided on Thursday revolved around the provenance of the money with which the Sharifs became owners of the property in London. In hearings that began in January, the petitioners insisted that the Sharif family’s ownership of this particular property could not have been possible without their possession of undeclared wealth or illegal transfers of money from Pakistan.

Instead of insisting on the time-honoured principle that accusers must prove their allegation beyond a shadow of a doubt and that investigations must precede judicial hearings, the Supreme Court acted politically. It asked the Sharifs to explain the source of money used to buy property abroad, forcing the Sharif family’s lawyers to offer various (sometimes contradictory) explanations at sensational hearings.

One of these explanations comprised a letter from a member of the Qatari royal family who said that he had transferred $8 million to the Sharif family as return on investments made in cash by the Prime Minister’s deceased father, Mian Muhammad Sharif, in the Qatari family’s real estate business in 1980.

The Qatar letter did not settle the matter because the Sharif family members had, at different times, given different explanations for the source of their funds. Moreover, the timelines of the acquisition of the London properties, the formation of the offshore company that was used to buy them and the apparent cash dealings in Qatar did not always align. In any case, a Qatari royal might be willing to send a letter for his friends, the Sharifs, but could not be expected to testify in person in Pakistan and submit himself to cross-examination, something that would be needed if the case ever went to proper trial.

The Supreme Court’s final verdict was split 3-2 among the five-judge bench, with two ruling that Prime Minister Sharif should be disqualified from holding office for failing to explain the source of money for his property. The majority said there was insufficient evidence for such a drastic step and instead announced the formation of a Joint Investigation Team (JIT) comprising five members.

These would include appointees from the Federal Investigation Agency, the National Accountability Bureau, the State Bank of Pakistan, the Securities & Exchange Commission of Pakistan and one representative each from the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and Military Intelligence (MI).

The fallout

The Prime Minister’s side breathed a sigh of relief that the court did not disqualify him from holding office, a decision it has given in the past for the removal of elected civilian Prime Ministers. Imran Khan, who wanted disqualification, declared victory even with the JIT’s creation. He and other opponents of the government are hoping that Nawaz Sharif will now bleed politically from the thousand cuts that are likely to be inflicted on him through reports emanating from the JIT.

Mr. Sharif has won elections before notwithstanding allegations of personal financial wrongdoing, but a new wave of charges could make things difficult for him in Punjab’s urban centres when Pakistan goes to the polls in 2018.

Ironically, the Supreme Court’s nearly 549-page judgment begins not by invoking some eminent jurist, but with a reference to Mario Puzo’s novel The Godfather, citing Balzac’s well-known words, “Behind every great fortune there is a crime.” But then most Pakistanis, including judges and military officers, have known for years that the fortunes of Pakistan’s uber-wealthy families come from bending or breaking laws or using political connections for private advantage. Why go looking into the origins of wealth now?

The creation of the JIT, and including two military intelligence service members who are not trained in matters relating to business and finance, says more about Pakistan’s judicial and political system than it says about the merits of this particular case. The issue in Pakistan is never corruption or failing to explain the source of funds for property. It is where someone fits into the permanent state’s scheme of things.

Nawaz Sharif was fine when he was picked up by General Zia-ul-Haq as leader of a military-backed Punjabi political elite after the coup of 1977. Courts and investigators seldom found anything wrong with the phenomenal expansion of his family’s wealth until he decided to start questioning Pakistan’s military establishment and, in recent years, even assert himself in core policy areas. Politicians can make money as long as they do not seek a role in policymaking. When Benazir Bhutto stood for a different paradigm for Pakistan, she and her husband were subjected to long-drawn legal proceedings over corruption. Asif Ali Zardari might have fewer problems on that score now after he is content to parrot the establishment’s views on national security and foreign policy. Nawaz Sharif is being put through the wringer to become more like Mr. Zardari and less like Bhutto.

As for the Pakistani Supreme Court, it intervenes to swing politics one way or another by favouring the country’s establishment against politicians or vice versa, to justify patently unconstitutional military takeovers and occasionally to embarrass one party against another. Unlike elsewhere in the world, its function is not just to determine the constitutionality and legality of judgments already given by lower courts.

As a victim of one such Commission (ironically, created on Mr. Sharif’s petition) in the so-called Memogate Case, I know that the principal damage inflicted by its proceedings is to public image. The Memogate Commission’s findings never led to criminal charges, not even an FIR, against me for any crime as none was actually committed. But its proceedings and comments created sufficient political noise for some Pakistanis to still think I am a fugitive from Pakistani law.

Signal from the deep state?

Generating smoke without fire against persons deemed difficult or uncontrollable by Pakistan’s permanent state establishment, the deep state, is often the greatest accomplishment of inquiries created by the Supreme Court on direct petitions like the one over the Panama Papers.

The JIT might still find nothing definitive for prosecution but Mr. Sharif is on notice. And that is how Pakistan’s system is designed to work.

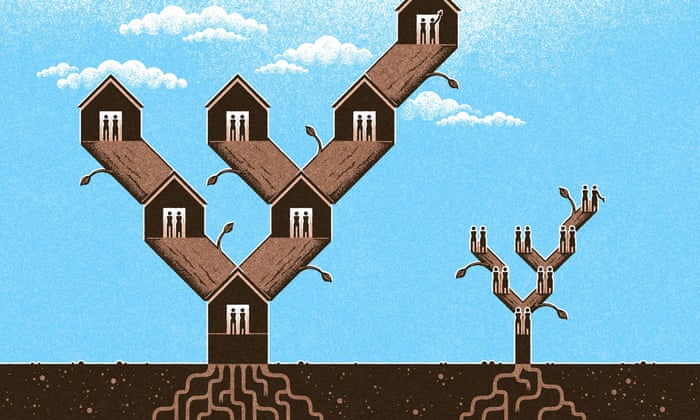

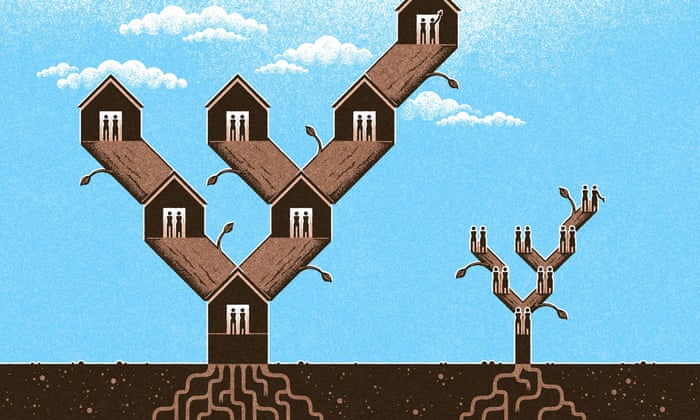

Property feeds the roots of inequality in Britain. Inheritance will entrench it

Ian Jack in The Guardian

What did our grandparents leave us? That will depend on who they were and what they possessed, but in my case, not untypical of my generation, it wasn’t very much.

From my father’s side the treasures included: a stuffed canary; a tiny stuffed crocodile (a gharial, taken from the Ganges); some crested china bought in seaside resorts; and a canteen of excellent cutlery given as a wedding present in 1899 and never taken from its box. On my grandmother’s death, a display cabinet was bought to accommodate this sudden Victorian infusion into our household, which already had a fine little portrait of Rob Roy inherited from my mother’s father, to be followed much later (after a diversion to an aunt and then a cousin) by a wall-clock and a watercolour of a street in Kirkcaldy that looked very pretty from a distance. I’m sure to have forgotten other items – for example, I’m just now remembering the 78rpm discs of Enrico Caruso and Harry Lauder – but basically that was it.

If there was money, there was very little. No property, you see. Neither side of the family had ever owned a house – and so, in terms of material changes to their children’s lives, their deaths were inconsequential. I, on the other hand, do own a house. More than that, I own a house in London. My death, and that of a million like me, will be very consequential.

According to Steve Webb, policy director of the Royal London mutual insurance company, “a wall of housing wealth [is] set to cascade through the generations in the coming years”.

A study published this week by Royal London estimates that roughly £400bn presently tied up in homes owned by people aged 65 to 85 will be handed down to their children and grandchildren. A typical estate of what the study calls this “wealth mountain” is worth between £400,000 and £500,000, to be shared out between four or five children or adult grandchildren and often to be reinvested in property.

The study is based on a YouGov survey of more than 5,600 people covering three generations: the so-called “grandparents generation” of 65- to 85-year-old homeowners; the “sandwich” generation of parents aged 45 to 64, who have living parents from whom they might expect to inherit; and a “children’s” generation of adults aged 25 to 44 who have owner-occupier parents and grandparents.

Surveys are only surveys: caveat emptor. Nevertheless, the report discovers some intriguing differences between generations. While the youngest group believes that their grandparents should spend freely to enjoy their retirement, the grandparents themselves think it right to hoard their money for their grandchildren. Many don’t wait to die. A third of those aged 75 and over had given sizeable sums of money to their grandchildren, a generation that according to the study’s calculations have received a total of £38bn from both their parents and grandparents – often, especially in London and the south-east, to spend on property. And while grandparents tend to act out of a sense of distant benevolence, parents are responding to the “pressure” exerted by their children’s predicaments. The study’s title picks up this theme: Will harassed “baby boomers” rescue Generation Rent?

Earlier this year, the Institute for Fiscal Studies published research on the growth of inheritance as a phenomenon in British life. It showed how less than 40% of the cohort born in the 1930s have received or expect to receive a bequest, while for those born in the 1970s the figure is 75%. Their benefactors are on average much richer. In 2002-3, the household wealth of people aged 80 and over averaged £160,000; 10 years later, thanks mainly to increases in home ownership and house prices, the average had risen to £230,000.

So far, the impact of inheritance on entrenching or heightening inequality has been fairly small – the average inheritance equals only 3% of the other income its recipient can expect to generate in a lifetime. But neither the Royal London nor the IFS study expects that to last. “We are entering an unprecedented era where the older generation is retiring with vast housing wealth,” says the first in its final paragraph. “That wealth is largely being preserved through retirement and will in due course find its way down through the generations. Public policy making needs to take far more account of these very substantial financial flows and perhaps focus more attention on those who are not likely to be the beneficiaries.”

In other words, we are re-entering the world of the Victorian novel, in which suitable marriages, contested wills and misplaced legacies drive the plot, while the poor – the people without lawyers – press their faces against the window of this vigorous, scheming world and merely invite our sympathy.

It wasn’t supposed to happen. “Come with us, then, towards the next decade,” said Margaret Thatcher, winding up her speech to the Conservative party conference in 1985. “Let us together set our sights on a Britain where three out of four families own their home, where owning shares is as common as having a car, where families have a degree of independence their forefathers could only dream about.”

Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago

Two years later the writer Neal Ascherson wrote a prescient column in the Observer that he recalls as “the most popular column I ever wrote … It was greedily read by the yuppie generation – and then fiercely denounced for being wrong.” Foreseeing that soaring house prices meant that London’s middle-class young would inherit many millions when their parents died, Ascherson predicted an “explosion of liquid wealth that would create instant and colossal inequality”: a society with an upper class rich enough to maintain servants, in a “court city” drained of industry that had reverted to the production of luxurious baubles.

Economists pointed out that the cash raised from property sales wouldn’t be “liquid” – it would be sucked up by the inflated cost of the new houses the inheritors moved into – but from today’s vantage point Ascherson’s futurism does not look so wrong. A new super-rich class with butlers and housemaids has moved in, though mainly from overseas rather than Britain, while owner-occupation has become a mirage for growing numbers of the less well-off.

Homeownership today stands just slightly above the rate when Thatcher made her speech: 64% of all households compared with 61% of all households in 1985, having declined from a peak of 71% in 2003. Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago, while the reverse is true of older age groups.

Private renters account for more than 20% of the housing market; in 1985 the figure was 9%. High rents rule out the kind of savings needed for a deposit on a house – with an average price in London equivalent to more than 16 times the average London salary, and 12 and 13 times the mean income of people in their 20s and 30s in prosperous cities such as Cambridge and Brighton. Meanwhile prices, which might be expected to slump amid the economic uncertainty of Brexit, have instead held reasonably steady because the fall in the value of sterling has made them more attractive to international investors.

As the IFS says, these developments mean that inherited wealth is likely to play a more important – I would say crucial – role “in determining the lifetime economic resources of younger generations, with important implications for inequality and social mobility”. What can grammar schools do – supposing they really are agents of social mobility – against this coming weight of money, which will deepen privilege like a coastal shelf? The metaphor is borrowed from Philip Larkin. “They set you up, your mum and dad. They say they mean to, and they do.” For some of us, This Be the Verse.

From my father’s side the treasures included: a stuffed canary; a tiny stuffed crocodile (a gharial, taken from the Ganges); some crested china bought in seaside resorts; and a canteen of excellent cutlery given as a wedding present in 1899 and never taken from its box. On my grandmother’s death, a display cabinet was bought to accommodate this sudden Victorian infusion into our household, which already had a fine little portrait of Rob Roy inherited from my mother’s father, to be followed much later (after a diversion to an aunt and then a cousin) by a wall-clock and a watercolour of a street in Kirkcaldy that looked very pretty from a distance. I’m sure to have forgotten other items – for example, I’m just now remembering the 78rpm discs of Enrico Caruso and Harry Lauder – but basically that was it.

If there was money, there was very little. No property, you see. Neither side of the family had ever owned a house – and so, in terms of material changes to their children’s lives, their deaths were inconsequential. I, on the other hand, do own a house. More than that, I own a house in London. My death, and that of a million like me, will be very consequential.

According to Steve Webb, policy director of the Royal London mutual insurance company, “a wall of housing wealth [is] set to cascade through the generations in the coming years”.

A study published this week by Royal London estimates that roughly £400bn presently tied up in homes owned by people aged 65 to 85 will be handed down to their children and grandchildren. A typical estate of what the study calls this “wealth mountain” is worth between £400,000 and £500,000, to be shared out between four or five children or adult grandchildren and often to be reinvested in property.

The study is based on a YouGov survey of more than 5,600 people covering three generations: the so-called “grandparents generation” of 65- to 85-year-old homeowners; the “sandwich” generation of parents aged 45 to 64, who have living parents from whom they might expect to inherit; and a “children’s” generation of adults aged 25 to 44 who have owner-occupier parents and grandparents.

Surveys are only surveys: caveat emptor. Nevertheless, the report discovers some intriguing differences between generations. While the youngest group believes that their grandparents should spend freely to enjoy their retirement, the grandparents themselves think it right to hoard their money for their grandchildren. Many don’t wait to die. A third of those aged 75 and over had given sizeable sums of money to their grandchildren, a generation that according to the study’s calculations have received a total of £38bn from both their parents and grandparents – often, especially in London and the south-east, to spend on property. And while grandparents tend to act out of a sense of distant benevolence, parents are responding to the “pressure” exerted by their children’s predicaments. The study’s title picks up this theme: Will harassed “baby boomers” rescue Generation Rent?

Earlier this year, the Institute for Fiscal Studies published research on the growth of inheritance as a phenomenon in British life. It showed how less than 40% of the cohort born in the 1930s have received or expect to receive a bequest, while for those born in the 1970s the figure is 75%. Their benefactors are on average much richer. In 2002-3, the household wealth of people aged 80 and over averaged £160,000; 10 years later, thanks mainly to increases in home ownership and house prices, the average had risen to £230,000.

So far, the impact of inheritance on entrenching or heightening inequality has been fairly small – the average inheritance equals only 3% of the other income its recipient can expect to generate in a lifetime. But neither the Royal London nor the IFS study expects that to last. “We are entering an unprecedented era where the older generation is retiring with vast housing wealth,” says the first in its final paragraph. “That wealth is largely being preserved through retirement and will in due course find its way down through the generations. Public policy making needs to take far more account of these very substantial financial flows and perhaps focus more attention on those who are not likely to be the beneficiaries.”

In other words, we are re-entering the world of the Victorian novel, in which suitable marriages, contested wills and misplaced legacies drive the plot, while the poor – the people without lawyers – press their faces against the window of this vigorous, scheming world and merely invite our sympathy.

It wasn’t supposed to happen. “Come with us, then, towards the next decade,” said Margaret Thatcher, winding up her speech to the Conservative party conference in 1985. “Let us together set our sights on a Britain where three out of four families own their home, where owning shares is as common as having a car, where families have a degree of independence their forefathers could only dream about.”

Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago

Two years later the writer Neal Ascherson wrote a prescient column in the Observer that he recalls as “the most popular column I ever wrote … It was greedily read by the yuppie generation – and then fiercely denounced for being wrong.” Foreseeing that soaring house prices meant that London’s middle-class young would inherit many millions when their parents died, Ascherson predicted an “explosion of liquid wealth that would create instant and colossal inequality”: a society with an upper class rich enough to maintain servants, in a “court city” drained of industry that had reverted to the production of luxurious baubles.

Economists pointed out that the cash raised from property sales wouldn’t be “liquid” – it would be sucked up by the inflated cost of the new houses the inheritors moved into – but from today’s vantage point Ascherson’s futurism does not look so wrong. A new super-rich class with butlers and housemaids has moved in, though mainly from overseas rather than Britain, while owner-occupation has become a mirage for growing numbers of the less well-off.

Homeownership today stands just slightly above the rate when Thatcher made her speech: 64% of all households compared with 61% of all households in 1985, having declined from a peak of 71% in 2003. Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago, while the reverse is true of older age groups.

Private renters account for more than 20% of the housing market; in 1985 the figure was 9%. High rents rule out the kind of savings needed for a deposit on a house – with an average price in London equivalent to more than 16 times the average London salary, and 12 and 13 times the mean income of people in their 20s and 30s in prosperous cities such as Cambridge and Brighton. Meanwhile prices, which might be expected to slump amid the economic uncertainty of Brexit, have instead held reasonably steady because the fall in the value of sterling has made them more attractive to international investors.

As the IFS says, these developments mean that inherited wealth is likely to play a more important – I would say crucial – role “in determining the lifetime economic resources of younger generations, with important implications for inequality and social mobility”. What can grammar schools do – supposing they really are agents of social mobility – against this coming weight of money, which will deepen privilege like a coastal shelf? The metaphor is borrowed from Philip Larkin. “They set you up, your mum and dad. They say they mean to, and they do.” For some of us, This Be the Verse.

Friday, 21 April 2017

Why I want to see private schools abolished

Tim Lott in The Guardian

I am inclined towards equality of opportunity for all children. I am also aware that such a phrase is open to multiple definitions – and with most of them, such equality verges on the impossible. For instance, we can all hold up our hands in pious disapproval at the unfairness of, say, familial nepotism – such as that seen among Donald Trump’s brood – yet most of us are not much better. Anyone who is educated, or from a middle-class background is also operating on a manifestly unequal playing field.

This is largely because of the workings of social capital – of which nepotism is simply an extreme example. At a mundane level, it means having parents who are educated, interested in education, connected within the professions and happy to use those connections – what you might call cultural nepotism. I am not innocent of this. Conscience takes a fall when one’s children are involved.

This kind of inequality is difficult to legislate against. The divide between rich and poor families is growing, and largely inescapable. A new report from the Institute for Public Policy Research thinktank shows that the number of internships has risen 50% since 2010 – another leg-up for those who can afford to take low-paid or unpaid positions.

Add in decent housing, good nutrition and the imparting of confidence and the middle classes have a huge advantage, even before you talk about schooling. There are other ineradicable forms of inequality – genetic capital for instance, since intelligence, is, according to most scientific sources, at least 50% hereditary. But social capital is the most visible.

Middle-class kids will, on aggregate, still come out on top because of their pre-existing advantages

This entrenched and inevitable advantage is, perversely, why I oppose private schools far more firmly than grammar schools (which, at least in theory, could be meritocratic). It is not that I hope to take away from privileged children any unfair head start. I just want to take away the only advantage that is purely down to money and entirely subject to legislation.

Private schools add insult to injury. If you get rid of them and shift all the pupils into the state system, nothing will guarantee the latter’s improvement with more certainty. And the middle-class kids will, on aggregate, still come out on top because of their pre-existing advantages – so it is especially egregious that so many people so staunchly oppose their abolition.

Grammar schools, as envisaged in the 1944 Education Act (with selection based not solely on tests but also on aptitude and past performance) might be the answer to those who suggest the abolition of private schools would result in “dumbing down” – as long as they were a resource for the clever and motivated rather than the privileged and tutored. There would still be inequality, but it would be minimised. Absolutely level playing fields are, and always will be, a myth. However, we can make the fields less ridiculously skewed than they are at the moment.

It is doable, practically. Shame that it just appears impossible to do politically. The fact that Jeremy Corbyn is suggesting charging private schools VAT is a step in the right direction. A few more steps in that direction and he might establish a policy that would make me vote for him.

But I’ll take a (state-educated) guess that it won’t happen. There are too many people with too many fingers in the private-schooling pie – among them a fair number of Corbyn’s shadow cabinet. Because when those who stand against inequality simultaneously take advantage of it, their motivation is sorely undermined – whether or not it would be a vote winner.

Such is the insidiousness of educational inequality – so long as it works for the policy-makers themselves, it has little or no chance of real reform. Those responsible can always tell themselves that it’s just for their children’s sake. It is understandable. It may even be forgivable. But it is a total cop-out.

I am inclined towards equality of opportunity for all children. I am also aware that such a phrase is open to multiple definitions – and with most of them, such equality verges on the impossible. For instance, we can all hold up our hands in pious disapproval at the unfairness of, say, familial nepotism – such as that seen among Donald Trump’s brood – yet most of us are not much better. Anyone who is educated, or from a middle-class background is also operating on a manifestly unequal playing field.

This is largely because of the workings of social capital – of which nepotism is simply an extreme example. At a mundane level, it means having parents who are educated, interested in education, connected within the professions and happy to use those connections – what you might call cultural nepotism. I am not innocent of this. Conscience takes a fall when one’s children are involved.

This kind of inequality is difficult to legislate against. The divide between rich and poor families is growing, and largely inescapable. A new report from the Institute for Public Policy Research thinktank shows that the number of internships has risen 50% since 2010 – another leg-up for those who can afford to take low-paid or unpaid positions.

Add in decent housing, good nutrition and the imparting of confidence and the middle classes have a huge advantage, even before you talk about schooling. There are other ineradicable forms of inequality – genetic capital for instance, since intelligence, is, according to most scientific sources, at least 50% hereditary. But social capital is the most visible.

Middle-class kids will, on aggregate, still come out on top because of their pre-existing advantages

This entrenched and inevitable advantage is, perversely, why I oppose private schools far more firmly than grammar schools (which, at least in theory, could be meritocratic). It is not that I hope to take away from privileged children any unfair head start. I just want to take away the only advantage that is purely down to money and entirely subject to legislation.

Private schools add insult to injury. If you get rid of them and shift all the pupils into the state system, nothing will guarantee the latter’s improvement with more certainty. And the middle-class kids will, on aggregate, still come out on top because of their pre-existing advantages – so it is especially egregious that so many people so staunchly oppose their abolition.

Grammar schools, as envisaged in the 1944 Education Act (with selection based not solely on tests but also on aptitude and past performance) might be the answer to those who suggest the abolition of private schools would result in “dumbing down” – as long as they were a resource for the clever and motivated rather than the privileged and tutored. There would still be inequality, but it would be minimised. Absolutely level playing fields are, and always will be, a myth. However, we can make the fields less ridiculously skewed than they are at the moment.

It is doable, practically. Shame that it just appears impossible to do politically. The fact that Jeremy Corbyn is suggesting charging private schools VAT is a step in the right direction. A few more steps in that direction and he might establish a policy that would make me vote for him.

But I’ll take a (state-educated) guess that it won’t happen. There are too many people with too many fingers in the private-schooling pie – among them a fair number of Corbyn’s shadow cabinet. Because when those who stand against inequality simultaneously take advantage of it, their motivation is sorely undermined – whether or not it would be a vote winner.

Such is the insidiousness of educational inequality – so long as it works for the policy-makers themselves, it has little or no chance of real reform. Those responsible can always tell themselves that it’s just for their children’s sake. It is understandable. It may even be forgivable. But it is a total cop-out.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)