'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Tuesday, 14 December 2021

Friday, 10 December 2021

Spending without taxing: now we’re all guinea pigs in an endless money experiment

Today, citizens are unwitting participants in a covert policy experiment. It embraces the idea of higher government spending without the necessity of increased taxes. While modern monetary theory (MMT), the doctrine, has obvious appeal for politicians, irrespective of economic religion, the long-term consequences may prove problematic.

A state, MMT argues, finances its spending by creating money, not from taxes or borrowing. As nations cannot go bankrupt when they can print their own currency, deficits and debt don’t matter. Accordingly, governments should spend to ensure full employment, guaranteeing a job for everyone willing to work. Alternatively, though not formally part of MMT, governments can fund universal basic income (UBI) schemes, providing every individual an unconditional flat-rate payment irrespective of circumstances.

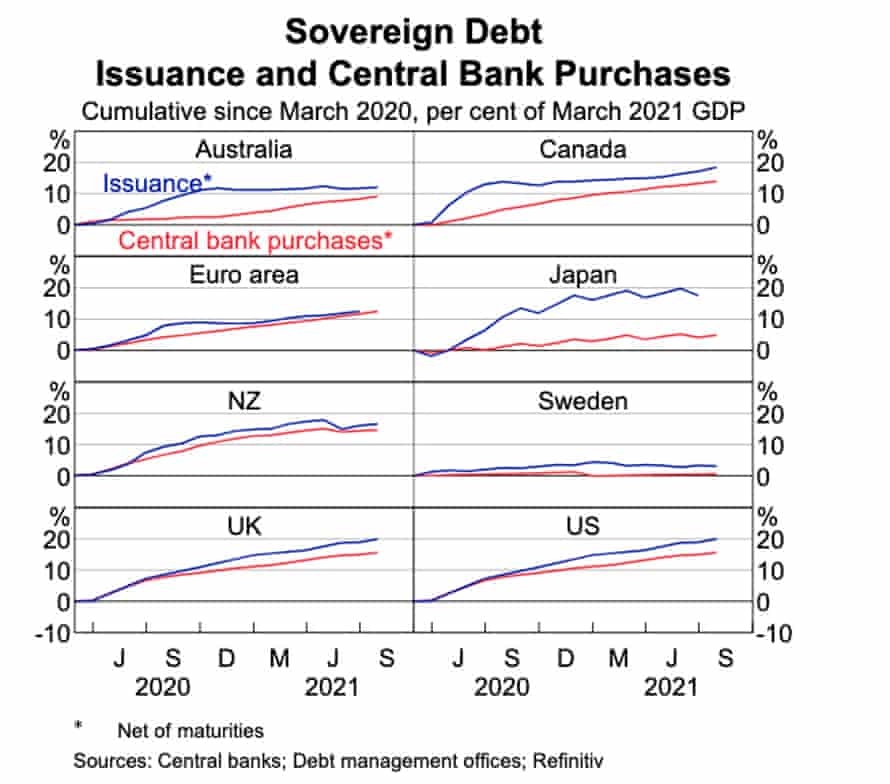

While no government or central bank overtly advocates MMT, since the 2008 global financial crisis and, more recently, the pandemic, policymakers have adopted many of its tenets by stealth. Popular one-off payments and increased welfare entitlements, which could become permanent, increasingly support economic activity. As the graph below highlights, central banks now buy a high percentage of new government debt, effectively financing this additional spending by money creation.

Source: Nick Baker, Marcus Miller and Ewan Rankin (2021 September) Government Bond Markets in Advanced Economies During the Pandemic; Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin

MMT is actually a melange of old ideas: Keynesian deficit spending; the post gold standard ability of nations to create money at will; and quantitative easing (central bank financed government spending) pioneered by Japan. However, there are several concerns about MMT.

First, the source of useful, well-compensated work is unclear. While MMT suggests taxes can be used to direct production, government influence over businesses that create jobs is limited. The impact of labour-reducing technology and competitive global supply chains is glossed over. Getting one person to dig a hole and another to fill it in creates employment, but it is of doubtful economic and social value. The woeful record of postwar centrally planned economies, where people pretended to work and the government pretended to pay them, highlights the issues.

Second, excess government spending and large deficits financed by money creation risk creating inflation. MMT argues that this is a risk only where the economy is at full employment or there is no excess capacity, and can be managed by fine-tuning intervention.

Third, MMT may weaken the currency. Roughly half of Australia’s government and significant amounts of state, bank and business debt is held by foreigners. Devaluation and loss of investor confidence in the stability of the exchange rate would affect the ability to and cost of borrowing overseas and importing goods. The expense of servicing foreign currency debt would rise.

Fourth, while available to nation states able to issue their own fiat currencies, it is unavailable to state governments, private businesses or households who are major borrowers in Australia.

Fifth, who decides the target employment rate or UBI payment level? Unemployment, inflation and output gaps are difficult to accurately measure in practice. Effects on employment incentives, workforce participation and productivity are untested. How will policymakers control the process or what would happen if MMT failed?

The theory delegates management of MMT operations to politicians, rather than unelected economic mandarins. But financially challenged elected representatives may be poorly equipped for the task. Political considerations and cronyism may influence decisions.

Sixth, there are implications for financial stability. Lower rates, the result of central bank debt purchases, and inflation fears might drive a switch to real assets, increasing the price of property and shares representing claims on underlying cashflows. It may encourage hoarding of commodities. This exacerbates inequality and increases the cost of essentials such as food, fuel and shelter. Fear of debasement of the value of paper money, in part, is behind unproductive speculation in gold and cryptocurrencies.

Seventh, MMT might undermine trust in the currency. Instead of spending the payments, citizens may question a world where governments print money and throw it out of helicopters.

Finally, Japan’s use of persistent deficits to boost short-term economic activity and incur government debt (currently more than 260% of GDP, compared with a global average of about 100%) does not prove the effectiveness of MMT. The country’s circumstances are unique and it has been mired in stagnation for three decades with its GDP largely unchanged.

MMT’s allure is the irresistible promise of freebies; full employment, unlimited higher education, healthcare and government services, state-of-the-art infrastructure, green energy and “the colonisation of Mars”. But monetary manipulation cannot change the supply of real goods and services or overcome resource constraints, otherwise prosperity and utopia would be guaranteed.

While the current game can and will continue for a time, the bill will eventually arrive. The borrowings will have to be paid for out of disposable income, higher taxes or through inflation, which reduces purchasing power, especially of the most vulnerable, and destroys savings. Other than nature’s free bounty, everything has a cost.

Thursday, 9 December 2021

Who will apologise for plasma therapy? It was a disaster for Covid-19, govt hospitals knew

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | Wikipedia

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | WikipediaThe closing pages of the 18th-century masterpiece fiction The Story of the Stone revealed the essence of the Tao’s message. In Lao Tzu’s words, it means that “Things are not as they seem, that the Eloquent may Stammer, that Perfection may seem Flawed, that Truth is Fiction, Fiction Truth.”

The truth is neither black nor white, it’s grey—the handling of the second wave of Covid-19 is a testimony to that fact.

Disaster that escaped public eye

In the midst of the second wave of Covid-19 with panic all around, a lot of therapeutic disasters were played out, and without a doubt, they were inspired by a lack of knowledge. Instead, they were fueled with a desire for one-upmanship and copycat fame. Some of the doctors unwittingly orchestrated this therapeutic mess. On one side, we had the armchair experts who were not running Covid-19 centres and had shut down their institutes. On the other, doctors in central government hospitals like the Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in Delhi were running Out Patient Departments (OPDs) and wards. They were possibly following half-baked regimens with little proof, as there were lives at stake.

While some medications were possibly harmless and cheap like Ivermectin or HCQS, the others were ridiculously expensive, and no one was wiser about their efficacy. One of them was plasma therapy. Of course, the Indian medical system and healthcare did not have the time for a randomised trial to test a placebo. But the origin of the mess was thus created right here in the capital of the country.

One may ask—who would be the expert to decide on its efficacy? The clear answer is a clinician in a hospital, handling patients with an active plasma extraction centre. But what transpired is that a centre dedicated to liver care with nil experience in Covid-19 treatment proposed the idea that plasma might help. Then came the now-famous statement of Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, saying that Delhi opened the first plasma bank in the world. That set off a chain reaction, and within a few weeks, hospitals followed suit.

It wasn’t the solution

Plasma is a component of the blood that is believed to have antibodies to diseases. Here, it was believed that Covid-19 patients would benefit from such therapy. This was when even the use of Intravenous immunoglobulin (IV IgG), a related plasma-based therapy that had been available for years, wasn’t effective in most disorders. This was also when we all knew that the so-called antibody tests of Covid-19 patients are negative or low positive. In fact, what is even more comical is that the quantity of antibodies in plasma is probably too little to do anything. And the ultimate irony is that therapy works in isolation, but here we had a plethora of medicines being administered, and it was not possible to pinpoint what was working behind the treatment.

Plasma does not come cheap, as it has to be extracted from patients. Thanks to the CM calling for plasma donation with great zeal and fanfare, the concept spread like wildfire. Intermediaries and ‘scamsters’ came in, and patients paid lakhs to get treatment, that too with dubious efficacy. Most doctors were inundated with calls for plasma, and we didn’t know what and where to arrange it for so many patients.

I know of patients who sold their belongings and went broke, partly because of plasma therapy and of course, Remdesivir, which has now been yanked off from all the guidelines. One of the members of our department, who had recovered from Covid-19, needed to give plasma to her own grandfather. He was admitted to the hospital, administered plasma but to no avail.

Trading fact for fame

Therefore, it is a must to understand the value of a placebo trial. Here, an identical-looking therapy is given to assess whether the active therapy—plasma, in this case—does anything substantial. A 30 per cent response rate is considered to be mostly placebo, or inactive, and that is the value of a placebo-controlled study.

There are numerous variables that determine the success of therapy in Covid-19, and assigning the credit to plasma showed a remarkable lack of foresight. At this juncture, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), in a multicentric study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), found that plasma wasn’t so good. But the public opinion swayed by the hospitals who pioneered the concept pilloried the paper and trashed it. Such was the distrust in our own country’s research that none wanted to get off the plasma bandwagon. Countless patients spent their life savings on what was a highly questionable therapy. And the charade continued till the second wave subsided.

The breakthrough

As always, we waited for a foreign journal to agree to a local finding, which was not surprising to a lot of us in the government hospitals. The landmark paper in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) showed that there was “No significant differences in clinical status or overall mortality between patients treated with convalescent plasma and those who received placebo.” It has been cited 455 times since it was published in February 2021. The number exceeds the citations of any of the papers published by the ‘experts’ who rolled out an untried therapy on the nation.

To add insult to injury, a section of the print media, which studiously avoided criticising them because their publications were the benefactors of full pages advertisements on plasma banks. To make it worse, some of the names suggested for the Padma awards this year included the plasma therapy pioneers.

Who takes the responsibility?

In retrospect, what needs to be asked is—who will pay for the loss of life savings and the death of patients who were given plasma therapy? Who will fill in the gaps for the distrust in medical care? Will the experts apologise? Who will apologise for pillorying the ICMR’s report that could have nipped this in the bud? But no one really apologises for such things in India.

As Donald Keough said, “The truth is, we are not that dumb and we are not that smart.” The plasma blitzkrieg was neither dumb nor smart; it was callous, and someone should be paying for the negligence today or tomorrow.

Pakistan can’t be Saudi Arabia or Iran. So it’s inching towards Talibanisation

Tragically, the dark days of General Zia’s brutality in Pakistan seem lighter today writes AYESHA SIDDIQA in The Print

A protest by Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP) supporters against the top court's verdict on Asiya Bibi

A protest by Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP) supporters against the top court's verdict on Asiya Bibi Thinking about the future of Afghanistan, especially in the last year, has been exhausting. You really begin to wonder what future are we looking at with the Taliban fairly in control of the country and the Islamic State, al-Qaeda and other militant groups present in other parts of Afghanistan. The marginally progressive, liberal and comparatively resourceful population has almost all fled the place. The scene of a State and society in tatters gnawed at my heart until I realised that socio-politically, Afghanistan is expanding into Pakistan too. While Islamabad claims the Taliban are inching towards pragmatism, Pakistan is moving towards the original formula of Talibanisation.

I am quite sure this will make the blood of many theoreticians boil, who would quickly point out that it’s flawed to mention Pakistan in the same breath as a failed country because it still has a functional bureaucracy, a strong military institution, and many systems that work. I am sure theoretical nuances wouldn’t have mattered to Priyantha Diyawadana as he was attacked and burned by a roaring crowd of Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP) supporters in Sialkot. The unfortunate man was just doing his duty as a general manager, asking the workers to clean the premises and remove all needless material from the walls that included TLP posters as the company was coming up for a foreign audit. To the jubilant young men, who took selfies with the burning body of the Sri Lankan manager, the State must have appeared like ashes to be stumped under the feet.

Those of us in Pakistan that get horrified at seeing photos of Taliban whipping women or beheading people, it would be educating to go and attend the court hearing in Sialkot to see that the average age of most suspects in the Diyawadana murder case appears to be under 30. Some will argue that though highly unfortunate, such violence happens around the world. This kind of view tends to shy from the reality that these young men (the suspects) are not just random miscreants but imagine themselves as a new force shaping up the face of the State and society. In their minds, they are taking the State in the direction that those who imagined Pakistan like Allama Iqbal, who wanted Islamic republicanism, would like — with a far heavier ideological colour than Pakistan’s national poet may have imagined. After all, didn’t the late TLP leader Khadim Rizvi constantly refer to Iqbal? This is not the story of a single murder but a natural outcome of the direction Pakistan’s identity is taking.

How religion shapes the State

I remember a conversation with renowned Pakistani scientist and activist Pervez Hoodbhoy during the 2000s when he was hopeful that the military would not let the situation get out of control and would harness the extremists it had produced to fight in Afghanistan and other fronts. Hoodbhoy imagined the military as a pragmatic and somewhat secular force. But the mistake was not only his as many policy wonks around the world had a similar view at the time– equating alcohol–consuming Generals with secularism. Many international observers also made the mistake of ignoring the fact that it was the pragmatism that would eventually kill Diyawadana and the Pakistani society along with him. The consistent use of religion to maximise power has stacked up the odds against any form of normality. Today, there is no one in Pakistan’s civil or military leadership who has the power to condemn the TLP directly. The current Army Chief, Qamar Javed Bajwa, with his controversial background is least capable of taking any action. It was Bajwa who had recently got a group of men together to negotiate a deal for the religious party to back down from its march towards Islamabad.

He was incapable of forcing his choice on the TLP mainly because he thought of the religious party as a useful tool for future purposes but also because many of his own men are tied to the ideological agenda of the issue of finality of the Prophet (Khatme Nabuwat) and blasphemy that TLP parrots. Furthermore, why forget that the TLP was trained in violence and allowed to get away with murders of police officials during their earlier protests against the Nawaz Sharif government. The army, instead of coming to the help of the civilian government, had encouraged and even participated in the violence and paid money to the TLP. In fact, the army played an instrumental role in diverting the urban trader-merchants away from the Deobandis to the Barelvis. Important to note that like the killer (Mumtaz Qadri) of former Punjab governor Salman Taseer was supported and helped by traders of Islamabad and Rawalpindi, sources said that the traders in Sialkot are providing assistance and moral help to lawyers pleading the case of those arrested in the Sri Lankan manager’s murder. In any case, the defence minister tried to downplay the violence as something ordinary.

Allama Iqbal was one leader who did not support the Khilafat movement but wanted an Islamic democracy where religious thought could be developed to shape the future of the State and society. He believed that ijma (consensus amongst religious scholars or community), which is an important source in Islamic jurisprudence, especially the principles that trickle down from companions of the Prophet, are not binding on future generations. The communal thought must be developed. The only problem with this formula was that while all efforts were made by successive Pakistani leaderships to create and emphasise the religious nature of the State, nothing was done to consciously develop the political discourse. As regimes kept developing religious institutions like the Federal Shariat Court, the Council of Islamic Ideology, the blasphemy laws, the Qisas and Diyat laws and much more, the State was allowed to keep using British laws and governance system. Every time a leader wanted to negotiate and bargain for more power, they would use religion as a tool and add to the cultural value of religion and in the process reiterate the significance of traditional ijma.

Not Iran or Saudi Arabia

Over the years, Pakistan has arrived at a point where we are neither like Saudi Arabia nor Iran. The absence of a monarchy makes it difficult for a ruler to impose a certain religious formula or change the direction of society towards less religion. More importantly, it does not have an alternative identity, which in the case of Saudi Arabia is being Arab, to fall back on to secure a sense of nationalism that does not depend on religion. Pakistan’s ruling elite consistently discouraged people from embracing multiple ethnic identities. Even Mohammad Ali Jinnah spoke about the ‘menace of provincialism’. While competing ethnic identities were discouraged, competing sectarian ideologies were encouraged. A religious State and society is the only natural direction but the problem is that, unlike Iran, Pakistan lacks a single faith. The presence of multiple competing sectarian ideologies complicates life. Thus, violence becomes a necessary tool through which various religious groups compete for greater influence. So, like the Taliban, use of force and violence will be used to impress the audience, control their imagination and maximise power.

However, there are the non-religious parties that may not compete in violence but are equally willing to use the popular religious narrative to compete politically. The issues of constituency politics has made the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI), Pakistan Muslim League–Nawaz (PML–N), or the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) all look alike as far as the religious card is concerned. They parrot the ideological position of Deobandi and now Barelvi religious gangs. Could the PPP — known as liberal and more capable than other parties to build legal/institutional mechanisms (the 18th amendment being a case in point) — provide an answer? Unfortunately, the party leadership has its limitations in the face of constituency politics as visible from its candidate in the Lahore bypolls using religion card as part of his campaign.

Religion as a negotiating and power maximising tool is used across the board – main political parties, ethnic nationalists, and even separatist movements. In Balochistan, for example, the Balochistan Nationalist Party and the Pashtunkhwa Milli Awami Party have joined hands with Maulana Fazlur Rehman to fight their battle for political survival. In another corner of the province in Gwadar, separatist leaders have instructed people to support Maulvi Hidayat-ur Rehman of Jamaat-e-Islami against the mainstream political parties or even Baloch nationalist parties that continue to subscribe to democratic principles for Baloch rights. It is heartening to hear about the progressive women marching for their rights in Gwadar. But a less talked about fact is that different mafias are aiding the maulvi, perhaps even playing to the tune of global China-US rivalry, in supporting Rehman to use the religion card for propaganda against Chinese clubs, wine factories and coastal city development in Gwadar. It is sad to see mullahs becoming the only available tool for locals to protest Chinese expansion. The fact that diverse political groups use the same tool – religion – is less a commentary about them and more a reflection on the nature of the State – it only has room for religion and religious narrative. One would have wanted it to turn into a Sunni Iran but to reiterate an earlier point, in the absence of a singular ideology it will only end up with more violence and chaos.

Tragically, the dark days of General Zia’s brutality seem lighter today. Particularly because a dissident then would land in Attock or Lahore Forts or any other State-run torture chambers. If one survived all of that, the person would get respect from society. Now, the fate of any dissident is as precarious as Diyawadana’s – the society cheers or remains silent to finish the job of the State that has almost made it a habit to feed its opponents to mob violence. It feels worse than Kabul.

Has Priti Patel stolen a leaf from BJP's playbook?

When the order was made to deprive Shamima Begum of her British citizenship in February 2019, it seemed gestural and unlikely to stand. She was born in England and had no dual nationality; her marriage to a Dutch citizen was invalid since she was 15 when she entered into it; and she had a baby, who was British by descent according to the British Nationality Act of 1981.

Within three weeks, her son had died, and the gesture had solidified into something darker and more concrete: a statement of values, in which some citizens are more British than others. What should be seen as chilling safeguarding issues – underage girls trafficked by criminal gangs into war zones – became security matters, in which the national interest is so profoundly threatened that, not only is the state relieved of its duty to protect, the girls can be made stateless.

Begum is not the only British citizen treated in this way. A recent Reprieve report details 20 British families stranded in north-east Syria, most of whom have had their citizenship removed. To divest us of any illusions, that these are freak occurrences for the monumentally unlucky, we now have the third reading of the nationality and borders bill. Forty-four members of the Scottish parliament signed an open letter to the home secretary, detailing what they considered to be its implications for asylum seekers – cruel measures to make already unsafe routes more treacherous – but noting, also, that it hangs “the threat of citizenship removal over naturalised British people in clear violation of international human rights agreements and basic principles of decency and fairness”.

Under the proposals, any foreign-born British citizen can be deprived of their citizenship, without notice or notification. Dual citizenship is not a precondition; they can be made stateless so long as the British government believes they are eligible for citizenship of another country. Analysis from the 2011 census, by the New Statesman, finds an astronomical number of people – 5.5 million in England and Wales – who fall into this category, including about 408,000 people born in the UK. It is hard to imagine a more flagrantly racist idea emanating from anywhere but a National Front manifesto: it affects half of British Asians and 39% of Black Britons.

This represents merely an acceleration of the Conservative agenda over the past decade. The Cameron years were more timid and underhand. The hostile environment policy of 2012, and the Windrush scandal it created, was openly racist, but limited in scope to one cohort. This in no way mitigated the injustice of it; to deprive one citizen of statehood, not to mention liberty, legal rights, healthcare, social security and the ability to work, is to deprive all. But it was a long time before it received due attention and protest, and victims are still waiting for restitution. That same year, the minimum income threshold of £18,600 was introduced for British citizens who wanted to bring a foreign spouse into the UK. The implications of this were, again, unremarked for a long time, but extraordinary; poor Britons thereafter had fewer rights as citizens than rich ones.

So citizenship was, from 2012, stratified by race and class. Full rights were enjoyed by a particular cross-section, and those outside it were newly precarious. Even if that insecurity were hypothetical – how many of us will, in the end, marry someone foreign born? How many are in the Windrush generation? – the principle was real, and ambient noise shored it up, not just Theresa May’s racist “Go Home” van but a fixation with shirkers and strivers, reinforcing a new conception of civic decency being a function of economic productivity.

Cameron’s government came to power, after its coalition fits and starts, on the back of a fiscal scarcity narrative that popularised austerity measures whose cruelty would have previously been unsellable. In power, the Conservatives have adjusted that scarcity so that it is no longer just money but also belonging that we don’t have enough of; there is simply not enough citizenship to go around, not enough nationhood, not enough human rights for the whole country to enjoy. Priti Patel may not need to repatriate your neighbours to nowhere today, but she needs to start knocking the legislation into shape, so that when the deportations begin, she knows who least belongs.

The question is not how likely it is that five and a half million Britons ever face deportation: it is, what political purpose does it serve to turn citizenship into a question not of unity but of hierarchy? It is more complex and intricate than simply sowing division and eroding solidarity; it generates emotional support for external xenophobia – against the EU, against refugees – by making the condition of Britishness a fragile one in which legitimacy is uncertain and loyalty must be continually demonstrated. The racism of the nationality and borders bill is not a Tory accident. It creates the conditions for their future successes and cover for their vast, unfolding errors; it’s up to all opposition parties to make sure it costs them more, electorally, than it can ever deliver.

Wednesday, 8 December 2021

Tuesday, 7 December 2021

The richest 10% produce half of greenhouse gas emissions. They should pay to fix the climate

This is not simply a rich versus poor countries divide: there are huge emitters in poor countries, and low emitters in rich countries writes Lucas Chancel in The Guardian ‘At current global emissions rates, the carbon budget that we have left if we are to stay under 1.5°C will be depleted in six years.’ Photograph: Friedemann Vogel/EPA

‘At current global emissions rates, the carbon budget that we have left if we are to stay under 1.5°C will be depleted in six years.’ Photograph: Friedemann Vogel/EPA

Let’s face it: our chances of staying under a 2C increase in global temperature are not looking good. If we continue business as usual, the world is on track to heat up by 3C at least by the end of this century. At current global emissions rates, the carbon budget that we have left if we are to stay under 1.5C will be depleted in six years. The paradox is that, globally, popular support for climate action has never been so strong. According to a recent United Nations poll, the vast majority of people around the world sees climate change as a global emergency. So, what have we got wrong so far?

There is a fundamental problem in contemporary discussion of climate policy: it rarely acknowledges inequality. Poorer households, which are low CO2 emitters, rightly anticipate that climate policies will limit their purchasing power. In return, policymakers fear a political backlash should they demand faster climate action. The problem with this vicious circle is that it has lost us a lot of time. The good news is that we can end it.

Let’s first look at the facts: 10% of the world’s population are responsible for about half of all greenhouse gas emissions, while the bottom half of the world contributes just 12% of all emissions. This is not simply a rich versus poor countries divide: there are huge emitters in poor countries, and low emitters in rich countries.

Consider the US, for instance. Every year, the poorest 50% of the US population emit about 10 tonnes of CO2 per person, while the richest 10% emit 75 tonnes per person. That is a gap of more than seven to one. Similarly, in Europe, the poorest half emits about five tonnes per person, while the richest 10% emit about 30 tonnes – a gap of six to one. (You can now view this data on the World Inequality Database.)

Where do these large inequalities come from? The rich emit more carbon through the goods and services they buy, as well as from the investments they make. Low-income groups emit carbon when they use their cars or heat their homes, but their indirect emissions – that is, the emissions from the stuff they buy and the investments they make – are significantly lower than those of the rich. The poorest half of the population barely owns any wealth, meaning that it has little or no responsibility for emissions associated with investment decisions.

Why do these inequalities matter? After all, shouldn’t we all reduce our emissions? Yes, we should, but obviously some groups will have to make a greater effort than others. Intuitively, we might think here of the big emitters, the rich, right? True, and also poorer people have less capacity to decarbonize their consumption. It follows that the rich should contribute the most to curbing emissions, and the poor be given the capacity to cope with the transition to 1.5C or 2C. Unfortunately, this is not what is happening – if anything, what is happening is closer to the opposite.

It was evident in France in 2018, when the government raised carbon taxes in a way that hit rural, low-income households particularly hard, without much affecting the consumption habits and investment portfolios of the well-off. Many families had no way to reduce their energy consumption. They had no option but to drive their cars to go to work and to pay the higher carbon tax. At the same time, the aviation fuel used by the rich to fly from Paris to the French Riviera was exempted from the tax change. Reactions to this unequal treatment eventually led to the reform being abandoned. These politics of climate action, which demand no significant effort from the rich yet hurt the poor, are not specific to any one country. Fears of job losses in certain industries are regularly used by business groups as an argument to slow climate policies.

Countries have announced plans to cut their emissions significantly by 2030 and most have established plans to reach net-zero somewhere around 2050. Let’s focus on the first milestone, the 2030 emission reduction target: according to my recent study, as expressed in per capita terms, the poorest half of the population in the US and most European countries have already reached or almost reached the target. This is not the case at all for the middle classes and the wealthy, who are well above – that is to say, behind – the target.

One way to reduce carbon inequalities is to establish individual carbon rights, similar to the schemes that some countries use to manage scarce environmental resources such as water. Such an approach would inevitably raise technical and information issues, but it is a strategy that deserves attention. There are many ways to reduce the overall emissions of a country, but the bottom line is that anything but a strictly egalitarian strategy inevitably means demanding greater climate mitigation effort from those who are already at the target level, and less from those who are well above it; this is basic arithmetic.

Arguably, any deviation from an egalitarian strategy would justify serious redistribution from the wealthy to the worse off to compensate the latter. Many countries will continue to impose carbon and energy taxes on consumption in the years to come. In these contexts, it is important that we learn from previous experiences. The French example shows what not to do. In contrast, British Columbia’s implementation of a carbon tax in 2008 was a success – even though the Canadian province relies heavily on oil and gas – because a large share of the resulting tax revenues goes to compensate low- and middle-income consumers via direct cash payments. In Indonesia, the ending of fossil fuel subsidies a few years ago meant extra resources for government but also higher energy prices for low-income families. Initially highly contested, the reform was accepted when the government decided to use the revenue to fund a universal health insurance and support to the poorest.

To accelerate the energy transition, we must also think outside the box. Consider, for example, a progressive tax on wealth, with a pollution top-up. This would accelerate the shift out of fossil fuels by making access to capital more expensive for the fossil fuel industries. It would also generate potentially large revenues for governments that they could invest in green industries and innovation. Such taxes would be politically easier to pass than a standard carbon tax, since they target a fraction of the population, not the majority. At the world level, a modest wealth tax on multimillionaires with a pollution top-up could generate 1.7% of global income. This could fund the bulk of extra investments required every year to meet climate mitigation efforts.

Whatever the path chosen by societies to accelerate the transition – and there are many potential paths – it’s time for us to acknowledge there can be no deep decarbonization without profound redistribution of income and wealth.