By the time you are reading this, Aryan Khan would be walking out of jail, if 25 days too late. Everything we know about the case as yet tells us there was nothing to justify his arrest, incarceration and being charged under such a draconian law in any case. His ordeal, however, has given us another ‘star’ of sorts, Sameer Dawood/Dnyandev Wankhede.

What kind of star — good or bad, a wronged hero or a villain who finally got caught out — you can decide. He’s a polarising figure. For some, he’s a reservation fraud who allegedly claimed a place in the quota reserved for Scheduled Castes, hiding the fact that he’s a Muslim. No problem with that, except that caste-based reservation wouldn’t be available to him. For others, he’s a Muslim and a Dalit who’s being victimised by entitled elites only because he dared to go after them.

For some, he’s a bully and probable “blackmailer” who targeted the rich and famous, especially in Bollywood, for fame, and allegedly, ransom. For others, he’s finally the one brave narc who decided to do his job , no matter how powerful his quarry.

We cannot take any side on this, and we aren’t. Because we do not have the facts. Our instinct comes from subjectivity, because that’s how we’d see the facts arrayed before us. We shall get off the kerb on this, and focus on something else. Less tangible, and not polarising. It is called propriety in government service. Especially as applied to the All India and Class I Services.

Let me ask you a trick question. How many IAS officers can you name in the country right now? Not members of your family or pals, but from the headlines, especially the recent ones? Or IPS officers? And finally, that one service we see so little of in our normal lives directly, the Indian Revenue Service, the so-called ‘taxman’ or woman.

So, is there a prominent IRS officer you can name off the bat? I bet it would be Sameer Wankhede. He’s not only the most famous IRS officer in the country today, but in a very long time. It is serendipitous that the two most headlined names from the All India Services at this point, IAS and IPS, have also not necessarily been there for good reasons.

Former Comptroller and Auditor General Vinod Rai gave a grovelling apology to Congress leader Sanjay Nirupam for making false allegations over the 2G case, where he conjured up that notional loss figure of Rs 1.76 lakh crore in 2007.

It was an obvious exaggeration. But such was the mood at that point you couldn’t argue with him without risking being labelled ‘pro-corruption’. Now that story has unravelled. As indeed, unfortunately, India’s telecom sector. The same thing happened soon enough with coal.

The IPS now. The same Mumbai which produced Wankhede, the zonal narcotics chief who now, in his own defence, is citing the testimony of the young man he charged with a crime with a possible 10-year sentence (‘see, even Aryan says he’s made no charge of extortion against me’), has also given us a police commissioner who’s absconding. All of Maharashtra Police cannot find one of its most senior officers, and non-bailable warrants are being posted everywhere.

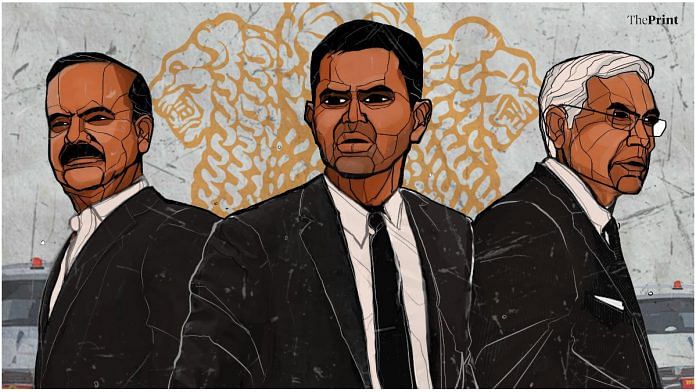

If IPS, IRS and IAS are the trinity of our vaunted civil services and Param Bir Singh, Sameer Wankhede and Vinod Rai are their representatives in today’s most prominent — and bad — headlines, what does it tell us?

We have chosen that order deliberately. The IPS guy on top because he’s an absconder, ducking multiple criminal charges; the IRS man next because he’s in court seeking protection from arrest and yet to answer a hundred questions on his conduct; and the IAS last, for once, because at least one thing we know about Vinod Rai from reputation and track record is that he is, financially, spotless. Just that it has not achieved the best results for India.

These three stars of today speak poorly for our civil services in their own different ways. It is to fight for these services that lakhs of our brightest young people slog for years at coaching academies, often making their parents sell their land and buffaloes, in that one hope: My kid will crack UPSC. Then, they walk into their respective academies with pride in their hearts, stars in their eyes and mostly — I speak from experience of having spoken at these academies and interacted with young recruits — a great deal of idealism.

No, I am not about to lapse into convenient mass condemnation. Mine has never been the ‘sab chor hain’ view. It is absolutely to the contrary, which I dared to say even during those bizarre Anna Hazare months. The point here is, for every Param Bir Singh, there are thousands of others in his service doing their jobs honestly, sincerely, and at very modest government salaries. As there must be in the IAS or the IRS. It is just that we do not know about them. It is just that people who are becoming famous have done so for all the wrong reasons.

Trick questions again: Name the last six incumbents in the office of the Cabinet Secretary, Director, Intelligence Bureau, and Chairperson of the Central Board of Direct Taxes? If you can name six of each, that is 18 who sat at the apex respectively of these three services, I’d say you are brilliant. But you know the three names in the headlines today, sadly. Or some of you might recall the name of the young IAS officer who was asking his police to ‘smash the farmers’ heads’ in Haryana, or one in Chhattisgarh bashing up a passerby on camera for ‘defying the lockdown’ and other such. Good guys go unnoticed, unsung. Tragic, because they are straight, professional, and play by the book.

Now, what is that book? Bollywood deserves our eternal gratitude because it can always make a telling point for us. People dug out this clip from that otherwise noisy nothing of a movie Tiranga (made in 1993 by Mehul Kumar), where Raj Kumar, in his characteristic, much-mimicked drawl, pulls out two papers from his pocket to confront the corrupt traitor of a police officer. These are for you, he says. One is the order of my release from jail, and the other for your arrest. The clip is being shared with the caption ‘Aryan Khan to Wankhede’.

Go to the movie on YouTube and listen to the context of that clip. What oath do you take when you join this service, don this uniform, he asks, and then reads out the oath every Indian joining all-India services mandatorily takes while joining their service: ‘I do swear/solemnly affirm that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to…the Constitution of India…that I will carry out the duties of my office loyally, honestly and with impartiality’.

We shall leave it to the conscience of these latest ‘superstars’ of the civil services to ask themselves if they’ve been true to this oath. It’s also a question many others in these services need to ask themselves, as they lock up students for sedition and UAPA only because of the cricket team they support, civil, servant, fame, or for sharing the Greta Thunberg toolkit, or trumping up charges against anybody they think the political bosses want ‘fixed.’ In 2021, they aren’t better than the notorious Soviet hatchet man of seven decades ago, Lavrentiy Beria, who offered to arrest somebody Stalin was irritated with. But under which charge, Stalin apparently asked him. You give me the man, Beria said, and I will give you the charge.

Late S.S. Khera was one of those immortal doyens of the old ICS, and so self-effacing that Google also throws up so little on him. He was India’s first Sikh Cabinet Secretary (1962-64), made his fame using tanks to stop the Partition riots in Meerut in 1947, and totally frowned at civil servants seeking fame. One mention in the newspapers, he said, is one black mark. Two, a bad ACR. And a photo should invite the sack. Now we know the times have changed in six decades. But we also see what this madness for fame and stardom has done to some people from great services. Even as most others work sincerely, in relative anonymity.