'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 9 June 2021

Monday, 7 June 2021

Benford’s Law detects data fudging. So we ran it through Indian states’ Covid numbers

DINESH SINGH and AJAY KUMAR in the Print look at the Covid data from the US, UK and several Indian states. Some very interesting insights emerge:

A healthcare worker collects sample for Covid testing. Assam has a caseload of 3.15 lakh and a total of 1,984 people have died of Covid in the state. (Representational image) | PTI

A healthcare worker collects sample for Covid testing. Assam has a caseload of 3.15 lakh and a total of 1,984 people have died of Covid in the state. (Representational image) | PTI

During this global pandemic, several nations across different geographical regions, have had the accuracy of their Covid-19 data records looked at with a healthy dose of questioning. For instance, even with the best of intentions, some western nations have had difficulties in classifying their Covid-19 data. This does not necessarily imply deliberate misrepresentation of the data on part of the agencies responsible. It is just that a pandemic that has left the world shaken in so many ways will also, doubtless, affect data keeping. At the same time, when it comes to data records, it is of utmost importance to endeavour towards maintaining accuracy to the extent possible.

In such a situation, it is useful to try and gauge the accuracy or reliability of the data through various methods. One such fairly reliable means of measuring the accuracy of numeric data sets is a simple mathematical law that was discovered many decades ago and is generally known as the Benford’s Law. This easy to state and just as easy to understand law deals with gauging the reliability or accuracy of large data sets consisting of numeric data that has occurred in natural or non-artificial ways. In other words, the data set must consist of plenty of numbers and these numbers should have arisen without deliberate interference or manipulation. It is generally accepted that the law is meaningfully applicable in instances where the number of data points is at least 500. Also, the meaning of ‘naturally occurring data’ is best understood through illustrations such as of the type related to stock markets or tax records or population data.

Benford’s Law and its application

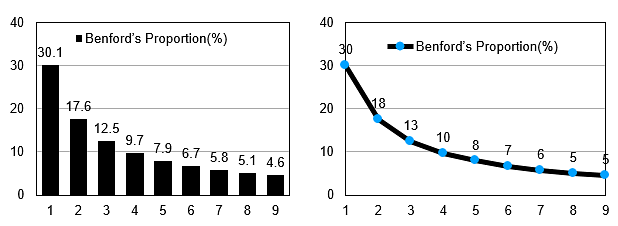

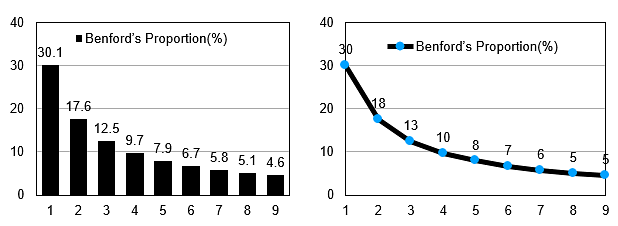

The law was discovered, actually rediscovered, by Charles Benford in 1938. To grasp this simple law, we need to understand the meaning of the term ‘leading digit’. Given any number, say 813, its leading or first digit is 8. Obviously, we can have only 9 leading digits in any combination viz. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. The law says that given a naturally arising collection of very, many numbers, the number of times each leading digit occurs as a percentage of the entire lot of leading digits is fixed. In other words, in the entire collection of leading digits arising from a naturally occurring collection of numbers associated with a phenomenon, the number 1 must occur about 30 per cent of the time; the digit 2 about 17 per cent of the time and so on in a certain decreasing order for the other 7 digits where 9 occurs 4.6 per cent of the time. Hence, if the data is true then in about 1000 numbers, 1 occurs as a leading digit about 300 times and so on. This is best illustrated through the following precisely stated table and also pictorially by the succeeding graphs.

What happens when in a given data set of leading digits, arising from numbers denoting a natural phenomenon, is not in conformity with the law? The answer is simple; there is a very high chance that the data is not reliable either because of inaccurate records or because of manipulation.

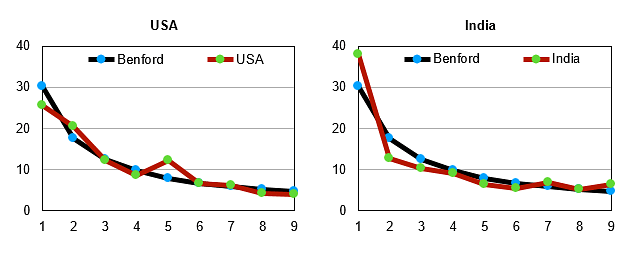

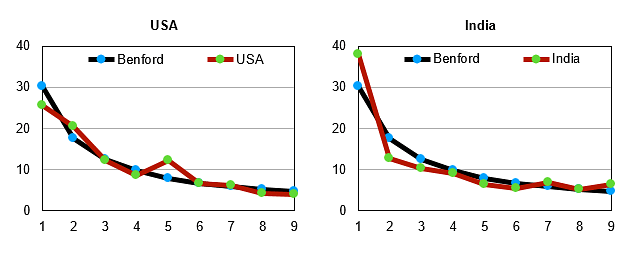

One of the best ways to contrast the actual data against that prescribed by Benford’s Law is visually, through a graph. That is precisely what we shall be doing for all figures in the article. We shall superimpose the curve given by the actual data (always in red) over the standard curve prescribed by Benford’s Law (always in black). The Benford curve shall look like a slide descending from the right to the left. The deviations of the curve representing the actual data vis a vis the Benford’s curve shall reveal unreliability of the data set.

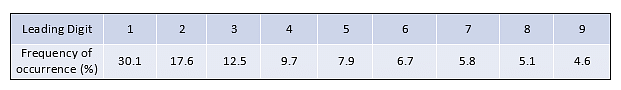

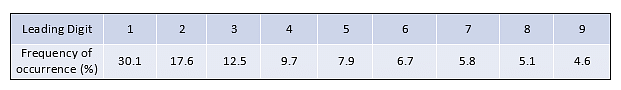

The prowess of the law is best gauged by a look at the financial data of the now defunct former energy giant Enron Corporation. It is now well known that Enron had been fudging its financial data. This can be seen in the figure below where the data curve for Enron’s revenues is a very bad fit over the Benford curve. It is actually a no brainer to infer that Enron had heavily manipulated its financial data as can be seen by the number of significant deviations of the Enron data curve from the standard Benford curve.

Testing Covid data

We have in this article attempted to look at the data arising from Covid-19 cases across countries and across several states of India. Some very interesting insights emerge.

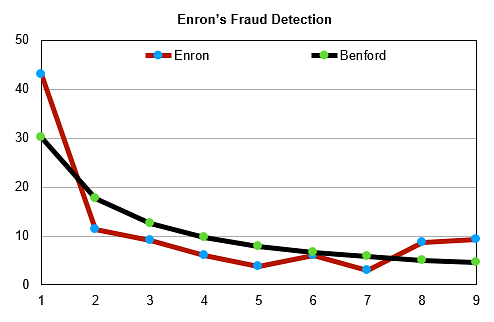

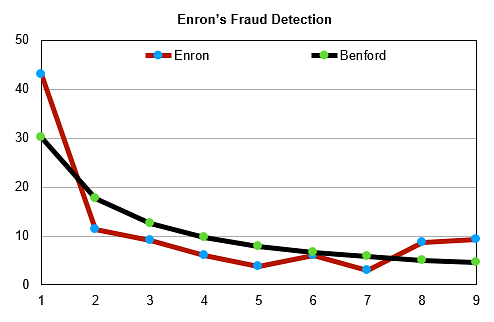

For instance, the global data for Covid-19 daily infections is fairly reliable as it fits Benford’s curve quite nicely.

Each of the two graphs (immediately above, clockwise second and fourth) represent the combined data for deaths and infections. The second graph represents UK data and the fourth one gives us US data. Both these graphs are in reasonable conformity with Benford’s curve. The US data seems to be a notch more reliable. Interestingly, the data for the for the UK has some issues since the digit 4 occurs as leading digit far more often than prescribed by the Benford curve. But in general, it is a good fit.

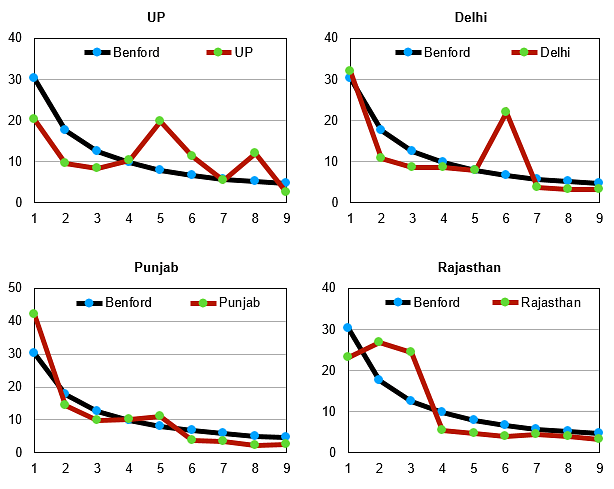

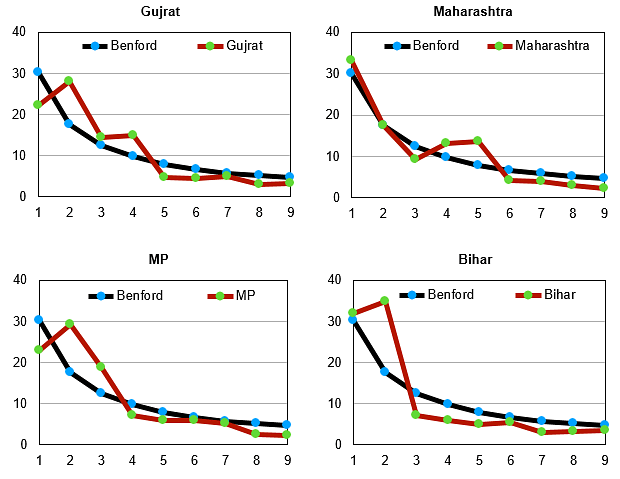

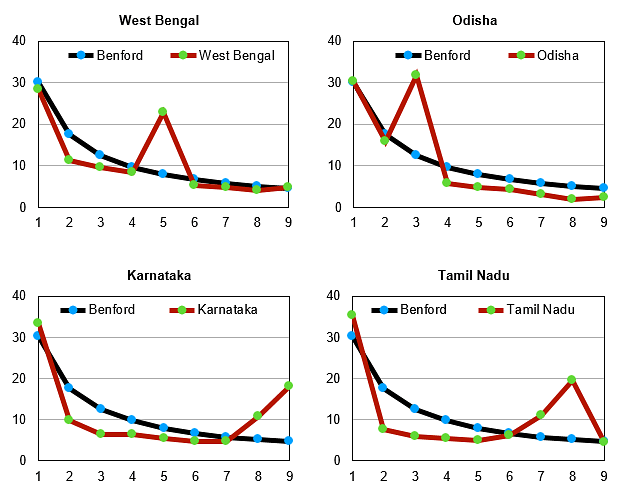

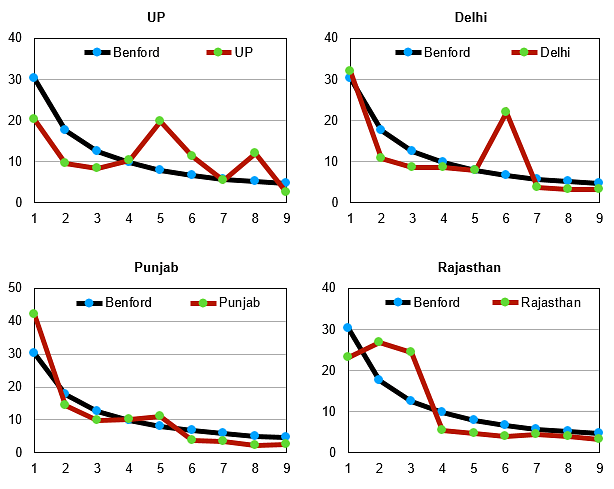

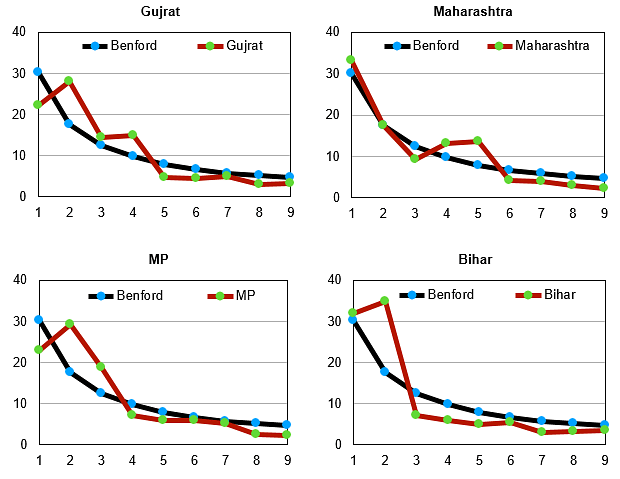

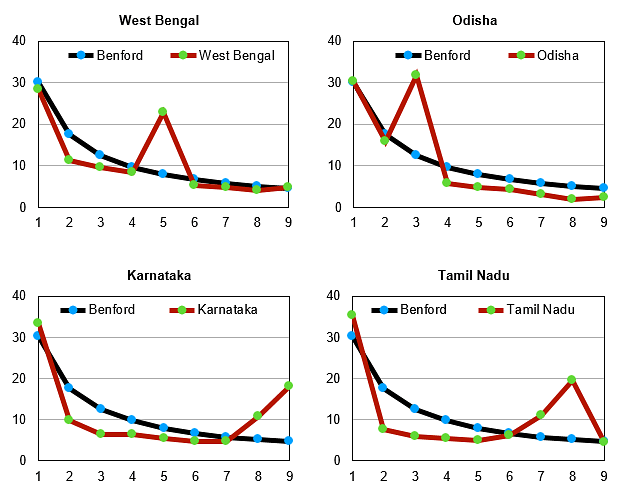

Henceforth we are examining statewide data for India and have merged — for each graph — the data for daily infections, daily deaths and daily recoveries. Thus, if the graph shows deviations from Benford’s Law, the implication will be that at least one of the three recordings of data categories has errors in it. But if this combined data curve fits Benford’s curve, then the inference is that all three sets of data are reliable. Merging the data points for the three categories helps bring greater clarity to the verification.

The India data

When it comes to India, the data for the entire nation has some issues but in general there is a passable fit. We must clarify that this indicates inaccuracy of data but does not necessarily indicate fraudulent recording. However, in general, when it comes to accuracy of data in India — for any kind of data — invariably issues and concerns arise. The sooner India learns the art and science of accurate data keeping the better it shall be for the nation.

Kerala’s data is quite reliable as it fits Benford’s curve quite nicely. Punjab also has fairly accurate data indicated by a very good fit between the Benford curve and the curve for its data. The biggest offenders seem to be Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. The curves for these two states are quite off the mark as can be seen by their graphs. Rajasthan and West Bengal are also not very encouraging. However, the one redeeming feature for so many of these states is the fact that several of their data points do seem to be in conformity with the Benford’s curve. This ultimately helps keep India’s curve in reasonable conformity with Benford’s curve. We leave the question of whether any of this data is fudged to the reader but certainly much of the statewide data is unreliable.

A healthcare worker collects sample for Covid testing. Assam has a caseload of 3.15 lakh and a total of 1,984 people have died of Covid in the state. (Representational image) | PTI

A healthcare worker collects sample for Covid testing. Assam has a caseload of 3.15 lakh and a total of 1,984 people have died of Covid in the state. (Representational image) | PTIDuring this global pandemic, several nations across different geographical regions, have had the accuracy of their Covid-19 data records looked at with a healthy dose of questioning. For instance, even with the best of intentions, some western nations have had difficulties in classifying their Covid-19 data. This does not necessarily imply deliberate misrepresentation of the data on part of the agencies responsible. It is just that a pandemic that has left the world shaken in so many ways will also, doubtless, affect data keeping. At the same time, when it comes to data records, it is of utmost importance to endeavour towards maintaining accuracy to the extent possible.

In such a situation, it is useful to try and gauge the accuracy or reliability of the data through various methods. One such fairly reliable means of measuring the accuracy of numeric data sets is a simple mathematical law that was discovered many decades ago and is generally known as the Benford’s Law. This easy to state and just as easy to understand law deals with gauging the reliability or accuracy of large data sets consisting of numeric data that has occurred in natural or non-artificial ways. In other words, the data set must consist of plenty of numbers and these numbers should have arisen without deliberate interference or manipulation. It is generally accepted that the law is meaningfully applicable in instances where the number of data points is at least 500. Also, the meaning of ‘naturally occurring data’ is best understood through illustrations such as of the type related to stock markets or tax records or population data.

Benford’s Law and its application

The law was discovered, actually rediscovered, by Charles Benford in 1938. To grasp this simple law, we need to understand the meaning of the term ‘leading digit’. Given any number, say 813, its leading or first digit is 8. Obviously, we can have only 9 leading digits in any combination viz. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. The law says that given a naturally arising collection of very, many numbers, the number of times each leading digit occurs as a percentage of the entire lot of leading digits is fixed. In other words, in the entire collection of leading digits arising from a naturally occurring collection of numbers associated with a phenomenon, the number 1 must occur about 30 per cent of the time; the digit 2 about 17 per cent of the time and so on in a certain decreasing order for the other 7 digits where 9 occurs 4.6 per cent of the time. Hence, if the data is true then in about 1000 numbers, 1 occurs as a leading digit about 300 times and so on. This is best illustrated through the following precisely stated table and also pictorially by the succeeding graphs.

What happens when in a given data set of leading digits, arising from numbers denoting a natural phenomenon, is not in conformity with the law? The answer is simple; there is a very high chance that the data is not reliable either because of inaccurate records or because of manipulation.

One of the best ways to contrast the actual data against that prescribed by Benford’s Law is visually, through a graph. That is precisely what we shall be doing for all figures in the article. We shall superimpose the curve given by the actual data (always in red) over the standard curve prescribed by Benford’s Law (always in black). The Benford curve shall look like a slide descending from the right to the left. The deviations of the curve representing the actual data vis a vis the Benford’s curve shall reveal unreliability of the data set.

The prowess of the law is best gauged by a look at the financial data of the now defunct former energy giant Enron Corporation. It is now well known that Enron had been fudging its financial data. This can be seen in the figure below where the data curve for Enron’s revenues is a very bad fit over the Benford curve. It is actually a no brainer to infer that Enron had heavily manipulated its financial data as can be seen by the number of significant deviations of the Enron data curve from the standard Benford curve.

Testing Covid data

We have in this article attempted to look at the data arising from Covid-19 cases across countries and across several states of India. Some very interesting insights emerge.

For instance, the global data for Covid-19 daily infections is fairly reliable as it fits Benford’s curve quite nicely.

Each of the two graphs (immediately above, clockwise second and fourth) represent the combined data for deaths and infections. The second graph represents UK data and the fourth one gives us US data. Both these graphs are in reasonable conformity with Benford’s curve. The US data seems to be a notch more reliable. Interestingly, the data for the for the UK has some issues since the digit 4 occurs as leading digit far more often than prescribed by the Benford curve. But in general, it is a good fit.

Henceforth we are examining statewide data for India and have merged — for each graph — the data for daily infections, daily deaths and daily recoveries. Thus, if the graph shows deviations from Benford’s Law, the implication will be that at least one of the three recordings of data categories has errors in it. But if this combined data curve fits Benford’s curve, then the inference is that all three sets of data are reliable. Merging the data points for the three categories helps bring greater clarity to the verification.

The India data

When it comes to India, the data for the entire nation has some issues but in general there is a passable fit. We must clarify that this indicates inaccuracy of data but does not necessarily indicate fraudulent recording. However, in general, when it comes to accuracy of data in India — for any kind of data — invariably issues and concerns arise. The sooner India learns the art and science of accurate data keeping the better it shall be for the nation.

Kerala’s data is quite reliable as it fits Benford’s curve quite nicely. Punjab also has fairly accurate data indicated by a very good fit between the Benford curve and the curve for its data. The biggest offenders seem to be Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. The curves for these two states are quite off the mark as can be seen by their graphs. Rajasthan and West Bengal are also not very encouraging. However, the one redeeming feature for so many of these states is the fact that several of their data points do seem to be in conformity with the Benford’s curve. This ultimately helps keep India’s curve in reasonable conformity with Benford’s curve. We leave the question of whether any of this data is fudged to the reader but certainly much of the statewide data is unreliable.

Israel - A PSYCHOTIC BREAK FROM REALITY?

Nadeem F. Paracha in The Dawn

Illustration by Abro

Illustration by Abro

The New York Times, in its May 28, 2021 issue, published a collage of photographs of 67 children under the age of 18 who had been killed in the recent Israeli air attacks on Gaza and by Hamas on Tel Aviv. Two of the children had been killed in Israel by shrapnel from rockets fired by Hamas. It is only natural for any normal human being to ask, how can one kill children?

Similar collages appear every year on social media of the over 140 students who were mercilessly gunned down in 2014 at the Army Public School in Peshawar. The killings were carried out by the militant organisation the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Most Pakistanis could not comprehend how even a militant group could massacre school children. But there were also those who questioned why the children were targeted.

The ‘why’ in this context is apparently understood at an individual level when certain individuals sexually assault children and often kill them. Psychologists are of the view that such individuals — paedophiles — are mostly men who have either suffered sexual abuse as children themselves, or are overwhelmed by certain psychological disorders that lead to developing questionable sexual urges.

In the 1982 anthology Behaviour Modification and Therapy, W.L. Marshall writes that paedophilia co-occurs with low self-esteem, depression and other personality disorders. These can be because of the individual’s own experiences as a sexually abused child or, according to the 2008 issue of the Journal of Psychiatric Research, paedophiles may have different brain structures which cause personality disorders and social failings, leading them to develop deviant sexual behaviours.

But why do some paedophiles end up murdering their young victims? This may be to eliminate the possibility of their victims naming them after the assault, or the young victims die because their bodies are still not developed to accommodate even the most basic sexual acts. According to a 1992 study by the Behavioural Science Unit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the US, some paedophiles can also develop sadism as a disorder, which eventually compels them to derive pleasure by inflicting pain and killing their young victims.

Why did Israel kill so many children in its bombardment of Gaza? Could it be that it has something in common with apocalyptic terror groups, for whom killing children is simply collateral damage in a divinely ordained cosmic battle?

Now the question is, are modern-day governments, militaries and terrorist groups that knowingly massacre children, also driven by the same sadistic impulses? Do they extract pleasure from slaughtering children? It is possible that military massacres that include the death of a large number of children are acts of frustration and blind rage by soldiers made to fight wars that are being lost.

The March 1968 ‘My Lai massacre’, carried out by US soldiers in Vietnam, is a case in point. Over 500 people, including children, were killed in that incident. Even women who were carrying babies in their arms, were shot dead. Just a month earlier, communist insurgents had attacked South Vietnamese cities held by US forces. The insurgents were driven out, but they were able to kill a large number of US soldiers. Also, the war in Vietnam had become unpopular in the US. Soldiers were dismayed by stories about returning US marines being insulted, ridiculed and rejected at home for fighting an unjust and immoral war.

Indeed, desperate armies have been known to kill the most vulnerable members of the enemy, such as children, in an attempt to psychologically compensate for their inability to fight effectively against their adult opponents. But what about the Israeli armed forces? What frustrations are they facing? They have successfully neutralised anti-Israel militancy. And the Palestinians and their supporters are no match against Israel’s war machine. So why did Israeli forces knowingly kill so many Palestinian children in Gaza?

A May 21, 2021 report published on the Al-Jazeera website quotes a Palestinian lawyer, Youssef al-Zayed, as saying that Israeli forces were ‘intentionally targeting minors to terrorise an entire generation from speaking out.’ Ever since 1987, Palestinian children have been in the forefront of protests against armed Israeli forces. The children are often armed with nothing more than stones.

What Israel is doing against its Arab population, and in the Palestinian Territories that are still largely under its control, can be called ‘democide.’ Coined by the American political scientist Rudolph Rummel, the word democide means acts of genocide by a government/ state against a segment of its own population. Such acts constitute the systematic elimination of people belonging to minority religious or ethnic communities. According to Rummel, this is done because the persecuted communities are perceived as being ‘future threats’ by the dominant community.

So, do terrorist outfits such as TTP, Islamic State and Boko Haram, for example, who are known to also target children, do so because they see children as future threats?

In a 2018 essay for the Journal of Strategic Studies, the forensic psychologist Karl Umbrasas writes that terror outfits who kill indiscriminately can be categorised as ‘apocalyptic groups.’ According to Umbrasas, such groups operate like ‘apocalyptic cults’ and are not restrained by the socio-political and moral restraints that compel non-apocalyptic militant outfits to only focus on attacking armed, non-civilian targets. Umbrasas writes that apocalyptic terror groups justify acts of indiscriminate destruction through their often distorted and violent interpretations of sacred texts.

Such groups are thus completely unrepentant about targeting even children. To them the children, too, are part of the problem that they are going to resolve through a ‘cosmic war.’ The idea of a cosmic war constitutes an imagined battle between metaphysical forces — good and evil — that is behind many cases of religion-related violence.

Interestingly, this was also how the Afghan civil war of the 1980s between Islamist groups and Soviet troops was framed by the US, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. The cosmic bit evaporated for the three states after the departure of Soviet troops, but the idea of the cosmic conflict remained in the minds of various terror groups in the region.

The moral codes of apocalyptic terror groups transcend those of the modern world. So, for example, on May 9 this year, when a terrorist group targeted a girls’ school in Afghanistan, killing 80, it is likely it saw girl students as part of the evil side in the divinely ordained cosmic war that the group imagines itself to be fighting.

This indeed is the result of a psychotic break from reality. But it is a reality that apocalyptic terror outfits do not accept. To them, this reality is a social construct. There is no value of the physical human body in such misshaped metaphysical ideas. Therefore, even if a cosmic war requires the killing of children, it is just the destruction of bodies, no matter what their size.

Illustration by Abro

Illustration by AbroThe New York Times, in its May 28, 2021 issue, published a collage of photographs of 67 children under the age of 18 who had been killed in the recent Israeli air attacks on Gaza and by Hamas on Tel Aviv. Two of the children had been killed in Israel by shrapnel from rockets fired by Hamas. It is only natural for any normal human being to ask, how can one kill children?

Similar collages appear every year on social media of the over 140 students who were mercilessly gunned down in 2014 at the Army Public School in Peshawar. The killings were carried out by the militant organisation the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Most Pakistanis could not comprehend how even a militant group could massacre school children. But there were also those who questioned why the children were targeted.

The ‘why’ in this context is apparently understood at an individual level when certain individuals sexually assault children and often kill them. Psychologists are of the view that such individuals — paedophiles — are mostly men who have either suffered sexual abuse as children themselves, or are overwhelmed by certain psychological disorders that lead to developing questionable sexual urges.

In the 1982 anthology Behaviour Modification and Therapy, W.L. Marshall writes that paedophilia co-occurs with low self-esteem, depression and other personality disorders. These can be because of the individual’s own experiences as a sexually abused child or, according to the 2008 issue of the Journal of Psychiatric Research, paedophiles may have different brain structures which cause personality disorders and social failings, leading them to develop deviant sexual behaviours.

But why do some paedophiles end up murdering their young victims? This may be to eliminate the possibility of their victims naming them after the assault, or the young victims die because their bodies are still not developed to accommodate even the most basic sexual acts. According to a 1992 study by the Behavioural Science Unit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the US, some paedophiles can also develop sadism as a disorder, which eventually compels them to derive pleasure by inflicting pain and killing their young victims.

Why did Israel kill so many children in its bombardment of Gaza? Could it be that it has something in common with apocalyptic terror groups, for whom killing children is simply collateral damage in a divinely ordained cosmic battle?

Now the question is, are modern-day governments, militaries and terrorist groups that knowingly massacre children, also driven by the same sadistic impulses? Do they extract pleasure from slaughtering children? It is possible that military massacres that include the death of a large number of children are acts of frustration and blind rage by soldiers made to fight wars that are being lost.

The March 1968 ‘My Lai massacre’, carried out by US soldiers in Vietnam, is a case in point. Over 500 people, including children, were killed in that incident. Even women who were carrying babies in their arms, were shot dead. Just a month earlier, communist insurgents had attacked South Vietnamese cities held by US forces. The insurgents were driven out, but they were able to kill a large number of US soldiers. Also, the war in Vietnam had become unpopular in the US. Soldiers were dismayed by stories about returning US marines being insulted, ridiculed and rejected at home for fighting an unjust and immoral war.

Indeed, desperate armies have been known to kill the most vulnerable members of the enemy, such as children, in an attempt to psychologically compensate for their inability to fight effectively against their adult opponents. But what about the Israeli armed forces? What frustrations are they facing? They have successfully neutralised anti-Israel militancy. And the Palestinians and their supporters are no match against Israel’s war machine. So why did Israeli forces knowingly kill so many Palestinian children in Gaza?

A May 21, 2021 report published on the Al-Jazeera website quotes a Palestinian lawyer, Youssef al-Zayed, as saying that Israeli forces were ‘intentionally targeting minors to terrorise an entire generation from speaking out.’ Ever since 1987, Palestinian children have been in the forefront of protests against armed Israeli forces. The children are often armed with nothing more than stones.

What Israel is doing against its Arab population, and in the Palestinian Territories that are still largely under its control, can be called ‘democide.’ Coined by the American political scientist Rudolph Rummel, the word democide means acts of genocide by a government/ state against a segment of its own population. Such acts constitute the systematic elimination of people belonging to minority religious or ethnic communities. According to Rummel, this is done because the persecuted communities are perceived as being ‘future threats’ by the dominant community.

So, do terrorist outfits such as TTP, Islamic State and Boko Haram, for example, who are known to also target children, do so because they see children as future threats?

In a 2018 essay for the Journal of Strategic Studies, the forensic psychologist Karl Umbrasas writes that terror outfits who kill indiscriminately can be categorised as ‘apocalyptic groups.’ According to Umbrasas, such groups operate like ‘apocalyptic cults’ and are not restrained by the socio-political and moral restraints that compel non-apocalyptic militant outfits to only focus on attacking armed, non-civilian targets. Umbrasas writes that apocalyptic terror groups justify acts of indiscriminate destruction through their often distorted and violent interpretations of sacred texts.

Such groups are thus completely unrepentant about targeting even children. To them the children, too, are part of the problem that they are going to resolve through a ‘cosmic war.’ The idea of a cosmic war constitutes an imagined battle between metaphysical forces — good and evil — that is behind many cases of religion-related violence.

Interestingly, this was also how the Afghan civil war of the 1980s between Islamist groups and Soviet troops was framed by the US, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. The cosmic bit evaporated for the three states after the departure of Soviet troops, but the idea of the cosmic conflict remained in the minds of various terror groups in the region.

The moral codes of apocalyptic terror groups transcend those of the modern world. So, for example, on May 9 this year, when a terrorist group targeted a girls’ school in Afghanistan, killing 80, it is likely it saw girl students as part of the evil side in the divinely ordained cosmic war that the group imagines itself to be fighting.

This indeed is the result of a psychotic break from reality. But it is a reality that apocalyptic terror outfits do not accept. To them, this reality is a social construct. There is no value of the physical human body in such misshaped metaphysical ideas. Therefore, even if a cosmic war requires the killing of children, it is just the destruction of bodies, no matter what their size.

Just don’t do it: 10 exercise myths

We all believe we should exercise more. So why is it so hard to keep it up? Daniel E Lieberman, Harvard professor of evolutionary biology, explodes the most common and unhelpful workout myths by Daniel E Lieberman in The Guardian

Yesterday at an outdoor coffee shop, I met my old friend James in person for the first time since the pandemic began. Over the past year on Zoom, he looked just fine, but in 3D there was no hiding how much weight he’d gained. As we sat down with our cappuccinos, I didn’t say a thing, but the first words out of his mouth were: “Yes, yes, I’m now 20lb too heavy and in pathetic shape. I need to diet and exercise, but I don’t want to talk about it!”

If you feel like James, you are in good company. With the end of the Covid-19 pandemic now plausibly in sight, 70% of Britons say they hope to eat a healthier diet, lose weight and exercise more. But how? Every year, millions of people vow to be more physically active, but the vast majority of these resolutions fail. We all know what happens. After a week or two of sticking to a new exercise regime we gradually slip back into old habits and then feel bad about ourselves.

Clearly, we need a new approach because the most common ways we promote exercise – medicalising and commercialising it – aren’t widely effective. The proof is in the pudding: most adults in high-income countries, such as the UK and US, don’t get the minimum of 150 minutes per week of physical activity recommended by most health professionals. Everyone knows exercise is healthy, but prescribing and selling it rarely works.

I think we can do better by looking beyond the weird world in which we live to consider how our ancestors as well as people in other cultures manage to be physically active. This kind of evolutionary anthropological perspective reveals 10 unhelpful myths about exercise. Rejecting them won’t transform you suddenly into an Olympic athlete, but they might help you turn over a new leaf without feeling bad about yourself.

Myth 1: It’s normal to exercise

Whenever you move to do anything, you’re engaging in physical activity. In contrast, exercise is voluntary physical activity undertaken for the sake of fitness. You may think exercise is normal, but it’s a very modern behaviour. Instead, for millions of years, humans were physically active for only two reasons: when it was necessary or rewarding. Necessary physical activities included getting food and doing other things to survive. Rewarding activities included playing, dancing or training to have fun or to develop skills. But no one in the stone age ever went for a five-mile jog to stave off decrepitude, or lifted weights whose sole purpose was to be lifted.

Myth 2: Avoiding exertion means you are lazy

Whenever I see an escalator next to a stairway, a little voice in my brain says, “Take the escalator.” Am I lazy? Although escalators didn’t exist in bygone days, that instinct is totally normal because physical activity costs calories that until recently were always in short supply (and still are for many people). When food is limited, every calorie spent on physical activity is a calorie not spent on other critical functions, such as maintaining our bodies, storing energy and reproducing. Because natural selection ultimately cares only about how many offspring we have, our hunter-gatherer ancestors evolved to avoid needless exertion – exercise – unless it was rewarding. So don’t feel bad about the natural instincts that are still with us. Instead, accept that they are normal and hard to overcome.

Myth 3: Sitting is the new smoking

You’ve probably heard scary statistics that we sit too much and it’s killing us. Yes, too much physical inactivity is unhealthy, but let’s not demonise a behaviour as normal as sitting. People in every culture sit a lot. Even hunter-gatherers who lack furniture sit about 10 hours a day, as much as most westerners. But there are more and less healthy ways to sit. Studies show that people who sit actively by getting up every 10 or 15 minutes wake up their metabolisms and enjoy better long-term health than those who sit inertly for hours on end. In addition, leisure-time sitting is more strongly associated with negative health outcomes than work-time sitting. So if you work all day in a chair, get up regularly, fidget and try not to spend the rest of the day in a chair, too.

Myth 4: Our ancestors were hard-working, strong and fast

A common myth is that people uncontaminated by civilisation are incredible natural-born athletes who are super-strong, super-fast and able to run marathons easily. Not true. Most hunter-gatherers are reasonably fit, but they are only moderately strong and not especially fast. Their lives aren’t easy, but on average they spend only about two to three hours a day doing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. It is neither normal nor necessary to be ultra-fit and ultra-strong.

Myth 5: You can’t lose weight walking

Until recently just about every weight-loss programme involved exercise. Recently, however, we keep hearing that we can’t lose weight from exercise because most workouts don’t burn that many calories and just make us hungry so we eat more. The truth is that you can lose more weight much faster through diet rather than exercise, especially moderate exercise such as 150 minutes a week of brisk walking. However, longer durations and higher intensities of exercise have been shown to promote gradual weight loss. Regular exercise also helps prevent weight gain or regain after diet. Every diet benefits from including exercise.

Myth 6: Running will wear out your knees

Many people are scared of running because they’re afraid it will ruin their knees. These worries aren’t totally unfounded since knees are indeed the most common location of runners’ injuries. But knees and other joints aren’t like a car’s shock absorbers that wear out with overuse. Instead, running, walking and other activities have been shown to keep knees healthy, and numerous high-quality studies show that runners are, if anything, less likely to develop knee osteoarthritis. The strategy to avoiding knee pain is to learn to run properly and train sensibly (which means not increasing your mileage by too much too quickly).

Myth 7: It’s normal to be less active as we age

After many decades of hard work, don’t you deserve to kick up your heels and take it easy in your golden years? Not so. Despite rumours that our ancestors’ life was nasty, brutish and short, hunter-gatherers who survive childhood typically live about seven decades, and they continue to work moderately as they age. The truth is we evolved to be grandparents in order to be active in order to provide food for our children and grandchildren. In turn, staying physically active as we age stimulates myriad repair and maintenance processes that keep our bodies humming. Numerous studies find that exercise is healthier the older we get.

Myth 8: There is an optimal dose/type of exercise

One consequence of medicalising exercise is that we prescribe it. But how much and what type? Many medical professionals follow the World Health Organisation’s recommendation of at least 150 minutes a week of moderate or 75 minutes a week of vigorous exercise for adults. In truth, this is an arbitrary prescription because how much to exercise depends on dozens of factors, such as your fitness, age, injury history and health concerns. Remember this: no matter how unfit you are, even a little exercise is better than none. Just an hour a week (eight minutes a day) can yield substantial dividends. If you can do more, that’s great, but very high doses yield no additional benefits. It’s also healthy to vary the kinds of exercise you do, and do regular strength training as you age.

Myth 9: ‘Just do it’ works

Let’s face it, most people don’t like exercise and have to overcome natural tendencies to avoid it. For most of us, telling us to “just do it” doesn’t work any better than telling a smoker or a substance abuser to “just say no!” To promote exercise, we typically prescribe it and sell it, but let’s remember that we evolved to be physically active for only two reasons: it was necessary or rewarding. So let’s find ways to do both: make it necessary and rewarding. Of the many ways to accomplish this, I think the best is to make exercise social. If you agree to meet friends to exercise regularly you’ll be obliged to show up, you’ll have fun and you’ll keep each other going.

Myth 10: Exercise is a magic bullet

Finally, let’s not oversell exercise as medicine. Although we never evolved to exercise, we did evolve to be physically active just as we evolved to drink water, breathe air and have friends. Thus, it’s the absence of physical activity that makes us more vulnerable to many illnesses, both physical and mental. In the modern, western world we no longer have to be physically active, so we invented exercise, but it is not a magic bullet that guarantees good health. Fortunately, just a little exercise can slow the rate at which you age and substantially reduce your chances of getting a wide range of diseases, especially as you age. It can also be fun – something we’ve all been missing during this dreadful pandemic.

Yesterday at an outdoor coffee shop, I met my old friend James in person for the first time since the pandemic began. Over the past year on Zoom, he looked just fine, but in 3D there was no hiding how much weight he’d gained. As we sat down with our cappuccinos, I didn’t say a thing, but the first words out of his mouth were: “Yes, yes, I’m now 20lb too heavy and in pathetic shape. I need to diet and exercise, but I don’t want to talk about it!”

If you feel like James, you are in good company. With the end of the Covid-19 pandemic now plausibly in sight, 70% of Britons say they hope to eat a healthier diet, lose weight and exercise more. But how? Every year, millions of people vow to be more physically active, but the vast majority of these resolutions fail. We all know what happens. After a week or two of sticking to a new exercise regime we gradually slip back into old habits and then feel bad about ourselves.

Clearly, we need a new approach because the most common ways we promote exercise – medicalising and commercialising it – aren’t widely effective. The proof is in the pudding: most adults in high-income countries, such as the UK and US, don’t get the minimum of 150 minutes per week of physical activity recommended by most health professionals. Everyone knows exercise is healthy, but prescribing and selling it rarely works.

I think we can do better by looking beyond the weird world in which we live to consider how our ancestors as well as people in other cultures manage to be physically active. This kind of evolutionary anthropological perspective reveals 10 unhelpful myths about exercise. Rejecting them won’t transform you suddenly into an Olympic athlete, but they might help you turn over a new leaf without feeling bad about yourself.

Myth 1: It’s normal to exercise

Whenever you move to do anything, you’re engaging in physical activity. In contrast, exercise is voluntary physical activity undertaken for the sake of fitness. You may think exercise is normal, but it’s a very modern behaviour. Instead, for millions of years, humans were physically active for only two reasons: when it was necessary or rewarding. Necessary physical activities included getting food and doing other things to survive. Rewarding activities included playing, dancing or training to have fun or to develop skills. But no one in the stone age ever went for a five-mile jog to stave off decrepitude, or lifted weights whose sole purpose was to be lifted.

Myth 2: Avoiding exertion means you are lazy

Whenever I see an escalator next to a stairway, a little voice in my brain says, “Take the escalator.” Am I lazy? Although escalators didn’t exist in bygone days, that instinct is totally normal because physical activity costs calories that until recently were always in short supply (and still are for many people). When food is limited, every calorie spent on physical activity is a calorie not spent on other critical functions, such as maintaining our bodies, storing energy and reproducing. Because natural selection ultimately cares only about how many offspring we have, our hunter-gatherer ancestors evolved to avoid needless exertion – exercise – unless it was rewarding. So don’t feel bad about the natural instincts that are still with us. Instead, accept that they are normal and hard to overcome.

‘For most of us, telling us to “Just do it” doesn’t work’: exercise needs to feel rewarding as well as necessary. Photograph: Dan Saelinger/trunkarchive.com

Myth 3: Sitting is the new smoking

You’ve probably heard scary statistics that we sit too much and it’s killing us. Yes, too much physical inactivity is unhealthy, but let’s not demonise a behaviour as normal as sitting. People in every culture sit a lot. Even hunter-gatherers who lack furniture sit about 10 hours a day, as much as most westerners. But there are more and less healthy ways to sit. Studies show that people who sit actively by getting up every 10 or 15 minutes wake up their metabolisms and enjoy better long-term health than those who sit inertly for hours on end. In addition, leisure-time sitting is more strongly associated with negative health outcomes than work-time sitting. So if you work all day in a chair, get up regularly, fidget and try not to spend the rest of the day in a chair, too.

Myth 4: Our ancestors were hard-working, strong and fast

A common myth is that people uncontaminated by civilisation are incredible natural-born athletes who are super-strong, super-fast and able to run marathons easily. Not true. Most hunter-gatherers are reasonably fit, but they are only moderately strong and not especially fast. Their lives aren’t easy, but on average they spend only about two to three hours a day doing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. It is neither normal nor necessary to be ultra-fit and ultra-strong.

Myth 5: You can’t lose weight walking

Until recently just about every weight-loss programme involved exercise. Recently, however, we keep hearing that we can’t lose weight from exercise because most workouts don’t burn that many calories and just make us hungry so we eat more. The truth is that you can lose more weight much faster through diet rather than exercise, especially moderate exercise such as 150 minutes a week of brisk walking. However, longer durations and higher intensities of exercise have been shown to promote gradual weight loss. Regular exercise also helps prevent weight gain or regain after diet. Every diet benefits from including exercise.

Myth 6: Running will wear out your knees

Many people are scared of running because they’re afraid it will ruin their knees. These worries aren’t totally unfounded since knees are indeed the most common location of runners’ injuries. But knees and other joints aren’t like a car’s shock absorbers that wear out with overuse. Instead, running, walking and other activities have been shown to keep knees healthy, and numerous high-quality studies show that runners are, if anything, less likely to develop knee osteoarthritis. The strategy to avoiding knee pain is to learn to run properly and train sensibly (which means not increasing your mileage by too much too quickly).

Myth 7: It’s normal to be less active as we age

After many decades of hard work, don’t you deserve to kick up your heels and take it easy in your golden years? Not so. Despite rumours that our ancestors’ life was nasty, brutish and short, hunter-gatherers who survive childhood typically live about seven decades, and they continue to work moderately as they age. The truth is we evolved to be grandparents in order to be active in order to provide food for our children and grandchildren. In turn, staying physically active as we age stimulates myriad repair and maintenance processes that keep our bodies humming. Numerous studies find that exercise is healthier the older we get.

Myth 8: There is an optimal dose/type of exercise

One consequence of medicalising exercise is that we prescribe it. But how much and what type? Many medical professionals follow the World Health Organisation’s recommendation of at least 150 minutes a week of moderate or 75 minutes a week of vigorous exercise for adults. In truth, this is an arbitrary prescription because how much to exercise depends on dozens of factors, such as your fitness, age, injury history and health concerns. Remember this: no matter how unfit you are, even a little exercise is better than none. Just an hour a week (eight minutes a day) can yield substantial dividends. If you can do more, that’s great, but very high doses yield no additional benefits. It’s also healthy to vary the kinds of exercise you do, and do regular strength training as you age.

Myth 9: ‘Just do it’ works

Let’s face it, most people don’t like exercise and have to overcome natural tendencies to avoid it. For most of us, telling us to “just do it” doesn’t work any better than telling a smoker or a substance abuser to “just say no!” To promote exercise, we typically prescribe it and sell it, but let’s remember that we evolved to be physically active for only two reasons: it was necessary or rewarding. So let’s find ways to do both: make it necessary and rewarding. Of the many ways to accomplish this, I think the best is to make exercise social. If you agree to meet friends to exercise regularly you’ll be obliged to show up, you’ll have fun and you’ll keep each other going.

Myth 10: Exercise is a magic bullet

Finally, let’s not oversell exercise as medicine. Although we never evolved to exercise, we did evolve to be physically active just as we evolved to drink water, breathe air and have friends. Thus, it’s the absence of physical activity that makes us more vulnerable to many illnesses, both physical and mental. In the modern, western world we no longer have to be physically active, so we invented exercise, but it is not a magic bullet that guarantees good health. Fortunately, just a little exercise can slow the rate at which you age and substantially reduce your chances of getting a wide range of diseases, especially as you age. It can also be fun – something we’ve all been missing during this dreadful pandemic.

Saturday, 5 June 2021

Friday, 4 June 2021

Why the draconian sedition law must go

Faizan Mustafa in The Indian Express

Whether people in a free country committed to the liberty of thought and freedom of expression can be criminally punished for expressing their opinion about the government is the moot question. Does the government have the right to affection? What is the origin of the law of sedition in India? How did the framers of the Constitution deal with it? How have our courts interpreted this sedition provision?

In the last seven years, an extreme nationalist ideology actively supported by pliant journalists repeatedly used aggressive nationalism to suppress dissent, mock liberals and civil libertarians and several governments routinely invoked Section 124-A that penalises sedition. An 84-year-old Jesuit priest, Stan Swamy, and 21-year-old Disha Ravi were not spared. A number of CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act) protesters are facing sedition charges. NCRB data shows that between 2016 to 2019, there has been a whopping 160 per cent increase in the filing of sedition charges with a conviction rate of just 3.3 per cent. Of the 96 people charged in 2019, only two could be convicted.

On Thursday, a two-judge bench of Justices U U Lalit and Vineet Saran observed that “every journalist is entitled to the protection under the Kedar Nath judgment (1962)” on the petition filed by journalist Vinod Dua. Dua had sought the quashing of an FIR against him filed by a BJP leader of Himachal Pradesh. The bench took eight months to pronounce its order as arguments had concluded on October 6, 2020.

Justice Lalit in his 117-page historic judgment demolished all the arguments against the wider application of the sedition provision. The court entertained Dua’s writ petition under Article 32 as the Himachal Pradesh police failed to complete the investigation and submit its report under Section 173 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. The Court found that statements attributed to Dua that the Prime Minister had used deaths and terror threats to garner votes were indeed not made in the talk show on March 30, 2020.

The Court relied on the Kedar Nath judgement in which the apex court had held that a citizen has the right to say or write whatever he likes about the government or its measures by way of criticism so long as he does not incite people to violence against the government or with the intention of creating public disorder. Section 124A read along with explanations is not attracted without such an allusion to violence. The Court concluded that statements made by Dua about masks, ventilators, migrant workers, etc. were not seditious and were mere disapprobation so that Covid management improves. The same were certainly not made to incite people to indulge in violence or create any disorder. The Court in Para 44 concluded that Dua’s prosecution would be unjust and would be violative of the freedom of speech.

Governments of opposition parties, including the Congress, have also indiscriminately invoked sedition charges against intellectuals, writers, dissenters and protesters. In fact, it was a Congress government that had made sedition a cognisable offence in 1974. Arundhati Roy, Aseem Trivedi, Binayak Sen and even those who opposed the nuclear plant in Kudankulam, Tamil Nadu and the expansion of the Sterlite plant in Thoothukudi were booked under Sec 124-A.

Section 124-A was not a part of the original Indian Penal Code drafted by Lord Macaulay and treason was confined just to levying war. It was Sir James Fitzjames Stephen who subsequently got it inserted in 1870 in response to the Wahabi movement that had asked Muslims to initiate jihad against the colonial regime. While introducing the Bill, he argued that Wahabis are going from village to village and preaching that it was the sacred religious duty of Muslims to wage a war against British rule. Stephen himself was interested in having provisions similar to the UK Treason Felony Act 1848 because of his strong agreement with the Lockean contractual notion of allegiance to the king and deference to the state.

Mahatma Gandhi, during his trial in 1922, termed Section 124-A as the “prince among the political sections of IPC designed to suppress liberty of the citizen”. He went on to tell the judge that “affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by law. If one has no affection for a person or system, one should be free to give fullest expression to his disaffection so long as it does not contemplate, promote or incite to violence”. Though Justice Maurice Gwyer in Niharendu Dutt Majumdar (1942) had narrowed the provision and held that public disorder was the essence of the offence, the Privy Council in Sadashiv Narayan Bhalerao (1947) relying on Explanation 1 observed public disorder was not necessary to complete the offence.

Strangely, the Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee (April 29, 1947) headed by Sardar Patel included sedition as a legitimate ground to restrict free speech. When Patel was criticised by other members of the Constituent Assembly, he dropped it. Constitutionally, Section 124A being a pre-Constitution law that is inconsistent with Article 19(1)(a), on the commencement of the Constitution, had become void. In fact, it was struck down by the Punjab High Court in Tara Singh Gopi Chand (1951).

Justice Lalit ought to have clarified the distinction between “government established by law” and “persons for the time being engaged in carrying on the administration” as the visible symbol of the state made by the Court in Kedar Nath. The very existence of the state will be in jeopardy if the government established by law is subverted. This observation did require some clarification by the Court as the state and government are not the same. Governments come and go but the Indian state is a permanent entity. Criticism of ministers cannot be equated with the creation of disaffection against the State. No government, as Mahatma Gandhi told Judge R S Broomfield, has a right to love and affection. India of the 21st century should not think like Stephen who was too worried about Macaulay’s code not penalising criticism of the government, however severe, hostile, unfair or disingenuous. We must understand that no slogan by itself, howsoever provocative such as “Khalistan Zindabad” can be legitimately termed as seditious as per the Balwant Singh (1995) judgment of the Supreme Court.

The Congress’s loss in the 2019 general election is attributed to, among other reasons, its manifesto’s promise that it would remove the sedition provision if voted to office. In 2018, the Law Commission had recommended that the sedition law should not be used to curb free speech. Let the criminal law revision committee working under the Ministry of Home Affairs make the bold recommendation of dropping the draconian law. A political consensus needs to be forged on this issue.

Whether people in a free country committed to the liberty of thought and freedom of expression can be criminally punished for expressing their opinion about the government is the moot question. Does the government have the right to affection? What is the origin of the law of sedition in India? How did the framers of the Constitution deal with it? How have our courts interpreted this sedition provision?

In the last seven years, an extreme nationalist ideology actively supported by pliant journalists repeatedly used aggressive nationalism to suppress dissent, mock liberals and civil libertarians and several governments routinely invoked Section 124-A that penalises sedition. An 84-year-old Jesuit priest, Stan Swamy, and 21-year-old Disha Ravi were not spared. A number of CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act) protesters are facing sedition charges. NCRB data shows that between 2016 to 2019, there has been a whopping 160 per cent increase in the filing of sedition charges with a conviction rate of just 3.3 per cent. Of the 96 people charged in 2019, only two could be convicted.

On Thursday, a two-judge bench of Justices U U Lalit and Vineet Saran observed that “every journalist is entitled to the protection under the Kedar Nath judgment (1962)” on the petition filed by journalist Vinod Dua. Dua had sought the quashing of an FIR against him filed by a BJP leader of Himachal Pradesh. The bench took eight months to pronounce its order as arguments had concluded on October 6, 2020.

Justice Lalit in his 117-page historic judgment demolished all the arguments against the wider application of the sedition provision. The court entertained Dua’s writ petition under Article 32 as the Himachal Pradesh police failed to complete the investigation and submit its report under Section 173 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. The Court found that statements attributed to Dua that the Prime Minister had used deaths and terror threats to garner votes were indeed not made in the talk show on March 30, 2020.

The Court relied on the Kedar Nath judgement in which the apex court had held that a citizen has the right to say or write whatever he likes about the government or its measures by way of criticism so long as he does not incite people to violence against the government or with the intention of creating public disorder. Section 124A read along with explanations is not attracted without such an allusion to violence. The Court concluded that statements made by Dua about masks, ventilators, migrant workers, etc. were not seditious and were mere disapprobation so that Covid management improves. The same were certainly not made to incite people to indulge in violence or create any disorder. The Court in Para 44 concluded that Dua’s prosecution would be unjust and would be violative of the freedom of speech.

Governments of opposition parties, including the Congress, have also indiscriminately invoked sedition charges against intellectuals, writers, dissenters and protesters. In fact, it was a Congress government that had made sedition a cognisable offence in 1974. Arundhati Roy, Aseem Trivedi, Binayak Sen and even those who opposed the nuclear plant in Kudankulam, Tamil Nadu and the expansion of the Sterlite plant in Thoothukudi were booked under Sec 124-A.

Section 124-A was not a part of the original Indian Penal Code drafted by Lord Macaulay and treason was confined just to levying war. It was Sir James Fitzjames Stephen who subsequently got it inserted in 1870 in response to the Wahabi movement that had asked Muslims to initiate jihad against the colonial regime. While introducing the Bill, he argued that Wahabis are going from village to village and preaching that it was the sacred religious duty of Muslims to wage a war against British rule. Stephen himself was interested in having provisions similar to the UK Treason Felony Act 1848 because of his strong agreement with the Lockean contractual notion of allegiance to the king and deference to the state.

Mahatma Gandhi, during his trial in 1922, termed Section 124-A as the “prince among the political sections of IPC designed to suppress liberty of the citizen”. He went on to tell the judge that “affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by law. If one has no affection for a person or system, one should be free to give fullest expression to his disaffection so long as it does not contemplate, promote or incite to violence”. Though Justice Maurice Gwyer in Niharendu Dutt Majumdar (1942) had narrowed the provision and held that public disorder was the essence of the offence, the Privy Council in Sadashiv Narayan Bhalerao (1947) relying on Explanation 1 observed public disorder was not necessary to complete the offence.

Strangely, the Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee (April 29, 1947) headed by Sardar Patel included sedition as a legitimate ground to restrict free speech. When Patel was criticised by other members of the Constituent Assembly, he dropped it. Constitutionally, Section 124A being a pre-Constitution law that is inconsistent with Article 19(1)(a), on the commencement of the Constitution, had become void. In fact, it was struck down by the Punjab High Court in Tara Singh Gopi Chand (1951).

Justice Lalit ought to have clarified the distinction between “government established by law” and “persons for the time being engaged in carrying on the administration” as the visible symbol of the state made by the Court in Kedar Nath. The very existence of the state will be in jeopardy if the government established by law is subverted. This observation did require some clarification by the Court as the state and government are not the same. Governments come and go but the Indian state is a permanent entity. Criticism of ministers cannot be equated with the creation of disaffection against the State. No government, as Mahatma Gandhi told Judge R S Broomfield, has a right to love and affection. India of the 21st century should not think like Stephen who was too worried about Macaulay’s code not penalising criticism of the government, however severe, hostile, unfair or disingenuous. We must understand that no slogan by itself, howsoever provocative such as “Khalistan Zindabad” can be legitimately termed as seditious as per the Balwant Singh (1995) judgment of the Supreme Court.

The Congress’s loss in the 2019 general election is attributed to, among other reasons, its manifesto’s promise that it would remove the sedition provision if voted to office. In 2018, the Law Commission had recommended that the sedition law should not be used to curb free speech. Let the criminal law revision committee working under the Ministry of Home Affairs make the bold recommendation of dropping the draconian law. A political consensus needs to be forged on this issue.

Have you seen Groupthink in action?

Tim Harford in The FT

In his acid parliamentary testimony last week, Dominic Cummings, the prime minister’s former chief adviser, blamed a lot of different people and things for the UK’s failure to fight Covid-19 — including “groupthink”.

Groupthink is unlikely to fight back. It already has a terrible reputation, not helped by its Orwellian ring, and the term is used so often that I begin to fear that we have groupthink about groupthink.

So let’s step back. Groupthink was made famous in a 1972 book by psychologist Irving Janis. He was fascinated by the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961, in which a group of perfectly intelligent people in John F Kennedy’s administration made a series of perfectly ridiculous decisions to support a botched coup in Cuba. How had that happened? How can groups of smart people do such stupid things?

An illuminating metaphor from Scott Page, author of The Difference, a book about the power of diversity, is that of the cognitive toolbox. A good toolbox is not the same thing as a toolbox full of good tools: two dozen top-quality hammers will not do the job. Instead, what’s needed is variety: a hammer, pliers, a saw, a choice of screwdrivers and more.

This is obvious enough and, in principle, it should be obvious for decision-making too: a group needs a range of ideas, skills, experience and perspectives. Yet when you put three hammers on a hiring committee, they are likely to hire another hammer. This “homophily” — hanging out with people like ourselves — is the original sin of group decision-making, and there is no mystery as to how it happens.

But things get worse. One problem, investigated by Cass Sunstein and Reid Hastie in their book Wiser, is that groups intensify existing biases. One study looked at group discussions about then-controversial topics (climate change, same-sex marriage, affirmative action) by groups in left-leaning Boulder, Colorado, and in right-leaning Colorado Springs.

Each group contained six individuals with a range of views, but after discussing those views with each other, the Boulder groups bunched sharply to the left and the Colorado Springs groups bunched similarly to the right, becoming both more extreme and more uniform within the group. In some cases, the emergent view of the group was more extreme than the prior view of any single member.

One reason for this is that when surrounded with fellow travellers, people became more confident in their own views. They felt reassured by the support of others.

Meanwhile, people with contrary views tended to stay silent. Few people enjoy being publicly outnumbered. As a result, a false consensus emerged, with potential dissenters censoring themselves and the rest of the group gaining a misplaced sense of unanimity.

The Colorado experiments studied polarisation but this is not just a problem of polarisation. Groups tend to seek common ground on any subject from politics to the weather, a fact revealed by “hidden profile” psychology experiments. In such experiments, groups are given a task (for example, to choose the best candidate for a job) and each member of the group is given different pieces of information.

One might hope that each individual would share everything they knew, but instead what tends to happen is that people focus, redundantly, on what everybody already knows, rather than unearthing facts known to only one individual. The result is a decision-making disaster.

These “hidden profile” studies point to the heart of the problem: group discussions aren’t just about sharing information and making wise decisions. They are about cohesion — or, at least, finding common ground to chat about.

Reading Charlan Nemeth’s No! The Power of Disagreement In A World That Wants To Get Along, one theme is that while dissent leads to better, more robust decisions, it also leads to discomfort and even distress. Disagreement is valuable but agreement feels so much more comfortable.

There is no shortage of solutions to the problem of groupthink, but to list them is to understand why they are often overlooked. The first and simplest is to embrace decision-making processes that require disagreement: appoint a “devil’s advocate” whose job is to be a contrarian, or practise “red-teaming”, with an internal group whose task is to play the role of hostile actors (hackers, invaders or simply critics) and to find vulnerabilities. The evidence suggests that red-teaming works better than having a devil’s advocate, perhaps because dissent needs strength in numbers.

A more fundamental reform is to ensure that there is a real diversity of skills, experience and perspectives in the room: the screwdrivers and the saws as well as the hammers. This seems to be murderously hard.

When it comes to social interaction, the aphorism is wrong: opposites do not attract. We unconsciously surround ourselves with like-minded people.

Indeed, the process is not always unconscious. Boris Johnson’s cabinet could have contained Greg Clark and Jeremy Hunt, the two senior Conservative backbenchers who chair the committees to which Dominic Cummings gave his evidence about groupthink. But it does not. Why? Because they disagree with him too often.

The right groups, with the right processes, can make excellent decisions. But most of us don’t join groups to make better decisions. We join them because we want to belong. Groupthink persists because groupthink feels good.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)