'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Wednesday 10 April 2024

Wednesday 21 February 2024

Thursday 3 August 2023

Tuesday 1 November 2022

Friday 29 July 2022

The strange case of the cricket match that helped fund Imran Khan’s political rise

Simon Clark in The FT

At the height of his success, the Pakistani tycoon Arif Naqvi invited cricket superstar Imran Khan and hundreds of bankers, lawyers and investors to his walled country estate in the Oxfordshire village of Wootton for weekends of sport and drinking. The host was the founder of the Dubai-based Abraaj Group, then one of the largest private equity firms operating in emerging markets, with billions of dollars under management.

At the “Wootton T20 Cup”, over which Naqvi presided from 2010 to 2012, the main event was a cricket tournament between teams with invented names: the Peshawar Perverts or the Faisalabad Fothermuckers. They played on an immaculate pitch amid 14 acres of formal gardens and parkland at Wootton Place, Naqvi’s 17th-century residence. Veteran cricket commentator Henry Blofeld attended along with expert umpires and film crews.

“You can choose to play in order to impress or make a fool of yourself, or alternatively just to be an innocent bystander,” Naqvi wrote in an invitation to the event. The guests were asked to pay between £2,000 and £2,500 each to attend, with the money going to unspecified “philanthropic causes”, Naqvi said.

It is the type of charity fundraiser repeated up and down the UK every summer. What makes it unusual is that the ultimate benefactor was a political party in Pakistan. The fees were paid to Wootton Cricket Ltd, which, despite the name, was in fact a Cayman Islands-incorporated company owned by Naqvi and the money was being used to bankroll Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, Khan’s political party. Funds poured into Wootton Cricket from companies and individuals, including at least £2mn from a United Arab Emirates government minister who is also a member of the Abu Dhabi royal family.

Pakistan forbids foreign nationals and companies from funding political parties, but Abraaj emails and internal documents seen by the Financial Times, including a bank statement covering the period between February 28 and May 30 2013 for a Wootton Cricket account in the UAE, show that both companies and foreign nationals as well as citizens of Pakistan sent millions of dollars to Wootton Cricket — before money was transferred from the account to Pakistan for the PTI.

The funding of the party is at the centre of a years-long investigation by the Election Commission of Pakistan, an inquiry that has taken on even greater importance as Khan — who lost office in April — plots a political comeback.

But back in 2013, Khan — a World Cup-winning cricket captain — was riding a wave of popular support and campaigning to upend Pakistan’s politics on an anti-corruption ticket. He presented himself to the electorate as a democratic reformer — born in Pakistan and with experience of living in the west — who could break the hold of the political family dynasties that had dominated the country for decades.

Although Khan lost the 2013 general election to longtime rival Nawaz Sharif, his party became the third largest in the National Assembly. Naqvi’s star was also rising. His private equity firm was expanding and winning new investors. He became a regular fixture at World Economic Forum meetings in Davos.

In July 2017, Pakistan’s Supreme Court removed Sharif from office over corruption allegations. Khan won the election in July 2018. As prime minister he became increasingly critical of the west, praising Afghanistan’s Taliban when US forces withdrew in 2021, and visiting Vladimir Putin in Moscow on the day Russian forces invaded Ukraine in February.

The Election Commission of Pakistan has been investigating the funding of the PTI for more than seven years. In January, the ECP’s scrutiny committee issued a damning report in which it said the PTI received funding from foreign nationals and companies and accused it of under-reporting funds and concealing dozens of bank accounts. Wootton Cricket was named in the report, but Naqvi wasn’t identified as its owner.

In April, Khan stood down after losing a parliamentary vote of no confidence, triggered in part by rising inflation. He has accused the US of orchestrating the vote and is now attempting to stage a political return to contest a general election due to take place by October 2023.

That re-election effort means that although the Naqvi funding took place almost a decade ago, the controversy around it, and the final findings of the election commission, are likely to be at the forefront of Pakistan politics for some time.

While it has previously been reported that Naqvi funded Khan’s party, the ultimate source of the money has never before been disclosed. Wootton Cricket’s bank statement shows it received $1.3mn on March 14 2013 from Abraaj Investment Management Ltd, the fund management unit of Naqvi’s private equity firm, boosting the account’s previous balance of $5,431. Later the same day, $1.3mn was transferred from the account directly to a PTI bank account in Pakistan. Abraaj expensed the cost to a holding company through which it controlled K-Electric, the power provider to Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city.

A further $2mn flowed into the Wootton Cricket account in April 2013 from Sheikh Nahyan bin Mubarak al-Nahyan, a member of Abu Dhabi’s royal family, government minister and chair of Pakistan’s Bank Alfalah, according to the bank statement and a copy of the Swift transfer details.

Naqvi then exchanged emails with a colleague about transferring $1.2mn more to the PTI. Six days after the $2mn arrived in the Wootton Cricket bank account, Naqvi transferred $1.2mn from it to Pakistan in two instalments. Rafique Lakhani, the senior Abraaj executive responsible for managing cash flow, wrote in an email to Naqvi that the transfers were intended for the PTI. Sheikh Nahyan didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“Like other populists, Khan is made of Teflon,” says Uzair Younus, director of the Pakistan initiative at the Atlantic Council, a Washington-based research group. “But his opponents will try to use the foreign funding controversy to weaken the argument that he is not corrupt,” he adds, and to encourage the election commission to “punish him and his party”.

A useful ally

Naqvi, 62, was born into a Karachi business family. After studying at the London School of Economics he spent the 1990s working in Saudi Arabia and Dubai and started Abraaj in 2002, building it into an investment powerhouse. With offices in Dubai, London, New York and across Asia, Africa and Latin America, the company raised billions of dollars from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the US administration of Barack Obama, the British and French governments and other investors.

Well-connected, Naqvi liked to impress. John Kerry — a speaker at one Abraaj event — was approached by the company about working with it after he served as US secretary of state. Naqvi met Britain’s Prince Charles and was active in one of his charities, the British Asian Trust. He was a board member of the UN Global Compact, which advises the UN secretary-general, and sat alongside former Nissan chair Carlos Ghosn on the board of the Interpol Foundation, which raises funds for the global police organisation.

In Washington he was seen as a useful ally. The Obama administration pledged $150mn to an Abraaj fund investing in Middle Eastern companies: a press release said that the partnership would help turn the US president’s promise to improve economic relations with Islamic nations into a reality. Some even saw him as a possible future political leader in Pakistan, which he once described as “a country not known for transparency”, before adding that Abraaj “did everything by the book” during its control of K-Electric.

“We avoided every single point where you would have had to come into contact with government — even though you were a utility — and have to pay someone something,” he said.

K-Electric was Abraaj’s single largest investment. But as the private equity firm ran into financial difficulties in 2016, Naqvi struck a deal to sell control of the power company to Chinese state-controlled Shanghai Electric Power for $1.77bn. Political approval for the deal in Pakistan was important and Naqvi lobbied the governments of both Sharif and Khan for backing. In 2016, he authorised a $20mn payment for Pakistan politicians to gain their support, according to US public prosecutors who later charged him with fraud, theft and attempted bribery.

The payment was allegedly intended for Nawaz Sharif and his brother Shehbaz, who replaced Khan as prime minister in April. The brothers have denied any knowledge of the matter. In January 2017, Naqvi hosted a dinner for Nawaz Sharif at Davos. After Khan became prime minister, Naqvi met him. While in office Khan criticised officials for delaying the sale of K-Electric but the deal has still not been completed.

Abraaj collapsed in 2018 after investors including the Gates Foundation started investigating whether the company was misusing money in a fund intended to buy and build hospitals across Africa and Asia. Abraaj said it was managing assets of about $14bn at the time. In 2019, US prosecutors indicted Naqvi and five of his former colleagues. Two former Abraaj executives have since pleaded guilty. Naqvi denies the charges.

Naqvi was arrested at London’s Heathrow airport in April 2019 after returning from Pakistan and faces up to 291 years in jail if found guilty of the US charges. Khan’s telephone number was included on a list of contacts he handed to police — a fact mentioned by lawyers representing the US government during Naqvi’s extradition trial in London.

His appeal against extradition to the US is expected to conclude later this year. But he has had to pay £15mn for bail and has hefty ongoing legal expenses. Wootton Place was sold to a hedge fund manager in 2020 for £12.25mn. Naqvi and his lawyer did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Moving money around

In 2012 Khan visited Wootton Place. In a written response to questions from the FT, the former cricketer said he had gone to “a fundraising event which was attended by many PTI supporters”. Blofeld, the cricket commentator, recalls that Khan “was persuaded to take the field” at Wootton. “It was extraordinary to see how he still had the knack of bowling those fast inswingers,” he says.

Naqvi, a self-described cricket purist, provided the bats, balls, osteopaths, masseurs, food, accommodation and clothing. He literally wrote the rules for the matches. Ball tampering — banned in cricket — was permitted in matches at Wootton because “it is important to encourage innovation and experimentation in cricket, as what is considered illegal today may be de rigueur tomorrow,” Naqvi once wrote to guests.

It was a critical time for Khan to gather funds ahead of the election scheduled for May 2013, and Naqvi worked closely with other Pakistani businessmen to raise money for his campaign. The largest entry in Wootton Cricket’s bank account in the months before the election was the $2mn from Sheikh Nahyan, now the UAE’s minister for tolerance. He is also an investor in Pakistan.

After Lakhani, the Abraaj executive responsible for cash flow, told Naqvi in an email that the sheikh’s money had arrived, Naqvi replied that he should send “1.2 million to PTI”. In another email to Lakhani after the sheikh’s money entered the Wootton Cricket account Naqvi wrote: “do not tell anyone where funds are coming from, ie who is contributing”.

“Sure sir,” Lakhani responded. He wrote that he would transfer $1.2mn from Wootton Cricket to the PTI’s account in Pakistan. Then after considering sending the funds to the PTI via Naqvi’s personal account, Lakhani proposed sending the money in two instalments to a personal account for businessman Tariq Shafi in Karachi and an account for an entity called the Insaf Trust in Lahore. Although the ownership of the Insaf Trust is unclear, the emails state that the final destination was the PTI. “Don’t eff this up rafiq,” Naqvi wrote in another email.

On May 6 2013, Wootton Cricket transferred a total of $1.2mn to Shafi and the Insaf Trust. Lakhani wrote in an email to Naqvi that the transfers were for the PTI. Khan confirmed that Shafi donated to the PTI. “It is for Tariq Shafi to answer as to from where he received this money,” Khan said in response to the FT. Shafi didn’t respond to requests for comment.

‘Prohibited funding took place’

The ECP investigation into the funding of Khan’s party was triggered when Akbar S Babar, who helped establish the PTI, filed a complaint in December 2014. Although thousands of Pakistanis worldwide sent money for the PTI, Babar insists that “prohibited funding took place”.

In his written response, Khan said that neither he nor his party was aware of Abraaj providing $1.3mn through Wootton Cricket. He also said he was “not aware” of the PTI receiving any funds that originated from Sheikh Nahyan. “Arif Naqvi has given a statement which was filed before the Election Commission also, not denied by anyone, that the money came from donations during a cricket match and the money as collected by him was sent through his company Wootton Cricket,” Khan wrote.

Khan said he was waiting for the verdict of the election commission’s investigation. “It will not be appropriate to prejudge PTI.”

In its January report, the election commission said Wootton Cricket had transferred $2.12mn to the PTI but didn’t reveal the original source of the money. Naqvi has acknowledged his ownership of Wootton Cricket and denied any wrongdoing. In a statement, he told the election commission that: “I have not collected any fund from any person of non-Pakistani origin, company [public or private] or any other

The bank statement for Wootton Cricket tells a different story. It shows that Naqvi transferred three instalments directly to the PTI in 2013 adding up to a total of $2.12mn. The largest was the $1.3mn from Abraaj which company documents show was transferred to Wootton Cricket but charged to its holding company for K-Electric.

The impact of the scandal could yet hit Khan’s re-election ambitions. In July he renewed his call for an early poll after the PTI won a critical victory in by-elections in Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province. On Twitter, he called the Election Commission of Pakistan “totally biased”.

At the same time prime minister Shehbaz Sharif has urged the commission to publish its verdict in the PTI case, saying that the delays caused by political infighting had given Khan “a free pass despite his repeated & shameless attacks on state institutions”.

Yet the Atlantic Council’s Younus says that Khan’s loyal supporters won’t be moved whatever the outcome. They “do not and will not care. In fact, Khan may claim that the story is further evidence that foreign powers are leveraging global media to conspire against him.”

For Babar, who helped found the PTI, the controversy is proof that Khan has fallen short of the ideals they set out to champion in politics. “He had the opportunity of a lifetime and he blew it,” Babar says. “Our cause was reform, change — introduce the values in our politics that we espoused publicly.” Instead, he says, “[Khan’s] morality compass in a political sense went haywire”.

Monday 18 April 2022

Sunday 4 July 2021

Saturday 30 January 2021

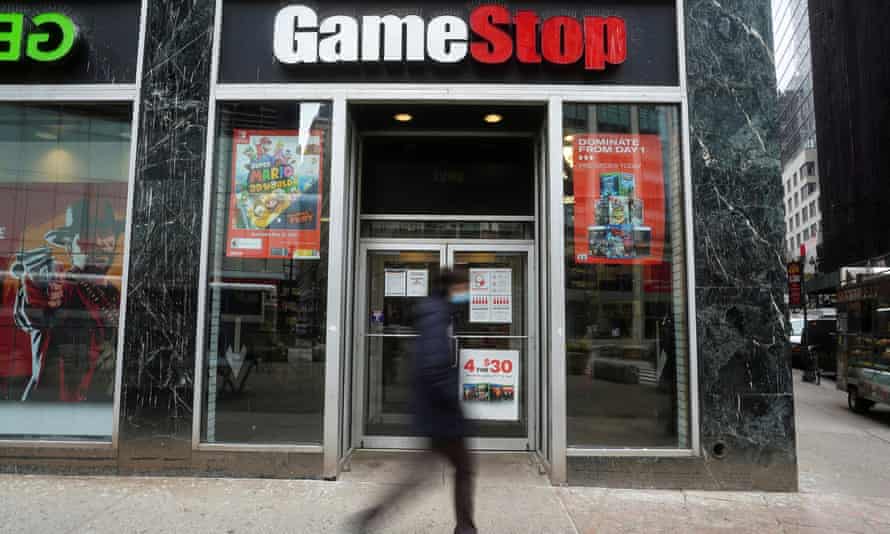

The GameStop affair is like tulip mania on steroids

Towards the end of 1636, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the Netherlands. The concept of a lockdown was not really established at the time, but merchant trade slowed to a trickle. Idle young men in the town of Haarlem gathered in taverns, and looked for amusement in one of the few commodities still trading – contracts for the delivery of flower bulbs the following spring. What ensued is often regarded as the first financial bubble in recorded history – the “tulip mania”.

Nearly 400 years later, something similar has happened in the US stock market. This week, the share price of a company called GameStop – an unexceptional retailer that appears to have been surprised and confused by the whole episode – became the battleground between some of the biggest names in finance and a few hundred bored (mostly) bros exchanging messages on the WallStreetBets forum, part of the sprawling discussion site Reddit.

The rubble is still bouncing in this particular episode, but the broad shape of what’s happened is not unfamiliar. Reasoning that a business model based on selling video game DVDs through shopping malls might not have very bright prospects, several of New York’s finest hedge funds bet against GameStop’s share price. The Reddit crowd appears to have decided that this was unfair and that they should fight back on behalf of gamers. They took the opposite side of the trade and pushed the price up, using derivatives and brokerage credit in surprisingly sophisticated ways to maximise their firepower.

To everyone’s surprise, the crowd won; the hedge funds’ risk management processes kicked in, and they were forced to buy back their negative positions, pushing the price even higher. But the stock exchanges have always frowned on this sort of concerted action, and on the use of leverage to manipulate the market. The sheer volume of orders had also grown well beyond the capacity of the small, fee-free brokerages favoured by the WallStreetBets crowd. Credit lines were pulled, accounts were frozen and the retail crowd were forced to sell; yesterday the price gave back a large proportion of its gains.

To people who know a lot about stock exchange regulation and securities settlement, this outcome was quite inevitable – it’s part of the reason why things like this don’t happen every day. To a lot of American Redditors, though, it was a surprising introduction to the complexity of financial markets, taking place in circumstances almost perfectly designed to convince them that the system is rigged for the benefit of big money.

Corners, bear raids and squeezes, in the industry jargon, have been around for as long as stock markets – in fact, as British hedge fund legend Paul Marshall points out in his book Ten and a Half Lessons From Experience something very similar happened last year at the start of the coronavirus lockdown, centred on a suddenly unemployed sports bookmaker called Dave Portnoy. But the GameStop affair exhibits some surprising new features.

Most importantly, it was a largely self-organising phenomenon. For most of stock market history, orchestrating a pool of people to manipulate markets has been something only the most skilful could achieve. Some of the finest buildings in New York were erected on the proceeds of this rare talent, before it was made illegal. The idea that such a pool could coalesce so quickly and without any obvious sign of a single controlling mind is brand new and ought to worry us a bit.

And although some of the claims made by contributors to WallStreetBets that they represent the masses aren’t very convincing – although small by hedge fund standards, many of them appear to have five-figure sums to invest – it’s unfamiliar to say the least to see a pool motivated by rage or other emotions as opposed to the straightforward desire to make money. Just as air traffic regulation is based on the assumption that the planes are trying not to crash into one another, financial regulation is based on the assumption that people are trying to make money for themselves, not to destroy it for other people.

When I think about market regulation, I’m always reminded of a saying of Édouard Herriot, the former mayor of Lyon. He said that local government was like an andouillette sausage; it had to stink a little bit of shit, but not too much. Financial markets aren’t video games, they aren’t democratic and small investors aren’t the backbone of capitalism. They’re nasty places with extremely complicated rules, which only work to the extent that the people involved in them trust one another. Speculation is genuinely necessary on a stock market – without it, you could be waiting days for someone to take up your offer when you wanted to buy or sell shares. But it’s a necessary evil, and it needs to be limited. It’s a shame that the Redditors found this out the hard way.

Saturday 8 June 2019

Bright star to black hole: the rise and fall of fund manager Neil Woodford

He was, the BBC declared in 2015, “the man who can’t stop making money”. He was the rock star of pensions and fund management, awarded a CBE for his services to the economy. But now, since Neil Woodford stopped investors from withdrawing their own money from his flagship fund, he is in the spotlight for all the wrong reasons.

His Woodford Equity Income Fund holds the pension savings and investments of tens of thousands of people. But it has been performing so badly that investors were withdrawing money at the rate of £10m a day.

-----Also read

It can be Hard to tell Luck from Judgment

-----

Last week, after 23 consecutive months in which withdrawals from the fund had been greater than the new money coming in, Woodford found he couldn’t realise cash quickly enough to meet the withdrawal requests – at least at a decent price. He closed the fund to withdrawals, leaving legions of investors angry and in limbo for 28 days.

In a YouTube video he posted on Wednesday to finally apologise to investors, he looked anything but the archetypal City fund manager, with his close-cropped hair and trademark casual jumper rather than suit and tie. In the video, filmed at his fund’s headquarters on an industrial estate near Oxford, Woodford said: “I’m extremely sorry that we’ve had to take this decision. We understand our investors’ frustration. All I can say in response to that is that this decision was motivated by your interests.”

Woodford said he had been forced to “gate” the fund because so many big investors were trying to pull money out that he wasn’t able to meet the demand. His funds hold unusually big stakes in smaller and early stage unlisted companies, which are hard to sell quickly.

The final straw had been Kent county council pension fund’s request to take out its £263m holding. The trustees of Kent’s pension fund – who had been trying to stem the losses Woodford had racked up for its 110,000 members – decided to pull out when it emerged at the end of last month that the flagship fund had shrunk by £560m to £3.77bn in just four weeks. At its peak the fund was worth more than £10bn.

Of the £560m lost, just under £190m was made up of withdrawals. The rest – more than £370m – represented yet further declines in the value of the investments held in the fund, which at the end of April was made up of stakes in 101 companies ranging from housebuilders such as Barratt Developments and Taylor Wimpey to logistics business Eddie Stobart and a large number of esoteric healthcare firms.

Under EU rules aimed at ensuring that funds which hold unquoted – and therefore potentially hard-to-sell – shares can retain their stability, these shares are permitted to make up no more than 10% of the portfolio. Woodford got around those rules, quite legally, by putting some of them into his separate, quoted Patient Capital investment trust – and taking Patient Capital shares into the main fund. He also listed some of them of the Guernsey stock exchange.

But the Kent fund had left it just too late: instead of getting its cash back, its request triggered Woodford’s suspension of trading in the fund.

The video apology, in which Woodford set and answered his own questions, followed months during which he had been dismissing the concerns of investors and financial experts about his fund’s prolonged poor performance.

In February, his Woodford Equity Income Fund was listed for the first time on a “Spot the Dog” list compiled by Bestinvest, which highlights underperforming “dog” funds. Bestinvest criticised some of his worst investments and described the fund as “a Great Dane-sized” new entrant to its list.

Just a few weeks later, Woodford told the Financial Times that the investors who were pulling out were making “appallingly bad decisions”, influenced by “a mountain of fake information and fake analysis” that “pisses me off”.

Neil Woodford apologises to investors in a still from his YouTube video last week. Photograph: Woodford Investment Management/PA

In December 2017 he said in an interview that they key to successful investing was to “have a sufficiently strong arrogant gene to back your judgment, back your conviction”.

That arrogance is now provoking widespread anger, not just from his investors but also among other fund managers, who say Woodford has tarred the whole industry with the same loss-making brush.

Last Wednesday the Financial Conduct Authority, the City’s watchdog, said it was considering a formal investigation into the fund, and the following day, Bank of England governor Mark Carney told an audience in Tokyo that funds such as Woodford’s (although he died not name him) needed closer scrutiny to lessen the risk of fire sales triggering market disruption. The Bank, he said, would start stress-testing funds to ensure they couldn’t threaten a system-wide crisis.

This is a staggering fall from grace for Woodford, who had been one of the UK’s very best and most reliable stock pickers. Anyone who invested £10,000 at the start of his quarter-of-a-century career at Invesco Perpetual would have seen their money grow to almost £250,000 by the time he left.

Mark Dampier, director of research at stockbroker Hargreaves Lansdown, declared in 2015 that Woodford was “arguably the best fund manager of his generation”. Just weeks ago, despite the growing cloud surrounding Woodford, Hargreaves told its clients “we retain our conviction in him to deliver excellent long-term performance” and reminded them that he had “built his career by investing against the herd” and “shown an ability to get the big calls right”.

Hargreaves’s customers had £2bn invested with Woodford at the end of March – roughly a fifth of all the money in his three big funds.

Only when the fund was gated did Hargreaves, which has heavily promoted Woodford at discounted fees, finally drop Woodford Equity Income from its influential “Wealth 50” list of favourite funds, which it marketed to its more than a million clients.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Bank of England governor Mark Carney has suggested that funds such as Woodford’s need more scrutiny. Photograph: Hannah McKay/Reuters

Asked if he regretted his support for Woodford and the controversial discount fee structure, Dampier said: “Our aim is to enable our clients to choose the best-in-class funds at lower fees. Our favourite fund choices have, for the most part, beaten their sector averages and benchmarks. Not every fund has, and we share our clients’ disappointment and frustration when they don’t.”

Other big backers have also deserted Woodford. St James’s Place last week took its clients’ £3.5bn to another manager. On Thursday another supporter, Openworks, did the same with its £330m.

Woodford fell into fund management by accident. He had never even heard of the business until he rocked up in London in the 1980s, sleeping on his brother’s floor while looking for a job. He had left school wanting to fly fighter jets but couldn’t pass the RAF’s aptitude test, and instead read agricultural economics at the University of Exeter.

In 1988 he joined Invesco Perpetual and built a reputation as a brilliant contrarian investor. When others piled into dotcom shares at the turn of the century, he decided against, and backed more traditional companies. He made huge gains when the dotcom crash came. He eschewed banking stocks before the financial crisis – and avoided that crash too.

He held big stakes in giant companies, whose chief executives needed to retain his support. In 2012 his criticism of AstraZeneca chief executive David Brennan was widely regarded to have cost Brennan his job, and his criticism of BAE’s attempted £28bn merger with Airbus was seen as one of the reasons the deal collapsed.

In 2014, feeling that he had outgrown Invesco Perpetual, where he personally managed some £25bn of funds, he set up his own firm, Woodford Investment Management. Within two weeks of launching, he had raised £1.6bn, a UK record, and this quickly grew to £16bn. In its first year, his flagship fund made a 16% return and Woodford, a devotee of veteran US investor Warren Buffett, was called the “Oracle of Oxford”.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Woodford is a keen student of the US investor Warren Buffett. Photograph: Andrew Harnik/AP

But since then things have turned sour. Over the past four years, investors in Woodford Equity Income have collected a return of less than 1% – compared with 29% for the market as a whole. Over that same four-year period, Woodford has paid himself some £63m.

In the 2017-18 financial year alone, which was a dreadful period for his funds, Woodford Investment Management paid a £36.5m dividend to a company called Woodford Capital. Woodford holds 65% of that firm, and his business partner Craig Newman has the remaining 35%.

Woodford, who has spoken out against the huge bonuses awarded to other fund managers, and to the bosses of companies he has invested in, declined to answer any questions about his own pay, or to elaborate, beyond his YouTube video, on the fund’s tricky situation.

The firm’s public relations officer asked the Observer to point out that Woodford had donated some of his pay to charity. But he was unable to state how much money had been donated, or to which causes. The PR person declined to comment when asked whether Woodford would consider pumping any of his personal millions back into the fund.

Those who know Woodford say he is “decidedly unflashy” and that it is “difficult to fathom where all that money goes”. Well, a lot of it appears to go on horses. He and his wife Madelaine have a few dozen top showjumpers training at a vast equestrian complex near their home in the Cotswolds.

The house, near Tetbury, was built on land the Woodfords bought for nearly £14m in 2013. They moved to the Cotswolds after a planning application to construct a dressage arena and 28-horse stabling block near their previous estate, in Buckinghamshire, was rejected following a row with neighbours. One of those neighbours, the BBC’s Jeremy Paxman, described Woodford’s planned addition as “enormous, unsightly and environmentally unfriendly”.

The Tetbury venue, however, got the planners’ green light and includes a full-size manège (dressage arena). Woodford, who came to the sport only after meeting Madelaine – a keen rider whom he married in 2015 – has put in the hours at the manège and now often takes part in eventing competitions on a bay gelding called Willows Spunky.

Woodford’s other passions are fast cars and racing bicycles. He starts up the Porsche at 5am every weekday to drive to his fund’s minimalist offices on an industrial estate in Cowley, Oxford. At weekends he drives it down to the couple’s £6.3m glass-walled holiday home in Salcombe, Devon.

Woodford’s huge pay and luxury lifestyle haven’t gone unnoticed by his investors, many of whom are relying on him to be a safe pair of hands and to increase the value of their retirement or rainy day fund.

A comment on his YouTube video, by someone with the username Platoreads: “Arrogance, Incompetence, Complacency and greed: your name is Woodford! You have failed, Neil. Return the funds to your investors (including that £37m bonus you pocketed this year despite a disastrous performance in all three funds).”

Luke Hilyard of the High Pay Centre said: “This particular instance of an investor making tens of millions while losing money for ordinary savers raises questions about the governance of the funds and platforms channelling other people’s money into Woodford’s fund, and the regulatory oversight of the process.

“The case is also a microcosm of our wider business culture and economic system, where superstar managers in investment, banking, retail, commodities and other industries have been treated like gods and rewarded accordingly, yet ultimately have shown themselves to be highly fallible mortals whose success was always partly contingent on timing and luck.”

Woodford, who made his name at Invesco by backing big companies, but then switched to a new strategy of investing in smaller and unquoted companies in his own funds, has now pledged to change direction.

In his video he said he would now be targeting bigger companies, especially FTSE 100 stocks – even though only a few weeks ago he was insisting that his approach was the correct one and that the best investment opportunities were “absolutely not” in large companies.

Big bad bets

Woodford bought big stakes in many companies that performed very poorly. They include:

• Kier (construction) -74% in 12 months; Woodford funds own 20%

• Circassia (biotech) -74%; Woodford owns 28.5%

• Prothena (biotech) -36%; Woodford owns 29.9%

• Stobart Group -46%; Woodford owns 18.8%

• Redde (support services) -39%; Woodford owns 28%

• Allied Minds (technology) -31%; Woodford owns 27%

• Spire Healthcare -51%; Woodford owns 5%

• Utilitywise, energy broker that collapsed in Feb 2019; Woodford owned 29%

What Woodford investors say:

“I invested £60,000 three years ago and have lost over 20%. Luckily I sold nearly half my investment the week before the fund closed. I’m going to hold my remaining units until after Brexit as a high-risk bet.”

Simon, 51, Brighton

“I‘m getting married on 10 August and we’ve been saving for over two years. My final bill to the venue and suppliers is due at the start of July. If I can’t withdraw my money I’m going to be looking to beg, borrow or steal until I can get it released.”

James M, 28, Newcastle

“I inherited some money, and chose on a stocks and shares Isa, following suggestions from Hargreaves Lansdown, then watched the value dwindle. On 31 May I decided to take the hit and sell. The deal was shown as “pending” until Wednesday morning, but that disappeared and I was told I wouldn’t be able to sell my units. I don’t think I’ll be getting much back when trading opens again.”

Sally Williams, 53, London

Tuesday 28 March 2017

Saffron storm, hard cash

A young man described himself as a dejected Muslim, and punctured the sharp analysis that was under way about the Uttar Pradesh defeat. The venue was a well-appointed seminar room at the India International Centre. Why don’t we show our outrage like they do in America, the young Muslim wanted to know. People in America are out on the streets fighting for the refugees, Latinos, Muslims, blacks, everyone. One US citizen was shot trying to protect an Indian victim of racial assault. Why are Indian opponents of Hindutva so full of wisdom and analysis but few, barring angry students in the universities, take to the streets?

It’s not that people are not fighting injustices. From Bastar to Indian Kashmir, from Manipur to Manesar, peasants, workers, college students, tribespeople, Dalits; they are fighting back. But they are vulnerable without a groundswell of mass support like we see in other countries.

Off and on, political parties are capable of expressing outrage. A heartbreaking scene in parliament is to see Congress MPs screaming their lungs out with rage, but that’s usually when Sonia Gandhi is attacked or Rahul Gandhi belittled. Yet there is no hope of stopping the Hindutva march without accepting the Congress as a pivot to defeat the Modi-Yogi party in 2019.

It’s a given. The slaughterhouses may or may not open any time soon, but an opposition win in 2019 is easier to foresee. It could be a pyrrhic victory, the way the dice is loaded, but it is the only way. Will the Congress join the battle without pushing itself as the natural claimant to power? Without humility, we may not be able to address the young man’s dejection.

Like it or not, there is no other opposition party with the reach of the Congress, even today. Should we be saddled with a party that rises to its feet to protect its leaders — which it should — but has lost the habit of marching against the insults and torture that large sections of Indians endure daily?

A common and valid fear is that the party is vulnerable before the IOUs its satraps may have signed with big league traders, who drive politics in India today.

If religious fascism is staring down India’s throat, there’s someone financing it.

The Congress needs to ask itself bluntly: who chose Mr Modi as prime minister? It was the same people that chose Manmohan Singh before him. The fact is that India has come to be ruled by traders, though they have neither the vision nor the capacity to industrialise or modernise this country of 1.5 billion. Their fabled appetite for inflicting bad loans on the state exchequer is legendary, though they have seldom measured up to Nehru’s maligned public sector to build any core industry. (Bringing spectrum machines from Europe and mobile phones from China for more and more people to watch mediocre reality shows is neither modernisation nor industrialisation.)

The traders have thrived by funding ruling parties and keeping their options open with the opposition when necessary. It’s like placing casino chips on the roulette table, which is what they have turned a once robust democracy into. If there’s religious fascism staring down India’s throat, there’s someone financing it.

The newspapers won’t tell you all that. The traders own the papers. The umbilical cord between religious regression and traders has been well established in a fabulous book on the Gita Press by a fellow journalist; same with TV.

Nehru wasn’t terribly impressed with them. He fired his finance minister for flirting with their ilk. Indira Gandhi did one better. She installed socialism as a talisman against private profiteers in the preamble of the constitution. They hated her for that. The older Indian literature (Premchand) and cinema were quite a lot about their shady reality — Mother India, Foot Path, Do Bigha Zamin, Shree 420, to name a few.

At the Congress centenary in Mumbai, Rajiv Gandhi called out the ‘moneybags’ riding the backs of party workers. They retaliated through his closest coterie to smear him with the Bofors refuse. The first move against Hindutva’s financiers will be an uphill journey. The IOUs will come into play.

For that, the Congress must evict the agents of the moneybags known to surround its leadership. But they’re not the only reality the Congress must discard. It has to rid itself of ‘soft Hindutva’ completely, and it absolutely must stop indulging regressive Muslim clerics as a vote bank.

For a start, the West Bengal, Karnataka, and Delhi assemblies will need every opposition member’s support in the coming days. The most laughable of the cases will be summoned against the unimpeachable Arvind Kejriwal, a bête noire for the traders, whose hanky-panky he excels in exposing.

For better or worse, it is the Congress that still holds the key to 2019. Even in the post-emergency rout, the party kept a vote share of 41 per cent. And after the 2014 shock, its vote has grown, not decreased.

While everyone needs to think about 2019, the left faces a more daunting challenge. It knows that the Modi-Yogi party does not enjoy a majority of Indian votes. However, the majority includes Mamata Banerjee, who says she wants to join hands with the left against the BJP. Others are Lalu Yadav, Nitish Kumar, Arvind Kejriwal, Mayawati, Akhilesh Yadav, most of the Dravida parties and, above all, the Congress. The left has inflicted self-harm by putting up candidates against all these opponents of the BJP — in Bihar, in Uttar Pradesh, in Delhi. In West Bengal and Kerala, can it see eye to eye with its anti-BJP rivals?

As the keystone in the needed coalition, the left must drastically tweak its politics. It alone has the ability to lift the profile of the Indian ideology, which is still Nehruvian at its core, as the worried man at the Indian International Centre will be pleased to note.

Thursday 23 March 2017

The inside story of the Tory election scandal

A few hours after dawn on 8 May 2015, the morning after his unexpected victory in the general election, David Cameron delivered a celebratory speech to the jubilant staff of Conservative campaign headquarters, at 4 Matthew Parker Street, Westminster. “I’m not an old man but I remember casting a vote in 1987 and that was a great victory,” he said. “I remember 2010, achieving that dream of getting Labour out and getting the Tories back in, and that was amazing. But I think this is the sweetest victory of them all.”

The assembled Tory campaign staffers cheered and whistled as Cameron declared: “We are on the brink of something so exciting.” The election result would indeed change British politics, although not in the way that Cameron intended: the obliteration of the Conservatives’ Liberal Democrat coalition partners cleared the way for the referendum that set Britain on a path to leave the EU and ended Cameron’s political career. As a result, Theresa May is now the prime minister, while Cameron is on a speaking tour of US universities and George Osborne is moonlighting as a newspaper editor.

Until recently, Britain thought it knew how the Conservative party had defied expectations to win the election. After the initial shock that predictions of a hung parliament had proved incorrect, a new narrative was soon established. Commentators explained that the Tories had prevailed by successfully emphasising the threat of a Labour coalition with the SNP and deploying the “pumped-up” prime minister for a spurt of decisive last-minute campaigning. Several newspapers reported that the Tories had spent less to win their 12-seat majority in 2015 than they did to win 24 fewer seats in 2010.

In truth, the victorious Conservative campaign was the most complex ever mounted in Britain, run by two of the world’s most successful campaign consultants. Warehouses of telephone pollsters were put to work for a year before the election, their task to track the views of undecided voters in key marginal seats. The party also distributed thousands of detailed surveys to voters in marginals, and merged all this polling data with information from electoral rolls and commercial market research to produce the most comprehensive picture yet of who might be persuaded to vote Conservative.

Armed with an unprecedented level of detail, the Conservatives began distributing leaflets and letters that directly addressed the hopes and fears of their target voters. And in the final weeks of the campaign, shock troops of volunteers were dispatched to the doorsteps of undecided voters with a mission to persuade and cajole on the party’s behalf. In the most high-profile fight, an elite squad of strategists moved from the London HQ to Kent, where the Ukip leader Nigel Farage was making his bid for parliament.

If the sophistication of the 2015 campaign was not widely known, that was by design: the Conservative Home website, a meeting place for party loyalists, called the victory a “stealth win”. But over the last few months, another story has emerged – an account that is told in a paper trail of hotel bills, emails and witness statements that has led to a year-long investigation by the Electoral Commission and the police.

The startling evidence, first unearthed by Channel 4 News and confirmed in a condemnatory report released last week by the Electoral Commission – the independent body that oversees election law and regulates political finance in the UK – suggests that the Conservative party gained an advantage by breaching election spending laws during the 2015 election. This allowed the party to send its most dedicated volunteers into key seats, in which data had identified specific voters whose turnout could swing the contest. Some of this spending was not properly declared, and some of it was entirely off the books. The sums involved are deceptively small, but the impact may have been decisive.

At present, up to 20 sitting Conservative MPs are the subject of criminal investigation by 16 police forces. If any of the candidates are charged and found guilty of an election offence, they could be barred from political office for three years or spend up to a year in prison. The whole case is unprecedented: this is the largest number of MPs ever to be investigated for violations of electoral law. In the past, cases of alleged election fraud have usually focused on a single MP. This time, there are so many cases that police forces across England have taken the unusual step of coordinating their investigations.

The release of last week’s 38-page Electoral Commission report produced a minor political earthquake: as a result of the biggest investigation the commission has ever undertaken, it levied its largest-ever fine against the Conservative party and referred the case of the party’s treasurer, Simon Day, to the Metropolitan police for further criminal investigation. “There was a realistic prospect,” the report said, that the undeclared spending by the party had “enabled its candidates to gain a financial advantage over opponents.”

The party’s response to the report has been dismissive from the very start. During their investigation, the Electoral Commission was forced to file papers with the high court, demanding that the Conservative party disclose information about its election campaign, after the party had failed to fully comply with their requests for information for three months. Since the report was published, Conservative ministers and spokesmen have pointed out that the commission found only “a series of administrative errors” and that other parties have been fined for their activity in the 2015 election too. Conservatives also say that the missing money identified by the commission represents just 0.6% of the total spent by the party during the 2015 election.

It is true that the sums involved in this case are small: the Electoral Commission’s highest-ever fine turns out to be just £70,000, and it has been applied to punish undeclared and misdeclared Conservative spending totalling just £250,000. Most reports on the commission’s findings have echoed this defence, allowing that some criminal charges may indeed be filed, while overlooking the impact of the overspending on the result.

But British elections are designed to be cheap. Laws that date back to the 1880s limit campaign spending precisely so that people of all backgrounds, and not only the wealthy, have a fair chance to compete for votes. And if that egalitarian principle enhances our political culture, it has another less obvious consequence: even small sums of additional, illegal money, if shrewdly spent, can make a huge difference to results.

Thanks to the Electoral Commission report, we now know that some of the Conservative party’s central spending did benefit MPs in the tightest races, but it was not declared. It is possible even that this money helped to secure the victories from which the Conservative majority was derived. Slowly, a chilling prospect emerges that British politics, our relationship with Europe and the future of our economy, were all transformed following a contest that wasn’t a fair fight.

The Conservatives’ election worries were never financial. By the end of 2014, newspapers reported that the party had raised substantially more money than its rivals, assembling a £78m “war chest” that would allow it to “funnel huge amounts of cash into key seats”, according to the Observer. The campaign would be constrained only by two factors: the legal spending limits for each candidate and the number of volunteers the party could recruit to take its message to voters.

In fact, the scandal in which so many MPs now find themselves embroiled concerns precisely those limits. The spending that has been found to be in violation by the Electoral Commission was used to bring Conservative campaigners into the tightest marginal election battles. Separately, multiple police investigations are examining whether individual candidates and their election agents broke the law.

It is difficult to understand the election expenses scandal without understanding the election strategy that had been unveiled three years before the vote. At a closed session on the first day of the 2012 Conservative conference, the party’s campaign director, Stephen Gilbert, laid out a plan that would come to be known as the 40/40 strategy. For the 2015 election, the party would focus single-mindedly on holding 40 marginal seats and winning another 40. Candidates for these seats would be selected early, and full-time campaign managers – heavily subsidised by Conservative campaign headquarters (CCHQ) – would be appointed in every 40/40 seat.

The 40/40 campaign would be centrally controlled and would require two ingredients. The first was detailed information about every potential Conservative voter in each of the marginal seats. The second was a field team capable of making contact with them and persuading them to vote Tory.

To put the plan into action, the party turned to two men who have helped reshape the way elections are fought. The first, the Australian political strategist Lynton Crosby, had overseen the Tories’ 2005 general election campaign and Boris Johnson’s two victories in London mayoral elections.

Crosby’s notoriety made him the subject of considerable press attention – but the second man behind the Conservative campaign may have been even more important. This was the American strategist Jim Messina, who was hired as a strategy adviser in August 2013. Senior Conservative staff had been awestruck by Barack Obama’s comfortable victories in the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, crediting their relentless focus on data to Messina.

British elections are designed to be cheap: even small sums of additional money can make a huge difference to results

Using vast databases, commercial market research, complex questionnaires and phone banks, Messina had been able to map the fears and desires of swing voters, and design highly personalised messaging that would appeal to them. The Conservatives hired him to perform the same magic in Britain. To do so, Messina used commercial call centres to track the views of between 1,000 and 2,000 voters in all 80 of the seats targeted by the 40/40 strategy.

This data was crucial to the Conservative campaign: it determined which voters the party needed to contact and which messages they would hear. This began with direct mail – personally addressed to voters in each target seat, who were divided into 40 different categories, with a slightly different message for each one.

But the big-data strategy requires more than leaflets: once you have identified the voters who might be persuaded to switch, and fine-tuned what message to give them, you have to send campaigners to actually knock on their doors and urge them to go to the polls on election day. This requires an army of volunteers, spread across dozens of constituencies. It fell to the party’s co-chairman, Grant Shapps, to establish the necessary volunteer outreach program, which was dubbed Team2015.

Shapps had begun sending out recruitment emails to the party’s mailing list in the summer of 2013, hoping to build a centrally controlled base of activists who could be deployed to marginal constituencies. CCHQ demanded that Team2015 coordinators be established in every swing seat. It was an uphill struggle. Rallying enthusiastic volunteers to David Cameron’s cause turned out to be a harder task than attracting Obama supporters had been.

Conservative membership had been in long-term decline from a peak of 2.8 million in 1952. Under David Cameron’s leadership, the number of party members had further depleted, halving to fewer than 150,000. Those remaining members tended to be older and less active – not the dynamic door-knocking volunteers that Team2015 wanted to recruit. While some local Conservative associations reported new members, most described numbers as “hit and miss”. One seat’s early Team2015 report records: “[Team2015] invited to party with MP – no one turned up!”

In some marginal seats, Team2015 was almost nonexistent. One campaign manager recalls: “Trying to get members to volunteer was practically impossible, so Team2015 volunteers were even worse. People would put their names down, generally via CCHQ, who would then pass the person’s details to the local campaign manager but, in my case, when I tried to contact them I never got any volunteers.”

As the election drew nearer, Shapps made upbeat reports on the growing volunteer force. But, according to Conservative Home, the party’s records indicate that only about 15,000 people ever turned up to campaign, and fewer than that did so regularly.

There was, however, another team at work. Unsupervised by CCHQ to start with, it would later be adopted as a critical element in the party’s “ground war” since – unlike Team2015 – it had managed to deliver platoons of committed Conservative activists to the places that needed them most in a series of crucial byelections the year before. It was called RoadTrip.

RoadTrip2015 was the brainchild of Mark Clarke, who would become infamous after the election as “the Tatler Tory”, pilloried in the press over accusations that he bullied a young Conservative who later killed himself, and made unwanted sexual advances towards female members of the party – allegations he has always denied. But in 2014, as a failed parliamentary candidate desperate to get back into the party’s good graces, he launched a grassroots volunteer scheme that sent party members into marginal seats to distribute leaflets, knock on doors, and work the voters.

RoadTrip2015’s work began with a March 2014 trip to Cannock Chase, a West Midlands Labour marginal where 50 volunteers battled through a hailstorm to the doorsteps of swing voters. In the months that followed there were trips to Harlow, Chester and Cheadle. In Enfield, Team2015 marshalled 130 volunteers and party co-chair Grant Shapps attended too. But what put the scheme on the map, and drew the admiration of Conservative commentators and MPs, was the Newark bylection in early June 2014.

On 31 May, the Saturday before the byelection, Clarke successfully marshalled 500 volunteers to Nottinghamshire to campaign for the Conservative candidate, Robert Jenrick. Clarke posted his invitation across social media and on the Conservative Home website: “Join us, Grant Shapps and the hundreds of people signed up this Saturday to come to Newark. Afterwards, join Eric Pickles for the inaugural annual RoadTrip2015 dinner (a free curry) in nearby Nottingham. We will take care of your travel from cities like London, Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol and York.”

The Newark campaign was the first major stress test for the Conservatives’ parliamentary election team. By polling day, 5 June, they were feeling intense pressure from Ukip, which had triumphed in the European elections two weeks earlier – showing they were more than capable of stealing support away from the Conservatives.

Before Clarke’s RoadTrip arrived in Newark, a small team of senior Conservative staff – including Stephen Gilbert and a “campaign specialist” named Marion Little – had quietly taken position on the outskirts of the town at the Kelham House country manor hotel. In Newark itself, many more junior party employees – some of them campaign managers from other 40/40 seats – worked from temporary offices during the day and, at night, stayed in a Premier Inn.

The well-resourced Tory campaign turned out to be decisive and Robert Jenrick was returned with a 7,403 majority – rather smaller than his predecessor, but still substantial. But, on the evening of the count an exasperated Nigel Farage, interviewed by Channel 4 News political correspondent Michael Crick, raised the first concerns about Conservative election expenses – which, he suggested, might have breached the £100,000 limit for campaign spending in a byelection.

“Given the number of paid professional people from the Conservative party here, it is difficult to believe that their returns are going to come in below the figure,” Farage said, referring to the documents every candidate must file to detail their campaign costs. “I’d love to see what their returns are. Because it seems to me the scale of the campaign they fought here is so vast … There will certainly be some questions.”

The rules in a byelection contest are simple. All costs incurred in promoting the candidate in parliamentary elections – advertising, staff costs, unsolicited leaflets and letters, transport for campaigners, hotels that volunteers do not pay for themselves, and administrative costs such as phone bills and stationery – must be declared. Deliberate overspending can be a criminal offence, and it may also lead to an election being declared void.

Robert Jenrick’s campaign in Newark had declared expenses of £96,191. But the Electoral Commission later found that his return did not include the hotel bills for 54 nights of accommodation for senior Conservative staff, or 125 nights of hotel rooms for junior Conservative staff at the Premier Inn. Those costs totalled more than £10,000; had they been declared, the campaign would have breached the spending limits. Farage had been correct. (When questioned by Channel 4 News in 2016, Jenrick denied all wrongdoing. In response to questions about by-election hotel expenses, the party responded that “all byelection spending has been correctly recorded in accordance with the law”.)

At the time, however, these details remained unknown – and Channel 4 News reporters did not discover the undeclared hotel bills until long after the one-year time limit for the imnvestigation and prosecution of election crimes had passed. As a result, there was little attention to increasing Conservative spending in two more crucial byelections.

In October 2014, another huge team of Conservatives descended on Clacton-on-Sea, where Douglas Carswell had defected from the Conservatives to stand as a Ukip candidate. Again, hotels were booked for visiting campaign staff, and a return of £84,049 was filed – which did not mention all the party’s hotel costs of 290 nights at the Lifehouse Spa & Hotel, and 71 nights at the Premier Inn, worth at least £22,000. Had they been declared, the overspending would have been more than £8,000.

In Rochester and Strood, where the defection to Ukip of yet another Tory candidate, Mark Reckless, prompted another byelection in November 2014, the Conservatives could have breached the spending limit by a far larger amount – more than £51,096. As detailed in the Electoral Commission report, their candidate did not declare hotel costs of at least £54,304 against expenses of £96,793. The Conservatives still lost both contests. (Neither of the Conservative candidates responded to requests for comment. The party replied on their behalf that all spending was filed in accordance with the law.)

In these byelections, RoadTrip2015 – which was now supported by CCHQ and endorsed by Shapps – became an increasingly important influence. When the campaign launched a Facebook page advertising for a “Clacton Volunteer Force”, 1,300 people signed up to take part. In Rochester and Strood, it offered volunteers who turned out on Saturday 8 November “FREE transport there and back, FREE drinks and access to the FREE RoadTrip2015 Disraeli Dinner with a very special guest speaker!” The guest speaker was Theresa May, who was filmed celebrating with volunteers. She said: “What you do matters so much because, although what the politicians do has got a role to play, in terms of election campaigning, it’s the people who go out on the doorsteps, who knock on those doors, who make those telephone calls, who put those leaflets through the door, that make a real difference to the results we have.”

By the time of the 2015 general election, the tactics that the party had used to saturate all three byelection constituencies with activists and workers would all come together: there would be more buses of volunteers, more undeclared hotel bookings, and more senior advisers moved out of London into crucial seats. But this time, it would be discovered.

Today, two pieces of rather antiquated legislation exist to tame the influence of money on our elections. The first law governs spending by constituency candidates in the run-up to a general election during two time periods: the “long campaign” runs from about six months before polling day until parliament is dissolved; what follows is the “short campaign”, a final frenzied push for votes that lasted for 38 days in 2015.

The spending limits in each period are tight, with exact values depending on the type of constituency (borough or county) and the number of voters. For the “long campaign” in 2015, the totals were typically around £35,000 to £45,000. While in the short campaign, the most crucial campaign period, the limits were tighter still, set at £8,700 plus 6p or 9p per elector, giving a limit of around £10,000 to £16,000.

The limits are low, theoretically allowing as many people as possible to mount a viable campaign for election. Any costs incurred promoting the candidate in the constituency – from advertising, administration and public meetings, to party-paid transport for campaigners, staff costs and accommodation – must be honestly declared. At the end of the campaign, every penny spent must be declared in an official spending return submitted soon after the end of the campaign. Each spending return includes a declaration that certifies it is “complete and accurate … as required by law”. This must be signed by both the candidate and their election agent – a member of the local party that they appoint to manage their spending. Failing to declare spending, and spending over the limit, are criminal offences.

The second election spending law applies to political parties, and sets much higher limits for their spending on national campaigning during a specified period – roughly a year – before the election. The precise limit is derived by multiplying the number of constituencies being contested by £30,000. For the Conservatives in 2015, this gave the party a national limit of £18.9m to spend promoting David Cameron and his plan for the country through advertisements, billboards and direct mail. As it turned out, the party ended up declaring a figure well below the limit – around £15.6m. It is the responsibility of the national party treasurers to ensure that these national returns are correct, and again they commit an offence if they are found not to be.

Of course, the existence of two different laws setting out two different spending limits – one for local spending and one for national spending – is a source of potential confusion. In the real world of campaigning, there are bound to be expenses that do not fit neatly into one category or the other. For example, leaflets may contain a national message on one page – promoting the party’s leader or policies – and a local message, from the constituency candidate, on another page. When this happens, both the party and the candidates are required to make an “honest assessment”, in the words of law, about how much of the cost of the leaflet should be declared on both returns, before “splitting” the value accordingly. To aid transparency, election material must, by law, carry an “imprint” that shows whether it was produced for the local candidate or for the national campaign.

But the presence of two separate spending laws also presents an opportunity for abuse. Much of the scandal surrounding the Conservative party’s 2015 election spending relates to evidence that suggests spending declared as “national” – where limits are much higher – was, in reality, used to promote local candidates, who face much tighter spending limits.

In fact, it is the enormous difference between the national limits, in the millions, and the local limits, in the tens of thousands, that makes these allegations so significant. Even small amounts of candidate overspending – easily buried in the multimillion-pound national accounts – could have a significant impact on a local campaign, and even shift the result.

Following Ukip’s triumph in the Clacton and Rochester byelections in late 2014, the Conservative campaign faced a miserable winter. Labour led the polls for a few months, and by April 2015, pollsters and pundits were predicting a hung parliament.

The Conservatives made two moves that helped to turn the tables. The first was a new message – to stoke fear that without a clear Conservative majority, Britain would be run by a coalition between Labour and the Scottish National Party.

The second was a new tactic, based on RoadTrip2015. Mark Clarke’s day-long campaign events in the run-up to the general election had given the Conservatives a taste of what the party desperately needed – enthusiastic volunteers knocking on doors in areas that mattered. Historically, Labour had better form bringing activists into marginal battlegrounds, largely thanks to its more active membership drawn from the unions. The Conservative party, with its dwindling and increasingly inactive membership, often found it had no response.

The Conservative party insists that the BattleBus was only intended to conduct national campaigning

But a new plan grew from the seeds of RoadTrip, one that involved busloads of activists and block-booked hotel rooms. BattleBus2015 would send a fleet of coaches to three regions of the UK – the south-west, the Midlands and the north – for the final 10 days of the election campaign. These mobile units, each with around 40 party activists, would stay in hotels in each region, from where they would be loaded onto coaches and driven into different marginals to campaign each day. This would allow the party to flood 29 key seats with much-needed support: nine in the south-west, 10 in the Midlands and 10 in the north.

Receipts for the hotels and coaches, obtained later by Channel 4 News, would prove the operation was expensive. The Electoral Commission later calculated that the BattleBus operation cost £102,483, which works out to around £3,500 for each seat it visited. But while the national party could easily absorb the cost before hitting its spending cap, many of the local candidates were already cutting it fine. If they had to declare the extra costs associated with bringing in more campaigners, the majority would breach the limit.

In the event, £38,996 of the BattleBus costs were declared on the Conservative party’s national return, while the other £63,487, which included the hotels used by volunteers, was not declared at all. The Conservative party put this down to “human error”.

None of the 29 candidates visited by BattleBus declared any of its costs. Whether this should be categorised as national or local spending depends on what the activists did: if they promoted local candidates, even part of the time, then at least some costs associated in bringing them to the constituency should have been declared locally.

The Conservative party insists that BattleBus was only intended to conduct national campaigning. The Electoral Commission report states that it “has found no evidence to suggest that the party had funded the BattleBus2015 campaign with the intention that it would promote or procure the electoral success of candidates”. But, the report continues, “coaches of activists were transported to marginal constituencies to campaign alongside or in close proximity to local campaigners,” and “it is apparent that candidate campaigning did take place during the BattleBus2015 campaign”. It adds that, in the commission’s view, a proportion of the costs should have been declared in candidate campaign filings, “casting doubt” on whether these candidate spending returns were accurate.

The Conservative party has responded to these allegations by insisting that BattleBus volunteers did not promote local candidates. But on Twitter, in the weeks before the election, the BattleBus activists hailed their own efforts to win over voters for specific candidates. On 2 May, one volunteer wrote: “1,300 voters talked to on the doorstep in Amber Valley today for @VoteNigelMills!”. Another posted: “Nice homes in the beautiful Amber Valley – great reaction on the doorsteps in support of Nigel Mills.”

Photographs posted on social media add to the layers of evidence. One young female activist is pictured on a doorstep holding a leaflet bearing the name of Nigel Mills. In the north, a group of activists in Sherwood were photographed holding calling cards for the candidate Mark Spencer, carrying his name and image, and the words: “I called by today with my local team to hear your views.” Channel 4 News has spoken to a handful of volunteers who say their time on the BattleBus involved local campaigning.

Gregg and Louise Kinsell, a married couple from Market Drayton, Shropshire, joined the Conservative party in the run-up to the election, motivated by a mix of patriotic pride, shared values and a liking for David Cameron. They signed up to join BattleBus2015 for its final stretch in the south-west, visiting four constituencies over four days: Stroud; Plymouth, Sutton and Devonport; St Ives and North Cornwall. The aim of the south-west tour was to turn the nine yellow seats of the Liberal Democrats into a sea of blue for the Conservatives – and the Tories won all but one.

The BattleBus operation is still being investigated, but the Kinsells firmly believe that, contrary to claims of Conservative party HQ, they and their fellow volunteers did promote local candidates. “The coach would pull in”, Louise says, “and they’d all be cheering. Honestly, we were like the big hitters coming down to make sure that we win. That’s exactly how it was.”

The couple recall that senior activists gave them scripts about the local candidates to memorise on the bus, in order to be ready to sing their virtues on the doorsteps of undecided voters. Specially prepared briefing notes helped them absorb local issues. And they claim they were handed bundles of locally focused leaflets and calling cards to slip through the letterboxes of prospective voters. The voting intentions of the people they called upon were carefully logged. The couple are clear that they were used as a tactic to “sway marginal seats”, and are angry at the ongoing claim of the Conservative party and some MPs that the BattleBus operation only promoted the national message. “If people are saying – and the MPs concerned in these areas are saying that it was part of a greater expense nationally for the Conservatives, that’s an obvious falsehood,” Gregg says.

Today the investigation into the Conservative victory in South Thanet is staffed by nine officers from the Kent police serious economic crime unit. The questions they are considering are familiar to those raised in the 2014 byelections. Were the hotel costs for visiting Conservative staffers in South Thanet – nearly £20,000 in total – properly declared?

After his election victory, Craig Mackinlay filed expenses of £14,838 for the short campaign – just £178 under the spending limit – but made no mention of the Royal Harbour hotel in Ramsgate where senior party workers had taken rooms. Was that an honest account of his expenses? And if not, who was responsible?

The search for answers has so far taken in boxes of internal Conservative documents, the testimony of campaigners, and a six-hour police interview earlier this month with Mackinlay. But a more basic question about the election remains disputed: who actually ran his South Thanet campaign? The list is longer than it should be.

At the top is the name Nathan Gray, Mackinlay’s election agent. In common with many of the “campaign managers” employed as part of the 40/40 strategy, Gray’s enthusiasm for politics was not matched by his experience. Then 26, he had never done the job before. (Gray denies any wrongdoing.)

In the aftermath of the great victory against Nigel Farage in South Thanet, Gray was largely written out of the story and replaced by Nick Timothy, a long-time special advisor to Theresa May who is now the prime minister’s joint chief of staff. In his book Why the Tories Won, Tim Ross describes how Timothy “was sent to take charge of the party’s flagging campaign to stop Farage in Thanet”. Grant Shapps even said recently that Timothy was “front and centre” in South Thanet. But he was not responsible for filing the expenses return and, when contacted about his involvement, a spokesperson stated that he provided “assistance for the Conservative party’s national team and would have given advice to any candidate who asked for it and indeed did so”. There is no suggestion that Timothy is at fault.

An analysis of the campaign written afterwards for the South Thanet Conservative Association credits someone else entirely: “In February [2015] CCHQ sent a professional team to help us. Their leader, Marion Little, is a very experienced election ‘trouble shooter’, and from the moment she arrived she effectively took control of the whole campaign.”

A Conservative staffer since 1984, Little had held the previous title “battleground director” of the Conservative party. And just as she had a formidable presence in the byelections of Newark, Clacton and Rochester and Strood, so she transformed the South Thanet Conservative’s constituency office into a military command post. Little was also not responsible for filing the election spending for South Thanet but she worked long into the night, battle planning and deploying troops: “Dear Team ‘South Thanet’,” she wrote in an email on 23 March. “Just to confirm that this weeks’ [sic] meeting schedule is as follows …” When Nick Timothy did make suggestions, they were run by Little: “Are we not putting ‘two horse race’ on everything?” he asked her in one email sent on 29 March 2015, before adding: “don’t we need to?”

Little didn’t respond when asked whether her role in South Thanet involved local campaigning.

Buses of activists also descended from London. Volunteers were dubbed the “South Thanet Soldiers”. One Labour campaigner, Peter Wallace, recalled seeing hordes of well-dressed young Conservatives working the constituency week after week. “They were like Terminators,” he said, “straight out of GQ, out of London and on our patch. They blew us away.”

Photographs and videos taken by Conservatives in the final weeks of campaigning show the scale of the resources used to bolster the party. There were visits from Boris Johnson and George Osborne, and groups of campaigners arriving on liveried Conservative coaches ready to work for Craig Mackinlay. On the morning of the election, party co-chairs Grant Shapps and Lord Feldman arrived with Mark Clarke and a coach of last-minute campaigners.

In the end Mackinlay defeated Farage in some style. The problem is that when Timothy and Little stayed down in South Thanet, they lived in some style too. The local spending limit in the election was just £15,016, but the bill for rooms housing the troubleshooters from CCHQ at the Royal Harbour hotel ran to £15,641 alone. Mackinlay denies any wrongdoing.

“They had a few rooms block-booked, yeah,” James Thomas, the owner of the Royal Harbour, told Channel 4 News. “All hotels become headquarters, unofficially sometimes,” he added. “Mr Farage was going to be defeated by them, so they made sure they had the right brains to do that.”

More hotel receipts, uncovered by Channel 4 News, showed more party workersstaying at the Margate Premier Inn, some for 12 nights, with a total cost of £3,809. Little’s name was on the bill, but these costs were not declared in the local return or the party’s national expenses. It appeared to resemble the spending in the 2014 byelections – the money was off-the-books. The difference was that, this time, the Conservatives won.

The first report into the Conservative party’s election expenses was broadcast by Michael Crick on Channel 4 News in late January 2016. It was a short item on a slow news day, which simply asked why the cost of rooms at the Royal Harbour hotel in South Thanet had been declared as part of the Conservatives’ national – rather than local – campaign expenses. Why, Crick asked, would a team of top Conservatives be based at a small provincial hotel miles from anywhere if not to work on behalf of the Conservative candidate fighting Nigel Farage for the seat?

When investigative reporters at Channel Four News began to look at the threads connecting tactics in South Thanet to other high-profile Conservative campaigns, a tangle of receipts and emails revealed the party’s hidden spending elsewhere: undeclared hotels, busloads of activists on specialist missions, and senior CCHQ staff buried deep in provincial England.

For months, the Conservative party repeated that all their campaign spending was “in accordance with the law”. A member of the party’s governing body stepped in front of the cameras on 1 March to announce: “Channel 4 has got it wrong.” But eventually the Electoral Commission, which had been widely criticised as toothless, developed canines and sank them into the case. After pressing the party for three months, they were finally provided with seven boxes of papers in May 2016. The secrets they held would make police investigations inevitable but, even then, the Conservatives dug in.

One of the nation’s leading QCs was dispatched by Craig Mackinlay to Folkestone magistrates’ court to halt a Kent police investigation into election spending offences in South Thanet. He failed, and the detectives’ work continued. By the middle of June, 17 forces were conducting investigations into 27 sitting Conservative MPs. Since then, 12 police forces have passed files to the CPS to review, and up to 20 sitting MPs wait to discover if criminal charges will be brought, while other forces still sift through evidence.