Households, companies and government are all in deficit for the first time since the 1980s writes Chris Giles in The FT

The Scottish economist Adam Smith described Britain as a nation of shopkeepers in his book The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776.

Today, the UK is simply a country of shoppers. Rarely has Britain been consuming so much and saving so little.

As a nation — which statisticians break down into households, companies and the government — Britain spends far more than it earns. On this measure, the UK borrowed 5 per cent of national income in 2015, according to the OECD, the Paris-based international organisation.

This implies that UK households, companies and the government spent 5 per cent more than they earned in that year and financed the deficit by borrowing from overseas.

Britain was still borrowing 5.1 per cent of gross domestic product from foreigners in the third quarter of 2018, according to latest data from the Office for National Statistics on so-called sector balances. Since the 2016 EU referendum, every large sector of the economy — classified as households, companies and the government — has been in deficit at the same time: a situation last recorded in the boom years of the late 1980s.

Senior UK policymakers have long worried that running an economy on such low levels of national savings would be storing up trouble for the future, but they have often been at a loss to find solutions.

Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England, regularly expressed concern over Britain’s adeptness at consuming but felt he had to pump it up further at the BoE by keeping interest rates low for fear of a slump.

He called this a “paradox of policy” and noted an irony in his 2016 book The End of Alchemy that “those countries most in need of this long-term adjustment [to higher national savings levels], the US and the UK, have been the most active in pursuing the short-term stimulus”.

Such is the alarm over the lack of national savings that the ONS issued a stern warning in its most recent release about Britain’s accounts. Rob Kent-Smith, head of GDP at the ONS, said last month that “households spent more than they received for an unprecedented nine quarters in a row”.

Martin Weale of King’s College London, a former external member of the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee, expressed concern that low rates of national savings would lead to future disappointment with living standards.

“National savings is important because if you have a situation where people want to retire you have to ask how they can do it,” Professor Weale said, noting that savings can come from many places — for example, companies’ contributions into defined benefit pension schemes.

“You can save for retirement, you can hope young people will pay for your retirement, you can decide not to retire, or I suppose you could retire and starve,” said Prof Weale. Happy countries, he added, tended to be those with high national savings rates.

Many economists are, however, not nearly as worried. David Miles of Imperial College London and another former MPC member said that low national savings rates might be a flashing warning light, but “the more one delves, if there is a problem, you won’t find it in the aggregate [national savings rate] number” produced by the ONS.

Instead, people should estimate whether households are saving enough for their future needs, companies are investing sufficiently for their long-term prospects and government is maintaining the fabric of the nation, Prof Miles added. In each case there will be some parts of each sector that are fine and others where there are problems, he said.

These issues show up in the measurement of individual sectors by the ONS: government borrowing is now at its lowest level since the early years of the millennium, for example.

In the households sector, the fact that spending is now higher than income relates partly to low savings. But much of the trend is due to sharply rising investment in new homes, which counts towards spending, and paints a much less concerning picture of households’ finances because the sector ends up with valuable assets.

Recommended

UK economic growth

UK economic analysis creates Goldilocks dilemma

But as a nation, one thing has changed for the worse — and this used to be Britain’s get-out-of-jail-free card.

Throughout decades of heavy borrowing by the UK from overseas, policymakers could say British investments abroad were more valuable than equivalents made by foreigners here. So the country’s net investment position — the overseas assets owned by UK residents compared with British equivalents held by foreigners — was positive.

That changed substantially after the financial crisis, and the net investment position is now persistently negative.

Samuel Tombs of Pantheon Macroeconomics said this means “the UK’s dependence on external finance will continue to grow and its stock of external liabilities will increase”.

As any company will verify, in a future downturn a weak balance sheet signals vulnerability and spells trouble.

“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Wednesday 24 April 2019

Tuesday 23 April 2019

Sunday 21 April 2019

My TED talk: how I took on the tech titans in their lair

For more than a year, the Observer writer has been probing a darkness at the heart of Silicon Valley. Last week, at a TED talk that became a global viral sensation, she told the tech billionaires they had broken democracy. What happened next? Carole Cadwalladr in the Guardian

FacebookTwitterPinterest Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey at TED2019 in Vancouver last week. ‘There is no point in quick fixes,’ he said. Photograph: Ryan Lash/TED

That night, though, there was what was described to me as “an emergency dinner” between Anderson and a cadre of senior Facebook executives. They were very angry, my spies told me. But Anderson, one of the most thoughtful people in tech, seemed unruffled.

“There’s always been a strict church and state separation between sponsors and editorial,” he said. “And these are important conversations we need to have. There’s a lot of people here who are very upset about what has happened to the internet. They want to take it back and we have to start figuring out how.” At the end of my talk, he invited Zuckerberg or anyone else at Facebook to come and respond. Spoiler: they never did.

The next day, on stage, Anderson interviewed Jack Dorsey, the co-founder of Twitter. How hard is it to get rid of Nazis from Twitter, Anderson asked him. Dorsey, dressed in a black beanie hat, black hoodie, black jeans and black boots, a monk for the online age, responded, expressionlessly, saying that Nazism was “hard to define”.

There were problems, he admitted, but there was no point in quick fixes. They needed to go “deep”. You’re on a ship, Anderson said, and there’s an iceberg ahead. “And you say… ‘Our boat hasn’t been built to handle it’ and we’re waiting and you are showing this extraordinary calm and we’re all worried but we’re outside saying, ‘Jack, turn the fucking wheel.’ ”

Spoiler: the fucking wheel remains unturned.

Anderson gave credit to Dorsey for actually showing up. And it’s true he did. He showed guts for doing what Zuckerberg and Sandberg would not.But, for many, including me, he might as well not have bothered. What came across most strongly, chillingly, was the complete absence of emotion – any emotion – in Dorsey’s face, expression, demeanour or voice.

When Cyndi Stivers, a TED director, asked me last summer if I’d be interested in doing a talk, I knew I would be terrified, but I knew I had to do it. The one constant in the time I have been reporting this story has been the lack of mainstream broadcast coverage, the absence of other newspapers picking it up, the failure by even senior, well-respected journalists to understand the issues at stake, the wilful misinterpretation of the facts by the right-wing press, the almost total silence from both the government and the opposition.

The brilliance of the TED format, its slick production, deft editing and clever curation, is that it offers an opportunity to bypass the traditional media – the BBC most especially – that has failed or refused to cover this story. TED Talks speak to an audience who desperately need to know what happened but almost certainly don’t: the disenfranchised teenagers and young people who had no vote but who will be affected by this perfect storm of technology and criminality for the rest of their lives.

But TED is a tough, pressured, hugely stressful gig, even for experienced public speakers, and I’m not that. Standing in the wings waiting to go on, I told the stage manager that my heart was racing uncontrollably and in an act of great kindness, she grasped both my hands and made me take breath after breath. And what you don’t see in the video – deftly edited out – is the awful, heart-stopping moment when I forgot a line, followed by another act of collective kindness, a spontaneous empathic cheer as I composed myself and found my cue. “That’s when the audience came onside,” an attendee told me. “You were human. That’s when you won them over.”

On the TED stage, dressed in a hat and a hood, Dorsey appeared – and I can’t think of any other way of saying this – insentient. And when I make the same observation to an older tech titan, he tells me how he once went with Zuckerberg on a 15-hour flight on a private jet with 16 other people and Zuckerberg never said a word to anyone for the entire duration.

It’s all I can think about by the end of the week. For five days, I’ve been overwhelmed by support and understanding and encouragement from wellwishers, person after person who tells me they were moved or terrified by my talk, by the danger posed by this technology that has unleashed a potential for destruction that we neither saw coming nor know how to contain.

Dorsey can see the iceberg but doesn’t seem to feel our terror. Or understand it. In an interview last summer, US journalist Kara Swisher, repeatedly asked Zuckerberg how he felt about Facebook’s role in inciting genocide in Myanmar – as established by the UN – and he couldn’t or wouldn’t answer.

The world needs all kinds of brains. But in the situation we are in, with the dangers we face, it’s not these kinds of brains. These are brilliant men. They have created platforms of unimaginable complexity. But if they’re not sick to their stomach about what has happened in Myanmar or overwhelmed by guilt about how their platforms were used by Russian intelligence to subvert their own country’s democracy, or sickened by their own role in what happened in New Zealand, they’re not fit to hold these jobs or wield this unimaginable power.

I walked among the tech gods last week. I don’t think they set out to enable massacres to be live-streamed. Or massive electoral fraud in a once-in-a-lifetime, knife-edge vote. But they did. If they don’t feel guilt, shame and remorse, if they don’t have a burning desire to make amends, their boards, shareholders, investors, employees and family members need to get them out.

We can see the iceberg. We know it’s coming. That’s the lesson of TED 2019. We all know it. There are only five people in the room who apparently don’t: Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Jack Dorsey.

Carole Cadwalladr speaking at TED2019 last week. The Observer journalist was invited to give a talk in a session tagged Truth. Photograph: Marla Aufmuth/TED

If Silicon Valley is the beast, then TED is its belly. And on Monday, I entered it. The technology conference that has become a global media phenomenon with its short, punchy TED Talks that promote “Ideas Worth Spreading” is the closest thing that Silicon Valley has to a safe space.

A safe space that was breached last week. A breach that I was not just there to witness, but that I actively participated in. I can’t claim either credit or responsibility – I didn’t invite myself to the conference, held annually in Vancouver, or programme my talk in a session called “Truth”. But I did take the reporting that we have been publishing in the Observer over the past two and a half years, I did condense it into a 15-minute talk, and I did deliver it on the TED main stage directly to the people I described as “the Gods of Silicon Valley: Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Jack Dorsey”. The founders of Facebook and Google – who were sponsoring the conference – and the co-founder of Twitter – who was speaking at it.

I did tell them that they had facilitated multiple crimes in the EU referendum. That as things stood, I didn’t think it was possible to have free and fair elections ever again. That liberal democracy was broken. And they had broke it.

It was only later that I began to realise quite what TED had done: how, in this setting, with this crowd, it had committed the equivalent of inviting the fox into the henhouse. And I was the fox. Or as one attendee put it: “You came into their temple,” he said. “And shat on their altar.”

I did. Not least, I discovered, because I named them. Because nobody had told me not to. And so I called them out, in a room that included their peers, mentors, employees, friends and investors.

A room that fell silent when I ended and then erupted in whoops and cheers. “It’s what we’re all thinking,” one person told me. “But it’s been the thing that nobody had actually said.”

Because it isn’t an exaggeration to say that TED is the holy temple of tech. In the early days, it was where the new miracles of technology were first unveiled – the Apple Macintosh and the CD-Rom – and in recent years it’s become the place that has most clearly articulated the Silicon Valley gospel. For many, including myself, TED was how they discovered the excitement and possibilities of technology. A brand of tech utopianism that, even as the world has darkened, TED has found hard to give up.

But now it has. Or at least it’s sent up a flare. A bold, impossible-to-miss stroke by its high priest, Chris Anderson, a thoughtful Brit who bought TED when it was in its first incarnation – a secretive Californian conference for the masters of the universe – and made it a multi-million-dollar media organisation.

Anderson hadn’t just invited me in, he put me front and centre, in the first session, unavoidable, even – maybe especially – for his sponsors.

In the simulcast lounge where conference attendees – who pay between $10,000 and $250,000 a ticket – lounge on soft seating and watch on screens, was Sergey Brin, Google’s co-founder. “I saw his eyes flicker when you said his name,” one person told me. “As if he was checking if anybody was looking.”

In the theatre, senior executives of Facebook had been “warned” beforehand. And within minutes of stepping off stage, I was told that its press team had already lodged an official complaint. In fairness, what multi-billion dollar corporation with armies of PRs, lawyers and crisis teams, not to mention, embarrassingly, our former deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, wouldn’t want to push back on the charge that it has broken democracy?

Facebook’s difficulty is that it had no grounds to challenge my statement. No counter-evidence. If it was innocent of all charges, why hasn’t Mark Zuckerberg come to Britain and answered parliament’s questions? Though a member of the TED team told me, before the session had even ended, that Facebook had raised a serious challenge to the talk to claim “factual inaccuracies” and she warned me that they had been obliged to send them my script. What factual inaccuracies, we both wondered. “Let’s see what they come back with in the morning,” she said. Spoiler: they never did.

If Silicon Valley is the beast, then TED is its belly. And on Monday, I entered it. The technology conference that has become a global media phenomenon with its short, punchy TED Talks that promote “Ideas Worth Spreading” is the closest thing that Silicon Valley has to a safe space.

A safe space that was breached last week. A breach that I was not just there to witness, but that I actively participated in. I can’t claim either credit or responsibility – I didn’t invite myself to the conference, held annually in Vancouver, or programme my talk in a session called “Truth”. But I did take the reporting that we have been publishing in the Observer over the past two and a half years, I did condense it into a 15-minute talk, and I did deliver it on the TED main stage directly to the people I described as “the Gods of Silicon Valley: Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Jack Dorsey”. The founders of Facebook and Google – who were sponsoring the conference – and the co-founder of Twitter – who was speaking at it.

I did tell them that they had facilitated multiple crimes in the EU referendum. That as things stood, I didn’t think it was possible to have free and fair elections ever again. That liberal democracy was broken. And they had broke it.

It was only later that I began to realise quite what TED had done: how, in this setting, with this crowd, it had committed the equivalent of inviting the fox into the henhouse. And I was the fox. Or as one attendee put it: “You came into their temple,” he said. “And shat on their altar.”

I did. Not least, I discovered, because I named them. Because nobody had told me not to. And so I called them out, in a room that included their peers, mentors, employees, friends and investors.

A room that fell silent when I ended and then erupted in whoops and cheers. “It’s what we’re all thinking,” one person told me. “But it’s been the thing that nobody had actually said.”

Because it isn’t an exaggeration to say that TED is the holy temple of tech. In the early days, it was where the new miracles of technology were first unveiled – the Apple Macintosh and the CD-Rom – and in recent years it’s become the place that has most clearly articulated the Silicon Valley gospel. For many, including myself, TED was how they discovered the excitement and possibilities of technology. A brand of tech utopianism that, even as the world has darkened, TED has found hard to give up.

But now it has. Or at least it’s sent up a flare. A bold, impossible-to-miss stroke by its high priest, Chris Anderson, a thoughtful Brit who bought TED when it was in its first incarnation – a secretive Californian conference for the masters of the universe – and made it a multi-million-dollar media organisation.

Anderson hadn’t just invited me in, he put me front and centre, in the first session, unavoidable, even – maybe especially – for his sponsors.

In the simulcast lounge where conference attendees – who pay between $10,000 and $250,000 a ticket – lounge on soft seating and watch on screens, was Sergey Brin, Google’s co-founder. “I saw his eyes flicker when you said his name,” one person told me. “As if he was checking if anybody was looking.”

In the theatre, senior executives of Facebook had been “warned” beforehand. And within minutes of stepping off stage, I was told that its press team had already lodged an official complaint. In fairness, what multi-billion dollar corporation with armies of PRs, lawyers and crisis teams, not to mention, embarrassingly, our former deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, wouldn’t want to push back on the charge that it has broken democracy?

Facebook’s difficulty is that it had no grounds to challenge my statement. No counter-evidence. If it was innocent of all charges, why hasn’t Mark Zuckerberg come to Britain and answered parliament’s questions? Though a member of the TED team told me, before the session had even ended, that Facebook had raised a serious challenge to the talk to claim “factual inaccuracies” and she warned me that they had been obliged to send them my script. What factual inaccuracies, we both wondered. “Let’s see what they come back with in the morning,” she said. Spoiler: they never did.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey at TED2019 in Vancouver last week. ‘There is no point in quick fixes,’ he said. Photograph: Ryan Lash/TED

That night, though, there was what was described to me as “an emergency dinner” between Anderson and a cadre of senior Facebook executives. They were very angry, my spies told me. But Anderson, one of the most thoughtful people in tech, seemed unruffled.

“There’s always been a strict church and state separation between sponsors and editorial,” he said. “And these are important conversations we need to have. There’s a lot of people here who are very upset about what has happened to the internet. They want to take it back and we have to start figuring out how.” At the end of my talk, he invited Zuckerberg or anyone else at Facebook to come and respond. Spoiler: they never did.

The next day, on stage, Anderson interviewed Jack Dorsey, the co-founder of Twitter. How hard is it to get rid of Nazis from Twitter, Anderson asked him. Dorsey, dressed in a black beanie hat, black hoodie, black jeans and black boots, a monk for the online age, responded, expressionlessly, saying that Nazism was “hard to define”.

There were problems, he admitted, but there was no point in quick fixes. They needed to go “deep”. You’re on a ship, Anderson said, and there’s an iceberg ahead. “And you say… ‘Our boat hasn’t been built to handle it’ and we’re waiting and you are showing this extraordinary calm and we’re all worried but we’re outside saying, ‘Jack, turn the fucking wheel.’ ”

Spoiler: the fucking wheel remains unturned.

Anderson gave credit to Dorsey for actually showing up. And it’s true he did. He showed guts for doing what Zuckerberg and Sandberg would not.But, for many, including me, he might as well not have bothered. What came across most strongly, chillingly, was the complete absence of emotion – any emotion – in Dorsey’s face, expression, demeanour or voice.

When Cyndi Stivers, a TED director, asked me last summer if I’d be interested in doing a talk, I knew I would be terrified, but I knew I had to do it. The one constant in the time I have been reporting this story has been the lack of mainstream broadcast coverage, the absence of other newspapers picking it up, the failure by even senior, well-respected journalists to understand the issues at stake, the wilful misinterpretation of the facts by the right-wing press, the almost total silence from both the government and the opposition.

The brilliance of the TED format, its slick production, deft editing and clever curation, is that it offers an opportunity to bypass the traditional media – the BBC most especially – that has failed or refused to cover this story. TED Talks speak to an audience who desperately need to know what happened but almost certainly don’t: the disenfranchised teenagers and young people who had no vote but who will be affected by this perfect storm of technology and criminality for the rest of their lives.

But TED is a tough, pressured, hugely stressful gig, even for experienced public speakers, and I’m not that. Standing in the wings waiting to go on, I told the stage manager that my heart was racing uncontrollably and in an act of great kindness, she grasped both my hands and made me take breath after breath. And what you don’t see in the video – deftly edited out – is the awful, heart-stopping moment when I forgot a line, followed by another act of collective kindness, a spontaneous empathic cheer as I composed myself and found my cue. “That’s when the audience came onside,” an attendee told me. “You were human. That’s when you won them over.”

On the TED stage, dressed in a hat and a hood, Dorsey appeared – and I can’t think of any other way of saying this – insentient. And when I make the same observation to an older tech titan, he tells me how he once went with Zuckerberg on a 15-hour flight on a private jet with 16 other people and Zuckerberg never said a word to anyone for the entire duration.

It’s all I can think about by the end of the week. For five days, I’ve been overwhelmed by support and understanding and encouragement from wellwishers, person after person who tells me they were moved or terrified by my talk, by the danger posed by this technology that has unleashed a potential for destruction that we neither saw coming nor know how to contain.

Dorsey can see the iceberg but doesn’t seem to feel our terror. Or understand it. In an interview last summer, US journalist Kara Swisher, repeatedly asked Zuckerberg how he felt about Facebook’s role in inciting genocide in Myanmar – as established by the UN – and he couldn’t or wouldn’t answer.

The world needs all kinds of brains. But in the situation we are in, with the dangers we face, it’s not these kinds of brains. These are brilliant men. They have created platforms of unimaginable complexity. But if they’re not sick to their stomach about what has happened in Myanmar or overwhelmed by guilt about how their platforms were used by Russian intelligence to subvert their own country’s democracy, or sickened by their own role in what happened in New Zealand, they’re not fit to hold these jobs or wield this unimaginable power.

I walked among the tech gods last week. I don’t think they set out to enable massacres to be live-streamed. Or massive electoral fraud in a once-in-a-lifetime, knife-edge vote. But they did. If they don’t feel guilt, shame and remorse, if they don’t have a burning desire to make amends, their boards, shareholders, investors, employees and family members need to get them out.

We can see the iceberg. We know it’s coming. That’s the lesson of TED 2019. We all know it. There are only five people in the room who apparently don’t: Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Jack Dorsey.

Friday 19 April 2019

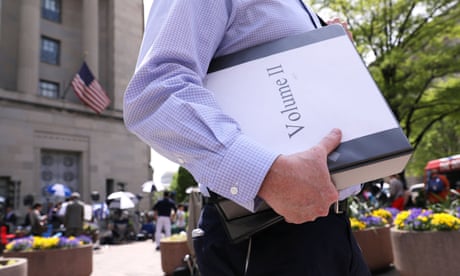

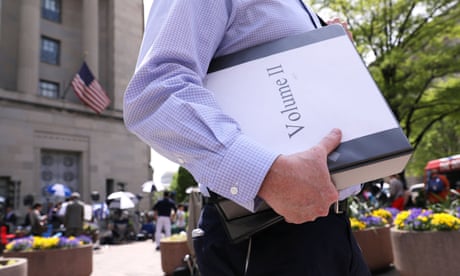

The Mueller report shows that bad guys who play dirty, like Trump, always win

The attorney general has protected his boss, and impeachment looks futile. But the Democrats still have a duty to act writes Jonathan Freedland in The Guardian

Mueller report unable to clear Trump of obstruction of justice

The 448-page Mueller report, even in its redacted form – pockmarked with blacked-out names and passages – serves up enough ammunition to destroy this president, whether through impeachment proceedings this year or by denying him re-election in 2020. Its pages confirm one scandal after another, supplying the detailed hard facts to vindicate the very claims that Trump breezily dismissed at the time as fake news. That Mueller did not take the final step – accusing the US president of both collusion with the Russians and obstruction of justice – tells its own story, which we’ll come to. But it was hardly for lack of evidence.

On the contrary, the evidence is copious. No wonder Trump’s handpicked attorney general, William Barr held onto the report so long, issuing only his own, highly selective four-page summary last month, a document that included not so much as a single full sentence from Mueller’s text, holding up instead a half-line here or a fragment there that might show the president in a favourable light.

Now we know why. For the Mueller report is packed with damning proof that Trump and his team cheered on the “sweeping and systematic” Russian attempt to sway the 2016 presidential election, that they expected to “benefit electorally from information stolen and released through Russian efforts,” that they actively planned campaign strategy around each new release of emails hacked from Democrat HQ by Russian intelligence, emails helpfully funnelled through WikiLeaks. (Mueller has the documents that shows Assange telling his acolytes as early as November 2015 that “we believe it would be much better for GOP [the Republicans] to win.”)

Mueller emerges as a ref who allowed himself to be bullied by an especially belligerent star player

What’s more, Trump folk, including the candidate’s eldest son, met a Kremlin emissary promising dirt on Hillary Clinton; a Trump aide tried to establish a back channel to Vladimir Putin’s government; and all the while, the Trump campaign denied there was any Russian effort to meddle in US democracy. Still, none of this rose to the level of a crime for Mueller because “collusion is not a specific offense … nor is it a term of art in federal criminal law”. Mueller chose instead to set the bar so high it was bound to be out of reach: he needed to see proof of an actual “agreement” between Trump and the Kremlin to break the law to fix the 2016 election. Absent that, and Trump was off the hook of criminal misconduct.

The pattern in the second area, obstruction of justice, is even more egregious. The report lays out the 10 different ways Trump sought to intimidate, deceive or thwart those investigating him, including Mueller himself. He told his White House counsel to get Mueller sacked, then when the counsel refused, Trump ordered him to deny Trump had given that order. Ranting and swearing, the Trump of Mueller’s account is a low-rent Queens hoodlum, Joe Pesci in the Oval Office, lying day and night and ordering everyone around him – including the heads of the intelligence agencies – to lie too.

Why, then, does Mueller not come out with it and charge Trump with obstruction? Part of the answer is that Mueller was swayed by the doctrine that says a sitting president cannot be indicted. Given that, “we determined not to apply an approach that could potentially result in a judgment that the president committed crimes”. This is breathtaking logic, which amounts to: “Because we knew we couldn’t indict Trump for crimes, we made sure not to find any.”

Time after time, Mueller made judgment calls that helped the president. Sure, Trump wanted to obstruct justice – but he was blocked by aides who didn’t “accede to his requests”, so, for Mueller it didn’t count (as if obstruction has to be successful to be a crime). To allege obstruction, one has to know the intention of the alleged obstructor and that requires an interview with the accused: but when Trump refused to speak to Mueller in person, the special counsel decided not to use his legal right to subpoena the president, because that would have caused a “substantial delay” and the pressure was on to wind up the investigation. But who exactly was demanding Mueller wrap up? Why, it was Trump and his cheerleaders of course. Mueller emerges as a ref who allowed himself to be bullied by an especially belligerent star player.

But this is about more than a mere difference of personalities, with gangster Trump running rings around his boy-scout pursuers. It’s about a difference in political culture. For the Trump presidency, exposed in all its ugliness in the Mueller report, is predicated on a willingness to shred the rules and norms that sustain liberal democracy – and it relies for its success on the unwillingness of liberal democracy’s guardians to do the same.

A cardboard cutout of US attorney general William Barr is seen as protesters hold signs outside the White House. Photograph: Carlos Barría/Reuters

So Trump has no compunction in violating every tacit convention that kept (most of) his predecessors in check. To take one example, presidents are meant to remain at arm’s length from the department of justice, allowing the attorney general to act with independence. Richard Nixon crossed that line, and eventually paid for it with his job. But it’s clear that Trump regards the attorney general as his personal lawyer, and Barr has been happy to play that role – spinning for Trump on Thursday as if he were a hack spokesman rather than the nation’s senior law officer. Earlier Barr had briefed the White House on the Mueller report’s contents, when all precedent commanded that he keep it confidential. Meanwhile, even as Barr bowdlerised his report, Mueller observed the very proprieties that Trump and Barr had trashed, and stayed dutifully silent.

There is a fundamental mismatch here: Trump cutting every corner, trampling on every ethical guideline, while Mueller and those like him primly weigh up the legal niceties and nuances. They are thumbing through the rulebook of the monastery, while in front of them a mafia don creates havoc. This is the authoritarian populists’ great strength, and not only in the US: they break all the rules, banking on the fact that their opponents will stick to them and be weaker as a result. It is the perennial villain’s advantage: they play dirty knowing you’ll play nice. They’re doing it again now, claiming exoneration when Mueller pointedly does not exonerate Trump of obstruction and when he has revealed so much that is, as the lawyers have it, “lawful but awful”.

And yet, Mueller has not failed. He has handed Congress that revolver along with a full clip of ammunition, thereby giving the Democratic-controlled House a dilemma. Should it impeach Donald Trump on the basis of the evidence Mueller has set out? After all, the constitution demands action against a president guilty of “high crimes and misdemeanors”, a category not confined to prosecutable felonies. Mueller’s report includes a heavy hint that it is Congress’s task to apply “our constitutional system of checks and balances and the principle that no person is above the law”.

The trouble is, while Democrats might have the votes to impeach Trump – that is, charge him – in the House, they do not have the two-thirds majority, 67 senators, they would need to convict him in the Senate, thereby removing him from office. Republicans are more tribal than they were in Nixon’s day: they have repeatedly shown that they will simply rally behind their leader, no matter what he’s done. Trump would stay in office, just as Bill Clinton did in 1999. That near-certain prospect of failure, coupled with the fact that impeachment would devour Democrats’ energies and consume their agenda when they’d rather be talking about jobs or healthcare, makes it politically unappealing.

Even so, they cannot ignore what Mueller has shown them. If they did, they would be accepting what Trump has done: they would be normalising his destruction of essential norms, allowing him to tear down those barriers that stand between liberal democracy and a form of elective authoritarianism, a gangster state. Impeachment will not be politically fruitful. It may even be doomed. But it might just be Democrats’ duty.

‘The Trump campaign denied there was any Russian effort to meddle in US democracy. Still, none of this rose to the level of a crime.’ Photograph: Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

Those who had long hoped Robert Mueller – the mostly silent sheriff riding into town to ensure good triumphed over evil – would be the saviour to deliver America and the world from Donald Trump are naturally disappointed. Mueller’s report, released yesterday , did not quite deliver the smoking gun Trump’s enemies had dreamed of. Instead, it handed the American public and their elected representatives a fully loaded revolver, with a note attached: “Now it’s up to you”.

Those who had long hoped Robert Mueller – the mostly silent sheriff riding into town to ensure good triumphed over evil – would be the saviour to deliver America and the world from Donald Trump are naturally disappointed. Mueller’s report, released yesterday , did not quite deliver the smoking gun Trump’s enemies had dreamed of. Instead, it handed the American public and their elected representatives a fully loaded revolver, with a note attached: “Now it’s up to you”.

Mueller report unable to clear Trump of obstruction of justice

The 448-page Mueller report, even in its redacted form – pockmarked with blacked-out names and passages – serves up enough ammunition to destroy this president, whether through impeachment proceedings this year or by denying him re-election in 2020. Its pages confirm one scandal after another, supplying the detailed hard facts to vindicate the very claims that Trump breezily dismissed at the time as fake news. That Mueller did not take the final step – accusing the US president of both collusion with the Russians and obstruction of justice – tells its own story, which we’ll come to. But it was hardly for lack of evidence.

On the contrary, the evidence is copious. No wonder Trump’s handpicked attorney general, William Barr held onto the report so long, issuing only his own, highly selective four-page summary last month, a document that included not so much as a single full sentence from Mueller’s text, holding up instead a half-line here or a fragment there that might show the president in a favourable light.

Now we know why. For the Mueller report is packed with damning proof that Trump and his team cheered on the “sweeping and systematic” Russian attempt to sway the 2016 presidential election, that they expected to “benefit electorally from information stolen and released through Russian efforts,” that they actively planned campaign strategy around each new release of emails hacked from Democrat HQ by Russian intelligence, emails helpfully funnelled through WikiLeaks. (Mueller has the documents that shows Assange telling his acolytes as early as November 2015 that “we believe it would be much better for GOP [the Republicans] to win.”)

Mueller emerges as a ref who allowed himself to be bullied by an especially belligerent star player

What’s more, Trump folk, including the candidate’s eldest son, met a Kremlin emissary promising dirt on Hillary Clinton; a Trump aide tried to establish a back channel to Vladimir Putin’s government; and all the while, the Trump campaign denied there was any Russian effort to meddle in US democracy. Still, none of this rose to the level of a crime for Mueller because “collusion is not a specific offense … nor is it a term of art in federal criminal law”. Mueller chose instead to set the bar so high it was bound to be out of reach: he needed to see proof of an actual “agreement” between Trump and the Kremlin to break the law to fix the 2016 election. Absent that, and Trump was off the hook of criminal misconduct.

The pattern in the second area, obstruction of justice, is even more egregious. The report lays out the 10 different ways Trump sought to intimidate, deceive or thwart those investigating him, including Mueller himself. He told his White House counsel to get Mueller sacked, then when the counsel refused, Trump ordered him to deny Trump had given that order. Ranting and swearing, the Trump of Mueller’s account is a low-rent Queens hoodlum, Joe Pesci in the Oval Office, lying day and night and ordering everyone around him – including the heads of the intelligence agencies – to lie too.

Why, then, does Mueller not come out with it and charge Trump with obstruction? Part of the answer is that Mueller was swayed by the doctrine that says a sitting president cannot be indicted. Given that, “we determined not to apply an approach that could potentially result in a judgment that the president committed crimes”. This is breathtaking logic, which amounts to: “Because we knew we couldn’t indict Trump for crimes, we made sure not to find any.”

Time after time, Mueller made judgment calls that helped the president. Sure, Trump wanted to obstruct justice – but he was blocked by aides who didn’t “accede to his requests”, so, for Mueller it didn’t count (as if obstruction has to be successful to be a crime). To allege obstruction, one has to know the intention of the alleged obstructor and that requires an interview with the accused: but when Trump refused to speak to Mueller in person, the special counsel decided not to use his legal right to subpoena the president, because that would have caused a “substantial delay” and the pressure was on to wind up the investigation. But who exactly was demanding Mueller wrap up? Why, it was Trump and his cheerleaders of course. Mueller emerges as a ref who allowed himself to be bullied by an especially belligerent star player.

But this is about more than a mere difference of personalities, with gangster Trump running rings around his boy-scout pursuers. It’s about a difference in political culture. For the Trump presidency, exposed in all its ugliness in the Mueller report, is predicated on a willingness to shred the rules and norms that sustain liberal democracy – and it relies for its success on the unwillingness of liberal democracy’s guardians to do the same.

A cardboard cutout of US attorney general William Barr is seen as protesters hold signs outside the White House. Photograph: Carlos Barría/Reuters

So Trump has no compunction in violating every tacit convention that kept (most of) his predecessors in check. To take one example, presidents are meant to remain at arm’s length from the department of justice, allowing the attorney general to act with independence. Richard Nixon crossed that line, and eventually paid for it with his job. But it’s clear that Trump regards the attorney general as his personal lawyer, and Barr has been happy to play that role – spinning for Trump on Thursday as if he were a hack spokesman rather than the nation’s senior law officer. Earlier Barr had briefed the White House on the Mueller report’s contents, when all precedent commanded that he keep it confidential. Meanwhile, even as Barr bowdlerised his report, Mueller observed the very proprieties that Trump and Barr had trashed, and stayed dutifully silent.

There is a fundamental mismatch here: Trump cutting every corner, trampling on every ethical guideline, while Mueller and those like him primly weigh up the legal niceties and nuances. They are thumbing through the rulebook of the monastery, while in front of them a mafia don creates havoc. This is the authoritarian populists’ great strength, and not only in the US: they break all the rules, banking on the fact that their opponents will stick to them and be weaker as a result. It is the perennial villain’s advantage: they play dirty knowing you’ll play nice. They’re doing it again now, claiming exoneration when Mueller pointedly does not exonerate Trump of obstruction and when he has revealed so much that is, as the lawyers have it, “lawful but awful”.

And yet, Mueller has not failed. He has handed Congress that revolver along with a full clip of ammunition, thereby giving the Democratic-controlled House a dilemma. Should it impeach Donald Trump on the basis of the evidence Mueller has set out? After all, the constitution demands action against a president guilty of “high crimes and misdemeanors”, a category not confined to prosecutable felonies. Mueller’s report includes a heavy hint that it is Congress’s task to apply “our constitutional system of checks and balances and the principle that no person is above the law”.

The trouble is, while Democrats might have the votes to impeach Trump – that is, charge him – in the House, they do not have the two-thirds majority, 67 senators, they would need to convict him in the Senate, thereby removing him from office. Republicans are more tribal than they were in Nixon’s day: they have repeatedly shown that they will simply rally behind their leader, no matter what he’s done. Trump would stay in office, just as Bill Clinton did in 1999. That near-certain prospect of failure, coupled with the fact that impeachment would devour Democrats’ energies and consume their agenda when they’d rather be talking about jobs or healthcare, makes it politically unappealing.

Even so, they cannot ignore what Mueller has shown them. If they did, they would be accepting what Trump has done: they would be normalising his destruction of essential norms, allowing him to tear down those barriers that stand between liberal democracy and a form of elective authoritarianism, a gangster state. Impeachment will not be politically fruitful. It may even be doomed. But it might just be Democrats’ duty.

Who owns the country? The secretive companies hoarding England's land

Multi-million pound corporations with complex structures have purchased the very ground we walk on – and we are only just beginning to discover the damage it is doing to Britain. By Guy Shrubsole in The Guardian

Despite owning 15,000 hectares (37,000 acres) of land, managing a property portfolio worth £2.3bn and having control over huge swaths of central Manchester and Liverpool, very few people have heard of a company named Peel Holdings. It owns the Manchester Ship Canal. It built the Trafford Centre shopping complex and, more recently, sold it in the largest single property acquisition in Britain’s history. It was the developer behind the MediaCityUK site in Salford, to which the BBC and ITV have relocated many of their operations in recent years. Airports, fracking, retail – the list of Peel business interests stretches on and on.

Peel Holdings operates behind the scenes, quietly acquiring land and real estate, cutting billion-pound deals and influencing numerous planning decisions. Its investment decisions have had an enormous impact, whether for good or ill, on the places where millions of people live and work.

Peel’s ultimate owner, the billionaire John Whittaker, is notoriously publicity-shy: he lives on the Isle of Man, has never given an interview and helicopters into his company’s offices for board meetings. He built Peel Holdings in the 1970s and 80s by buying up a series of companies whose fortunes had decayed, but which still controlled valuable land. Foremost among these was the Manchester Ship Canal Company, purchased in 1987. The canal turned out to be valuable not simply as a freight route, but also because of the redevelopment potential of the land that flanked it.

Half of England is owned by less than 1% of the population

Peel Holdings tends not to show its hand in public. Like many companies, it prefers its forays into public political debate to be conducted via intermediary bodies and corporate coalitions. In 2008, it emerged that Peel was a dominant force behind a business grouping that had formed to lobby against Manchester’s proposed congestion charge. The charge was aimed at cutting traffic and reducing the toxic car fumes choking the city. But Peel, as owners of the out-of-town Trafford Centre shopping mall, feared that a congestion charge would be bad for business, discouraging shoppers from driving through central Manchester to reach the mall. Peel’s lobbying paid off: voters rejected the charge in the local referendum and the proposal was dropped.

Throughout England, cash-strapped councils are being outgunned by corporate developers pressing to get their way. The situation is exacerbated by a system that has allowed companies like Peel to keep their corporate structures obscure and their landholdings hidden. A 2013 report by Liverpool-based thinktank Ex Urbe found “well in excess of 300 separately registered UK companies owned or controlled” by Peel. Tracing the conglomerate’s structure is an investigator’s nightmare. Try it yourself on the Companies House website: type in “Peel Land and Property Investments PLC”, and then click through to persons with significant control. This gives you the name of its parent company, Peel Investments Holdings Ltd. So far, so good. But then repeat the steps for the parent company, and yet another holding company emerges; then another, and another. It’s like a series of Russian dolls, one nested inside another.

Until recently, it was even harder to get a handle on the land Peel Holdings owns. Sometimes the company has provided a tantalising glimpse: one map it produced in 2015, as part of some marketing spiel around the “northern powerhouse”, showcases 150 sites it owns across the north-west. It confirms the vast spread of Peel’s landed interests – from Liverpool John Lennon airport, through shale gas well pads, to one of the UK’s largest onshore wind farms. But it’s clearly not everything. A more exhaustive, independent list of the company’s landholdings might allow communities to be forewarned of future developments. As Ex Urbe’s report on Peel concludes: “Peel schemes rarely come to light until they are effectively a fait accompli and the conglomerate is confident they will go ahead, irrespective of public opinion.”

While Peel Holdings is unusual for the sheer amount of land it controls, it is also illustrative of corporate landowners everywhere. Corporations looking to develop land have numerous tricks up their sleeve that they can use to evade scrutiny and get their way, from shell company structures to offshore entities. Companies with big enough budgets can often ride roughshod over the planning system, beating cash-strapped councils and volunteer community groups. And companies have for a long time benefited from having their landholdings kept secret, giving them the element of surprise when it comes to lobbying councils over planning decisions and the use of public space. But now, at long last, that is starting to change. If we want to “take back control” of our country, we need to understand how much of it is currently controlled by corporations.

In 2015, the Private Eye journalist Christian Eriksson lodged a freedom of information (FOI) request with the Land Registry, the official record of land ownership in England and Wales. He asked it to release a database detailing the area of land owned by all UK-registered companies and corporate bodies. Eriksson later shared this database with me, and what it revealed was astonishing. Here, laid bare after the dataset had been cleaned up, was a picture of corporate control: companies today own about 2.6m hectares of land, or roughly 18% of England and Wales.

In the unpromising format of an Excel spreadsheet, a compelling picture emerged. Alongside the utilities privatised by Margaret Thatcher and John Major – the water companies, in particular – and the big corporate landowners, were PLCs with multiple shareholders. There were household names, such as Tesco, Tata Steel and the housebuilder Taylor Wimpey, and others more obscure. MRH Minerals, for example, appeared to own 28,000 hectares of land, making it one of the biggest corporate landowners in England and Wales.

Gradually, I pieced together a list of what looked to be the top 50 landowning companies, which together own more than 405,000 hectares of England and Wales. Peel Holdings and many of its subsidiaries, unsurprisingly, feature high on the list. But while the dataset revealed in stark detail the area of land owned by UK-based companies, it did nothing to tell us what they owned, and where.

That would take another two years to emerge. Meanwhile, Eriksson had been busy at work with his Private Eye colleague Richard Brooks and the computer programmer Anna Powell-Smith, delving into another form of corporate landowner – firms based overseas, yet owning land in the UK. Of particular interest were companies based in offshore tax havens, a wholly legal but controversial practice, given the opportunities offshore ownership gives for possible tax avoidance and for concealing the identities of who ultimately controls a company. Further FOI requests to the Land Registry by Eriksson hit the jackpot when he was sent – “accidentally”, the Land Registry would later claim – a huge dataset of overseas and offshore-registered companies that had bought land in England and Wales between 2005 and 2014: some 113,119 hectares of land and property, worth a staggering £170bn.

Despite owning 15,000 hectares (37,000 acres) of land, managing a property portfolio worth £2.3bn and having control over huge swaths of central Manchester and Liverpool, very few people have heard of a company named Peel Holdings. It owns the Manchester Ship Canal. It built the Trafford Centre shopping complex and, more recently, sold it in the largest single property acquisition in Britain’s history. It was the developer behind the MediaCityUK site in Salford, to which the BBC and ITV have relocated many of their operations in recent years. Airports, fracking, retail – the list of Peel business interests stretches on and on.

Peel Holdings operates behind the scenes, quietly acquiring land and real estate, cutting billion-pound deals and influencing numerous planning decisions. Its investment decisions have had an enormous impact, whether for good or ill, on the places where millions of people live and work.

Peel’s ultimate owner, the billionaire John Whittaker, is notoriously publicity-shy: he lives on the Isle of Man, has never given an interview and helicopters into his company’s offices for board meetings. He built Peel Holdings in the 1970s and 80s by buying up a series of companies whose fortunes had decayed, but which still controlled valuable land. Foremost among these was the Manchester Ship Canal Company, purchased in 1987. The canal turned out to be valuable not simply as a freight route, but also because of the redevelopment potential of the land that flanked it.

Half of England is owned by less than 1% of the population

Peel Holdings tends not to show its hand in public. Like many companies, it prefers its forays into public political debate to be conducted via intermediary bodies and corporate coalitions. In 2008, it emerged that Peel was a dominant force behind a business grouping that had formed to lobby against Manchester’s proposed congestion charge. The charge was aimed at cutting traffic and reducing the toxic car fumes choking the city. But Peel, as owners of the out-of-town Trafford Centre shopping mall, feared that a congestion charge would be bad for business, discouraging shoppers from driving through central Manchester to reach the mall. Peel’s lobbying paid off: voters rejected the charge in the local referendum and the proposal was dropped.

Throughout England, cash-strapped councils are being outgunned by corporate developers pressing to get their way. The situation is exacerbated by a system that has allowed companies like Peel to keep their corporate structures obscure and their landholdings hidden. A 2013 report by Liverpool-based thinktank Ex Urbe found “well in excess of 300 separately registered UK companies owned or controlled” by Peel. Tracing the conglomerate’s structure is an investigator’s nightmare. Try it yourself on the Companies House website: type in “Peel Land and Property Investments PLC”, and then click through to persons with significant control. This gives you the name of its parent company, Peel Investments Holdings Ltd. So far, so good. But then repeat the steps for the parent company, and yet another holding company emerges; then another, and another. It’s like a series of Russian dolls, one nested inside another.

Until recently, it was even harder to get a handle on the land Peel Holdings owns. Sometimes the company has provided a tantalising glimpse: one map it produced in 2015, as part of some marketing spiel around the “northern powerhouse”, showcases 150 sites it owns across the north-west. It confirms the vast spread of Peel’s landed interests – from Liverpool John Lennon airport, through shale gas well pads, to one of the UK’s largest onshore wind farms. But it’s clearly not everything. A more exhaustive, independent list of the company’s landholdings might allow communities to be forewarned of future developments. As Ex Urbe’s report on Peel concludes: “Peel schemes rarely come to light until they are effectively a fait accompli and the conglomerate is confident they will go ahead, irrespective of public opinion.”

While Peel Holdings is unusual for the sheer amount of land it controls, it is also illustrative of corporate landowners everywhere. Corporations looking to develop land have numerous tricks up their sleeve that they can use to evade scrutiny and get their way, from shell company structures to offshore entities. Companies with big enough budgets can often ride roughshod over the planning system, beating cash-strapped councils and volunteer community groups. And companies have for a long time benefited from having their landholdings kept secret, giving them the element of surprise when it comes to lobbying councils over planning decisions and the use of public space. But now, at long last, that is starting to change. If we want to “take back control” of our country, we need to understand how much of it is currently controlled by corporations.

In 2015, the Private Eye journalist Christian Eriksson lodged a freedom of information (FOI) request with the Land Registry, the official record of land ownership in England and Wales. He asked it to release a database detailing the area of land owned by all UK-registered companies and corporate bodies. Eriksson later shared this database with me, and what it revealed was astonishing. Here, laid bare after the dataset had been cleaned up, was a picture of corporate control: companies today own about 2.6m hectares of land, or roughly 18% of England and Wales.

In the unpromising format of an Excel spreadsheet, a compelling picture emerged. Alongside the utilities privatised by Margaret Thatcher and John Major – the water companies, in particular – and the big corporate landowners, were PLCs with multiple shareholders. There were household names, such as Tesco, Tata Steel and the housebuilder Taylor Wimpey, and others more obscure. MRH Minerals, for example, appeared to own 28,000 hectares of land, making it one of the biggest corporate landowners in England and Wales.

Gradually, I pieced together a list of what looked to be the top 50 landowning companies, which together own more than 405,000 hectares of England and Wales. Peel Holdings and many of its subsidiaries, unsurprisingly, feature high on the list. But while the dataset revealed in stark detail the area of land owned by UK-based companies, it did nothing to tell us what they owned, and where.

That would take another two years to emerge. Meanwhile, Eriksson had been busy at work with his Private Eye colleague Richard Brooks and the computer programmer Anna Powell-Smith, delving into another form of corporate landowner – firms based overseas, yet owning land in the UK. Of particular interest were companies based in offshore tax havens, a wholly legal but controversial practice, given the opportunities offshore ownership gives for possible tax avoidance and for concealing the identities of who ultimately controls a company. Further FOI requests to the Land Registry by Eriksson hit the jackpot when he was sent – “accidentally”, the Land Registry would later claim – a huge dataset of overseas and offshore-registered companies that had bought land in England and Wales between 2005 and 2014: some 113,119 hectares of land and property, worth a staggering £170bn.

Victoria Harbour building at Salford Quays, owned by Peel Holdings. Photograph: Mike Robinson/Alamy

Private Eye’s work revealed that a large chunk of the country was not only under corporate control, but owned by companies that – in many cases – were almost certainly seeking to avoid paying tax, that most basic contribution to a civilised society. Some potentially had an even darker motive: purchasing property in England or Wales as a means for kleptocratic regimes or corrupt businessmen to launder money, and to get a healthy return on their ill-gotten gains in the process. This was information that clearly ought to be out in the open, with a huge public interest case for doing so. And yet the government had sat on it for years.

The political ramifications of these revelations were profound. They kickstarted a process of opening up information on land ownership that, although far slower and less complete than many would have liked, has nevertheless transformed our understanding of what companies own. In November 2017, the Land Registry released its corporate and commercial dataset, free of charge and open to all. It revealed, for the first time, the 3.5m land titles owned by UK-based corporate bodies – covering both public sector institutions and private firms – with limited companies owning the majority, 2.1m, of these. But there were two important caveats. Although we now had the addresses owned by companies, the dataset omitted to tell us the size of land they owned. Second, the data lacked accurate information on locations, making it hard to map.

Despite this, what can we now say about company-owned land in England and Wales? Quite a lot, it turns out. We know, for example, that the company with the third-highest number of land titles is the mysterious Wallace Estates, a firm with a £200m property portfolio but virtually no public presence, and which is owned ultimately by a secretive Italian count. Wallace Estates makes its money from the controversial ground rents market, whereby it owns thousands of freehold properties and sells on long leases with annual ground rents.

We also now know that Peel Holdings and its numerous subsidiaries owns at least 1,000 parcels of land across England – not just shopping centres and ports in the north-west, but also a hill in Suffolk, farmland along the Medway and an industrial estate in the Cotswolds. Councils, MPs and residents wanting to keep an eye on what developers and property companies are up to in their area now have a powerful new tool at their disposal.

The data is full of odd quirks and details. Who would have guessed, for instance, that the arms manufacturer BAE owns a nightclub in Cardiff, a pub on Blackpool’s promenade and a service station in Pease Pottage, Sussex? It turns out that they are all investments made by BAE’s pension fund; if selling missiles to Saudi Arabia doesn’t prove profitable enough, it appears the company’s strategy is to make a few quid out of tired drivers stopping for a coffee break off the M23.

The data also lets us peer into the property acquisitions of the big supermarkets, which back in the 1990s and early 2000s involved building up huge land banks to construct ever more out-of-town retail parks. Tesco, via a welter of subsidiaries, owns more than 4,500 hectares of land – and although much of this comprises existing stores, a good chunk also appears to be empty plots, apparently earmarked for future development. One analysis by the Guardian in 2014 estimated that the supermarket was hoarding enough land to accommodate 15,000 homes. More recently, however, Tesco’s financial travails have prompted it to sell off some of its sites. Internet shopping and pricier petrol have made giant hypermarkets built miles from where people live look less and less like smart investments. In 2016, Tesco’s beleaguered CEO announced the company was looking to make better use of the land it owned by selling it for housing, and even by building flats on top of its superstores. As for the supermarkets’ internet shopping rival Amazon, whose gigantic “fulfilment centres” resemble the vast US government warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark – well, Amazon currently has 16 of those across the UK. And it has grown very quickly: all but one of its property leases have been bought in the past decade.

Companies are increasingly taking over previously public space in cities, too. Recent years have seen a proliferation of Pops – privately owned public spaces – as London, Manchester and other places redevelop and gentrify. You know the sort of thing: expensively landscaped swaths of “public realm”. Aesthetically, they are all very nice, but try to use Pops for some peaceful protest, and you are in for trouble. They are invariably governed by special bylaws and policed by private security, itching to get in your face. I once found this to my cost when staging a tiny, two-person anti-fracking demo outside shale-gas financiers Barclays bank in Canary Wharf. Canary Wharf is partly owned by the Qatari Investment Authority, and – bizarrely – photography is banned. Within a minute of us taking the first selfie on our innocuous protest, security guards had descended en masse, and we spent the next hour running around Canary Wharf trying to evade them.

The Land Registry’s corporate ownership dataset contains millions of entries, and much remains to be uncovered. Some of the information appears trivial at first glance – a company owns a factory here, an office there: so what? But as more people pore over the data, more stories will likely emerge. Future researchers might find intriguing correlations between the locations of England’s thousands of fast-food stores and the health of nearby populations, be able to track gentrification through the displacement of KFC outlets by Nando’s restaurants, and so on.

But to really get under the skin of how companies treat the land they own, and the wider repercussions, we need to zoom in on the housing sector, where debates about companies involved in land banking and profiteering from land sales are crucial to our understanding of the housing crisis.

One particularly controversial aspect of the housing debate that has generated much heat, and little light, in recent years is the debacle over land banking, the practice of hoarding land and holding it back from development until its price increases.

In 2016, the then housing secretary, Sajid Javid, furiously accused large housing developers of land banking and demanded they “release their stranglehold” on land supply. Housebuilders, not used to such impertinence from a Conservative minister, hit back. “As has been proved by various investigations in the past, housebuilders do not land bank,” a spokesperson for the Home Builders Federation told the Telegraph. “In the current market where demand is high, there is absolutely no reason to do so.”

So who is right? This is a complex area, but one that is important to investigate. Can the Land Registry’s corporate ownership data help us get to the bottom of it?

It is common for UK pension funds and insurance companies to buy up land as a long-term strategic investment. Legal & General, for example, owns 1,500 hectares of land that it openly calls a “strategic land portfolio … stretching from Luton to Cardiff”. Its rationale for buying land is simple: “Strategic land holdings are underpinned by their existing use value [such as farming] and give us the opportunity to create further value through planning promotion and infrastructure works over the medium to long term.”

When I looked into where Legal & General’s land was located, I noticed something odd. Nearly all of it lay within green belt areas, where development is restricted. The company appears to have bought it with the aim of lobbying councils to ultimately rip up such restrictions and redesignate the site for development in future.

In the case of pension funds lobbying to rip up the green belt, it’s the planning system that is (rightly) constraining development, not land banking itself. And none of this implicates the usual bogeymen of the housing crisis, the big housebuilding companies. By examining what these major developers own, is it possible to say whether they’re actively engaged in land banking?

There is no doubt that many of the major housebuilding companies own a lot of land. What’s more, housing developers themselves talk about their “current land banks” and publish figures in annual reports listing the number of homes they think they can build using land where they have planning permission. As the housing charity Shelter has found, the top 10 housing developers have land banks with space for more than 400,000 homes – about six years’ supply at current building rates.

Prompted by such statistics, the government ordered a review into build-out rates in 2017, led by Sir Oliver Letwin. Yet when Letwin delivered his draft report, he once again exonerated housebuilders from the charge of land banking. “I cannot find any evidence that the major housebuilders are financial investors of this kind,” he stated, pointing the finger of blame instead at the rate at which new homes could be absorbed into the marketplace.

Part of the problem is that the data on what companies own still isn’t good enough to prove whether or not land banking is occurring. The aforementioned Anna Powell-Smith has tried to map the land owned by housing developers, but has been thwarted by the lack in the Land Registry’s corporate dataset of the necessary information to link data on who owns a site with digital maps of that area. That makes it very hard to assess, for example, whether a piece of land owned by a housebuilder for decades is a prime site accruing in value or a leftover fragment of ground from a past development.

Private Eye’s work revealed that a large chunk of the country was not only under corporate control, but owned by companies that – in many cases – were almost certainly seeking to avoid paying tax, that most basic contribution to a civilised society. Some potentially had an even darker motive: purchasing property in England or Wales as a means for kleptocratic regimes or corrupt businessmen to launder money, and to get a healthy return on their ill-gotten gains in the process. This was information that clearly ought to be out in the open, with a huge public interest case for doing so. And yet the government had sat on it for years.

The political ramifications of these revelations were profound. They kickstarted a process of opening up information on land ownership that, although far slower and less complete than many would have liked, has nevertheless transformed our understanding of what companies own. In November 2017, the Land Registry released its corporate and commercial dataset, free of charge and open to all. It revealed, for the first time, the 3.5m land titles owned by UK-based corporate bodies – covering both public sector institutions and private firms – with limited companies owning the majority, 2.1m, of these. But there were two important caveats. Although we now had the addresses owned by companies, the dataset omitted to tell us the size of land they owned. Second, the data lacked accurate information on locations, making it hard to map.

Despite this, what can we now say about company-owned land in England and Wales? Quite a lot, it turns out. We know, for example, that the company with the third-highest number of land titles is the mysterious Wallace Estates, a firm with a £200m property portfolio but virtually no public presence, and which is owned ultimately by a secretive Italian count. Wallace Estates makes its money from the controversial ground rents market, whereby it owns thousands of freehold properties and sells on long leases with annual ground rents.

We also now know that Peel Holdings and its numerous subsidiaries owns at least 1,000 parcels of land across England – not just shopping centres and ports in the north-west, but also a hill in Suffolk, farmland along the Medway and an industrial estate in the Cotswolds. Councils, MPs and residents wanting to keep an eye on what developers and property companies are up to in their area now have a powerful new tool at their disposal.

The data is full of odd quirks and details. Who would have guessed, for instance, that the arms manufacturer BAE owns a nightclub in Cardiff, a pub on Blackpool’s promenade and a service station in Pease Pottage, Sussex? It turns out that they are all investments made by BAE’s pension fund; if selling missiles to Saudi Arabia doesn’t prove profitable enough, it appears the company’s strategy is to make a few quid out of tired drivers stopping for a coffee break off the M23.

The data also lets us peer into the property acquisitions of the big supermarkets, which back in the 1990s and early 2000s involved building up huge land banks to construct ever more out-of-town retail parks. Tesco, via a welter of subsidiaries, owns more than 4,500 hectares of land – and although much of this comprises existing stores, a good chunk also appears to be empty plots, apparently earmarked for future development. One analysis by the Guardian in 2014 estimated that the supermarket was hoarding enough land to accommodate 15,000 homes. More recently, however, Tesco’s financial travails have prompted it to sell off some of its sites. Internet shopping and pricier petrol have made giant hypermarkets built miles from where people live look less and less like smart investments. In 2016, Tesco’s beleaguered CEO announced the company was looking to make better use of the land it owned by selling it for housing, and even by building flats on top of its superstores. As for the supermarkets’ internet shopping rival Amazon, whose gigantic “fulfilment centres” resemble the vast US government warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark – well, Amazon currently has 16 of those across the UK. And it has grown very quickly: all but one of its property leases have been bought in the past decade.

Companies are increasingly taking over previously public space in cities, too. Recent years have seen a proliferation of Pops – privately owned public spaces – as London, Manchester and other places redevelop and gentrify. You know the sort of thing: expensively landscaped swaths of “public realm”. Aesthetically, they are all very nice, but try to use Pops for some peaceful protest, and you are in for trouble. They are invariably governed by special bylaws and policed by private security, itching to get in your face. I once found this to my cost when staging a tiny, two-person anti-fracking demo outside shale-gas financiers Barclays bank in Canary Wharf. Canary Wharf is partly owned by the Qatari Investment Authority, and – bizarrely – photography is banned. Within a minute of us taking the first selfie on our innocuous protest, security guards had descended en masse, and we spent the next hour running around Canary Wharf trying to evade them.

The Land Registry’s corporate ownership dataset contains millions of entries, and much remains to be uncovered. Some of the information appears trivial at first glance – a company owns a factory here, an office there: so what? But as more people pore over the data, more stories will likely emerge. Future researchers might find intriguing correlations between the locations of England’s thousands of fast-food stores and the health of nearby populations, be able to track gentrification through the displacement of KFC outlets by Nando’s restaurants, and so on.

But to really get under the skin of how companies treat the land they own, and the wider repercussions, we need to zoom in on the housing sector, where debates about companies involved in land banking and profiteering from land sales are crucial to our understanding of the housing crisis.

One particularly controversial aspect of the housing debate that has generated much heat, and little light, in recent years is the debacle over land banking, the practice of hoarding land and holding it back from development until its price increases.

In 2016, the then housing secretary, Sajid Javid, furiously accused large housing developers of land banking and demanded they “release their stranglehold” on land supply. Housebuilders, not used to such impertinence from a Conservative minister, hit back. “As has been proved by various investigations in the past, housebuilders do not land bank,” a spokesperson for the Home Builders Federation told the Telegraph. “In the current market where demand is high, there is absolutely no reason to do so.”

So who is right? This is a complex area, but one that is important to investigate. Can the Land Registry’s corporate ownership data help us get to the bottom of it?

It is common for UK pension funds and insurance companies to buy up land as a long-term strategic investment. Legal & General, for example, owns 1,500 hectares of land that it openly calls a “strategic land portfolio … stretching from Luton to Cardiff”. Its rationale for buying land is simple: “Strategic land holdings are underpinned by their existing use value [such as farming] and give us the opportunity to create further value through planning promotion and infrastructure works over the medium to long term.”

When I looked into where Legal & General’s land was located, I noticed something odd. Nearly all of it lay within green belt areas, where development is restricted. The company appears to have bought it with the aim of lobbying councils to ultimately rip up such restrictions and redesignate the site for development in future.

In the case of pension funds lobbying to rip up the green belt, it’s the planning system that is (rightly) constraining development, not land banking itself. And none of this implicates the usual bogeymen of the housing crisis, the big housebuilding companies. By examining what these major developers own, is it possible to say whether they’re actively engaged in land banking?

There is no doubt that many of the major housebuilding companies own a lot of land. What’s more, housing developers themselves talk about their “current land banks” and publish figures in annual reports listing the number of homes they think they can build using land where they have planning permission. As the housing charity Shelter has found, the top 10 housing developers have land banks with space for more than 400,000 homes – about six years’ supply at current building rates.

Prompted by such statistics, the government ordered a review into build-out rates in 2017, led by Sir Oliver Letwin. Yet when Letwin delivered his draft report, he once again exonerated housebuilders from the charge of land banking. “I cannot find any evidence that the major housebuilders are financial investors of this kind,” he stated, pointing the finger of blame instead at the rate at which new homes could be absorbed into the marketplace.

Part of the problem is that the data on what companies own still isn’t good enough to prove whether or not land banking is occurring. The aforementioned Anna Powell-Smith has tried to map the land owned by housing developers, but has been thwarted by the lack in the Land Registry’s corporate dataset of the necessary information to link data on who owns a site with digital maps of that area. That makes it very hard to assess, for example, whether a piece of land owned by a housebuilder for decades is a prime site accruing in value or a leftover fragment of ground from a past development.

Shoppers in the Trafford Centre, a shopping mall until recently owned by Peel Holdings. Photograph: Oli Scarff/AFP/Getty

Second, the scope of Letwin’s review was drawn too narrowly to examine the wider problem of land banking by landowners beyond the major housebuilders. As the housing market analyst Neal Hudson said when it was published, the “review remit ignored the most important and unknown bit of the market: sites and land ownership pre-planning.”