“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Thursday 6 December 2018

Wednesday 5 December 2018

‘An education arms race’: inside the ultra-competitive world of private tutoring

A growing number of parents and guardians are paying for children as young as four to receive additional tuition. What is fuelling this booming industry asks Sally Weale in The Guardian?

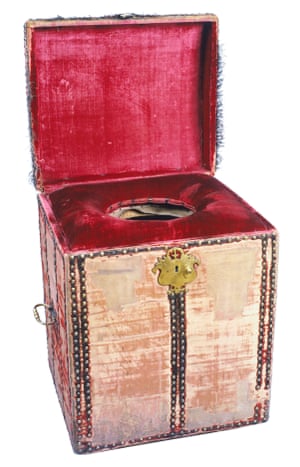

‘I’m trying to do something for him that I never got’ ... Geoff Clayton, Brooklyn’s grandfather. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/Christopher Thomond/Guardian

“The world is very competitive and everybody is working very hard,” said Ijaz. “I know the school are doing very well, but there are 30 students in each class. It’s one teacher and support staff. They try their best to help, but I realise if I’m going to give my kids some extra help it’s going to be brilliant for their future. Anyone who does a bit extra always gets ahead.”

He is ambitious for his children. “I warn my kids they should be top – or among the top five at least – in class. They are doing well. I don’t mind paying extra. I’m investing in their future. I know the importance of education. My kids love it.”

Abubakar, a quiet, serious child, is planning to sit the 11-plus to win a place at grammar school. Sometimes he does not feel like starting work, “but when I’ve started I like to carry on”. Amna is a chatty livewire and wants to be a paleontologist. “I’m good at maths, but the thing I’m best at is history,” she chirps. “My brother does hard work. I’m doing the same now. I want to be the same as him.”

Geoff Clayton, a retired garage worker, has been bringing his 10-year-old grandson, Brooklyn, to Explore Learning for about nine months. Brooklyn lives with his grandparents and likes football, Minecraft and maths. “He’s done really well,” says Clayton. “His reading has got a lot better, everything’s got better.” The membership takes a significant chunk out of his pension, but he is happy to pay it to give Brooklyn “a bit of a leg up”.

“Nowadays, it’s all about exams and certificates and what you know,” he says. “When I left school, it was more: ‘Can you do the job?’ Brooklyn has done a heck of a lot better since coming here. Sometimes he moans, but he’s OK once he’s here. It does work if you’re prepared to put the time and effort in.”

The Sutton Trust, a charity that seeks to improve social mobility through education, has documented a huge rise in private tuition in recent years. Its annual survey of secondary students in England and Wales revealed in July that 27% have had home or private tuition, a figure that rises to 41% in London.

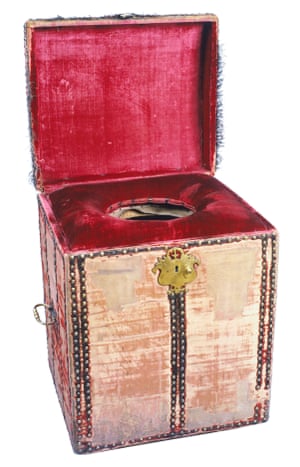

The Bradford outpost of Explore Learning, which now has 139 centres across the UK. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/Christopher Thomond/Guardian

With tutoring commanding a fee of about £24 an hour, rising to £27 in London (although many tutors charge £60 or more), the trust is concerned that the private tuition market is putting children from poorer backgrounds at even greater disadvantage. To redress the balance, it would like to see the government introduce a means-tested voucher system, paid for through the pupil premium funding that schools receive to support disadvantaged pupils.

“We are in an education arms race,” says Peter Lampl, the founder of the trust. “Parents are looking to get an edge for their kids and having private tuition gives them that edge. But if we are serious about social mobility, we need to make sure that the academic playing field is levelled outside the school gate.”

Initiatives aimed at making tuition more accessible already exist: some agencies pledge a proportion of their tuition to poorer pupils for free, while non-profit programmes such as the Tutor Trust connect tutors with disadvantaged schools. Explore Learning offers “scholarships” that give a 50% discount to parents on income support or jobseeker’s allowance. Parents can also use childcare vouchers and tax-free childcare schemes to help pay for tuition.

Nevertheless, huge inequities in education persist. Nowhere is this more evident than in children’s battle to pass the 11-plus to get into grammar school. Research published earlier this year revealed that private tutoring means pupils from high-income families are much more likely to get into grammar schools than equally bright pupils from poorer families. John Jerrim and Sam Sims from the Institute of Education at University College London looked at more than 1,800 children in areas where the grammar school system is in operation. They found that those from families in the bottom quarter of household incomes in England have less than a 10% chance of attending a grammar school, compared with a 40% chance for children in the top quarter.

If we are serious about social mobility, we need to make sure the academic playing field is levelled outside school - Peter Lampl, the Sutton Trust

They also established that wealthier families are much more likely to use private tutors to prepare their children for the entrance exam. Fewer than 10% of children from families with below-average incomes received coaching, compared with about 30% from households in the top quarter. About 70% of those who received tutoring got into a grammar school, compared with 14% of those who did not.

Alexa Collins lives in Buckinghamshire, which operates a grammar school system. She could not afford tuition to prepare her daughter for the 11-plus; despite being a top performer at primary, she failed the test, but has since thrived at her comprehensive, gaining nine GCSEs.

Collins, who went to grammar school herself but received no coaching, says she is ideologically opposed to tutoring because it is unfair to those who cannot afford it. Although she can see the case for short-term tutoring on a specific subject when a child is struggling, she adds: “I think it’s awful, that idea of tutoring kids from seven to push them through this exam. How can you possibly put that pressure on them?”

Another parent, who wishes to remain anonymous but lives in Kent, which operates grammar schools, says her son tackled the 11-plus without a tutor. “It felt morally wrong to claim an advantage by paying cash. It’s so unfair.” As she tried to coach her son, she felt at huge disadvantage. “So much depends on a parent’s skills to teach. A tutor would know the best way to teach the 11-plus concepts. I was terrible at maths at school, so I was really stuck.”

“The government claims that expanding grammars will boost social mobility,” said Jerrim, a professor of education and social statistics at UCL, when the research was published. “But our research shows that private tuition used by high-income families gives them a big advantage in getting in.” One of the factors behind the increase in tuition, he says now, is the pressure exerted by school league tables and growing accountability measures. “Those schools might well be passing pressure on to parents,” he says. “It’s not a negative reflection on schools and the job that they are doing; it’s more a reflection of the pressure they are under to achieve results.”

A callout asking Guardian readers about their experiences of tuition drew hundreds of responses from tutors, parents and school teachers. One tutor told of being approached by parents of children as young as three or four; another had been hired to provide extra coaching for pupils whose parents were already paying for all of the privileges of private schools, including Marlborough and Eton. “We pay thousands of pounds a year on school fees,” said one parent. “If he needs a little help with certain subjects, why wouldn’t you help him?” There also appears to be a trend for university students to buy extra tuition. Most are already paying £9,250 a year in tuition fees, so why not spend a little more to ensure they get the best possible degree?

The Profs, which launched in 2014, specialises in degree-level and professional-qualification tutoring. According to its website, an undergraduate teacher with a master’s in the required subject costs upwards of £70 an hour (plus a £50 placement fee); tutors specialising in applications to Oxbridge and Ivy League universities start at £120 an hour, plus a £250 consultation fee. According to Leo Evans, one of the founders of The Profs, university lecturers can struggle to address individual learning difficulties. “Catching stragglers and helping them get on top of their studies is a useful social function. Also, for students with disabilities and impairments, it’s essential.”

I don’t mind paying extra. I’m investing in their future’ ... Malik Ijaz and his wife, Ayesha, bring a son and a daughter to the Bradford classes. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/Guardian

Other responses to our callout came from parents who were worried about schools’ increasingly limited resources due to budget cuts. Much of the additional support that was once available in classrooms is disappearing and some specialist teachers are in short supply. These parents see tutoring as a way of patching the gaps in their children’s education. “It’s only one hour a week, but the practice crammed into that time is like a full week of lessons at school,” said one parent, who is a teacher. “The ability to check every week how well the information is being retained is great. It also provides ‘real-time’ feedback that we don’t get from schools.”

Some parents buy extra tuition to support children with special educational needs such as dyslexia, which mainstream schools are increasingly unable to meet. The new, tougher GCSE exams are also a factor, with some parents hiring private tutors to help children who are struggling to secure the level 4 or above required in English and maths.

One mother from Nigeria said she sought extra support for her child as a practical response to racial discrimination: “Any child from a minority has to be many times better than their white counterparts to be able to get into the top schools and universities.” Another parent told of a daughter with cancer who missed a year of formal education, but got through with the help of a tutor. Another respondent claimed the shadow tutoring workforce “props up” some “outstanding” schools – private, grammar and state.

Not everyone was positive about the impact of tuition. “It can cause students to not work in lessons,” said one teacher. Another said: “The need for tutoring frightens me. Schools should be able to offer students the support they need in class sizes that are manageable.” While one parent said: “I resent it when having a tutor is seen as a class crime,” another acknowledged the unfairness at the heart of the system: “I feel uncomfortable that we can afford to pay for this privilege.”

The callout also revealed the appeal of private tuition for teachers, whose salaries have been depressed for years while the demands upon them have grown. Some said they did private tutoring to boost their income; others, tired of the one-size-fits-all approach in schools, have quit their jobs to do it full time.

Asked about the boom in private tuition, the Department for Education responded that standards are rising in schools and that the attainment gap between rich and poor pupils is shrinking. “While we believe families shouldn’t have to pay for private tuition, it has always been part of the system and parents have freedom to do this,” a spokesman said.

“Tutoring is huge, it’s getting bigger and it’s not going away,” says the Sutton Trust’s Lampl. “You can’t stop people from doing it. What we’ve got to do is make it more accessible for parents who currently can’t afford it.”

Clayton, the retired garage worker from Bradford, is not a rich man, but he wants to invest what he has in his grandson’s future. His hopes for Brooklyn are modest and honourable and shared by parents and grandparents everywhere. “I want Brooklyn to have a good start in life … Nobody gave me a leg up. I’m trying to do something for him that I never got. I hope he ends up being a decent person when he grows up and gets a decent job and doesn’t have to struggle.”

As dusk falls in the Girlington district of Bradford, a trickle of cars begin to arrive in front of a small parade of shops. Parents who have just collected their children at the end of the school day are dropping them off at the Explore Learning tuition centre for extra maths and English coaching. The children sit at a cluster of computer terminals, where they log in to begin their evening studies. The atmosphere is relaxed and lighthearted. The children stay for an hour to work through their lessons, helped where necessary by a member of staff, with 15 minutes’ playtime at the end.

Located next to a Domino’s and a Subway, the Bradford branch of Explore Learning is a tiny window into Britain’s booming private tuition sector, now worth an estimated £2bn. At one time, private tuition meant a weekly one-to-one session at home with a tutor, the preserve of the privileged few. It is still not cheap – Explore Learning’s standard membership costs £119 a month, plus a £50 registration fee – but it is now on offer on our high streets, in supermarkets and increasingly online, with tutors offering their services from as far afield as India and Sri Lanka. Tutees include children who are little older than toddlers, pupils at prestigious private schools and undergraduates struggling at university. All are caught up in an educational arms race, which experts say is exacerbating social inequality.

The success of Explore Learning reflects some of these changes. The business was founded in 2001 by Bill Mills, a Cambridge maths graduate, and now has 139 centres around the country (plus five in Texas run by a sister company). They are located mainly in shopping centres, so busy parents can get on with their weekly shop while their offspring perfect their times tables, punctuation and grammar. Most of the children, who are aged four to 14, come at least a couple of times a week – the membership allows for up to nine sessions a month. Saturday and Sunday afternoons are the busiest times in the Bradford branch, which has 290 children on its books. The tutor-tutee ratio is one to six, but the tutors are not usually qualified teachers; they may be students or mothers returning to the workplace. All are trained in the teaching materials and behaviour management.

The families who use the centre come from various walks of life. Some parents have their own businesses; others work at Bradford Royal Infirmary. There are families from Latvia, Poland and the Philippines. The parents talk about giving their children “an edge”, the “leg up” they never had. Among them are a shift worker, Malik Ijaz, and his wife, Ayesha, who have been bringing nine-year-old Abubakar and his seven-year-old sister, Amna, to the centre for nearly two years. It is a big expense for the family, but the children’s education is a priority. Ijaz works extra shifts to be able to afford it. A third child, four-year-old Ali, will come when he is older.

Located next to a Domino’s and a Subway, the Bradford branch of Explore Learning is a tiny window into Britain’s booming private tuition sector, now worth an estimated £2bn. At one time, private tuition meant a weekly one-to-one session at home with a tutor, the preserve of the privileged few. It is still not cheap – Explore Learning’s standard membership costs £119 a month, plus a £50 registration fee – but it is now on offer on our high streets, in supermarkets and increasingly online, with tutors offering their services from as far afield as India and Sri Lanka. Tutees include children who are little older than toddlers, pupils at prestigious private schools and undergraduates struggling at university. All are caught up in an educational arms race, which experts say is exacerbating social inequality.

The success of Explore Learning reflects some of these changes. The business was founded in 2001 by Bill Mills, a Cambridge maths graduate, and now has 139 centres around the country (plus five in Texas run by a sister company). They are located mainly in shopping centres, so busy parents can get on with their weekly shop while their offspring perfect their times tables, punctuation and grammar. Most of the children, who are aged four to 14, come at least a couple of times a week – the membership allows for up to nine sessions a month. Saturday and Sunday afternoons are the busiest times in the Bradford branch, which has 290 children on its books. The tutor-tutee ratio is one to six, but the tutors are not usually qualified teachers; they may be students or mothers returning to the workplace. All are trained in the teaching materials and behaviour management.

The families who use the centre come from various walks of life. Some parents have their own businesses; others work at Bradford Royal Infirmary. There are families from Latvia, Poland and the Philippines. The parents talk about giving their children “an edge”, the “leg up” they never had. Among them are a shift worker, Malik Ijaz, and his wife, Ayesha, who have been bringing nine-year-old Abubakar and his seven-year-old sister, Amna, to the centre for nearly two years. It is a big expense for the family, but the children’s education is a priority. Ijaz works extra shifts to be able to afford it. A third child, four-year-old Ali, will come when he is older.

‘I’m trying to do something for him that I never got’ ... Geoff Clayton, Brooklyn’s grandfather. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/Christopher Thomond/Guardian

“The world is very competitive and everybody is working very hard,” said Ijaz. “I know the school are doing very well, but there are 30 students in each class. It’s one teacher and support staff. They try their best to help, but I realise if I’m going to give my kids some extra help it’s going to be brilliant for their future. Anyone who does a bit extra always gets ahead.”

He is ambitious for his children. “I warn my kids they should be top – or among the top five at least – in class. They are doing well. I don’t mind paying extra. I’m investing in their future. I know the importance of education. My kids love it.”

Abubakar, a quiet, serious child, is planning to sit the 11-plus to win a place at grammar school. Sometimes he does not feel like starting work, “but when I’ve started I like to carry on”. Amna is a chatty livewire and wants to be a paleontologist. “I’m good at maths, but the thing I’m best at is history,” she chirps. “My brother does hard work. I’m doing the same now. I want to be the same as him.”

Geoff Clayton, a retired garage worker, has been bringing his 10-year-old grandson, Brooklyn, to Explore Learning for about nine months. Brooklyn lives with his grandparents and likes football, Minecraft and maths. “He’s done really well,” says Clayton. “His reading has got a lot better, everything’s got better.” The membership takes a significant chunk out of his pension, but he is happy to pay it to give Brooklyn “a bit of a leg up”.

“Nowadays, it’s all about exams and certificates and what you know,” he says. “When I left school, it was more: ‘Can you do the job?’ Brooklyn has done a heck of a lot better since coming here. Sometimes he moans, but he’s OK once he’s here. It does work if you’re prepared to put the time and effort in.”

The Sutton Trust, a charity that seeks to improve social mobility through education, has documented a huge rise in private tuition in recent years. Its annual survey of secondary students in England and Wales revealed in July that 27% have had home or private tuition, a figure that rises to 41% in London.

The Bradford outpost of Explore Learning, which now has 139 centres across the UK. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/Christopher Thomond/Guardian

With tutoring commanding a fee of about £24 an hour, rising to £27 in London (although many tutors charge £60 or more), the trust is concerned that the private tuition market is putting children from poorer backgrounds at even greater disadvantage. To redress the balance, it would like to see the government introduce a means-tested voucher system, paid for through the pupil premium funding that schools receive to support disadvantaged pupils.

“We are in an education arms race,” says Peter Lampl, the founder of the trust. “Parents are looking to get an edge for their kids and having private tuition gives them that edge. But if we are serious about social mobility, we need to make sure that the academic playing field is levelled outside the school gate.”

Initiatives aimed at making tuition more accessible already exist: some agencies pledge a proportion of their tuition to poorer pupils for free, while non-profit programmes such as the Tutor Trust connect tutors with disadvantaged schools. Explore Learning offers “scholarships” that give a 50% discount to parents on income support or jobseeker’s allowance. Parents can also use childcare vouchers and tax-free childcare schemes to help pay for tuition.

Nevertheless, huge inequities in education persist. Nowhere is this more evident than in children’s battle to pass the 11-plus to get into grammar school. Research published earlier this year revealed that private tutoring means pupils from high-income families are much more likely to get into grammar schools than equally bright pupils from poorer families. John Jerrim and Sam Sims from the Institute of Education at University College London looked at more than 1,800 children in areas where the grammar school system is in operation. They found that those from families in the bottom quarter of household incomes in England have less than a 10% chance of attending a grammar school, compared with a 40% chance for children in the top quarter.

If we are serious about social mobility, we need to make sure the academic playing field is levelled outside school - Peter Lampl, the Sutton Trust

They also established that wealthier families are much more likely to use private tutors to prepare their children for the entrance exam. Fewer than 10% of children from families with below-average incomes received coaching, compared with about 30% from households in the top quarter. About 70% of those who received tutoring got into a grammar school, compared with 14% of those who did not.

Alexa Collins lives in Buckinghamshire, which operates a grammar school system. She could not afford tuition to prepare her daughter for the 11-plus; despite being a top performer at primary, she failed the test, but has since thrived at her comprehensive, gaining nine GCSEs.

Collins, who went to grammar school herself but received no coaching, says she is ideologically opposed to tutoring because it is unfair to those who cannot afford it. Although she can see the case for short-term tutoring on a specific subject when a child is struggling, she adds: “I think it’s awful, that idea of tutoring kids from seven to push them through this exam. How can you possibly put that pressure on them?”

Another parent, who wishes to remain anonymous but lives in Kent, which operates grammar schools, says her son tackled the 11-plus without a tutor. “It felt morally wrong to claim an advantage by paying cash. It’s so unfair.” As she tried to coach her son, she felt at huge disadvantage. “So much depends on a parent’s skills to teach. A tutor would know the best way to teach the 11-plus concepts. I was terrible at maths at school, so I was really stuck.”

“The government claims that expanding grammars will boost social mobility,” said Jerrim, a professor of education and social statistics at UCL, when the research was published. “But our research shows that private tuition used by high-income families gives them a big advantage in getting in.” One of the factors behind the increase in tuition, he says now, is the pressure exerted by school league tables and growing accountability measures. “Those schools might well be passing pressure on to parents,” he says. “It’s not a negative reflection on schools and the job that they are doing; it’s more a reflection of the pressure they are under to achieve results.”

A callout asking Guardian readers about their experiences of tuition drew hundreds of responses from tutors, parents and school teachers. One tutor told of being approached by parents of children as young as three or four; another had been hired to provide extra coaching for pupils whose parents were already paying for all of the privileges of private schools, including Marlborough and Eton. “We pay thousands of pounds a year on school fees,” said one parent. “If he needs a little help with certain subjects, why wouldn’t you help him?” There also appears to be a trend for university students to buy extra tuition. Most are already paying £9,250 a year in tuition fees, so why not spend a little more to ensure they get the best possible degree?

The Profs, which launched in 2014, specialises in degree-level and professional-qualification tutoring. According to its website, an undergraduate teacher with a master’s in the required subject costs upwards of £70 an hour (plus a £50 placement fee); tutors specialising in applications to Oxbridge and Ivy League universities start at £120 an hour, plus a £250 consultation fee. According to Leo Evans, one of the founders of The Profs, university lecturers can struggle to address individual learning difficulties. “Catching stragglers and helping them get on top of their studies is a useful social function. Also, for students with disabilities and impairments, it’s essential.”

I don’t mind paying extra. I’m investing in their future’ ... Malik Ijaz and his wife, Ayesha, bring a son and a daughter to the Bradford classes. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/Guardian

Other responses to our callout came from parents who were worried about schools’ increasingly limited resources due to budget cuts. Much of the additional support that was once available in classrooms is disappearing and some specialist teachers are in short supply. These parents see tutoring as a way of patching the gaps in their children’s education. “It’s only one hour a week, but the practice crammed into that time is like a full week of lessons at school,” said one parent, who is a teacher. “The ability to check every week how well the information is being retained is great. It also provides ‘real-time’ feedback that we don’t get from schools.”

Some parents buy extra tuition to support children with special educational needs such as dyslexia, which mainstream schools are increasingly unable to meet. The new, tougher GCSE exams are also a factor, with some parents hiring private tutors to help children who are struggling to secure the level 4 or above required in English and maths.

One mother from Nigeria said she sought extra support for her child as a practical response to racial discrimination: “Any child from a minority has to be many times better than their white counterparts to be able to get into the top schools and universities.” Another parent told of a daughter with cancer who missed a year of formal education, but got through with the help of a tutor. Another respondent claimed the shadow tutoring workforce “props up” some “outstanding” schools – private, grammar and state.

Not everyone was positive about the impact of tuition. “It can cause students to not work in lessons,” said one teacher. Another said: “The need for tutoring frightens me. Schools should be able to offer students the support they need in class sizes that are manageable.” While one parent said: “I resent it when having a tutor is seen as a class crime,” another acknowledged the unfairness at the heart of the system: “I feel uncomfortable that we can afford to pay for this privilege.”

The callout also revealed the appeal of private tuition for teachers, whose salaries have been depressed for years while the demands upon them have grown. Some said they did private tutoring to boost their income; others, tired of the one-size-fits-all approach in schools, have quit their jobs to do it full time.

Asked about the boom in private tuition, the Department for Education responded that standards are rising in schools and that the attainment gap between rich and poor pupils is shrinking. “While we believe families shouldn’t have to pay for private tuition, it has always been part of the system and parents have freedom to do this,” a spokesman said.

“Tutoring is huge, it’s getting bigger and it’s not going away,” says the Sutton Trust’s Lampl. “You can’t stop people from doing it. What we’ve got to do is make it more accessible for parents who currently can’t afford it.”

Clayton, the retired garage worker from Bradford, is not a rich man, but he wants to invest what he has in his grandson’s future. His hopes for Brooklyn are modest and honourable and shared by parents and grandparents everywhere. “I want Brooklyn to have a good start in life … Nobody gave me a leg up. I’m trying to do something for him that I never got. I hope he ends up being a decent person when he grows up and gets a decent job and doesn’t have to struggle.”

Tuesday 4 December 2018

Opec: why Trump has Saudi Arabia over a barrel

David Sheppard and Ed Crooks in The FT

Reneé Earls has lived her whole life in west Texas, and watched oil booms come and go, but she has never seen anything like the buzz of activity in the industry today. “We are a hopping spot,” she says. “If you’re not working here, that’s because you’re not looking for a job, or you are unemployable . . . If you have a skill and want to work, you can name your price.”

Reneé Earls has lived her whole life in west Texas, and watched oil booms come and go, but she has never seen anything like the buzz of activity in the industry today. “We are a hopping spot,” she says. “If you’re not working here, that’s because you’re not looking for a job, or you are unemployable . . . If you have a skill and want to work, you can name your price.”

Ms Earls is chief executive of the chamber of commerce in Odessa, in the heart of the Permian basin, the shale formation stretching from west Texas into New Mexico that is the red-hot centre of the latest US oil boom. Production in the region rose by 1m barrels a day in the year to August, contributing to a record-breaking 2.1m b/d increase in US output that has made the country the world’s largest crude producer.

The shale boom has not only transformed once rundown towns deep in the west Texas desert; it is increasingly reshaping the landscape of international politics. The emergence of the US as a born-again energy superpower — one of the key factors in the recent fall in oil prices — has led politicians in Washington to weigh how it might reshape some of its oldest alliances, raising uncomfortable questions for the oil producers of the Middle East .

For Saudi Arabia, the US’s chief ally in the Arab world, the past two months have delivered a stark lesson in how its relationship with Washington has been redefined by the Texas oil revolution.

On Thursday and Friday ministers from Opec, the oil cartel that controls roughly a third of global production, and its allies including Russia and Kazakhstan, will meet in Vienna to decide how to respond to the 30 per cent plunge in oil prices to around $60 a barrel over the past two months. With US output surging, and Russia and Saudi Arabia also producing at close to record levels, traders are convinced the market will be awash with oil next year.

Previously such a fall would have prompted Opec and its allies to agree to cut production. But for Saudi Arabia, which remains the world’s top oil exporter and the cartel’s de facto leader, that decision has been complicated by the murder of Jamal Khashoggi.

The gruesome killing of the Saudi Arabian journalist and Washington Post columnist, a critic of the royal family, has revealed fissures in its prized relationship with the US.

US president Donald Trump has maintained his backing for Riyadh and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the country’s day-to-day ruler widely known as MBS, despite reports that the CIA has concluded that he ordered the operation against Khashoggi at the kingdom’s consulate in Istanbul. But his stance comes with conditions attached, one of which lies at the heart of the kingdom’s wellbeing: the oil price.

In statements, tweets and private communications Mr Trump has made clear his support for lower oil prices and his opposition to Riyadh moving to cut production, heaping pressure on a royal court shaken by the international backlash against the Khashoggi killing. The pressure from the White House has come despite Saudi Arabia raising production this summer to help make sure the market remained well supplied as the US reimposed sanctions on Iran. Riyadh’s position as Tehran’s chief rival in the region reflects a core part of the Trump administration’s foreign policy.

“The priority for Saudi Arabia is shoring up MBS’s position, and the key part of that is securing Trump’s backing,” says Derek Brower, a director of RS Energy Group. “Trump has clearly linked his support for MBS with several things . . . but it’s oil that seems to be at the top of his agenda.”

For the Trump administration, the calculation is straightforward. Lower oil prices mean cheaper petrol, providing a boost for consumers. The president has hailed the recent fall in prices as a “tax cut”, giving him some good news after a stock market wobble triggered by his confrontation with China over trade.

For Saudi Arabia, that creates a dilemma. Khalid al-Falih, its energy minister, has pushed ahead with plans to drum up support for cutting oil production by more than 1m b/d, but observers think he will be constrained by the need to appease Mr Trump.

Bob McNally, a consultant who has advised US administrations on oil policy, says Riyadh’s position is precarious. “If they orchestrate a high-profile Opec-plus cut that boosts Brent crude back up towards $70 they risk Trump’s wrath,” he says. “[But] if Riyadh bends entirely to Trump’s will and keeps production at record levels, an inventory glut will return and the bottom will fall out of crude prices.”

Ellen Wald, author of a history of Saudi Arabia’s oil industry, says the “ultimate success” for Riyadh from this week’s meeting would be “to quietly let people know that a cut is happening to raise the price, without drawing attention to the activity of Opec specifically.”

Yet history suggests that kind of mixed message risks pleasing no one — angering Mr Trump while not doing much to raise prices.

The stakes for Saudi Arabia are higher than just a single decision on output. Its alliance with the US has long been underpinned by oil supplies, with the resultant petrodollars recycled back into the American economy through the purchase of military hardware.

After a fall in prices in 2014, Riyadh renewed its attempts to diversify and modernise both its economy and wider society, aiming to reduce its dependence on oil revenues. But for the programme to have a chance of success, Saudi Arabia needs a higher oil price in the short term to help fund the changes.

The shale boom is eroding the foundations of one of the pillars of the alliance. US net oil imports, which peaked at about 13m b/d in 2005, have dropped to about 2.4m b/d this year. By the end of next year, they could be running at just 330,000 b/d, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

Saudi Arabia’s crude supplies remain crucial to the world economy, and to US consumer fuel prices. But Amy Myers Jaffe, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, says the US economy is much less vulnerable to a spike in prices than it was even a decade ago.

The evidence of the crude price fall four years ago and subsequent recovery is that the impact of changes on the American economy is now roughly neutral. “The US is not in the position it was in 2007-08, when we were facing a rising oil price that put strain on the current account deficit and the dollar,” she says. “That’s a big change.”

As politicians start to grasp the implications of that shift, it is strengthening the argument that the US no longer needs to shackle itself to Riyadh.

“The atmosphere in Washington has certainly changed following the killing of Jamal Khashoggi,” says Helima Croft, a former CIA analyst who now runs RBC Capital Markets’ natural resources analysis. “Politicians see the surge in US oil production and are wondering aloud whether the alliance is as necessary as it once was.”

Those questions are also starting to drive activity in Congress. Last week, the Senate voted 63-37 to advance a resolution demanding that the president end US armed forces’ activity “in or affecting Yemen”, where Saudi Arabia’s war against Iran-aligned Houthi rebels has exacerbated what aid groups describe as the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

Legislation that would allow the US to impose criminal penalties on members of Opec and their allies for acting as a cartel has also been making progress. For Saudi Arabia, which has extensive assets in the US including the largest refinery in North America, that legislation is a genuine threat.

Tim Kaine, the Democratic senator from Virginia who was a co-sponsor of the bipartisan legislation on Yemen, suggested the Khashoggi death had been the last straw for some. “It was really important for the Senate to send a message to Saudi Arabia: ‘you do not have a free pass’,” Mr Kaine told National Public Radio last week. “The president’s signal of complete impunity is not in accord with American values.”

In the autumn of 2014, the Saudi government tried to reassert its authority in the oil market against the nascent threat from shale. As a global glut of crude swelled up, Riyadh declined to cut production, in the belief it could drown the Texas producers in a sea of cheap oil.

But shale proved far more resilient than Saudi Arabia — the only country with significant spare production capacity — had hoped. Two years on Opec members returned to restricting output, with the help of Russia and other non-member producers, to lay the foundations for a recovery in prices.

As the oil price has fallen this autumn, the memories of that episode have been resurfacing. But Jason Bordoff of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy says there is at least one crucial difference. “We now know how resilient shale can be. We saw how companies could cut costs and become more efficient to keep producing. That complicates Opec’s decision-making,” he says. “This time around, Opec knows it can’t kill shale, but maybe just wound it.”

Ms Earls says the people of Odessa have been watching as oil prices have plunged in the past two months. Fundamentally, though, they “still feel very confident”, she adds, because of the producers’ long-term commitment. The Permian Strategic Partnership, an industry-backed group that works with communities to help develop badly-needed infrastructure including roads, houses and schools, estimates a further 60,000 jobs will be createdby 2025, a huge increase for an area that had a population of about 330,000 last year.

The rate at which new wells are brought into production in the Permian was already expected to slow, in part because of a shortage of pipeline capacity. If the fall in prices is sustained, it could mean the industry slows further across the US, raising questions too for the White House.

The gains to consumers from lower fuel prices will be offset by the hit to investment. The oil-dependent economies of Texas and North Dakota would bear the brunt of the hit, but it would also extend to other industries such as steelmaking, which has benefited from the boom in pipeline construction.

Bernadette Johnson, vice-president of market intelligence at Drillinginfo, a research group, says there are several oil producing regions, such as the Denver-Julesburg Basin of Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska, where a fall in US crude from $60 to $50 would make a significant difference to the economics.

“The companies think that it may just be a temporary thing, and that prices will rebound,” she says. “If the oil price stays where it is, we will see companies start to react.”

Yet while there may be a temporary slowdown, there is a general confidence in the US industry that its growth can continue. US officials say they are not concerned about the impact of lower oil prices, arguing that the industry will be able to continue to grow thanks to technological improvements and efficiency gains. Others are more sceptical, noting that US production contracted in 2016 when prices were at their nadir.

Will Giraud, executive vice-president of Concho Resources, one of the leading producers in the Permian Basin — where production is approaching 3.7m b/d — told investors last month: “I think there are several more years of very high growth, and it’s likely that the Permian gets into the 5m-6m or maybe even 7m b/d of production and then sustains that for a decent period.”

In the face of rampant US shale output, Saudi Arabia looks like it may still decide that angering Mr Trump is a price worth paying for a production cut that props up the oil price, whatever the heightened risks from the Khashoggi affair. But regardless of what the Saudis decide, the flow of oil from places such as Odessa will keep quietly eroding one of the old certainties that underpinned their relationship with the US. As Mr Brower at RS Energy puts it: “The pressures that Saudi Arabia are under are already immense.”

Monday 3 December 2018

The Stark Evidence of Everyday Racial Bias in Britain

Poll commissioned to launch series on unconscious bias shows gulf in negative experiences by ethnicity

Robert Booth and Aamna Mohdin in The Guardian

Half of the respondents from a minority background said they believed people sometimes did not realise they were treating them differently because of their ethnicity, suggesting unconscious bias, as well as more explicit and deliberate racism, has a major influence on the way millions of people who were born in the UK or moved here are treated.

As well as demonstrating how much more likely ethnic minorities are to report negative experiences that did not feature an explicitly racist element, the poll found that one in eight had heard racist language directed at them in the month before they were surveyed.

It also found troubling levels of concern about bias in the workplace, with 57% of minorities saying they felt they had to work harder to succeed in Britain because of their ethnicity, and 40% saying they earned less or had worse employment prospects for the same reason.

The poll persistently found evidence that the gap in negative experiences was not confined to the past. For example, one in seven people from ethnic minorities said they had been treated as a potential shoplifter in the last month, against one in 25 white people.

The findings come a year after Theresa May published a race disparity audit that identified differences in living standards, housing, work, policing and health. The prime minister pledged to “confront these issues we have identified” but admitted: “We still have a way to go if we’re truly going to have a country that does work for everyone.”

In October the government said employers could be forced to reveal salary figures broken down by ethnicity, as they already do for gender, in a move that lawyers predicted could lead to a flood of employment tribunal cases. Black, Asian and minority ethnic unemployment stands at 6.3%, compared with 3.6% for white people.

Bangladeshi and Pakistani households had an average income of nearly £9,000 a year less than white British households between 2014 and 2016, and the gap between white and black Caribbean and black British families was £5,500.

One of the few positive findings was that just over half of those surveyed said they had either never experienced someone directing racist language at them, or had not done so for at least five years.

However, the results raise concerns over efforts to forge a multicultural British identity, with 41% saying someone had assumed they were not British at some point in the last year because of their ethnicity.

People from minorities are twice as likely as white people to have been mistaken for staff in a restaurant, bar or shop. One in five said they had felt the need to alter their voice and appearance in the last year because of their ethnicity.

The effects of bias are not the same for all ethnicities. Half of black and mixed-race people felt they had been unfairly overlooked for a promotion or job application, compared with 41% of people from Asian backgrounds. Black people were more likely to feel they had to work harder to succeed because of their ethnicity.

Muslims living in Britain – a large minority at around 2.8 million people – are more likely to have negative experiences than other religious groups. They are more likely than Christians, people with no religion and other smaller religions to be stopped by the police, left out of social functions at work or college and find that people seem not to want to sit next to them on public transport.

A government spokesperson said the prime minister was determined that people of different ethnicities were treated equally. The spokesperson said: “One year on from [the race disparity audit’s] launch, we are delivering on our commitment to explain or change ethnic disparities in all areas of society including a £90m programme to help tackle youth unemployment and a Race at Work charter to help create greater opportunities for ethnic minority employees at work. We have also launched a consultation on mandatory ethnicity pay reporting.”

Robert Booth and Aamna Mohdin in The Guardian

Half of black, Asian and minority ethnic respondents in the poll said they believed people sometimes did not realise they were treating them differently because of their ethnicity. Photograph: Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

The extent of racial bias faced by black, Asian and minority ethnic citizens in 21st-century Britain has been laid bare in an unprecedented study showing a gulf in how people of different ethnicities are treated in their daily lives.

A survey for the Guardian of 1,000 people from minority ethnic backgrounds found they were consistently more likely to have faced negative everyday experiences – all frequently associated with racism – than white people in a comparison poll.

The extent of racial bias faced by black, Asian and minority ethnic citizens in 21st-century Britain has been laid bare in an unprecedented study showing a gulf in how people of different ethnicities are treated in their daily lives.

A survey for the Guardian of 1,000 people from minority ethnic backgrounds found they were consistently more likely to have faced negative everyday experiences – all frequently associated with racism – than white people in a comparison poll.

The survey found that 43% of those from a minority ethnic background had been overlooked for a work promotion in a way that felt unfair in the last five years – more than twice the proportion of white people (18%) who reported the same experience.

The results show that ethnic minorities are three times as likely to have been thrown out of or denied entrance to a restaurant, bar or club in the last five years, and that more than two-thirds believe Britain has a problem with racism.

The ICM poll, commissioned to launch a week-long investigation into bias in Britain, focuses on everyday experiences of prejudice that could be a result of unconscious bias – quick decisions conditioned by our backgrounds, cultural environment and personal experiences.

It is believed to be the first major piece of UK public polling to focus on ethnic minorities’ experiences of unconscious bias, and comes amid wider concerns about a shortage of research capturing the views of minority groups.

The poll found comprehensive evidence to support concerns that unconscious bias has a negative effect on the lives of Britain’s 8.5 million people from minority backgrounds that is not revealed by typical data on racism. For example:

• 38% of people from ethnic minorities said they had been wrongly suspected of shoplifting in the last five years, compared with 14% of white people, with black people and women in particular more likely to be wrongly suspected.

• Minorities were more than twice as likely to have encountered abuse or rudeness from a stranger in the last week.

• 53% of people from a minority background believed they had been treated differently because of their hair, clothes or appearance, compared with 29% of white people.

The Runnymede Trust, a racial equality thinktank, described the findings as “stark” and said they illustrated “everyday micro-aggressions” that had profound effects on Britain’s social structure.

“Racism and discrimination for BAME people and minority faith groups isn’t restricted to one area of life,” said Zubaida Haque, the trust’s deputy director. “If you’re not welcome in a restaurant as a guest because of the colour of your skin, you’re unlikely to get a job in the restaurant for the same reason. Structural and institutional racism is difficult to identify or prove, but it has much more far-reaching effects on people’s life chances.”

David Lammy, the Labour MP for Tottenham, said the findings were upsetting. “Racial prejudice continues to weigh on the lives of black and ethnic minority people in the UK. While we all share the same hard-won rights, our lived experience and opportunity can vary,” he said.

Recalling being stopped and searched when he was 12, Lammy said: “Stereotyping is not just something that happens, stereotyping is something that is felt, and it feels like sheer terror, confusion and shame.”

The results show that ethnic minorities are three times as likely to have been thrown out of or denied entrance to a restaurant, bar or club in the last five years, and that more than two-thirds believe Britain has a problem with racism.

The ICM poll, commissioned to launch a week-long investigation into bias in Britain, focuses on everyday experiences of prejudice that could be a result of unconscious bias – quick decisions conditioned by our backgrounds, cultural environment and personal experiences.

It is believed to be the first major piece of UK public polling to focus on ethnic minorities’ experiences of unconscious bias, and comes amid wider concerns about a shortage of research capturing the views of minority groups.

The poll found comprehensive evidence to support concerns that unconscious bias has a negative effect on the lives of Britain’s 8.5 million people from minority backgrounds that is not revealed by typical data on racism. For example:

• 38% of people from ethnic minorities said they had been wrongly suspected of shoplifting in the last five years, compared with 14% of white people, with black people and women in particular more likely to be wrongly suspected.

• Minorities were more than twice as likely to have encountered abuse or rudeness from a stranger in the last week.

• 53% of people from a minority background believed they had been treated differently because of their hair, clothes or appearance, compared with 29% of white people.

The Runnymede Trust, a racial equality thinktank, described the findings as “stark” and said they illustrated “everyday micro-aggressions” that had profound effects on Britain’s social structure.

“Racism and discrimination for BAME people and minority faith groups isn’t restricted to one area of life,” said Zubaida Haque, the trust’s deputy director. “If you’re not welcome in a restaurant as a guest because of the colour of your skin, you’re unlikely to get a job in the restaurant for the same reason. Structural and institutional racism is difficult to identify or prove, but it has much more far-reaching effects on people’s life chances.”

David Lammy, the Labour MP for Tottenham, said the findings were upsetting. “Racial prejudice continues to weigh on the lives of black and ethnic minority people in the UK. While we all share the same hard-won rights, our lived experience and opportunity can vary,” he said.

Recalling being stopped and searched when he was 12, Lammy said: “Stereotyping is not just something that happens, stereotyping is something that is felt, and it feels like sheer terror, confusion and shame.”

Half of the respondents from a minority background said they believed people sometimes did not realise they were treating them differently because of their ethnicity, suggesting unconscious bias, as well as more explicit and deliberate racism, has a major influence on the way millions of people who were born in the UK or moved here are treated.

As well as demonstrating how much more likely ethnic minorities are to report negative experiences that did not feature an explicitly racist element, the poll found that one in eight had heard racist language directed at them in the month before they were surveyed.

It also found troubling levels of concern about bias in the workplace, with 57% of minorities saying they felt they had to work harder to succeed in Britain because of their ethnicity, and 40% saying they earned less or had worse employment prospects for the same reason.

The poll persistently found evidence that the gap in negative experiences was not confined to the past. For example, one in seven people from ethnic minorities said they had been treated as a potential shoplifter in the last month, against one in 25 white people.

The findings come a year after Theresa May published a race disparity audit that identified differences in living standards, housing, work, policing and health. The prime minister pledged to “confront these issues we have identified” but admitted: “We still have a way to go if we’re truly going to have a country that does work for everyone.”

In October the government said employers could be forced to reveal salary figures broken down by ethnicity, as they already do for gender, in a move that lawyers predicted could lead to a flood of employment tribunal cases. Black, Asian and minority ethnic unemployment stands at 6.3%, compared with 3.6% for white people.

Bangladeshi and Pakistani households had an average income of nearly £9,000 a year less than white British households between 2014 and 2016, and the gap between white and black Caribbean and black British families was £5,500.

One of the few positive findings was that just over half of those surveyed said they had either never experienced someone directing racist language at them, or had not done so for at least five years.

However, the results raise concerns over efforts to forge a multicultural British identity, with 41% saying someone had assumed they were not British at some point in the last year because of their ethnicity.

People from minorities are twice as likely as white people to have been mistaken for staff in a restaurant, bar or shop. One in five said they had felt the need to alter their voice and appearance in the last year because of their ethnicity.

The effects of bias are not the same for all ethnicities. Half of black and mixed-race people felt they had been unfairly overlooked for a promotion or job application, compared with 41% of people from Asian backgrounds. Black people were more likely to feel they had to work harder to succeed because of their ethnicity.

Muslims living in Britain – a large minority at around 2.8 million people – are more likely to have negative experiences than other religious groups. They are more likely than Christians, people with no religion and other smaller religions to be stopped by the police, left out of social functions at work or college and find that people seem not to want to sit next to them on public transport.

A government spokesperson said the prime minister was determined that people of different ethnicities were treated equally. The spokesperson said: “One year on from [the race disparity audit’s] launch, we are delivering on our commitment to explain or change ethnic disparities in all areas of society including a £90m programme to help tackle youth unemployment and a Race at Work charter to help create greater opportunities for ethnic minority employees at work. We have also launched a consultation on mandatory ethnicity pay reporting.”

Friday 30 November 2018

Brace yourself, Britain. Brexit is about to teach you what a crisis actually is

Seven decades of prosperity have lulled the UK into thinking we’re special – that disasters only happen to other people writes David Bennun in The Guardian

Britain is not Kenya. It is, in the ordinary run of things, much better protected against such convulsions than a country such as Kenya. But do away with the ordinary run of things, and any place in the world can suffer as Kenya did then. You don’t have to look too far back at European history to see it, nor do you have to look away from home. The British people I know who most swiftly grasped and vividly understood the implications of present events as they began to unfold are Northern Irish. There’s a reason for that.

Democratic institutions, the rule of law, civic infrastructure, a culture of local and national governance in which corruption, while ever present, is exceptional rather than institutional: these things, flawed as they may be and ever improvable as they are, take generations, even centuries to build. But once they topple, they can topple at terrifying speed and with terrifying effect. Britain has forgotten what that’s like.

All the talk about the “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down around you. In liberal democracies enthusiasm for a revolution usually comes from people who have known nothing but the safety and freedom of the “system” – which is to say the imperfect protective structure – that they abhor. Talk to anyone who has experienced the glories of such upheaval and they are generally not quite so keen on it.

To be, politically speaking, a grownup is something to be sneered at these days. It means you’re lacking in imagination, in boldness of vision, in belief in a better country or a better world. That’s a view held invariably by people who would, without grownups running things, have been lucky to survive long enough to articulate it. Similarly, a contempt for expertise is inevitably expressed by those who, without experts contributing to society as they do, would be lucky to have a voice to speak with, let alone a platform on which to use it. Expertise, like democracy, is far from infallible; each, however, is always preferable to the alternative.

When the grownups fail, as they periodically do, and badly, what you need is better grownups. Awful things have happened, and do happen, in this country, chiefly as a result of bad policy and worse enactment. We don’t need to have homelessness, dependency on food banks or deprived areas ruled by criminals and bullies. We can afford to act against these evils, but we let them happen all the same. That shames us. Hand the keys and the controls over to eternal teenagers – populists of either stripe – and what you’ll get is a situation where that choice is gone.

We’re not special. If, in a deluded fit of national self-harm that ever more resembles the drift into war in 1914, we allow ourselves to wreck the complicated machinery that underpins our everyday lives without us ever having to think much about it, nobody will be coming to rescue us. Cassandra, as Cassandras are always ready to remind you, was right.

Keeping calm in Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire: ‘The idea that we’re protected, we’re exceptional, is not articulated … but it’s there.’ Photograph: JOHN ROBERTSON

Most British people don’t have the first inkling of what a crisis is. They think it’s a political thing. “Government in crisis”, and so on. Whatever happens at the top, life will go on as ever. There will be food in the shops, medical supplies in the hospitals, water in the taps and order on the streets (as much as there usually is). Anyone who warns you otherwise is a catastrophist, a drama queen, a scaremonger, a Cassandra.

That’s what a seven-decade period of general peace and collective prosperity does for you. It makes you think it’s normal, rather than a hard-won, fragile rarity in history. It makes most people complacent, and turns a small but unfortunately influential number into the kind of adolescent romantics who think you can smash up everything in the house and stick two fingers up to Mummy and Daddy because, no matter what you do, they will always be there to make it right in the end. Mummy and Daddy won’t let anything too bad happen to us.

The idea that we’re protected, we’re exceptional, is not articulated or usually even conscious. But it’s there. That this is who we are. Disaster – mass, national disaster – happens to other people, in other places.

But there is no such rule. No such guarantee. Mummy and Daddy won’t always come to bail us out. And if you’ve ever lived in one of those other places, chances are you will have seen how quickly what you thought was an orderly society can disintegrate under pressure. If you’ve never known gunfire and mobs on the streets, or empty taps and empty shelves, or power that’s off more than it’s on, or morgues full of the victims of racial, political or tribal violence, you don’t have a clue how easily that can happen.

I experienced all these things when I was growing up in Kenya. Some were routine; the more severe, mercifully less so. Branded on my memory from an attempted coup d’état in 1982 is the sound of automatic rifle fire along the road; the crowds surging like waves; confusion and misinformation crackling from the radio; most of all, hearing the account of my late father, a doctor, of the aftermath of what I can best describe as a pogrom, unleashed by the breakdown of order, against the Asian people of Nairobi, his hospital full of the dead and grievously wounded people, many of them children no older than I was.

All the talk of “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down

Most British people don’t have the first inkling of what a crisis is. They think it’s a political thing. “Government in crisis”, and so on. Whatever happens at the top, life will go on as ever. There will be food in the shops, medical supplies in the hospitals, water in the taps and order on the streets (as much as there usually is). Anyone who warns you otherwise is a catastrophist, a drama queen, a scaremonger, a Cassandra.

That’s what a seven-decade period of general peace and collective prosperity does for you. It makes you think it’s normal, rather than a hard-won, fragile rarity in history. It makes most people complacent, and turns a small but unfortunately influential number into the kind of adolescent romantics who think you can smash up everything in the house and stick two fingers up to Mummy and Daddy because, no matter what you do, they will always be there to make it right in the end. Mummy and Daddy won’t let anything too bad happen to us.

The idea that we’re protected, we’re exceptional, is not articulated or usually even conscious. But it’s there. That this is who we are. Disaster – mass, national disaster – happens to other people, in other places.

But there is no such rule. No such guarantee. Mummy and Daddy won’t always come to bail us out. And if you’ve ever lived in one of those other places, chances are you will have seen how quickly what you thought was an orderly society can disintegrate under pressure. If you’ve never known gunfire and mobs on the streets, or empty taps and empty shelves, or power that’s off more than it’s on, or morgues full of the victims of racial, political or tribal violence, you don’t have a clue how easily that can happen.

I experienced all these things when I was growing up in Kenya. Some were routine; the more severe, mercifully less so. Branded on my memory from an attempted coup d’état in 1982 is the sound of automatic rifle fire along the road; the crowds surging like waves; confusion and misinformation crackling from the radio; most of all, hearing the account of my late father, a doctor, of the aftermath of what I can best describe as a pogrom, unleashed by the breakdown of order, against the Asian people of Nairobi, his hospital full of the dead and grievously wounded people, many of them children no older than I was.

All the talk of “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down

Britain is not Kenya. It is, in the ordinary run of things, much better protected against such convulsions than a country such as Kenya. But do away with the ordinary run of things, and any place in the world can suffer as Kenya did then. You don’t have to look too far back at European history to see it, nor do you have to look away from home. The British people I know who most swiftly grasped and vividly understood the implications of present events as they began to unfold are Northern Irish. There’s a reason for that.

Democratic institutions, the rule of law, civic infrastructure, a culture of local and national governance in which corruption, while ever present, is exceptional rather than institutional: these things, flawed as they may be and ever improvable as they are, take generations, even centuries to build. But once they topple, they can topple at terrifying speed and with terrifying effect. Britain has forgotten what that’s like.

All the talk about the “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down around you. In liberal democracies enthusiasm for a revolution usually comes from people who have known nothing but the safety and freedom of the “system” – which is to say the imperfect protective structure – that they abhor. Talk to anyone who has experienced the glories of such upheaval and they are generally not quite so keen on it.

To be, politically speaking, a grownup is something to be sneered at these days. It means you’re lacking in imagination, in boldness of vision, in belief in a better country or a better world. That’s a view held invariably by people who would, without grownups running things, have been lucky to survive long enough to articulate it. Similarly, a contempt for expertise is inevitably expressed by those who, without experts contributing to society as they do, would be lucky to have a voice to speak with, let alone a platform on which to use it. Expertise, like democracy, is far from infallible; each, however, is always preferable to the alternative.

When the grownups fail, as they periodically do, and badly, what you need is better grownups. Awful things have happened, and do happen, in this country, chiefly as a result of bad policy and worse enactment. We don’t need to have homelessness, dependency on food banks or deprived areas ruled by criminals and bullies. We can afford to act against these evils, but we let them happen all the same. That shames us. Hand the keys and the controls over to eternal teenagers – populists of either stripe – and what you’ll get is a situation where that choice is gone.

We’re not special. If, in a deluded fit of national self-harm that ever more resembles the drift into war in 1914, we allow ourselves to wreck the complicated machinery that underpins our everyday lives without us ever having to think much about it, nobody will be coming to rescue us. Cassandra, as Cassandras are always ready to remind you, was right.

Imran Khan - The first 100 days

Najam Sethi in The Friday Times

Prime Minister Imran Khan is being hauled over the coals for failing to match words with deeds in his first 100 days in office. Indeed, he has made a laughing stock of himself by justifying 19 controversial decisions and 35 U-Turns so far as tactical policy befitting “great leaders” like Hitler and Napoleon. Since he wittingly proposed the 100-day yardstick to measure his government’s performance, he has only himself to blame for this media onslaught.

The most urgent item on PM Imran Khan’s agenda is related to the crisis in the economy manifested by a yawning gap in the balance of payments, falling forex reserves and a plummeting rupee. As opposition leader, he had thundered endlessly against crawling to the IMF or foreign countries for financial bailouts. Instead, he had pinned his hopes on billions in donations from overseas Pakistanis and tens of billions from unearthing black money stashed abroad. The problem arose when, after assuming office, he persisted in his delusionary approach, and the situation went from bad to worse. When his finance minister, Asad Umar, dared to baulk, he was forced to eat his words. It was only when the army chief, General Qamar Bajwa, “launched” himself purposefully that Imran Khan reluctantly packed his achkan, dragged himself off to Saudi Arabia and China with bowl in hand, and Asad Umar sat down to engage the IMF, both making a bald-faced virtue out of necessity.

But even this belated dawning of “wisdom” has failed to yield the desired results. China is not even ready to reveal the nature of its help. The Saudis have made an insignificant deposit that doesn’t tally with the tall expectations of government. And the IMF delegation has returned to Washington without any commitment, leaving the PM and his FM wringing their hands in despair.

The second item related to the efficient and honest functioning of government. On that score, there is even more confusion and contradiction. Parliament cannot function properly without consensual committees to steer legal reforms and oversee public accounts. But the hounding of the opposition parties at the behest of the interior ministry and civil-military “agencies” directed by Imran Khan himself has log-jammed the core committees. Worse, the PM’s intent to run Punjab from Bani Gala via a weak chief minister in a sea of cunning contenders for power like the Punjab Governor and the Speaker of the Provincial Assembly, has deadlocked the bureaucracy and administration. The rapid postings and transfers of high and low officials at one power broker’s behest or another’s has led to lack of direction and motivation.

The third agenda item is foreign policy. Here, too, the government’s stumbling is embarrassing. When the need of the hour is to keep the American beast at bay so that it doesn’t waylay the IMF on its way to Pakistan or lean on the Saudis to put pressure on us, Imran Khan has tried to win cheap brownie points at home by counter-tweeting President Trump. On the Afghanistan front, the war of words and proxy terrorism continues unabated even as Islamabad vows to be part of the solution rather than the problem.

Now Pakistan’s reopening of the Kartarpur corridor to the Sikh shrine of Baba Guru Nanak is being billed as some sort of “peace breakthrough” in Indo-Pak relations. It is nothing of the sort. Like the IMF, China and Saudi Arabia “openings”, this initiative comes courtesy General Bajwa whose bear hug of Indian cricketer Navjot Singh Sidhu at Imran Khan’s oath taking ceremony in Islamabad put Indian PM Narendra Modi and Punjab state CM Amarinder Singh in a tight corner. Neither politician’s prospects are too bright in the forthcoming elections in Punjab state next year. Therefore, they have reluctantly yielded to the Pakistani proposal only to curry favour with tens of millions of devout Sikhs. It is a tactical and short term concession as the hard, anti-Pakistan statements from Amarinder Singh and the Indian FM Sushma Swaraj, coupled with PM Modi’s refusal to attend the SAARC summit for the third year running, prove. Indeed, even as the Kartarpur protocol was being signed, proxy terrorists were taking a toll at the Chinese Consulate in Karachi, SP Tahir Dawar’s murdered body was being handed over to the Pak authorities at the Afghan border, suicide bombers were striking in the lower Orakzai Agency and India’s brutal repression in Held Kashmir showed no sign of abating.

On the Pakistan side, too, General Bajwa’s initiative is tactical, aimed only at reducing current Indian hostility – in the form of armed conflict along the LoC and proxy terrorism across the country – that destabilizes Pakistan and makes Imran Khan’s job of focusing on government difficult. This is the same Miltablishment that winked at the Labaiq Ya Rasul Allah during Nawaz Sharif’s time and crushed it in Imran Khan’s, the same that kicked Nawaz out for wanting to promote peace with India and is propping up Imran now at Kartarpur.

The Miltablishment has put all its eggs in Imran Khan’s basket. It will take more than 100 days of incompetence to shake its faith in their chosen man.

------

Bombs or Bread?

Najam Sethi in The Friday Times 16 Nov 2018

As we all know, the civil-military relationship in Nawaz Sharif’s time was severely strained. Among the factors often cited are Mr Sharif’s dogged pursuit of ex-army chief, General Pervez Musharraf, for the treasonable coup of 1999; his rush to “befriend” the hawkish Indian PM, Narendra Modi, without clearing the tactics and strategy with the Miltablishment; the “misuse” of the Pakistan-based jihadis in the proxy war with India, that led to the altercation reported in “Dawnleaks”; and Mr Sharif’s refusal to give the Miltablishment a seat at the roundtable determining CPEC projects and contracts.

But in a recent TV interview, Ishaq Dar, the ex-PMLN Finance Minister, has made a startling admission. He alluded to the issue of increasing defense budgets as the most significant area of conflict between the PMLN government and the Miltablishment. It appears that the Miltablishment wanted “more” money for new weapons systems because of the rising security threat from India but the PMLN government was strapped for funds and declined to do the needful.

The “Defense Budget” remains a sore point with every elected civilian government. At one time, it hovered around 30% of all budgetary expenditures and became grist for critics’ mills. So the Musharraf government cunningly took out military pensions from the Defense Budget and clubbed them with government expenditures, thereby reducing its weight as a percentage of budget expenditures and making it more palatable. When Coalition Fund Support from the US kicked in during the war against terrorism in FATA, it was also toted up outside the ambit of the Defense Budget. It has now become normal practice to post an increase of approximately 10 percent every year over actual expenditures for defense in the preceding year whilst beefing up the defense spending in supplementary budgets during the rest of the year, in effect giving the military much more than a 10% increase. The low levels of budgetary revenue collection and consequent government expenditures have also made defense budgets look overly inflated in percentage terms, especially in relation to India.

The security concerns of the Pak military have increased manifold for three main reasons. First, the aggressive nature of the Modi regime with its constant threat of “strategic strikes” across the LoC and its support of proxy war against Pakistan from non-state actors based in Afghanistan. Second, the perennial threat from its Cold Start Doctrine, now baptized afresh as Pro-Active Operations. Third, India is shopping for advanced weapons systems, the foremost being its proposed purchase of the Russian S-400 Triumf long-range, anti-missile system for over US$5.5 billion which is viewed in Islamabad as a major new threat. Now India has commissioned its first indigenously built nuclear-powered submarine, INS Arihant, armed with a 750km range submarine launched missile fitted with a nuclear warhead. Both these acquisitions are going to compel Pakistan to seek expensive equivalent systems to redress the security imbalance.

In other words, the Pakistan military will want lots more money going forward. The problem is that Pakistan’s economy has been failing and increasingly unable to bear this burden. Therefore, the choice of “bombs or bread” is bound to echo ever more furiously in the corridors of power, leading to renewed strains in civil-military relations and political instability that will in turn hamstring economic development and further strain the budget. When will this vicious circle end to create space for poverty alleviation, education, health, human resource development, etc.?

By definition, a “national security state” like Pakistan with a “permanent” and powerful enemy on its border like India requires a high level of defense preparedness. This is testified by the four wars, countless border skirmishes, and reciprocal proxy-terrorisms between the two in the last 70 years. Ostensibly, the root cause is the unresolved dispute over Kashmir. But we need to ask and answer some pertinent questions here.

How have many countries resolved similar border and territorial disputes in modern times without resorting to wars and proxy-terrorism? Which of the two is the originator of the wars in the subcontinent, regardless of the political provocation by the other? Why has the nuclearisation of the subcontinent spurred the conventional arms race instead of freezing it as originally argued? Who is hurting the most from this arms race, not just in financial terms but also in the cost to representative democracy of an overbearing political-military industrial complex that has created violent non-state actors at home to retain its political hegemony? Why is such a national security state unable to fully exploit Pakistan’s strategic location at the crossroads of three civilisations and markets – South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle-East – instead of replacing the yoke of one declining super power by that of another rising one? Why do we subscribe to the notion of a permanent enemy instead of a permanent peace in the national interest?

The USSR put a man in space and built over 10,000 nuclear bombs but couldn’t put enough bread on its shelves to feed its people. The arms race destroyed it. There are lessons in this for Pakistan.

Prime Minister Imran Khan is being hauled over the coals for failing to match words with deeds in his first 100 days in office. Indeed, he has made a laughing stock of himself by justifying 19 controversial decisions and 35 U-Turns so far as tactical policy befitting “great leaders” like Hitler and Napoleon. Since he wittingly proposed the 100-day yardstick to measure his government’s performance, he has only himself to blame for this media onslaught.