“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Thursday 9 March 2017

Tuesday 7 March 2017

Has Big Data already captured the world?

George Monbiot in The Guardian

Has a digital coup begun? Is big data being used, in the US and the UK, to create personalised political advertising, to bypass our rational minds and alter the way we vote? The short answer is probably not. Or not yet.

A series of terrifying articles suggests that a company called Cambridge Analytica helped to swing both the US election and the EU referendum by mining data from Facebook and using it to predict people’s personalities, then tailoring advertising to their psychological profiles. These reports, originating with the Swiss publication Das Magazin (published in translation by Vice), were clearly written in good faith, but apparently with insufficient diligence. They relied heavily on claims made by Cambridge Analytica that now appear to have been exaggerated. I found the story convincing, until I read the deconstructions by Martin Robbins on Little Atoms, Kendall Taggart on Buzzfeed and Leonid Bershidsky on Bloomberg.

None of this is to suggest we should not be vigilant. The Cambridge Analytica story gives us a glimpse of a possible dystopian future, especially in the US, where data protection is weak. Online information already lends itself to manipulation and political abuse, and the age of big data has scarcely begun. In combination with advances in cognitive linguistics and neuroscience, this data could become a powerful tool for changing the electoral decisions we make.

Our capacity to resist manipulation is limited. Even the crudest forms of subliminal advertising swerve past our capacity for reason and make critical thinking impossible. The simplest language shifts can trip us up. For example, when Americans were asked whether the federal government was spending too little on “assistance to the poor”, 65% agreed. When they were asked whether it was spending too little on “welfare”, 25% agreed. What hope do we have of resisting carefully targeted digital messaging that uses trigger words to influence our judgment? Those who are charged with protecting the integrity of elections should be urgently developing a new generation of safeguards.

Already big money exercises illegitimate power over political systems, making a mockery of democracy: the battering ram of campaign finance, which gives billionaires and corporations a huge political advantage over ordinary citizens; the dark money network (a web of lobby groups, funded by billionaires, that disguise themselves as thinktanks); astroturf campaigning (employing people to masquerade as grassroots movements); and botswarming (creating fake online accounts to give the impression that large numbers of people support a political position). All these are current threats to political freedom. Election authorities such as the Electoral Commission in the UK have signally failed to control these abuses, or even, in most cases, to acknowledge them.

China shows how much worse this could become. There, according to a recent article in Scientific American, deep-learning algorithms enable the state to develop its “citizen score”. This uses people’s online activities to determine how loyal and compliant they are, and whether they should qualify for jobs, loans or entitlement to travel to other countries. Combine this level of monitoring with nudging technologies – tools designed subtly to change people’s opinions and responses – and you develop a system that tends towards complete control.

Already big money exercises illegitimate power over political systems, making a mockery of democracy

Participation tends to be deep but narrow. Tech-savvy young men are often over-represented, while most of those who are alienated by offline politics remain, so far, alienated by online politics. But these results could be greatly improved, especially by using blockchain technology (a method of recording data), text-mining with the help of natural language processing (that enables very large numbers of comments and ideas to be synthesised and analysed), and other innovations that could make electronic democracy more meaningful, more feasible and more secure.

Of course, there are hazards here. No political system, offline or online, is immune to hacking; all systems require safeguards that evolve to protect them from being captured by money and undemocratic power. The regulation of politics lags decades behind the tricks, scams and new technologies deployed by people seeking illegitimate power. This is part of the reason for the mass disillusionment with politics: the belief that outcomes are rigged, and the emergence of a virulent anti-politics that finds expression in extremism and demagoguery.

Either we own political technologies, or they will own us. The great potential of big data, big analysis and online forums will be used by us or against us. We must move fast to beat the billionaires.

Has a digital coup begun? Is big data being used, in the US and the UK, to create personalised political advertising, to bypass our rational minds and alter the way we vote? The short answer is probably not. Or not yet.

A series of terrifying articles suggests that a company called Cambridge Analytica helped to swing both the US election and the EU referendum by mining data from Facebook and using it to predict people’s personalities, then tailoring advertising to their psychological profiles. These reports, originating with the Swiss publication Das Magazin (published in translation by Vice), were clearly written in good faith, but apparently with insufficient diligence. They relied heavily on claims made by Cambridge Analytica that now appear to have been exaggerated. I found the story convincing, until I read the deconstructions by Martin Robbins on Little Atoms, Kendall Taggart on Buzzfeed and Leonid Bershidsky on Bloomberg.

None of this is to suggest we should not be vigilant. The Cambridge Analytica story gives us a glimpse of a possible dystopian future, especially in the US, where data protection is weak. Online information already lends itself to manipulation and political abuse, and the age of big data has scarcely begun. In combination with advances in cognitive linguistics and neuroscience, this data could become a powerful tool for changing the electoral decisions we make.

Our capacity to resist manipulation is limited. Even the crudest forms of subliminal advertising swerve past our capacity for reason and make critical thinking impossible. The simplest language shifts can trip us up. For example, when Americans were asked whether the federal government was spending too little on “assistance to the poor”, 65% agreed. When they were asked whether it was spending too little on “welfare”, 25% agreed. What hope do we have of resisting carefully targeted digital messaging that uses trigger words to influence our judgment? Those who are charged with protecting the integrity of elections should be urgently developing a new generation of safeguards.

Already big money exercises illegitimate power over political systems, making a mockery of democracy: the battering ram of campaign finance, which gives billionaires and corporations a huge political advantage over ordinary citizens; the dark money network (a web of lobby groups, funded by billionaires, that disguise themselves as thinktanks); astroturf campaigning (employing people to masquerade as grassroots movements); and botswarming (creating fake online accounts to give the impression that large numbers of people support a political position). All these are current threats to political freedom. Election authorities such as the Electoral Commission in the UK have signally failed to control these abuses, or even, in most cases, to acknowledge them.

China shows how much worse this could become. There, according to a recent article in Scientific American, deep-learning algorithms enable the state to develop its “citizen score”. This uses people’s online activities to determine how loyal and compliant they are, and whether they should qualify for jobs, loans or entitlement to travel to other countries. Combine this level of monitoring with nudging technologies – tools designed subtly to change people’s opinions and responses – and you develop a system that tends towards complete control.

Already big money exercises illegitimate power over political systems, making a mockery of democracy

That’s the bad news. But digital technologies could also be a powerful force for positive change. Political systems, particularly in the Anglophone nations, have scarcely changed since the fastest means of delivering information was the horse. They remain remote, centralised and paternalist. The great potential for participation and deeper democratic engagement is almost untapped. Because the rest of us have not been invited to occupy them, it is easy for billionaires to seize and enclose the political cyber-commons.

A recent report by the innovation foundation Nesta argues that there are no quick or cheap digital fixes. But, when they receive sufficient support from governments or political parties, new technologies can improve the quality of democratic decisions. They can use the wisdom of crowds to make politics more transparent, to propose ideas that don’t occur to professional politicians, and to spot flaws and loopholes in government bills.

Among the best uses of online technologies it documents are the LabHacker and eDemocracia programmes in Brazil, which allow people to make proposals to their representatives and work with them to improve bills and policies; Parlement et Citoyens in France, which plays a similar role; vTaiwan, which crowdsources new parliamentary bills; the Better Reykjavík programme, which allows people to suggest and rank ideas for improving the city, and has now been used by more than half the population; and the Pirate party, also in Iceland, whose policies are chosen by its members, in both digital and offline forums. In all these cases, digital technologies are used to improve representative democracy rather than to replace it.

A recent report by the innovation foundation Nesta argues that there are no quick or cheap digital fixes. But, when they receive sufficient support from governments or political parties, new technologies can improve the quality of democratic decisions. They can use the wisdom of crowds to make politics more transparent, to propose ideas that don’t occur to professional politicians, and to spot flaws and loopholes in government bills.

Among the best uses of online technologies it documents are the LabHacker and eDemocracia programmes in Brazil, which allow people to make proposals to their representatives and work with them to improve bills and policies; Parlement et Citoyens in France, which plays a similar role; vTaiwan, which crowdsources new parliamentary bills; the Better Reykjavík programme, which allows people to suggest and rank ideas for improving the city, and has now been used by more than half the population; and the Pirate party, also in Iceland, whose policies are chosen by its members, in both digital and offline forums. In all these cases, digital technologies are used to improve representative democracy rather than to replace it.

Participation tends to be deep but narrow. Tech-savvy young men are often over-represented, while most of those who are alienated by offline politics remain, so far, alienated by online politics. But these results could be greatly improved, especially by using blockchain technology (a method of recording data), text-mining with the help of natural language processing (that enables very large numbers of comments and ideas to be synthesised and analysed), and other innovations that could make electronic democracy more meaningful, more feasible and more secure.

Of course, there are hazards here. No political system, offline or online, is immune to hacking; all systems require safeguards that evolve to protect them from being captured by money and undemocratic power. The regulation of politics lags decades behind the tricks, scams and new technologies deployed by people seeking illegitimate power. This is part of the reason for the mass disillusionment with politics: the belief that outcomes are rigged, and the emergence of a virulent anti-politics that finds expression in extremism and demagoguery.

Either we own political technologies, or they will own us. The great potential of big data, big analysis and online forums will be used by us or against us. We must move fast to beat the billionaires.

Trump is right on Russia

Jawed Naqvi in The Dawn

IT is a strange anomaly. Whenever India or Pakistan, or both, go into the cobra pose, hissing invectives and threatening to decimate each other, including with nuclear weapons, the world cries foul.

When Nawaz Sharif visits Delhi or when Narendra Modi drops in uninvited at a Lahore wedding, Indian and Pakistani peaceniks applaud together with the worried world. Yet, when Donald Trump wants to improve his country’s troubled relations with Vladimir Putin he is pilloried for even making the suggestion.

Granted he is not gender sensitive, that he has wronged and abused women and his mindset is possibly racist, driven by acute Islamophobia. I would liken Russia in this equation to the baby in Trump’s dirty bathtub. The deep state that contrived lies to invade Iraq or exulted in the wrecking of Libya, in cahoots with the media, seems to be facing an existential crisis with Trump’s presidency over his plans to touch base with Putin.

One day Trump excelled himself in his collaring of the deep state, which includes all major parties and the media. He said something to the effect that his country’s image was not exactly squeaky clean when it came to shedding blood around the world. That was his response to a Fox TV question about Putin’s alleged bloodlust as seen in the military operations in Aleppo.

Is the current American president really worse than the marauders of Iraq and Libya?

Trump’s blunt criticism of his country’s savage moments has been at par with Reverend Jeremiah Wright, the priest who baptised Barack Obama’s children. When in a fit of rage over an Israeli assault on Palestinian camps he yelled ‘goddamn America’ Obama cut off ties with the African American priest.

Then suddenly it began to rain scams on Trump. So and so met the Russian ambassador. So and so made eye contact with him. Trump’s attorney general is said to have a racist background. That was forgiven or grudgingly gulped down. Instead his alleged dalliances with Russian diplomats and/or businessmen were picked up for censure.

A wider conspiracy was unleashed to torpedo the new president’s still unwavering plans to improve relations with Putin. BBC dug out dirt on the Russians, which they are good at. Russia was a British quarry, which became America’s bête noire.

Cut to the day when Prime Minister Theresa May sauntered into Washington and Ankara recently and the media said she was fixing business deals. They omitted the fact that both her destinations involved allies who seemed to have lost interest in the old British fear-mongering called Russophobia. Trump’s fascination with Putin was by now legendary and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan too had shown signs of becoming disenchanted with the British-assigned role of playing an anti-Moscow Sancho Panza.

If we think freely and without the Cold War blinkers, May couldn’t have signed a groundbreaking deal with anybody bilaterally until the fate of Brexit was decided, which could be some years away. Trump looks destined not to last that long.

For Erdogan to become a member of the Russian-Iranian backed peace talks on Syria was a huge somersault by a country that was regarded as a lynchpin to Nato’s Middle East policy. Turkey is no longer insisting on the Syrian president’s head as condition to discuss a future setup in Damascus. Erdogan’s unease with the Americans became more pronounced with the botched coup attempt, which he blamed on Turkish dissidents seated in the US.

It is nearly impossible to believe that May did not discuss her worry about Russia and Putin with Trump and Erdogan. Russia has been a British bugbear for centuries even if Napoleon preceded it and other Europeans in turning an obsession with Russia into an exhausting and costly military expedition.

Russophobia as we know it is a British innovation. It was left to Winston Churchill to give the Cold War a newer variant of an old pursuit. The new seeds were planted in Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech. Then James Bond took over while Alfred Hitchcock also embraced the diabolical imagery of the Russians. Until then, Hollywood had been in hot pursuit of Germans as America’s horns and canines ogres.

Much earlier, before Western democracies were swamped with the Churchillian exhortations against Russia, British governors general and viceroys in India took it upon themselves to deepen and sustain the fear mongering. Delhi’s imposing colonial monument — India Gate — is a testimony to this perpetually induced fear with the rulers of Moscow. All sides of the landmark sandstone monument are lined with thousands of names of Sikh and Muslim soldiers who were sacrificed in the suicidal Afghan wars. May must have seen how Britain’s self-defeating obsession with Russia had dissipated into the brick-batting in Washington D.C. between the Democrats and the Republicans.

Going by usually trustworthy accounts Donald Trump is an unpredictable person, which makes him a dangerous leader of an already error-prone military power. Nevertheless, Noam Chomsky must have shocked the Democrats by suggesting that in his view John Kennedy was the most dangerous of presidents. Trump is lampooned daily, which is as it should be, as an unqualified gatecrasher in the White House. The suggestion, however, implies that the world was somehow better off under George W. Bush and, more worryingly, under his Dr Strangelove-like colleagues — Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney. Is Trump really worse than the marauders of Iraq and Libya?

Shorn of any media support in the heart of the land of free speech, Vladimir Putin wrote a piece for the American audiences in The New York Times of Sept 11 2013.

“Relations between us have passed through different stages. We stood against each other during the Cold War. But we were also allies once, and defeated the Nazis together.” Trump believes the two countries should jointly fight a new menace, the militant Islamic State group. His detractors within the deep state somehow seem not to like the idea.

IT is a strange anomaly. Whenever India or Pakistan, or both, go into the cobra pose, hissing invectives and threatening to decimate each other, including with nuclear weapons, the world cries foul.

When Nawaz Sharif visits Delhi or when Narendra Modi drops in uninvited at a Lahore wedding, Indian and Pakistani peaceniks applaud together with the worried world. Yet, when Donald Trump wants to improve his country’s troubled relations with Vladimir Putin he is pilloried for even making the suggestion.

Granted he is not gender sensitive, that he has wronged and abused women and his mindset is possibly racist, driven by acute Islamophobia. I would liken Russia in this equation to the baby in Trump’s dirty bathtub. The deep state that contrived lies to invade Iraq or exulted in the wrecking of Libya, in cahoots with the media, seems to be facing an existential crisis with Trump’s presidency over his plans to touch base with Putin.

One day Trump excelled himself in his collaring of the deep state, which includes all major parties and the media. He said something to the effect that his country’s image was not exactly squeaky clean when it came to shedding blood around the world. That was his response to a Fox TV question about Putin’s alleged bloodlust as seen in the military operations in Aleppo.

Is the current American president really worse than the marauders of Iraq and Libya?

Trump’s blunt criticism of his country’s savage moments has been at par with Reverend Jeremiah Wright, the priest who baptised Barack Obama’s children. When in a fit of rage over an Israeli assault on Palestinian camps he yelled ‘goddamn America’ Obama cut off ties with the African American priest.

Then suddenly it began to rain scams on Trump. So and so met the Russian ambassador. So and so made eye contact with him. Trump’s attorney general is said to have a racist background. That was forgiven or grudgingly gulped down. Instead his alleged dalliances with Russian diplomats and/or businessmen were picked up for censure.

A wider conspiracy was unleashed to torpedo the new president’s still unwavering plans to improve relations with Putin. BBC dug out dirt on the Russians, which they are good at. Russia was a British quarry, which became America’s bête noire.

Cut to the day when Prime Minister Theresa May sauntered into Washington and Ankara recently and the media said she was fixing business deals. They omitted the fact that both her destinations involved allies who seemed to have lost interest in the old British fear-mongering called Russophobia. Trump’s fascination with Putin was by now legendary and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan too had shown signs of becoming disenchanted with the British-assigned role of playing an anti-Moscow Sancho Panza.

If we think freely and without the Cold War blinkers, May couldn’t have signed a groundbreaking deal with anybody bilaterally until the fate of Brexit was decided, which could be some years away. Trump looks destined not to last that long.

For Erdogan to become a member of the Russian-Iranian backed peace talks on Syria was a huge somersault by a country that was regarded as a lynchpin to Nato’s Middle East policy. Turkey is no longer insisting on the Syrian president’s head as condition to discuss a future setup in Damascus. Erdogan’s unease with the Americans became more pronounced with the botched coup attempt, which he blamed on Turkish dissidents seated in the US.

It is nearly impossible to believe that May did not discuss her worry about Russia and Putin with Trump and Erdogan. Russia has been a British bugbear for centuries even if Napoleon preceded it and other Europeans in turning an obsession with Russia into an exhausting and costly military expedition.

Russophobia as we know it is a British innovation. It was left to Winston Churchill to give the Cold War a newer variant of an old pursuit. The new seeds were planted in Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech. Then James Bond took over while Alfred Hitchcock also embraced the diabolical imagery of the Russians. Until then, Hollywood had been in hot pursuit of Germans as America’s horns and canines ogres.

Much earlier, before Western democracies were swamped with the Churchillian exhortations against Russia, British governors general and viceroys in India took it upon themselves to deepen and sustain the fear mongering. Delhi’s imposing colonial monument — India Gate — is a testimony to this perpetually induced fear with the rulers of Moscow. All sides of the landmark sandstone monument are lined with thousands of names of Sikh and Muslim soldiers who were sacrificed in the suicidal Afghan wars. May must have seen how Britain’s self-defeating obsession with Russia had dissipated into the brick-batting in Washington D.C. between the Democrats and the Republicans.

Going by usually trustworthy accounts Donald Trump is an unpredictable person, which makes him a dangerous leader of an already error-prone military power. Nevertheless, Noam Chomsky must have shocked the Democrats by suggesting that in his view John Kennedy was the most dangerous of presidents. Trump is lampooned daily, which is as it should be, as an unqualified gatecrasher in the White House. The suggestion, however, implies that the world was somehow better off under George W. Bush and, more worryingly, under his Dr Strangelove-like colleagues — Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney. Is Trump really worse than the marauders of Iraq and Libya?

Shorn of any media support in the heart of the land of free speech, Vladimir Putin wrote a piece for the American audiences in The New York Times of Sept 11 2013.

“Relations between us have passed through different stages. We stood against each other during the Cold War. But we were also allies once, and defeated the Nazis together.” Trump believes the two countries should jointly fight a new menace, the militant Islamic State group. His detractors within the deep state somehow seem not to like the idea.

Monday 6 March 2017

Utopian thinking: the easy way to eradicate poverty

Rutger Bregman in The Guardian

Why do poor people make so many bad decisions? It’s a harsh question, but look at the data: poor people borrow more, save less, smoke more, exercise less, drink more and eat less healthily. Why?

Margaret Thatcher once called poverty a “personality defect”. Though not many would go quite so far, the view that there’s something wrong with poor people is not exceptional. To be honest, it was how I thought for a long time. It was only a few years ago that I discovered that everything I thought I knew about poverty was wrong.

It all started when I accidently stumbled on a paper by a few American psychologists. They had travelled 8,000 miles, to India, to carry out an experiment with sugar cane farmers. These farmers collect about 60% of their annual income all at once, right after the harvest. This means they are relatively poor one part of the year and rich the other. The researchers asked the farmers to do an IQ test before and after the harvest. What they discovered blew my mind. The farmers scored much worse on the tests before the harvest. The effects of living in poverty, it turns out, correspond to losing 14 points of IQ. That’s comparable to losing a night’s sleep, or the effects of alcoholism.

A few months later I discussed the theory with Eldar Shafir, a professor of behavioural science and public policy at Princeton University and one of the authors of this study. The reason, put simply: it’s the context, stupid. People behave differently when they perceive a thing to be scarce. What that thing is doesn’t much matter; whether it’s time, money or food, it all contributes to a “scarcity mentality”. This narrows your focus to your immediate deficiency. The long-term perspective goes out of the window. Poor people aren’t making dumb decisions because they are dumb, but because they’re living in a context in which anyone would make dumb decisions.

‘Indian sugar cane farmers scored much worse on IQ tests before the harvest than after.’ Photograph: Ajay Verma/REUTERS

Suddenly the reason so many of our anti-poverty programmes don’t work becomes clear. Investments in education, for example, are often completely useless. A recent analysis of 201 studies on the effectiveness of money management training came to the conclusion that it makes almost no difference at all. Poor people might come out wiser, but it’s not enough. As Shafir said: “It’s like teaching someone to swim and then throwing them in a stormy sea.”

So what can be done? Modern economists have a few solutions. We could make the paperwork easier, or send people a text message to remind them of their bills. These “nudges” are hugely popular with modern politicians, because they cost next to nothing. They are a symbol of this era, in which we so often treat the symptoms but ignore the causes.

I asked Shafir: “Why keep tinkering around the edges rather than just handing out more resources?” “You mean just hand out more money? Sure, that would be great,” he said. “But given the evident limitations … the brand of leftwing politics you have in Amsterdam doesn’t even exist in the States.”

But is this really an old-fashioned, leftist idea? I remembered reading about an old plan, something that has been proposed by some of history’s leading thinkers. Thomas More hinted at it in Utopia, more than 500 years ago. And its proponents have spanned the spectrum from the left to the right, from the civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King to the economist Milton Friedman.

It’s an incredibly simple idea: universal basic income – a monthly allowance of enough to pay for your basic needs: food, shelter, education. And it’s completely unconditional: not a favour, but a right.

But could it really be that simple? In the three years that followed, I read all I could find about basic income. I researched dozens of experiments that have been conducted across the globe. And it didn’t take long before I stumbled upon the story of a town that had done it, had eradicated poverty – after which nearly everyone forgot about it.

‘Everybody in Dauphin was guaranteed a basic income ensuring that no one fell below the poverty line.’ Photograph: Barrett & MacKay/Getty Images/All Canada Photos

This story starts in Winnipeg, Canada. Imagine a warehouse attic where nearly 2,000 boxes lie gathering dust. They are filled with data – graphs, tables, interviews – about one of the most fascinating social experiments ever conducted. Evelyn Forget, an economics professor at the University of Manitoba, first heard about the records in 2009. Stepping into the attic, she could hardly believe her eyes. It was a treasure trove of information on basic income.

The experiment had started in Dauphin, a town north-west of Winnipeg, in 1974. Everybody was guaranteed a basic income ensuring that no one fell below the poverty line. And for four years, all went well. But then a conservative government was voted into power. The new Canadian cabinet saw little point in the expensive experiment. So when it became clear there was no money left for an analysis of the results, the researchers decided to pack their files away. In 2,000 boxes.

When Forget found them, 30 years later, no one knew what, if anything, the experiment had demonstrated. For three years she subjected the data to all manner of statistical analysis. And no matter what she tried, the results were the same every time. The experiment – the longest and best of its kind – had been a resounding success.

Forget discovered that the people in Dauphin had not only become richer, but also smarter and healthier. The school performance of children improved substantially. The hospitalisation rate decreased by as much as 8.5%. Domestic violence was also down, as were mental health complaints. And people didn’t quit their jobs – the only ones who worked a little less were new mothers and students, who stayed in school longer.

The great thing about money is that people can use it to buy things they need, instead of things experts think they need

So here’s what I’ve learned. When it comes to poverty, we should stop pretending to know better than poor people. The great thing about money is that people can use it to buy things they need instead of things self-appointed experts think they need. Imagine how many brilliant would-be entrepreneurs, scientists and writers are now withering away in scarcity. Imagine how much energy and talent we would unleash if we got rid of poverty once and for all.

While it won’t solve all the world’s ills – and ideas such as a rent cap and more social housing are necessary in places where housing is scarce – a basic income would work like venture capital for the people. We can’t afford not to do it – poverty is hugely expensive. The costs of child poverty in the US are estimated at $500bn (£410bn) each year, in terms of higher healthcare spending, less education and more crime. It’s an incredible waste of potential. It would cost just $175bn, a quarter of the country’s current military budget, to do what Dauphin did long ago: eradicate poverty.

That should be our goal. The time for small thoughts and little nudges is past. The time has come for new, radical ideas. If this sounds utopian to you, then remember that every milestone of civilisation – the end of slavery, democracy, equal rights for men and women – was once a utopian fantasy too.

We’ve got the research, we’ve got the evidence, and we’ve got the means. Now, 500 years after Thomas More first wrote about basic income, we need to update our worldview. Poverty is not a lack of character. Poverty is a lack of cash.

Why do poor people make so many bad decisions? It’s a harsh question, but look at the data: poor people borrow more, save less, smoke more, exercise less, drink more and eat less healthily. Why?

Margaret Thatcher once called poverty a “personality defect”. Though not many would go quite so far, the view that there’s something wrong with poor people is not exceptional. To be honest, it was how I thought for a long time. It was only a few years ago that I discovered that everything I thought I knew about poverty was wrong.

It all started when I accidently stumbled on a paper by a few American psychologists. They had travelled 8,000 miles, to India, to carry out an experiment with sugar cane farmers. These farmers collect about 60% of their annual income all at once, right after the harvest. This means they are relatively poor one part of the year and rich the other. The researchers asked the farmers to do an IQ test before and after the harvest. What they discovered blew my mind. The farmers scored much worse on the tests before the harvest. The effects of living in poverty, it turns out, correspond to losing 14 points of IQ. That’s comparable to losing a night’s sleep, or the effects of alcoholism.

A few months later I discussed the theory with Eldar Shafir, a professor of behavioural science and public policy at Princeton University and one of the authors of this study. The reason, put simply: it’s the context, stupid. People behave differently when they perceive a thing to be scarce. What that thing is doesn’t much matter; whether it’s time, money or food, it all contributes to a “scarcity mentality”. This narrows your focus to your immediate deficiency. The long-term perspective goes out of the window. Poor people aren’t making dumb decisions because they are dumb, but because they’re living in a context in which anyone would make dumb decisions.

‘Indian sugar cane farmers scored much worse on IQ tests before the harvest than after.’ Photograph: Ajay Verma/REUTERS

Suddenly the reason so many of our anti-poverty programmes don’t work becomes clear. Investments in education, for example, are often completely useless. A recent analysis of 201 studies on the effectiveness of money management training came to the conclusion that it makes almost no difference at all. Poor people might come out wiser, but it’s not enough. As Shafir said: “It’s like teaching someone to swim and then throwing them in a stormy sea.”

So what can be done? Modern economists have a few solutions. We could make the paperwork easier, or send people a text message to remind them of their bills. These “nudges” are hugely popular with modern politicians, because they cost next to nothing. They are a symbol of this era, in which we so often treat the symptoms but ignore the causes.

I asked Shafir: “Why keep tinkering around the edges rather than just handing out more resources?” “You mean just hand out more money? Sure, that would be great,” he said. “But given the evident limitations … the brand of leftwing politics you have in Amsterdam doesn’t even exist in the States.”

But is this really an old-fashioned, leftist idea? I remembered reading about an old plan, something that has been proposed by some of history’s leading thinkers. Thomas More hinted at it in Utopia, more than 500 years ago. And its proponents have spanned the spectrum from the left to the right, from the civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King to the economist Milton Friedman.

It’s an incredibly simple idea: universal basic income – a monthly allowance of enough to pay for your basic needs: food, shelter, education. And it’s completely unconditional: not a favour, but a right.

But could it really be that simple? In the three years that followed, I read all I could find about basic income. I researched dozens of experiments that have been conducted across the globe. And it didn’t take long before I stumbled upon the story of a town that had done it, had eradicated poverty – after which nearly everyone forgot about it.

‘Everybody in Dauphin was guaranteed a basic income ensuring that no one fell below the poverty line.’ Photograph: Barrett & MacKay/Getty Images/All Canada Photos

This story starts in Winnipeg, Canada. Imagine a warehouse attic where nearly 2,000 boxes lie gathering dust. They are filled with data – graphs, tables, interviews – about one of the most fascinating social experiments ever conducted. Evelyn Forget, an economics professor at the University of Manitoba, first heard about the records in 2009. Stepping into the attic, she could hardly believe her eyes. It was a treasure trove of information on basic income.

The experiment had started in Dauphin, a town north-west of Winnipeg, in 1974. Everybody was guaranteed a basic income ensuring that no one fell below the poverty line. And for four years, all went well. But then a conservative government was voted into power. The new Canadian cabinet saw little point in the expensive experiment. So when it became clear there was no money left for an analysis of the results, the researchers decided to pack their files away. In 2,000 boxes.

When Forget found them, 30 years later, no one knew what, if anything, the experiment had demonstrated. For three years she subjected the data to all manner of statistical analysis. And no matter what she tried, the results were the same every time. The experiment – the longest and best of its kind – had been a resounding success.

Forget discovered that the people in Dauphin had not only become richer, but also smarter and healthier. The school performance of children improved substantially. The hospitalisation rate decreased by as much as 8.5%. Domestic violence was also down, as were mental health complaints. And people didn’t quit their jobs – the only ones who worked a little less were new mothers and students, who stayed in school longer.

The great thing about money is that people can use it to buy things they need, instead of things experts think they need

So here’s what I’ve learned. When it comes to poverty, we should stop pretending to know better than poor people. The great thing about money is that people can use it to buy things they need instead of things self-appointed experts think they need. Imagine how many brilliant would-be entrepreneurs, scientists and writers are now withering away in scarcity. Imagine how much energy and talent we would unleash if we got rid of poverty once and for all.

While it won’t solve all the world’s ills – and ideas such as a rent cap and more social housing are necessary in places where housing is scarce – a basic income would work like venture capital for the people. We can’t afford not to do it – poverty is hugely expensive. The costs of child poverty in the US are estimated at $500bn (£410bn) each year, in terms of higher healthcare spending, less education and more crime. It’s an incredible waste of potential. It would cost just $175bn, a quarter of the country’s current military budget, to do what Dauphin did long ago: eradicate poverty.

That should be our goal. The time for small thoughts and little nudges is past. The time has come for new, radical ideas. If this sounds utopian to you, then remember that every milestone of civilisation – the end of slavery, democracy, equal rights for men and women – was once a utopian fantasy too.

We’ve got the research, we’ve got the evidence, and we’ve got the means. Now, 500 years after Thomas More first wrote about basic income, we need to update our worldview. Poverty is not a lack of character. Poverty is a lack of cash.

Turn, flight and parabola separate a genuine spinner from an ordinary one

Nagraj Gollapudi in Cricinfo

Rajinder Goel, Padmakar Shivalkar and V V Kumar, three spinners who traumatised batsmen from the 1960s to the late-1980s, will be honoured by the BCCI on March 8 for their services to Indian cricket. Goel and Shivalkar, both left-arm spinners, will be given the CK Nayudu Lifetime Achievement Award. Kumar, a legspinner who played two Tests for India, will be given a special award for his "yeoman" service

In the following interview, the three talk about learning the basics of spin, their favourite practitioners of the art, and what has changed since their time.

What makes a good spinner?

Rajinder Goel - Hard work, practice, and some intellect on how to play the batsman - these are mandatory. Without practice you will not be able to master line and length, which are key to defeat the batsman.

Padmakar Shivalkar - Your basics of line and length need to be in place. The delivery needs to have a loop. This loop, which we used to call flight, needs to be a constant. Over the years, you increase this loop, adjust it. You lock the batsman first and then spread the web - he gets trapped steadily. But these things are not learned easily. It takes years and years of work before you reach the top level.

VV Kumar - There are many components involved. A spinner has to spend a lot of time in the nets. You can possibly become a spinner by participating in a practice session for a couple of hours. But you cannot become a real good spinner. A spinner must first understand what exactly is spinning the ball. A real spinner should possess the following qualities, otherwise he can only be termed a roller.

The number one thing is to have revolutions on the ball. Then you overspin your off- or legbreaks. There are two types when it comes to imparting spin: overspin and sidespin. A ball that is sidespun is mostly delivered with an improper action and is against the fundamentals of spin bowling. A real spinner will overspin his off- or legbreak, which, when it hits the ground, will have bounce, a lot of drift and turn. A sidespun delivery will only break - it will take a deviation. An overspun delivery will spin, bounce and then turn in or away sharply.

Then we come to control. The spinner needs to have control over the flight, the parabola. Flight does not mean just throwing the ball in the air. Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of breaking the ball to exhibit the parabola or dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back. But if the flight does not land properly, it can end up in a full toss.

The concept of a good spinner also includes bowling from over the wicket to both the right- and left-handed batsman. The present trend is for spinners to come round the wicket, which is negative and indicates you do not want to get punished. A spin bowler will have to give runs to get a wicket, but he should not gift it.

A spinner is not complete without mastering line and length. He must utilise the field to make the batsman play such strokes that will end up in a catch. That depends on the line he is bowling, his ability to flight the ball, to make the batsman come forward, or spin the ball to such an extent that the batsman probably tries to cut, pull, drive or edge. That is the culmination of a spinner planning and executing the downfall of a good batsman. For all this to happen, all the above fundamentals are compulsory. Turn, flight and parabola separate a genuine spinner from an ordinary spinner.

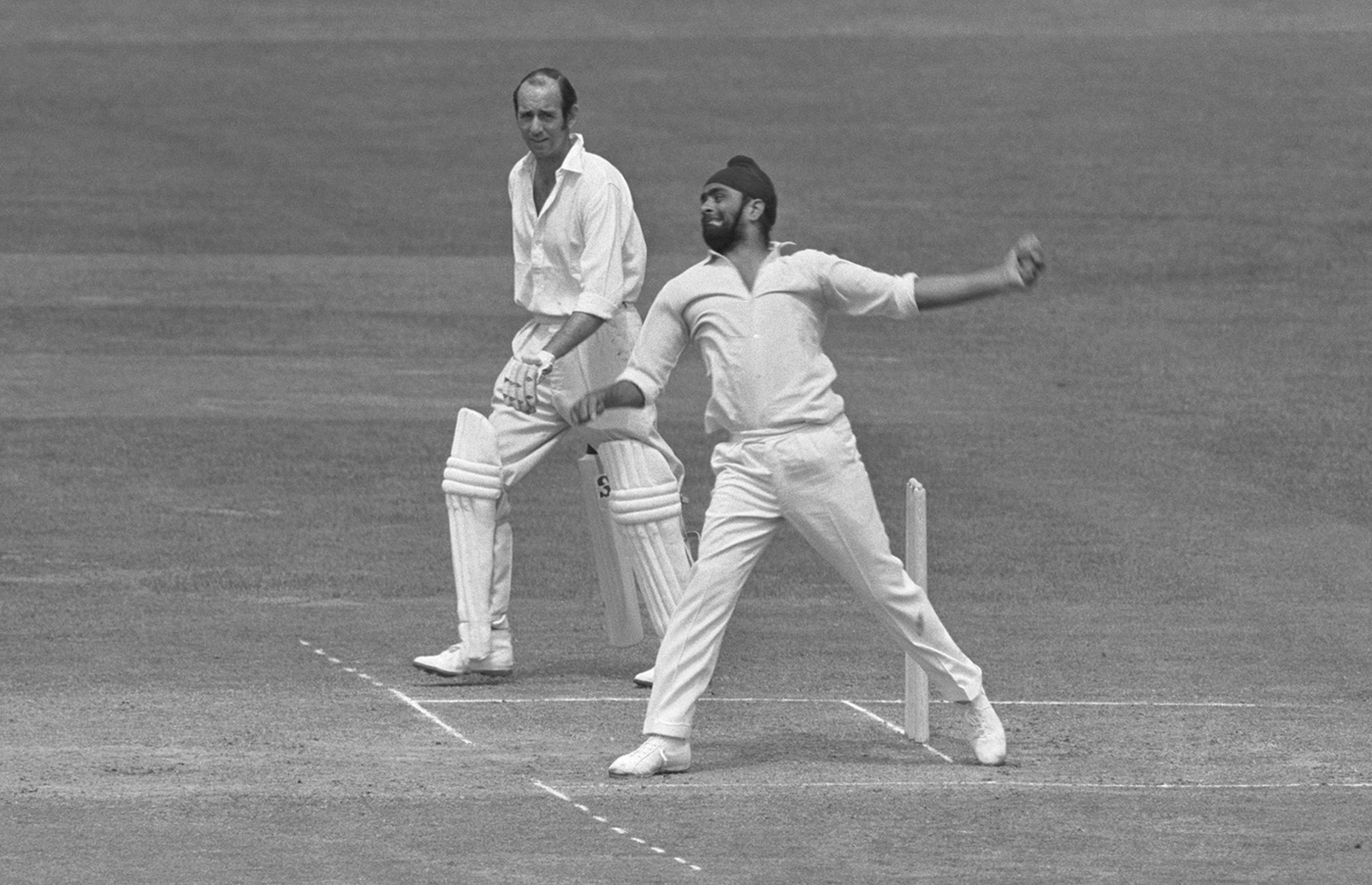

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty Images

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty Images

Did you have a mentor who helped you become a good spinner?

Goel - Lala Amarnath. It was 1957. I was in grade ten. I was part of the all-India schools camp in Chail in Himachal Pradesh. He taught me the basics of spin bowling. The most important thing he taught me was to come across the umpire and bowl from close to the stumps. He said with that kind of action I would be able to use the crease well and could play with the angles and the length easily.

Kumar - I am self-taught, and I say that without any arrogance. I started practising by spinning a golf ball against the wall. It would come back in a different direction. The ten-year-old in me got curious from that day about how that happened. I started reading good books by former players, like Eric Hollies, Clarrie Grimmett and Bill O' Reilly. Of course, my first book was The Art of Cricket by Don Bradman. That is how I equipped myself with the knowledge and put it in practice with a ball in hand.

Shivalkar - It was my whole team at Shivaji Park Gymkhana who made me what I became. If there was a bad ball, and there were many when I was a youngster in 1960-61, I learned a lot from what senior players said, their gestures, their body language. [Vijay] Manjrekar, [Manohar] Hardikar, [Chandrakant] Patankar would tell me: "Shivalkar, watch how he [the batsman] is playing. Tie him up." "Kay kartos? Changli bowling tak [What are you doing? Bowl well]," they would say, at times widening their eyes, at times raising their voice. I would obey that, but I would tell them I was trying to get the batsman out. You cannot always prevail over the batsman, but I cannot ever give up, I would tell myself.

What was your favourite mode of dismissal?

Goel - My strength was to attack the pads. I would maintain the leg-and-middle line. Batsmen who attempted to sweep or tried to play against the spin, I had a good chance of getting them caught in the close-in positions, or even get them bowled. I used to get bat-pad catches frequently, so I would call that my favourite.

"Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of the breaking the ball to exhibit the dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - My best way of getting a batsman out was to make him play forward and lure him to drive. Whether it was a quicker, flighted or flat delivery, I always tried to get the batsman on the front foot. Plenty of my wickets were caught at short leg, fine leg and short extra cover - that shows the batsman was going for the drives. I would not allow him to cut or pull. I would get these wickets through well-spun legbreaks, googlies, offspinners. You have to be very clear about your control and accuracy, otherwise you will be hit all over the place. You should always dominate the batsman. You have to play on his mind. Make him think it is a legbreak and instead he is beaten by flight and dip.

Shivalkar - I used to enjoy getting the batsman stumped. With my command over the loop, batsmen would step out of the crease and get trapped, beaten and stumped.

Tell us about one of your most prized wickets.

Goel - I was playing for State Bank of India against ACC (Associated Cement Companies) in the Moin-ud-Dowlah Gold Cup semi-finals in 1965 in Hyderabad. Polly saab [Polly Umrigar] was playing for ACC. He was a very good player of spin. He was playing well till our captain [Sharad] Diwadkar threw the second new ball to me. I got it to spin immediately and rapped Polly saab on the pads as he attempted to play me on the back foot. It was difficult to force a batsman like him to miss a ball, so it was a wicket I enjoyed taking.

Kumar - Let me talk about the wicket I did not get but one I cherish to this day. I was part of the South Zone team playing against the West Indians in January 1959 at Central College Ground in Bangalore. Garry Sobers came in to bat after I had got Conrad Hunte. I was thrilled and nervous to bowl to the best batsman. Gopi [CD Gopinath] told me to bowl as if I was bowling in any domestic match and not get bothered by the gifted fellow called Sobers.

The first ball was a legbreak, pitched outside off stump. Sobers moved across to pull me. Second ball was a topspinner, a full-length ball on the off stump. He went on the leg side and pushed it past point for four. The third ball was quickish, which he defended. Next, I delivered a googly on the middle stump. Garry came outside to drive, but the ball took the parabola and dipped. He checked his stroke and in the process sent me a simple, straightforward return catch. The ball jumped out of my hands. I put my hands on my head.

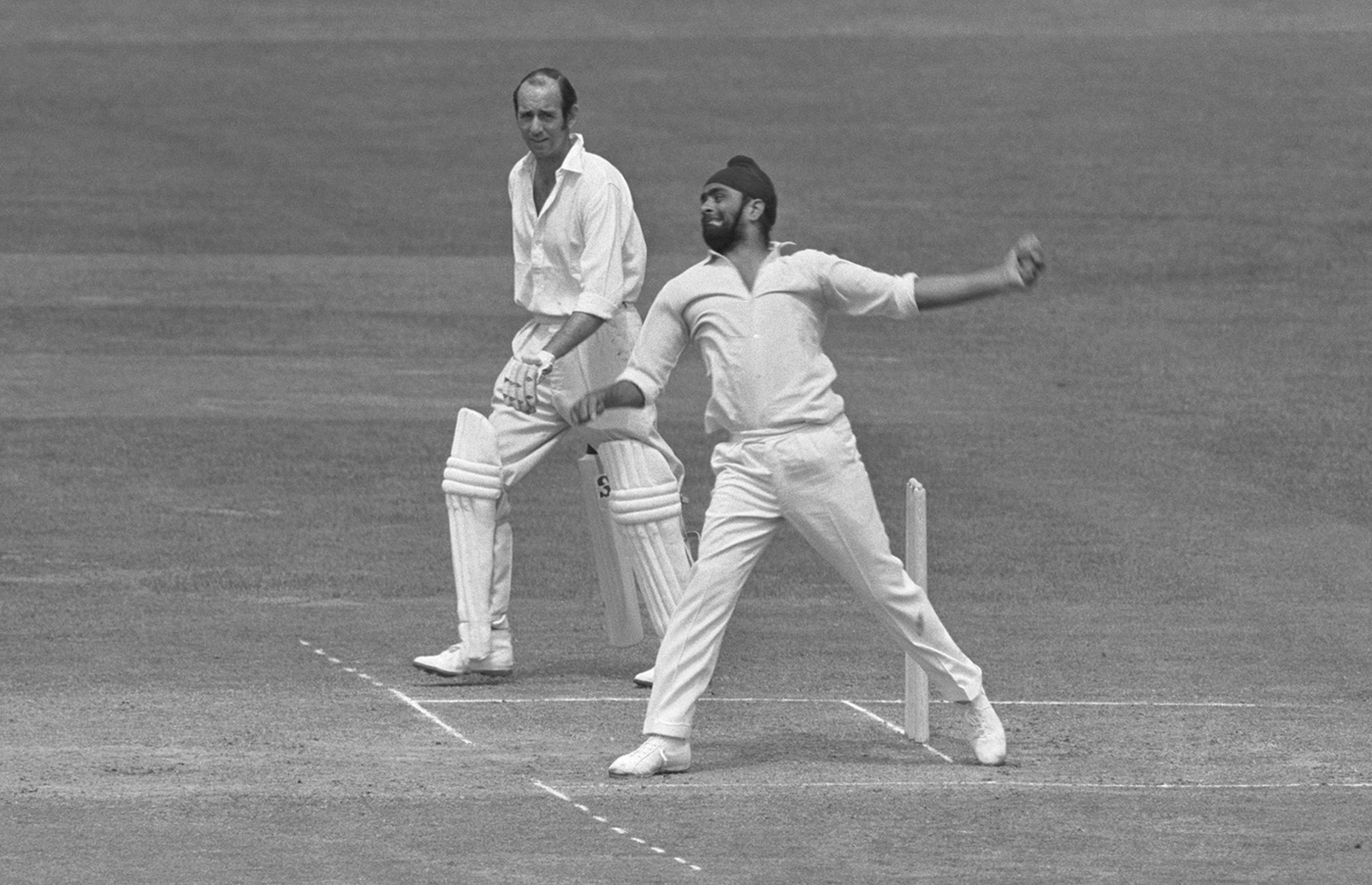

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA Photos

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA Photos

Who was the best spinner you saw bowl?

Goel - There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi. His high-arm action, the control he had over the ball, the way he would outguess a batsman - I loved Bedi's bowling. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches.

Kumar- I will call him my idol. I have not seen anybody else like Subhash Gupte, a brilliant legspinner. I have never seen anybody else reach his standards, including Shane Warne. Sobers himself said he was the best spinner he had ever played. In those days he operated on pitches that were absolutely dead tracks. It was Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him! That is why he is the greatest spinner I have seen.

Who was the best player of spin you bowled against?

Goel - Ramesh Saxena [Delhi and Bihar] and Vijay Bhosle [Bombay] were two good players of spin. Saxena would never allow the ball to spin. He would reach out to kill the spin. Bhosle was similar, and used to be aggressive against spin.

Kumar - Vijay Manjrekar was probably the best player of spin I encountered. What made him great was the time he had at his disposal to play the ball so late. And by doing that he made the spinner look mediocre.

"No one offers the loop anymore. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive"

PADMAKAR SHIVALKAR

Shivalkar - [Gundappa] Viswanath. He could change his shot at the last moment. Once, I remember I thought I had him. He was getting ready to cut me on the off stump, but the ball dipped and turned into him. I nearly said "Oooh", thinking he would be either lbw or bowled. But Vishy had amazing bat speed and he managed to get the bat down and the edge whisked past fine leg. He ran two and then looked at me and smiled. He had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrekar called him an artist. Vishy was a jaadugar [magician].

What has changed in spin bowling since the emergence of T20?

Goel - Earlier, we would flight the ball and not get bothered even if we got hit for four. We used to think of getting the batsman out. Now spinners think about arresting the runs. That is one big difference, which is an influence of T20.

Kumar - The three fundamentals I mentioned earlier do not exist in T20 cricket. Spinners are trying to bowl quick and waiting for the batsman to make the mistake. The spinner is not trying to make the batsman commit a mistake by sticking to the fundamentals. In four overs you cannot plan and execute.

Shivalkar - They have become defensive. No one offers the loop anymore. The difference has been brought upon by the bowlers themselves. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive. At times you should deliver from behind the popping crease, but you cannot allow the batsmen to guess that. That allows you more time for the delivery to land, for your flight to dip. The batsman is put in a fix. I have trapped batsmen that way.

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFP

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFP

We were playing for Tatas against Indian Oil [Corporation] in the Times Shield. Dilip Vengsarkar was standing at short extra cover. One batsman stepped out, trying to drive me, but Dilip took an easy catch. A couple of overs later he took another catch at the same spot. A third batsman departed in similar fashion in quick succession. Then a lower-order batsman played straight to Dilip, who dropped the catch as he was laughing at the ease with which I was getting the wickets. "Paddy, in my life I have never taken such easy catches," Dilip said, chuckling. The batsmen were not aware I was bowling from behind the crease. If they had noticed, they might have blocked it.

Rajinder Goel, Padmakar Shivalkar and V V Kumar, three spinners who traumatised batsmen from the 1960s to the late-1980s, will be honoured by the BCCI on March 8 for their services to Indian cricket. Goel and Shivalkar, both left-arm spinners, will be given the CK Nayudu Lifetime Achievement Award. Kumar, a legspinner who played two Tests for India, will be given a special award for his "yeoman" service

In the following interview, the three talk about learning the basics of spin, their favourite practitioners of the art, and what has changed since their time.

What makes a good spinner?

Rajinder Goel - Hard work, practice, and some intellect on how to play the batsman - these are mandatory. Without practice you will not be able to master line and length, which are key to defeat the batsman.

Padmakar Shivalkar - Your basics of line and length need to be in place. The delivery needs to have a loop. This loop, which we used to call flight, needs to be a constant. Over the years, you increase this loop, adjust it. You lock the batsman first and then spread the web - he gets trapped steadily. But these things are not learned easily. It takes years and years of work before you reach the top level.

VV Kumar - There are many components involved. A spinner has to spend a lot of time in the nets. You can possibly become a spinner by participating in a practice session for a couple of hours. But you cannot become a real good spinner. A spinner must first understand what exactly is spinning the ball. A real spinner should possess the following qualities, otherwise he can only be termed a roller.

The number one thing is to have revolutions on the ball. Then you overspin your off- or legbreaks. There are two types when it comes to imparting spin: overspin and sidespin. A ball that is sidespun is mostly delivered with an improper action and is against the fundamentals of spin bowling. A real spinner will overspin his off- or legbreak, which, when it hits the ground, will have bounce, a lot of drift and turn. A sidespun delivery will only break - it will take a deviation. An overspun delivery will spin, bounce and then turn in or away sharply.

Then we come to control. The spinner needs to have control over the flight, the parabola. Flight does not mean just throwing the ball in the air. Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of breaking the ball to exhibit the parabola or dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back. But if the flight does not land properly, it can end up in a full toss.

The concept of a good spinner also includes bowling from over the wicket to both the right- and left-handed batsman. The present trend is for spinners to come round the wicket, which is negative and indicates you do not want to get punished. A spin bowler will have to give runs to get a wicket, but he should not gift it.

A spinner is not complete without mastering line and length. He must utilise the field to make the batsman play such strokes that will end up in a catch. That depends on the line he is bowling, his ability to flight the ball, to make the batsman come forward, or spin the ball to such an extent that the batsman probably tries to cut, pull, drive or edge. That is the culmination of a spinner planning and executing the downfall of a good batsman. For all this to happen, all the above fundamentals are compulsory. Turn, flight and parabola separate a genuine spinner from an ordinary spinner.

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty Images

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty ImagesDid you have a mentor who helped you become a good spinner?

Goel - Lala Amarnath. It was 1957. I was in grade ten. I was part of the all-India schools camp in Chail in Himachal Pradesh. He taught me the basics of spin bowling. The most important thing he taught me was to come across the umpire and bowl from close to the stumps. He said with that kind of action I would be able to use the crease well and could play with the angles and the length easily.

Kumar - I am self-taught, and I say that without any arrogance. I started practising by spinning a golf ball against the wall. It would come back in a different direction. The ten-year-old in me got curious from that day about how that happened. I started reading good books by former players, like Eric Hollies, Clarrie Grimmett and Bill O' Reilly. Of course, my first book was The Art of Cricket by Don Bradman. That is how I equipped myself with the knowledge and put it in practice with a ball in hand.

Shivalkar - It was my whole team at Shivaji Park Gymkhana who made me what I became. If there was a bad ball, and there were many when I was a youngster in 1960-61, I learned a lot from what senior players said, their gestures, their body language. [Vijay] Manjrekar, [Manohar] Hardikar, [Chandrakant] Patankar would tell me: "Shivalkar, watch how he [the batsman] is playing. Tie him up." "Kay kartos? Changli bowling tak [What are you doing? Bowl well]," they would say, at times widening their eyes, at times raising their voice. I would obey that, but I would tell them I was trying to get the batsman out. You cannot always prevail over the batsman, but I cannot ever give up, I would tell myself.

What was your favourite mode of dismissal?

Goel - My strength was to attack the pads. I would maintain the leg-and-middle line. Batsmen who attempted to sweep or tried to play against the spin, I had a good chance of getting them caught in the close-in positions, or even get them bowled. I used to get bat-pad catches frequently, so I would call that my favourite.

"Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of the breaking the ball to exhibit the dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - My best way of getting a batsman out was to make him play forward and lure him to drive. Whether it was a quicker, flighted or flat delivery, I always tried to get the batsman on the front foot. Plenty of my wickets were caught at short leg, fine leg and short extra cover - that shows the batsman was going for the drives. I would not allow him to cut or pull. I would get these wickets through well-spun legbreaks, googlies, offspinners. You have to be very clear about your control and accuracy, otherwise you will be hit all over the place. You should always dominate the batsman. You have to play on his mind. Make him think it is a legbreak and instead he is beaten by flight and dip.

Shivalkar - I used to enjoy getting the batsman stumped. With my command over the loop, batsmen would step out of the crease and get trapped, beaten and stumped.

Tell us about one of your most prized wickets.

Goel - I was playing for State Bank of India against ACC (Associated Cement Companies) in the Moin-ud-Dowlah Gold Cup semi-finals in 1965 in Hyderabad. Polly saab [Polly Umrigar] was playing for ACC. He was a very good player of spin. He was playing well till our captain [Sharad] Diwadkar threw the second new ball to me. I got it to spin immediately and rapped Polly saab on the pads as he attempted to play me on the back foot. It was difficult to force a batsman like him to miss a ball, so it was a wicket I enjoyed taking.

Kumar - Let me talk about the wicket I did not get but one I cherish to this day. I was part of the South Zone team playing against the West Indians in January 1959 at Central College Ground in Bangalore. Garry Sobers came in to bat after I had got Conrad Hunte. I was thrilled and nervous to bowl to the best batsman. Gopi [CD Gopinath] told me to bowl as if I was bowling in any domestic match and not get bothered by the gifted fellow called Sobers.

The first ball was a legbreak, pitched outside off stump. Sobers moved across to pull me. Second ball was a topspinner, a full-length ball on the off stump. He went on the leg side and pushed it past point for four. The third ball was quickish, which he defended. Next, I delivered a googly on the middle stump. Garry came outside to drive, but the ball took the parabola and dipped. He checked his stroke and in the process sent me a simple, straightforward return catch. The ball jumped out of my hands. I put my hands on my head.

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA Photos

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA PhotosWho was the best spinner you saw bowl?

Goel - There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi. His high-arm action, the control he had over the ball, the way he would outguess a batsman - I loved Bedi's bowling. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches.

Kumar- I will call him my idol. I have not seen anybody else like Subhash Gupte, a brilliant legspinner. I have never seen anybody else reach his standards, including Shane Warne. Sobers himself said he was the best spinner he had ever played. In those days he operated on pitches that were absolutely dead tracks. It was Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him! That is why he is the greatest spinner I have seen.

Who was the best player of spin you bowled against?

Goel - Ramesh Saxena [Delhi and Bihar] and Vijay Bhosle [Bombay] were two good players of spin. Saxena would never allow the ball to spin. He would reach out to kill the spin. Bhosle was similar, and used to be aggressive against spin.

Kumar - Vijay Manjrekar was probably the best player of spin I encountered. What made him great was the time he had at his disposal to play the ball so late. And by doing that he made the spinner look mediocre.

"No one offers the loop anymore. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive"

PADMAKAR SHIVALKAR

Shivalkar - [Gundappa] Viswanath. He could change his shot at the last moment. Once, I remember I thought I had him. He was getting ready to cut me on the off stump, but the ball dipped and turned into him. I nearly said "Oooh", thinking he would be either lbw or bowled. But Vishy had amazing bat speed and he managed to get the bat down and the edge whisked past fine leg. He ran two and then looked at me and smiled. He had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrekar called him an artist. Vishy was a jaadugar [magician].

What has changed in spin bowling since the emergence of T20?

Goel - Earlier, we would flight the ball and not get bothered even if we got hit for four. We used to think of getting the batsman out. Now spinners think about arresting the runs. That is one big difference, which is an influence of T20.

Kumar - The three fundamentals I mentioned earlier do not exist in T20 cricket. Spinners are trying to bowl quick and waiting for the batsman to make the mistake. The spinner is not trying to make the batsman commit a mistake by sticking to the fundamentals. In four overs you cannot plan and execute.

Shivalkar - They have become defensive. No one offers the loop anymore. The difference has been brought upon by the bowlers themselves. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive. At times you should deliver from behind the popping crease, but you cannot allow the batsmen to guess that. That allows you more time for the delivery to land, for your flight to dip. The batsman is put in a fix. I have trapped batsmen that way.

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFP

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFPWe were playing for Tatas against Indian Oil [Corporation] in the Times Shield. Dilip Vengsarkar was standing at short extra cover. One batsman stepped out, trying to drive me, but Dilip took an easy catch. A couple of overs later he took another catch at the same spot. A third batsman departed in similar fashion in quick succession. Then a lower-order batsman played straight to Dilip, who dropped the catch as he was laughing at the ease with which I was getting the wickets. "Paddy, in my life I have never taken such easy catches," Dilip said, chuckling. The batsmen were not aware I was bowling from behind the crease. If they had noticed, they might have blocked it.

What is the one thing you cannot teach a spinner?

Goel- Practice. Line, length and control can only be gained through a lot of hard practice. No one can teach that. Spin bowling is a natural talent. Every ball you have to think as a spinner - what you bowl, how you try and counter the strength or weakness of a batsman, read his reactions, whether he plays flight well and then I need to increase my pace, and such things. All these subtle things only come through practice.

Kumar - There is no such thing that cannot be taught.

Shivalkar - This game is a play of andaaz [style]. That andaaz can only be learned with experience.

What are the things that every spinner needs to have in his toolkit?

Goel - Firstly, you have to check where the batsman plays well, so you don't pitch it in his area. Don't feed to his strengths. You have to guess this quickly.

"It was Subhash Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him!"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - A spinner should understand what line and length is before going into a match.

Shivalkar- You have to decide that on your own. What I have, what can I do are things only a spinner needs to understand on his own. For example, a batsman cuts me. Next time he tries, I push the ball in fast, getting him caught at the wicket or bowled.

Goel- Practice. Line, length and control can only be gained through a lot of hard practice. No one can teach that. Spin bowling is a natural talent. Every ball you have to think as a spinner - what you bowl, how you try and counter the strength or weakness of a batsman, read his reactions, whether he plays flight well and then I need to increase my pace, and such things. All these subtle things only come through practice.

Kumar - There is no such thing that cannot be taught.

Shivalkar - This game is a play of andaaz [style]. That andaaz can only be learned with experience.

What are the things that every spinner needs to have in his toolkit?

Goel - Firstly, you have to check where the batsman plays well, so you don't pitch it in his area. Don't feed to his strengths. You have to guess this quickly.

"It was Subhash Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him!"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - A spinner should understand what line and length is before going into a match.

Shivalkar- You have to decide that on your own. What I have, what can I do are things only a spinner needs to understand on his own. For example, a batsman cuts me. Next time he tries, I push the ball in fast, getting him caught at the wicket or bowled.

What is beautiful about spin bowling?

Goel - When the ball takes a lot of turn and then goes on to beat the bat - it is beautiful.

Kumar - A spinner has a lot of tools to befuddle the batsman with and be a nuisance to him at all times. He has plenty in his repertoire, which make him satisfying to watch as well as make spin bowling a spectacle.

Shivalkar - When you get your loop right, the best batsman gets trapped. You take satisfaction from the fact that the ball might have dipped, pitched, taken the turn, and then, probably, turned in or out to beat the batsman. You can then say "Wah". You have Vishy facing you. You assess what he is doing and accordingly set the trap.

Goel - When the ball takes a lot of turn and then goes on to beat the bat - it is beautiful.

Kumar - A spinner has a lot of tools to befuddle the batsman with and be a nuisance to him at all times. He has plenty in his repertoire, which make him satisfying to watch as well as make spin bowling a spectacle.

Shivalkar - When you get your loop right, the best batsman gets trapped. You take satisfaction from the fact that the ball might have dipped, pitched, taken the turn, and then, probably, turned in or out to beat the batsman. You can then say "Wah". You have Vishy facing you. You assess what he is doing and accordingly set the trap.

Sunday 5 March 2017

Thursday 2 March 2017

The struggle to be British: my life as a second-class citizen

Ismail Einashe in The Guardian

I used my British passport for the first time on a January morning in 2002, to board a Eurostar train to Paris. I was taking a paper on the French Revolution for my history A-level and was on a trip to explore the key sites of the period, including a visit to Louis XIV’s chateau at Versailles. When I arrived at Gare du Nord I felt a tingle of nerves cascade through my body: I had become a naturalised British citizen only the year before. As I got closer to border control my palms became sweaty, clutching my new passport. A voice inside told me the severe-looking French officers would not accept that I really was British and would not allow me to enter France. To my great surprise, they did.

Back then, becoming a British citizen was a dull bureaucratic procedure. When my family arrived as refugees from Somalia’s civil war, a few days after Christmas 1994, we were processed at the airport, and then largely forgotten. A few years after I got my passport all that changed. From 2004, adults who applied for British citizenship were required to attend a ceremony; to take an oath of allegiance to the monarch and make a pledge to the UK.

These ceremonies, organised by local authorities in town halls up and down the country, marked a shift in how the British state viewed citizenship. Before, it was a result of how long you had stayed in Britain – now it was supposed to be earned through active participation in society. In 2002, the government had also introduced a “life in the UK” test for prospective citizens. The tests point to something important: being a citizen on paper is not the same as truly belonging. Official Britain has been happy to celebrate symbols of multiculturalism – the curry house and the Notting Hill carnival – while ignoring the divisions between communities. Nor did the state give much of a helping hand to newcomers: there was little effort made to help families like mine learn English.

But in the last 15 years, citizenship, participation and “shared values” have been given ever more emphasis. They have also been accompanied by a deepening atmosphere of suspicion around people of Muslim background, particularly those who were born overseas or hold dual nationality. This is making people like me, who have struggled to become British, feel like second-class citizens.

When I arrived in Britain aged nine, I spoke no English and knew virtually nothing about this island. My family was moved into a run-down hostel on London’s Camden Road, which housed refugees – Kurds, Bosnians, Kosovans. Spending my first few months in Britain among other new arrivals was an interesting experience. Although, like my family, they were Muslim, their habits were different to ours. The Balkan refugees liked to drink vodka. After some months we had to move, this time to Colindale in north London.

Colindale was home to a large white working-class community, and our arrival was met with hostility. There were no warm welcomes from the locals, just a cold thud. None of my family spoke English, but I had soon mastered a few phrases in my new tongue: “Excuse me”, “How much is this?”, “Can I have …?”, “Thank you”. It was enough to allow us to navigate our way through the maze of shops in Grahame Park, the largest council estate in Barnet. This estate had opened in 1971, conceived as a garden city, but by the mid-1990s it had fallen into decay and isolation. This brick city became our home. As with other refugee communities before us, Britain had been generous in giving Somalis sanctuary, but was too indifferent to help us truly join in. Families like mine were plunged into unfamiliar cities, alienated and unable to make sense of our new homes. For us, there were no guidebooks on how to fit into British society or a map of how to become a citizen.

My family – the only black family on our street – stuck out like a sore thumb. Some neighbours would throw rubbish into our garden, perhaps because they disapproved of our presence. That first winter in Britain was brutal for us. We had never experienced anything like it and my lips cracked. But whenever it snowed I would run out to the street, stand in the cold, chest out and palms ready to meet the sky, and for the first time feel the sensation of snowflakes on my hands. The following summer I spent my days blasting Shaggy’s Boombastic on my cherished cassette player. But I also realised just how different I was from the children around me. Though most of them were polite, others called me names I did not understand. At the playground they would not let me join in their games – instead they would stare at me. I knew then, aged 11, that there was a distance between them and me, which even childhood curiosity could not overcome.

Although it was hard for me to fit in and make new friends, at least my English was improving. This was not the case for the rest of my family, so they held on to each other, afraid of what was outside our four walls. It was mundane growing up in working-class suburbia: we rarely left our street, except for occasional visits to the Indian cash-and-carry in Kingsbury to buy lamb, cumin and basmati rice. Sometimes one of our neighbours would swerve his van close to the pavement edge if it rained and he happened to spot my mother walking past, so he could splash her long dirac and hijab with dirty water. If he succeeded, he would lean out of the window, thumbs up, laughing hysterically. My mother’s response was always the same. She would walk back to the house, grab a towel and dry herself.

At secondary school in Edgware, the children were still mostly white, but there was a sizeable minority of Sikhs and Hindus. My new classmates would laugh at how I pronounced certain English words. I couldn’t say “congratulations” properly, the difficult part being the “gra”. I would perform saying that word, much to the amusement of my classmates. As the end of term approached, my classmates would ask where I was going on holiday. I would tell them, “Nowhere”, adding, “I don’t have a passport”.

When I was in my early teens, we were rehoused and I had to move to the south Camden Community school in Somers Town. There, a dozen languages were spoken and you could count the number of white students in my year on two hands. There was tension in the air and pupils were mostly segregated along ethnic lines – Turks, Bengalis, English, Somalis, Portuguese. Turf wars were not uncommon and fights broke out at the school gates. The British National party targeted the area in the mid-1990s, seeking to exploit the murder of a white teenager by a Bengali gang. At one point a halal butcher was firebombed.

Though I grew up minutes from the centre of Europe’s biggest city, I rarely ventured far beyond my own community. For us, there were no trips to museums, seaside excursions or cinema visits. MTV Base, the chicken shop and McDonald’s marked my teen years. I had little connection to other parts of Britain, beyond the snippets of middle-class life I observed via my white teachers. And I was still living with refugee documents, given “indefinite leave to remain” that could still be revoked at some future point. I realised then that no amount of identification with my new-found culture could make up for the reality that, without naturalisation, I was not considered British.

At 16, I took my GCSEs and got the grades to leave behind one of the worst state schools in London for one of the best: the mixed sixth form at Camden School for Girls. Most of the teens at my new school had previously attended some of Britain’s best private schools – City of London, Westminster, Highgate – and were in the majority white and middle-class.

It was strange to go from a Muslim-majority school to a sixth form where the children of London’s liberal set attended: only a mile apart, but worlds removed. I am not certain my family understood this change. My cousins thought it was weird that I did not attend the local college, but my old teachers insisted I go to the sixth form if I wanted to get into a good university. A few days after starting there, I got my naturalisation certificate, which opened the way for me to apply for my British passport.