David Madden in The Guardian

In a city where super-prime properties and tenant evictions are both on the rise, the housing system is broken and many residents are looking for someone to blame. For Londoners, rent consumes nearly two-thirds of the typical tenant’s income, and it will take 46 years for the average single person to save for a deposit on their first home. With overseas buyers acquiring as much as three-quarters of all new-build housing in London in recent years, it is understandable that foreigners would be cast as the villains behind the housing crisis. As a result, the London mayor Sadiq Khan last week launched an inquiry into foreign investment in the city’s housing market.

Londoners are not alone in questioning the impact of global investors in local housing markets. The issue is being politicised in cities throughout the world. In Vancouver, Canada, where single-family homes cost around 21 times the region’s median income, the city introduced a 15% tax on non-resident foreign property owners this August. Australian states that encompass Sydney, Melbourne, and other cities have also introduced or raised taxes on house purchases by foreigners.

It’s important to understand how overseas investment shapes residential opportunities and neighbourhood life. Khan is right to draw attention to the ways that housing in London is intertwined with global financial flows.

But foreign ownership is only part of a complex story – one that involves many actors and institutions located much closer to home. Searching for meddling non-natives to blame is ultimately a distraction. The idea that the housing crisis can be pinned on foreigners is a politically convenient simplification that risks letting other culprits off the hook, while doing little to change the status quo.

Focusing on overseas investors allows British policymakers to obscure their own role in producing the housing crisis. Over the decades, politicians at all levels of government have played an active part in creating this situation. Ministers promoted market-centric reforms such as the right to buy and more flexible tenancies, welcomed institutional investors into the housing market, and pushed through budget cuts in the name of austerity. These changes undermined council housing and weakened tenants’ security while making housing a more liquid commodity. Councillors across greater London have given the green light to estate demolition and gentrification, and allowed developers to build expensive new projects without significant numbers of affordable housing units.

Without these actions, we wouldn’t even be talking about Russian or Chinese investors. National and local political elites in Canada, Australia, the US, and elsewhere likewise bear responsibility for promoting the financialisation of housing.

Pointing at foreigners is a way to pretend to address the housing problem while ignoring the demands of activists

Blaming overseas investors similarly ignores domestic ones. Foreign owners may be particularly disconnected from local knowledge and conditions, but if they were simply replaced by their native counterparts who pursue the same strategies, the housing crisis would remain.

Pointing the finger at foreigners is also a way to pretend to address the housing problem while ignoring the demands of activists. The movements that have been mobilising in opposition to developers, councils and national government are fighting against displacement and in favour of establishing housing as a universal right. Whether exploitative landlords and serial collectors of luxury flats are British or foreign is beside the point. No housing activist has ever carried a sign demanding “British mansions for British oligarchs.”

None of this is to say that foreign ownership doesn’t matter. But the real issue is the political-economic condition that makes it possible: the commodification of housing. This term describes the process by which housing comes increasingly to function as a financial instrument rather than as shelter. Foreign ownership only matters because it is fuelling this broader process.

Rather than lashing out at foreigners, who are an easy target, city-dwellers and politicians such as Sadiq Khan need to ask tougher questions. Whose interests are served by urban regeneration in its current form? Why are collective resources such as public housing being dismantled and sold off? What alternatives to deepening housing inequalities are possible?

“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Tuesday 4 October 2016

Monday 3 October 2016

Sunday 2 October 2016

Nissan is an early sign of the downturns and the divisions Brexit could bring

Will Hutton in The Guardian

One of the few advantages of Brexit is that the unfolding debacle may be the trigger for the deep economic, political and constitutional reform that Britain so badly needs. It will only be by living through the searing events ahead that people will become convinced that the indulgent Eurosceptic untruths they have been fed are not only economically disastrous but open the way to forms of racism that most Britons, Leave voters included, instinctively find repellent. Brexit will force home some brutal realities.

Leave voters in Sunderland – 61% in favour – will have woken up on Friday to the news that Renault Nissan, the largest car plant in Europe and a crucial pillar of the local economy, employing 7,000 people, has deferred all new investment until the details of Brexit are clear. The chief executive, Carlos Ghosn, explained that it was not because the company did not value its Sunderland plant, its most efficient. Rather, as a major exporter to the EU, its profitability depends on the prevailing tariff regime, which promises to change sharply for the worse. “Important investment decisions,” he said, “would not be made in the dark.”

It is hard to fault Ghosn’s reasoning. Gaining control of EU immigration is both a matter of personal conviction and a political necessity for Theresa May. But how can that be squared with ongoing membership of the customs union that defines the single market and which requires acceptance of free movement? Concessions can only be minimal without wrecking the EU’s core structures. Moreover, the Tory hard Brexiters, wedded to the notion of a clean break from an EU they detest, are in the political ascendancy.

One senior official tells me that a hard Brexit is inevitable: the best that can be hoped for is perhaps some agreement on the movement of skilled people, but beyond that the future is trading on the terms organised by the World Trade Organisation.

If so, Renault Nissan will face up to 10% tariffs on the cars it ships to the EU. Unless the UK government is prepared to compensate it, a bill that could top £350m a year, it cannot make new investments. The Sunderland economy will be devastated. The same is true for the entire UK car industry. Last Wednesday,Jaguar Land Rover made similar remarks: if the position had been more explicit and fairly reported rather than airily dismissed as Project Fear, the wafer-thin 3,800 majority for Leave in Birmingham might have switched their vote.

Every part of our economy involved in selling into Europe will be affected both by the rise in tariffs and by the new necessity to guarantee that our products and services meet EU regulatory standards, the so-called passport. This doesn’t only apply to the City where 5,500 UK registered firms turn out to hold the invaluable passport, but to tens of thousand of companies across the economy.

The Brexiters insist the losses will be more than compensated for by the wave of trade deals now open to be signed, but trade deals take many years to negotiate. More crucially, there is no free-trade world out there; rather, there is a series of painstakingly constructed, reciprocal entries to markets, the biggest of which we are now abandoning. Liam Fox is delusional, as former business minister, Anna Soubry, declares, to pretend otherwise.

Nor do hard Brexiters confront the fact that alongside China and the US, Britain has accumulated a stunning $1tn-plus stock of foreign direct investment. Nearly 500 multinationals have regional or global headquarters here, more than twice the rest of Europe combined. They are here to take advantage of our ultra pro-business environment – so much for the Eurosceptic babble about being stifled by Brussels – and trade freely with the EU. Britain was becoming a combination of New York and California, with a whole continental hinterland in which to trade. Hard Brexit kills all that stone dead and puts phantoms in its place.

The years ahead will be ones of economic dislocation and stagnation. But the impact goes well beyond the economic. Hard Brexit legitimises anti-foreigner and anti-immigrant sentiment. When Britain’s flag outside the EU institutions is brought down and Messrs Farage, Davis, Johnson, Redwood, Fox et al delightedly hail the sovereignty and supremacy of Britishness, it could signal a new round of street-baiting of anybody who does not look and sound British: expect more attacks on Poles and Czechs from Essex to Yorkshire.

Politicians of right and left are fighting shy of delivering the condemnation this deserves. Rachel Reeves’s remarks at the Labour fringe, warning of a social explosion if immigration were not immediately curbed, show how far the permissible discourse on immigration and race has changed. Britain has moved over the past 50 years from being one of the most equal countries in Europe to the most unequal. The result is rising social tension, with immigration the tinder for enmity and hate. The hard-working immigrants who add so much vitality and energy to our society are blamed for ills that have deeper roots. Brexit has made this harder to say.

This conjunction of the economically and socially noxious horrifies not only me but also many Tories. Scotland’s Ruth Davidson, a bevy of ex-ministers, some in the cabinet and a large number of backbenchers are keenly aware of the slippery racist, culturally regressive and economically calamitous course their Brexiter colleagues are set on and are ready to fight for the soul of their party. George Osborne is positioning himself as their leader. It is an impending civil war, mirroring parallel feelings in the country at large.

Beyond that, the referendum raised profound constitutional questions. In other democracies, treaty and constitutional changes require at least 60% majorities in either the legislature or in a referendum. Britain’s unwritten constitution offers no such rules: a parliamentary majority confers monarchial power so a referendum can be called without any such framing. Article 50 is to be invoked without a parliamentary vote: a change of government in effect without a general election.

In good times, the constitution interests only obsessives. Suddenly, Britain’s constitutional vacuity is part of a deep national crisis. The economic and political structures, along with the biased media, that delivered this are rotten. The question is whether the will – and political coalitions – can be built to reform them. If not, Britain is sliding towards nasty, sectarian decline.

One of the few advantages of Brexit is that the unfolding debacle may be the trigger for the deep economic, political and constitutional reform that Britain so badly needs. It will only be by living through the searing events ahead that people will become convinced that the indulgent Eurosceptic untruths they have been fed are not only economically disastrous but open the way to forms of racism that most Britons, Leave voters included, instinctively find repellent. Brexit will force home some brutal realities.

Leave voters in Sunderland – 61% in favour – will have woken up on Friday to the news that Renault Nissan, the largest car plant in Europe and a crucial pillar of the local economy, employing 7,000 people, has deferred all new investment until the details of Brexit are clear. The chief executive, Carlos Ghosn, explained that it was not because the company did not value its Sunderland plant, its most efficient. Rather, as a major exporter to the EU, its profitability depends on the prevailing tariff regime, which promises to change sharply for the worse. “Important investment decisions,” he said, “would not be made in the dark.”

It is hard to fault Ghosn’s reasoning. Gaining control of EU immigration is both a matter of personal conviction and a political necessity for Theresa May. But how can that be squared with ongoing membership of the customs union that defines the single market and which requires acceptance of free movement? Concessions can only be minimal without wrecking the EU’s core structures. Moreover, the Tory hard Brexiters, wedded to the notion of a clean break from an EU they detest, are in the political ascendancy.

One senior official tells me that a hard Brexit is inevitable: the best that can be hoped for is perhaps some agreement on the movement of skilled people, but beyond that the future is trading on the terms organised by the World Trade Organisation.

If so, Renault Nissan will face up to 10% tariffs on the cars it ships to the EU. Unless the UK government is prepared to compensate it, a bill that could top £350m a year, it cannot make new investments. The Sunderland economy will be devastated. The same is true for the entire UK car industry. Last Wednesday,Jaguar Land Rover made similar remarks: if the position had been more explicit and fairly reported rather than airily dismissed as Project Fear, the wafer-thin 3,800 majority for Leave in Birmingham might have switched their vote.

Every part of our economy involved in selling into Europe will be affected both by the rise in tariffs and by the new necessity to guarantee that our products and services meet EU regulatory standards, the so-called passport. This doesn’t only apply to the City where 5,500 UK registered firms turn out to hold the invaluable passport, but to tens of thousand of companies across the economy.

The Brexiters insist the losses will be more than compensated for by the wave of trade deals now open to be signed, but trade deals take many years to negotiate. More crucially, there is no free-trade world out there; rather, there is a series of painstakingly constructed, reciprocal entries to markets, the biggest of which we are now abandoning. Liam Fox is delusional, as former business minister, Anna Soubry, declares, to pretend otherwise.

Nor do hard Brexiters confront the fact that alongside China and the US, Britain has accumulated a stunning $1tn-plus stock of foreign direct investment. Nearly 500 multinationals have regional or global headquarters here, more than twice the rest of Europe combined. They are here to take advantage of our ultra pro-business environment – so much for the Eurosceptic babble about being stifled by Brussels – and trade freely with the EU. Britain was becoming a combination of New York and California, with a whole continental hinterland in which to trade. Hard Brexit kills all that stone dead and puts phantoms in its place.

The years ahead will be ones of economic dislocation and stagnation. But the impact goes well beyond the economic. Hard Brexit legitimises anti-foreigner and anti-immigrant sentiment. When Britain’s flag outside the EU institutions is brought down and Messrs Farage, Davis, Johnson, Redwood, Fox et al delightedly hail the sovereignty and supremacy of Britishness, it could signal a new round of street-baiting of anybody who does not look and sound British: expect more attacks on Poles and Czechs from Essex to Yorkshire.

Politicians of right and left are fighting shy of delivering the condemnation this deserves. Rachel Reeves’s remarks at the Labour fringe, warning of a social explosion if immigration were not immediately curbed, show how far the permissible discourse on immigration and race has changed. Britain has moved over the past 50 years from being one of the most equal countries in Europe to the most unequal. The result is rising social tension, with immigration the tinder for enmity and hate. The hard-working immigrants who add so much vitality and energy to our society are blamed for ills that have deeper roots. Brexit has made this harder to say.

This conjunction of the economically and socially noxious horrifies not only me but also many Tories. Scotland’s Ruth Davidson, a bevy of ex-ministers, some in the cabinet and a large number of backbenchers are keenly aware of the slippery racist, culturally regressive and economically calamitous course their Brexiter colleagues are set on and are ready to fight for the soul of their party. George Osborne is positioning himself as their leader. It is an impending civil war, mirroring parallel feelings in the country at large.

Beyond that, the referendum raised profound constitutional questions. In other democracies, treaty and constitutional changes require at least 60% majorities in either the legislature or in a referendum. Britain’s unwritten constitution offers no such rules: a parliamentary majority confers monarchial power so a referendum can be called without any such framing. Article 50 is to be invoked without a parliamentary vote: a change of government in effect without a general election.

In good times, the constitution interests only obsessives. Suddenly, Britain’s constitutional vacuity is part of a deep national crisis. The economic and political structures, along with the biased media, that delivered this are rotten. The question is whether the will – and political coalitions – can be built to reform them. If not, Britain is sliding towards nasty, sectarian decline.

Trumper, Pujara and the art of dominating a spinner

It was a distinct pleasure to watch India bat in the first Test against New Zealand. It was good to see spin bowling played so well.

I especially enjoyed the play of Cheteshwar Pujara. I love the way he quickly gets back to either play a forcing shot through the covers or a pull to the midwicket boundary. Many batsmen limit themselves by "closing off" when they play the pull shot, but Pujara opens up, thrusting his left leg towards the square-leg umpire, and creates a wider arc in which to place the ball. He was well supported by M Vijay, a dangerous opponent because he handles the new ball competently and can extend his innings by playing spin bowling well. This pair and Virat Kohli give India a trifecta of batsmen who can dictate terms to opposition spinners.

As well as watching the Test on television, I was also in the process of reading Gideon Haigh's excellent new book, Stroke of Genius. It's about Victor Trumper's batting artistry captured in one photograph, titled "Jumping Out". In his playing days, Trumper extolled the virtue of footwork with this simple philosophy: "Spoil a bowler's length and you've got him."

This statement accords with the best use of the feet against a top-class legspinner that I've witnessed. Following VVS Laxman's magnificent 2000-01 series against Australia in general and Shane Warne in particular, I asked Warne how he thought he had bowled. "I didn't think I bowled badly," replied Warne. "You didn't," I answered. "When a batsman comes out three metres and drives you wide of mid-on and then when you go higher and shorter to tempt him with the next delivery, he's quickly onto the back foot and pulls through midwicket, that's not bad bowling."

In the words of Trumper, Laxman's nimble footwork, ensured "he'd got him [Warne]." It's this type of decisive footwork that allows a batsman to dictate the bowler's field placings. Both Pujara and Vijay did this exquisitely by employing the late cut and either the square cut or the forcing shot off the back foot. By playing both shots, they forced the fielding captain to place a man behind as well as just in front of point. When a captain has to expend two men patrolling a limited area, it leaves some inviting gaps elsewhere.

Good footwork is not only decisive, it's also physically demanding if you play a long innings. Pujara, like my former team-mate Doug Walters, the best player of offspin bowling I've seen, pushes back with intent. If Mitchell Santner had done something similar instead of just swivelling in the crease, his admirable rearguard action may have continued longer.

Too many batsmen are easily tempted into lazy footwork. They either prop forward one pace or just swivel on the back foot rather than advancing to attack the delivery or quickly retreating to allow more time to place the shot.

Some right-hand batsmen also limit themselves by moving outside off stump to thwart offspinners. This theory is flawed because it's based on survival rather than on developing a method that creates more scoring opportunities as opposed to than fewer.

As well as stifling scoring opportunities, this theory also opens batsmen up to being ambushed by smart bowlers like R Ashwin. He achieved such a dismissal when he cleverly out-thought Ish Sodhi to bowl him behind his pads.

The more proficient a spin bowler, the more attacking a batsman's thought process needs to be. This doesn't mean coming up with ways to belt him to or over the boundary but rather thinking of how to score regularly and frustrate the spinner. This is a demanding process both physically and mentally and isn't achieved by lazy or leaden footwork.

For some time India has been the leading light in producing batsmen who are devoid of gimmicks and rely on tried and tested methods to score at every opportunity. Whatever development methods India are employing for their young batsmen, the rest of the cricket world should start taking notice.

Saturday 1 October 2016

Saudi Arabia is the flagging horse of the Gulf – but Britain is still backing it as an answer to Brexit

Patrick Cockburn in The Independent

Why does the British Government devote so much time and effort to cultivating the rulers of Bahrain, a tiny state notorious for imprisoning and torturing its critics? It is doing so when a Bahraini court is about to sentence the country’s leading human rights advocate, Nabeel Rajab, who has been held in isolation in a filthy cell full of ants and cockroaches, to as much as 15 years in prison for sending tweets criticising torture in Bahrain and the Saudi bombardment of Yemen.

Yet it has just been announced that Prince Charles and Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, are to make an official visit to Bahrain in November with the purpose of improving relations with Britain. It is not as though Bahrain has been short of senior British visitors of late, with the International Trade Minister Liam Fox going there earlier in September to meet the Crown Prince, Prime Minister and commerce minister. And, if this was not enough, in the last few days the Foreign Office Minister of State for Europe, Sir Alan Duncan, found it necessary to pay a visit to Bahrain where he met King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa and the interior minister, Sheikh Rashid al-Khalifa, whose ministry is accused of being responsible for some of the worst human rights abuses on the island since the Arab Spring protests there were crushed in 2011 with the assistance of Saudi troops.

Quite why Sir Alan, who might be thought to have enough on his plate in dealing with his area of responsibility in Europe in the era of Brexit, should find it necessary to visit Bahrain remains something of mystery. Sayed Ahmed Alwadei, director of advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, asks: “Why is Alan Duncan in Bahrain? He has no reasonable business being there as Minister of State for Europe” But Sir Alan does have a long record of befriending the Gulf monarchies, informing a journalist in July that Saudi Arabia “is not a dictatorship”.

The flurry of high level visits to Bahrain comes as Rajab, the president of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, awaits sentencing on next week on three charges stemming from his use of social media. These relates to Rajab tweeting and retweeting about torture in Bahrain’s Jau prison and the humanitarian crisis caused by Saudi-led bombing in Yemen. After he published an essay entitled “Letter From a Bahrain Jail” in the The New York Times a month ago, he was charged with publishing “false news and statements and malicious rumours that undermines the prestige of the kingdom”.

This “prestige” has taken a battering since 2011 when pro-democracy protesters, largely belonging to the Shia majority on the island, were savagely repressed by the security forces. Ever since, the Sunni monarchy has done everything to secure and reinforce its power, not hesitating to inflame Sunni-Shia tensions by stripping the country’s most popular Shia cleric, Sheikh Isa Qassim, of his citizenship on the grounds that he was serving the interests of a foreign power.

Repression has escalated since May with the suspension of the main Shia opposition party, al-Wifaq, and an extension to the prison sentence of its leader, Sheikh Ali Salman. The al-Khalifa dynasty presumably calculates that US and British objections to this clampdown are purely for the record and can safely be disregarded. The former Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond claimed unblushingly earlier this year that Bahrain was “travelling in the right direction” when it came to human rights and political reform. Evidently, this masquerade of concern for the rights of the majority in Bahrain is now being discarded, as indicated by the plethora of visits.

There are reasons which have nothing to do with human rights motivating the British Government, such as the recent agreement to expand a British naval base on the island with the expansion being paid for by Bahrain. In its evidence to the Select Committee on Foreign Affairs, the Government said that UK naval facilities on the island give “the Royal Navy the ability to operate not only in the Gulf but well beyond in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and North West Indian Ocean”. Another expert witness claimed that for Britain “the kingdom is a substitute for an aircraft carrier permanently stationed in the Gulf”.

These dreams of restored naval might are probably unrealistic, though British politicians may be particularly susceptible to them at the moment, imagining that Britain can rebalance itself politically and economically post-Brexit by closer relations with old semi-dependent allies such as the Gulf monarchies. These rulers ultimately depend on US and British support to stay in power, however many arms they buy. Bahrain matters more than it looks because it is under strong Saudi influence and what pleases its al-Khalifa rulers pleases the House of Saud.

But in kowtowing so abjectly to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf kingdoms, Britain may be betting on a flagging horse at the wrong moment. Britain, France and – with increasing misgivings – the US have gone along since 2011 with the Gulf state policy of regime change in Libya and Syria. Saudi Arabia and Qatar, in combination with Turkey, have provided crucial support for the armed opposition to Bashar al-Assad. Foreign envoys seeking to end the Syrian war since 2011 were struck by British and French adherence to the Saudi position, even though it meant a continuance of the war which has destabilised the region and to a mass exodus of refugees heading for Western Europe.

Whatever the Saudis and Gulf monarchies thought they were doing in Syria, it has not worked. They have been sawing off the branch on which they are sitting by spreading chaos and directly or indirectly supporting the rise of al-Qaeda-type organisations like Isis and al-Nusra. Likewise in their rivalry with Iran and the Shia powers, the Sunni monarchies are on the back foot, having escalated a ferocious war in Yemen which they are failing to win.

In the past week Saudi Arabia has suffered two setbacks that are as serious as any of these others: on Wednesday the US Congress voted overwhelmingly to override a presidential veto enabling the families of 9/11 victims to sue Saudi Arabia. In terms of US public opinion, the Saudi rulers are at last paying a price for their role in spreading Sunni extremism and for the bombing of Yemen. The Saudi brand is becoming toxic in the US as politicians respond to a pervasive belief among voters that there is Saudi complicity in the spread of terrorism and war.

The second Saudi setback is different, but also leaves it weaker. At the Opec conference in Algiers, Saudi Arabia dropped its long-term policy of pumping as much oil as it could, and agreed to production cuts in order to raise the price of crude. A likely motivation was simple shortage of money. The prospects for the new agreement are cloudy but it appears that Iran has got most of what it wanted in returning to its pre-sanctions production level. It is too early to see Saudi Arabia and its Gulf counterparts as on an inevitable road to decline, but their strength is ebbing.

Why does the British Government devote so much time and effort to cultivating the rulers of Bahrain, a tiny state notorious for imprisoning and torturing its critics? It is doing so when a Bahraini court is about to sentence the country’s leading human rights advocate, Nabeel Rajab, who has been held in isolation in a filthy cell full of ants and cockroaches, to as much as 15 years in prison for sending tweets criticising torture in Bahrain and the Saudi bombardment of Yemen.

Yet it has just been announced that Prince Charles and Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, are to make an official visit to Bahrain in November with the purpose of improving relations with Britain. It is not as though Bahrain has been short of senior British visitors of late, with the International Trade Minister Liam Fox going there earlier in September to meet the Crown Prince, Prime Minister and commerce minister. And, if this was not enough, in the last few days the Foreign Office Minister of State for Europe, Sir Alan Duncan, found it necessary to pay a visit to Bahrain where he met King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa and the interior minister, Sheikh Rashid al-Khalifa, whose ministry is accused of being responsible for some of the worst human rights abuses on the island since the Arab Spring protests there were crushed in 2011 with the assistance of Saudi troops.

Quite why Sir Alan, who might be thought to have enough on his plate in dealing with his area of responsibility in Europe in the era of Brexit, should find it necessary to visit Bahrain remains something of mystery. Sayed Ahmed Alwadei, director of advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, asks: “Why is Alan Duncan in Bahrain? He has no reasonable business being there as Minister of State for Europe” But Sir Alan does have a long record of befriending the Gulf monarchies, informing a journalist in July that Saudi Arabia “is not a dictatorship”.

The flurry of high level visits to Bahrain comes as Rajab, the president of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, awaits sentencing on next week on three charges stemming from his use of social media. These relates to Rajab tweeting and retweeting about torture in Bahrain’s Jau prison and the humanitarian crisis caused by Saudi-led bombing in Yemen. After he published an essay entitled “Letter From a Bahrain Jail” in the The New York Times a month ago, he was charged with publishing “false news and statements and malicious rumours that undermines the prestige of the kingdom”.

This “prestige” has taken a battering since 2011 when pro-democracy protesters, largely belonging to the Shia majority on the island, were savagely repressed by the security forces. Ever since, the Sunni monarchy has done everything to secure and reinforce its power, not hesitating to inflame Sunni-Shia tensions by stripping the country’s most popular Shia cleric, Sheikh Isa Qassim, of his citizenship on the grounds that he was serving the interests of a foreign power.

Repression has escalated since May with the suspension of the main Shia opposition party, al-Wifaq, and an extension to the prison sentence of its leader, Sheikh Ali Salman. The al-Khalifa dynasty presumably calculates that US and British objections to this clampdown are purely for the record and can safely be disregarded. The former Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond claimed unblushingly earlier this year that Bahrain was “travelling in the right direction” when it came to human rights and political reform. Evidently, this masquerade of concern for the rights of the majority in Bahrain is now being discarded, as indicated by the plethora of visits.

There are reasons which have nothing to do with human rights motivating the British Government, such as the recent agreement to expand a British naval base on the island with the expansion being paid for by Bahrain. In its evidence to the Select Committee on Foreign Affairs, the Government said that UK naval facilities on the island give “the Royal Navy the ability to operate not only in the Gulf but well beyond in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and North West Indian Ocean”. Another expert witness claimed that for Britain “the kingdom is a substitute for an aircraft carrier permanently stationed in the Gulf”.

These dreams of restored naval might are probably unrealistic, though British politicians may be particularly susceptible to them at the moment, imagining that Britain can rebalance itself politically and economically post-Brexit by closer relations with old semi-dependent allies such as the Gulf monarchies. These rulers ultimately depend on US and British support to stay in power, however many arms they buy. Bahrain matters more than it looks because it is under strong Saudi influence and what pleases its al-Khalifa rulers pleases the House of Saud.

But in kowtowing so abjectly to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf kingdoms, Britain may be betting on a flagging horse at the wrong moment. Britain, France and – with increasing misgivings – the US have gone along since 2011 with the Gulf state policy of regime change in Libya and Syria. Saudi Arabia and Qatar, in combination with Turkey, have provided crucial support for the armed opposition to Bashar al-Assad. Foreign envoys seeking to end the Syrian war since 2011 were struck by British and French adherence to the Saudi position, even though it meant a continuance of the war which has destabilised the region and to a mass exodus of refugees heading for Western Europe.

Whatever the Saudis and Gulf monarchies thought they were doing in Syria, it has not worked. They have been sawing off the branch on which they are sitting by spreading chaos and directly or indirectly supporting the rise of al-Qaeda-type organisations like Isis and al-Nusra. Likewise in their rivalry with Iran and the Shia powers, the Sunni monarchies are on the back foot, having escalated a ferocious war in Yemen which they are failing to win.

In the past week Saudi Arabia has suffered two setbacks that are as serious as any of these others: on Wednesday the US Congress voted overwhelmingly to override a presidential veto enabling the families of 9/11 victims to sue Saudi Arabia. In terms of US public opinion, the Saudi rulers are at last paying a price for their role in spreading Sunni extremism and for the bombing of Yemen. The Saudi brand is becoming toxic in the US as politicians respond to a pervasive belief among voters that there is Saudi complicity in the spread of terrorism and war.

The second Saudi setback is different, but also leaves it weaker. At the Opec conference in Algiers, Saudi Arabia dropped its long-term policy of pumping as much oil as it could, and agreed to production cuts in order to raise the price of crude. A likely motivation was simple shortage of money. The prospects for the new agreement are cloudy but it appears that Iran has got most of what it wanted in returning to its pre-sanctions production level. It is too early to see Saudi Arabia and its Gulf counterparts as on an inevitable road to decline, but their strength is ebbing.

Is globalisation no longer a good thing?

John O'Sullivan in The Economist

THERE IS NOTHING dark, still less satanic, about the Revolution Mill in Greensboro, North Carolina. The tall yellow-brick chimney stack, with red bricks spelling “Revolution” down its length, was built a few years after the mill was established in 1900. It was a booming time for local enterprise. America’s cotton industry was moving south from New England to take advantage of lower wages. The number of mills in the South more than doubled between 1890 and 1900, to 542. By 1938 Revolution Mill was the world’s largest factory exclusively making flannel, producing 50m yards of cloth a year.

The main mill building still has the springy hardwood floors and original wooden joists installed in its heyday, but no clacking of looms has been heard here for over three decades. The mill ceased production in 1982, an early warning of another revolution on a global scale. The textile industry was starting a fresh migration in search of cheaper labour, this time in Latin America and Asia. Revolution Mill is a monument to an industry that lost out to globalisation.

In nearby Thomasville, there is another landmark to past industrial glory: a 30-foot (9-metre) replica of an upholstered chair. The Big Chair was erected in 1950 to mark the town’s prowess in furniture-making, in which North Carolina was once America’s leading state. But the success did not last. “In the 2000s half of Thomasville went to China,” says T.J. Stout, boss of Carsons Hospitality, a local furniture-maker. Local makers of cabinets, dressers and the like lost sales to Asia, where labour-intensive production was cheaper.

The state is now finding new ways to do well. An hour’s drive east from Greensboro is Durham, a city that is bursting with new firms. One is Bright View Technologies, with a modern headquarters on the city’s outskirts, which makes film and reflectors to vary the pattern and diffusion of LED lights. The Liggett and Myers building in the city centre was once the home of the Chesterfield cigarette. The handsome building is now filling up with newer businesses, says Ted Conner of the Durham Chamber of Commerce. Duke University, the centre of much of the city’s innovation, is taking some of the space for labs.

North Carolina exemplifies both the promise and the casualties of today’s open economy. Yet even thriving local businesses there grumble that America gets the raw end of trade deals, and that foreign rivals benefit from unfair subsidies and lax regulation. In places that have found it harder to adapt to changing times, the rumblings tend to be louder. Across the Western world there is growing unease about globalisation and the lopsided, unstable sort of capitalism it is believed to have wrought.

A backlash against freer trade is reshaping politics. Donald Trump has clinched an unlikely nomination as the Republican Party’s candidate in November’s presidential elections with the support of blue-collar men in America’s South and its rustbelt. These are places that lost lots of manufacturing jobs in the decade after 2001, when America was hit by a surge of imports from China (which Mr Trump says he will keep out with punitive tariffs). Free trade now causes so much hostility that Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate, was forced to disown the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade deal with Asia that she herself helped to negotiate. Talks on a new trade deal with the European Union, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), have stalled. Senior politicians in Germany and France have turned against it in response to popular opposition to the pact, which is meant to lower investment and regulatory barriers between Europe and America.

Keep-out signs

The commitment to free movement of people within the EU has also come under strain. In June Britain, one of Europe’s stronger economies, voted in a referendum to leave the EU after 43 years as a member. Support for Brexit was strong in the north of England and Wales, where much of Britain’s manufacturing used to be; but it was firmest in places that had seen big increases in migrant populations in recent years. Since Britain’s vote to leave, anti-establishment parties in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Austria have called for referendums on EU membership in their countries too. Such parties favour closed borders, caps on migration and barriers to trade. They are gaining in popularity and now hold sway in governments in eight EU countries. Mr Trump, for his part, has promised to build a wall along the border with Mexico to keep out immigrants.

There is growing disquiet, too, about the unfettered movement of capital. More of the value created by companies is intangible, and businesses that rely on selling ideas find it easier to set up shop where taxes are low. America has clamped down on so-called tax inversions, in which a big company moves to a low-tax country after agreeing to be bought by a smaller firm based there. Europeans grumble that American firms engage in too many clever tricks to avoid tax. In August the European Commission told Ireland to recoup up to €13 billion ($14.5 billion) in unpaid taxes from Apple, ruling that the company’s low tax bill was a source of unfair competition.

Free movement of debt capital has meant that trouble in one part of the world (say, America’s subprime crisis) quickly spreads to other parts. The fickleness of capital flows is one reason why the EU’s most ambitious cross-border initiative, the euro, which has joined 19 of its 28 members in a currency union, is in trouble. In the euro’s early years, countries such as Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain enjoyed ample credit and low borrowing costs, thanks to floods of private short-term capital from other EU countries. When crisis struck, that credit dried up and had to be replaced with massive official loans, from the ECB and from bail-out funds. The conditions attached to such support have caused relations between creditor countries such as Germany and debtors such as Greece to sour.

Some claim that the growing discontent in the rich world is not really about economics. After all, Britain and America, at least, have enjoyed reasonable GDP growth recently, and unemployment in both countries has dropped to around 5%. Instead, the argument goes, the revolt against economic openness reflects deeper anxieties about lost relative status. Some arise from the emergence of China as a global power; others are rooted within individual societies. For example, in parts of Europe opposition to migrants was prompted by the Syrian refugee crisis. It stems less from worries about the effect of immigration on wages or jobs than from a perceived threat to social cohesion.

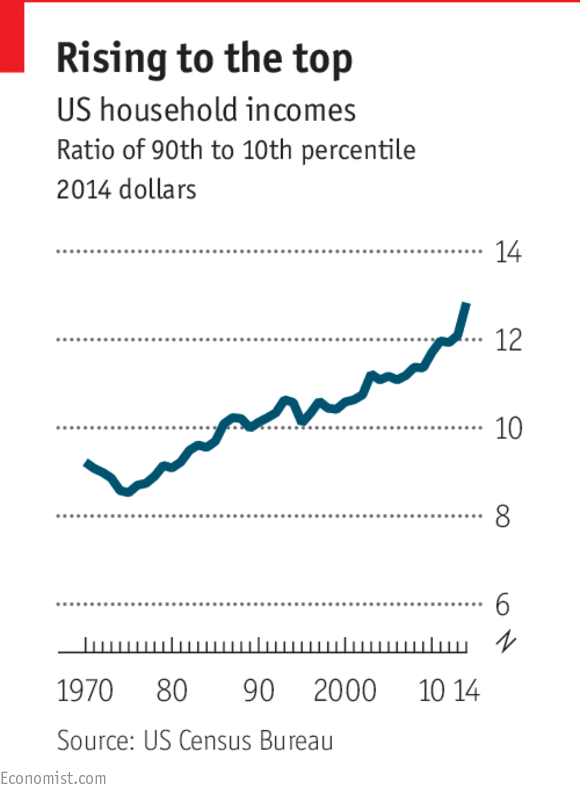

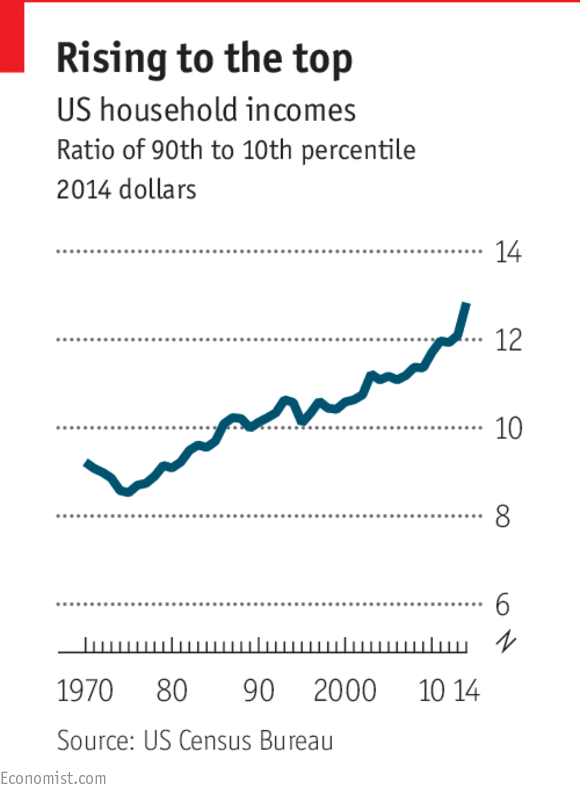

But there is a material basis for discontent nevertheless, because a sluggish economic recovery has bypassed large groups of people. In America one in six working-age men without a college degree is not part of the workforce, according to an analysis by the Council of Economic Advisers, a White House think-tank. In Britain, though more people than ever are in work, wage rises have not kept up with inflation. Only in London and its hinterland in the south-east has real income per person risen above its level before the 2007-08 financial crisis. Most other rich countries are in the same boat. A report by the McKinsey Global Institute, a think-tank, found that the real incomes of two-thirds of households in 25 advanced economies were flat or fell between 2005 and 2014, compared with 2% in the previous decade. The few gains in a sluggish economy have gone to a salaried gentry.

This has fed a widespread sense that an open economy is good for a small elite but does nothing for the broad mass of people. Even academics and policymakers who used to welcome openness unreservedly are having second thoughts. They had always understood that free trade creates losers as well as winners, but thought that the disruption was transitory and the gains were big enough to compensate those who lose out. However, a body of new research suggests that China’s integration into global trade caused more lasting damage than expected to some rich-world workers. Those displaced by a surge in imports from China were concentrated in pockets of distress where alternative jobs were hard to come by.

It is not easy to establish a direct link between openness and wage inequality, but recent studies suggest that trade plays a bigger role than previously thought. Large-scale migration is increasingly understood to conflict with the welfare policy needed to shield workers from the disruptions of trade and technology.

The consensus in favour of unfettered capital mobility began to weaken after the East Asian crises of 1997-98. As the scale of capital flows grew, the doubts increased. A recent article by economists at the IMF entitled “Neoliberalism: Oversold?” argued that in certain cases the costs to economies of opening up to capital flows exceed the benefits.

Multiple hits

This special report will ask how far globalisation, defined as the freer flow of trade, people and capital around the world, is responsible for the world’s economic ills and whether it is still, on balance, a good thing. A true reckoning is trickier than it might appear, and not just because the main elements of economic openness have different repercussions. Several other big upheavals have hit the world economy in recent decades, and the effects are hard to disentangle.

First, jobs and pay have been greatly affected by technological change. Much of the increase in wage inequality in rich countries stems from new technologies that make college-educated workers more valuable. At the same time companies’ profitability has increasingly diverged. Online platforms such as Amazon, Google and Uber that act as matchmakers between consumers and producers or advertisers rely on network effects: the more users they have, the more useful they become. The firms that come to dominate such markets make spectacular returns compared with the also-rans. That has sometimes produced windfalls at the very top of the income distribution. At the same time the rapid decline in the cost of automation has left the low- and mid-skilled at risk of losing their jobs. All these changes have been amplified by globalisation, but would have been highly disruptive in any event.

The second source of turmoil was the financial crisis and the long, slow recovery that typically follows banking blow-ups. The credit boom before the crisis had helped to mask the problem of income inequality by boosting the price of homes and increasing the spending power of the low-paid. The subsequent bust destroyed both jobs and wealth, but the college-educated bounced back more quickly than others. The free flow of debt capital played a role in the build-up to the crisis, but much of the blame for it lies with lax bank regulation. Banking busts happened long before globalisation.

Superimposed on all this was a unique event: the rapid emergence of China as an economic power. Export-led growth has transformed China from a poor to a middle-income country, taking hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. This achievement is probably unrepeatable. As the price of capital goods continues to fall sharply, places with large pools of cheap labour, such as India or Africa, will find it harder to break into global supply chains, as China did so speedily and successfully.

This special report will disentangle these myriad influences to assess the impact of the free movement of goods, capital and people. It will conclude that some of the concerns about economic openness are valid. The strains inflicted by a more integrated global economy were underestimated, and too little effort went into helping those who lost out. But much of the criticism of openness is misguided, underplaying its benefits and blaming it for problems that have other causes. Rolling it back would leave everyone worse off.

THERE IS NOTHING dark, still less satanic, about the Revolution Mill in Greensboro, North Carolina. The tall yellow-brick chimney stack, with red bricks spelling “Revolution” down its length, was built a few years after the mill was established in 1900. It was a booming time for local enterprise. America’s cotton industry was moving south from New England to take advantage of lower wages. The number of mills in the South more than doubled between 1890 and 1900, to 542. By 1938 Revolution Mill was the world’s largest factory exclusively making flannel, producing 50m yards of cloth a year.

The main mill building still has the springy hardwood floors and original wooden joists installed in its heyday, but no clacking of looms has been heard here for over three decades. The mill ceased production in 1982, an early warning of another revolution on a global scale. The textile industry was starting a fresh migration in search of cheaper labour, this time in Latin America and Asia. Revolution Mill is a monument to an industry that lost out to globalisation.

In nearby Thomasville, there is another landmark to past industrial glory: a 30-foot (9-metre) replica of an upholstered chair. The Big Chair was erected in 1950 to mark the town’s prowess in furniture-making, in which North Carolina was once America’s leading state. But the success did not last. “In the 2000s half of Thomasville went to China,” says T.J. Stout, boss of Carsons Hospitality, a local furniture-maker. Local makers of cabinets, dressers and the like lost sales to Asia, where labour-intensive production was cheaper.

The state is now finding new ways to do well. An hour’s drive east from Greensboro is Durham, a city that is bursting with new firms. One is Bright View Technologies, with a modern headquarters on the city’s outskirts, which makes film and reflectors to vary the pattern and diffusion of LED lights. The Liggett and Myers building in the city centre was once the home of the Chesterfield cigarette. The handsome building is now filling up with newer businesses, says Ted Conner of the Durham Chamber of Commerce. Duke University, the centre of much of the city’s innovation, is taking some of the space for labs.

North Carolina exemplifies both the promise and the casualties of today’s open economy. Yet even thriving local businesses there grumble that America gets the raw end of trade deals, and that foreign rivals benefit from unfair subsidies and lax regulation. In places that have found it harder to adapt to changing times, the rumblings tend to be louder. Across the Western world there is growing unease about globalisation and the lopsided, unstable sort of capitalism it is believed to have wrought.

A backlash against freer trade is reshaping politics. Donald Trump has clinched an unlikely nomination as the Republican Party’s candidate in November’s presidential elections with the support of blue-collar men in America’s South and its rustbelt. These are places that lost lots of manufacturing jobs in the decade after 2001, when America was hit by a surge of imports from China (which Mr Trump says he will keep out with punitive tariffs). Free trade now causes so much hostility that Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate, was forced to disown the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade deal with Asia that she herself helped to negotiate. Talks on a new trade deal with the European Union, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), have stalled. Senior politicians in Germany and France have turned against it in response to popular opposition to the pact, which is meant to lower investment and regulatory barriers between Europe and America.

Keep-out signs

The commitment to free movement of people within the EU has also come under strain. In June Britain, one of Europe’s stronger economies, voted in a referendum to leave the EU after 43 years as a member. Support for Brexit was strong in the north of England and Wales, where much of Britain’s manufacturing used to be; but it was firmest in places that had seen big increases in migrant populations in recent years. Since Britain’s vote to leave, anti-establishment parties in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Austria have called for referendums on EU membership in their countries too. Such parties favour closed borders, caps on migration and barriers to trade. They are gaining in popularity and now hold sway in governments in eight EU countries. Mr Trump, for his part, has promised to build a wall along the border with Mexico to keep out immigrants.

There is growing disquiet, too, about the unfettered movement of capital. More of the value created by companies is intangible, and businesses that rely on selling ideas find it easier to set up shop where taxes are low. America has clamped down on so-called tax inversions, in which a big company moves to a low-tax country after agreeing to be bought by a smaller firm based there. Europeans grumble that American firms engage in too many clever tricks to avoid tax. In August the European Commission told Ireland to recoup up to €13 billion ($14.5 billion) in unpaid taxes from Apple, ruling that the company’s low tax bill was a source of unfair competition.

Free movement of debt capital has meant that trouble in one part of the world (say, America’s subprime crisis) quickly spreads to other parts. The fickleness of capital flows is one reason why the EU’s most ambitious cross-border initiative, the euro, which has joined 19 of its 28 members in a currency union, is in trouble. In the euro’s early years, countries such as Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain enjoyed ample credit and low borrowing costs, thanks to floods of private short-term capital from other EU countries. When crisis struck, that credit dried up and had to be replaced with massive official loans, from the ECB and from bail-out funds. The conditions attached to such support have caused relations between creditor countries such as Germany and debtors such as Greece to sour.

Some claim that the growing discontent in the rich world is not really about economics. After all, Britain and America, at least, have enjoyed reasonable GDP growth recently, and unemployment in both countries has dropped to around 5%. Instead, the argument goes, the revolt against economic openness reflects deeper anxieties about lost relative status. Some arise from the emergence of China as a global power; others are rooted within individual societies. For example, in parts of Europe opposition to migrants was prompted by the Syrian refugee crisis. It stems less from worries about the effect of immigration on wages or jobs than from a perceived threat to social cohesion.

But there is a material basis for discontent nevertheless, because a sluggish economic recovery has bypassed large groups of people. In America one in six working-age men without a college degree is not part of the workforce, according to an analysis by the Council of Economic Advisers, a White House think-tank. In Britain, though more people than ever are in work, wage rises have not kept up with inflation. Only in London and its hinterland in the south-east has real income per person risen above its level before the 2007-08 financial crisis. Most other rich countries are in the same boat. A report by the McKinsey Global Institute, a think-tank, found that the real incomes of two-thirds of households in 25 advanced economies were flat or fell between 2005 and 2014, compared with 2% in the previous decade. The few gains in a sluggish economy have gone to a salaried gentry.

This has fed a widespread sense that an open economy is good for a small elite but does nothing for the broad mass of people. Even academics and policymakers who used to welcome openness unreservedly are having second thoughts. They had always understood that free trade creates losers as well as winners, but thought that the disruption was transitory and the gains were big enough to compensate those who lose out. However, a body of new research suggests that China’s integration into global trade caused more lasting damage than expected to some rich-world workers. Those displaced by a surge in imports from China were concentrated in pockets of distress where alternative jobs were hard to come by.

It is not easy to establish a direct link between openness and wage inequality, but recent studies suggest that trade plays a bigger role than previously thought. Large-scale migration is increasingly understood to conflict with the welfare policy needed to shield workers from the disruptions of trade and technology.

The consensus in favour of unfettered capital mobility began to weaken after the East Asian crises of 1997-98. As the scale of capital flows grew, the doubts increased. A recent article by economists at the IMF entitled “Neoliberalism: Oversold?” argued that in certain cases the costs to economies of opening up to capital flows exceed the benefits.

Multiple hits

This special report will ask how far globalisation, defined as the freer flow of trade, people and capital around the world, is responsible for the world’s economic ills and whether it is still, on balance, a good thing. A true reckoning is trickier than it might appear, and not just because the main elements of economic openness have different repercussions. Several other big upheavals have hit the world economy in recent decades, and the effects are hard to disentangle.

First, jobs and pay have been greatly affected by technological change. Much of the increase in wage inequality in rich countries stems from new technologies that make college-educated workers more valuable. At the same time companies’ profitability has increasingly diverged. Online platforms such as Amazon, Google and Uber that act as matchmakers between consumers and producers or advertisers rely on network effects: the more users they have, the more useful they become. The firms that come to dominate such markets make spectacular returns compared with the also-rans. That has sometimes produced windfalls at the very top of the income distribution. At the same time the rapid decline in the cost of automation has left the low- and mid-skilled at risk of losing their jobs. All these changes have been amplified by globalisation, but would have been highly disruptive in any event.

The second source of turmoil was the financial crisis and the long, slow recovery that typically follows banking blow-ups. The credit boom before the crisis had helped to mask the problem of income inequality by boosting the price of homes and increasing the spending power of the low-paid. The subsequent bust destroyed both jobs and wealth, but the college-educated bounced back more quickly than others. The free flow of debt capital played a role in the build-up to the crisis, but much of the blame for it lies with lax bank regulation. Banking busts happened long before globalisation.

Superimposed on all this was a unique event: the rapid emergence of China as an economic power. Export-led growth has transformed China from a poor to a middle-income country, taking hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. This achievement is probably unrepeatable. As the price of capital goods continues to fall sharply, places with large pools of cheap labour, such as India or Africa, will find it harder to break into global supply chains, as China did so speedily and successfully.

This special report will disentangle these myriad influences to assess the impact of the free movement of goods, capital and people. It will conclude that some of the concerns about economic openness are valid. The strains inflicted by a more integrated global economy were underestimated, and too little effort went into helping those who lost out. But much of the criticism of openness is misguided, underplaying its benefits and blaming it for problems that have other causes. Rolling it back would leave everyone worse off.

No matter what, there should be no war

Editorial in The Dawn

Nearly one and a half billion people in two countries — India and Pakistan — appear to be held hostage to conspiracy, rumour and reckless warmongering. That needs to stop, and it needs to stop immediately.

On Thursday, 11 days after the Uri attack and seemingly an eternity in Pak-India sabre-rattling and diplomatic tensions, another layer of confusion and chaos was added to one of the world’s most complicated bilateral relationships.

With the facts of the Uri attack yet to be established or shared with the world, a new, potentially larger, set of questions has now overshadowed an already fraught situation.

What happened along the Line of Control between midnight and early morning on Thursday is a story that Indian authorities appear to be very clear about and the Indian media has reported with relish. But virtually nothing has been independently confirmed about the events along the LoC, an area that is effectively cordoned off from the media in both countries and where the local population is unlikely to know the facts or be willing to speak candidly.

What is clear is that something did happen at several points along the LoC in the early hours of Thursday morning. At the very least, Pakistani and Indian forces exchanged fire in which two Pakistani soldiers died.

That is a sad, if long-standing, reality of the region: whenever tensions between the two countries are high, parts of the LoC see live ammunition fired, the lives of local populations disrupted and several casualties among security personnel and civilians.

Indeed, two summers ago, with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi newly installed in office, the LoC saw a series of skirmishes that progressively escalated until reaching crisis point around mid-October. That set of events was supposedly meant to herald the start of a new, so-called get-tough policy by India.

Eventually, better sense prevailed and by September 2015 the DG Rangers and DG Border Security Force met and agreed to renew the LoC ceasefire. The Pathankot attack earlier this year, which involved infiltration across the Working Boundary, did not materially change the situation along the LoC, but unrest in India-held Kashmir and the Uri attack appear to have done so.

At this point, it is imperative to establish the facts quickly. The wild cheering that greeted the government’s accounts of events in India may become a dangerous precedent and create a new set of expectations in a region where war in an overtly nuclear environment would be catastrophic for both countries.

Facts, however, would help nudge the situation towards de-escalation, given signalling from the Pakistani state and Indian government.

Pakistani policymakers, both civilian and military, have reacted sensibly, and appear to be resisting Indian attempts to bait Pakistan. But the media echo chamber — jingoistic, fiercely nationalistic and often removed from reality — can have unpredictable effects, especially when it comes to whipping up warlike sentiment among the populations of the two countries.

Quickly establishing two sets of facts, of events along the LoC on Thursday and the Uri attack, would switch a media narrative from punch and counter-punch and allow the two states to work on how to ratchet down tensions along the LoC.

The Modi government, despite its hawkish instincts and muscle-flexing, has indicated an awareness of the dangers of unrestrained rhetoric. Facts will help clear the miasma and introduce the necessary rationality into a debate that is increasingly unhinged.

Clearly, the problems in the region are not unilateral and one-directional. Pakistan has pursued flawed policies in the past and could do more to help end the menace of terrorism in the region. But this is not an area of straightforward cause and effect, nor are the broader issues of the Pak-India relationship of immediate relevance.

First and foremost, the priority of the leaderships of Pakistan and India should be to ensure that no matter what the circumstances and no matter what the concerns, the path to war is not taken.

India suffered a blow in Uri as it did in Pathankot. It has a right to expect justice and Pakistan has a responsibility to investigate any links to citizens of this country. But what has been unleashed in India since the seemingly exaggerated claims of so-called surgical strikes along the LoC is frightening and wildly destabilising.

If now is not a propitious time for a dialogue of peace, it is the time for some serious introspection.

Only a few days ago, the Indian prime minister talked of a joint war against poverty; he must now also resist the poverty of ideas and the temptation to take the low, dangerous road.

Nearly one and a half billion people in two countries — India and Pakistan — appear to be held hostage to conspiracy, rumour and reckless warmongering. That needs to stop, and it needs to stop immediately.

On Thursday, 11 days after the Uri attack and seemingly an eternity in Pak-India sabre-rattling and diplomatic tensions, another layer of confusion and chaos was added to one of the world’s most complicated bilateral relationships.

With the facts of the Uri attack yet to be established or shared with the world, a new, potentially larger, set of questions has now overshadowed an already fraught situation.

What happened along the Line of Control between midnight and early morning on Thursday is a story that Indian authorities appear to be very clear about and the Indian media has reported with relish. But virtually nothing has been independently confirmed about the events along the LoC, an area that is effectively cordoned off from the media in both countries and where the local population is unlikely to know the facts or be willing to speak candidly.

What is clear is that something did happen at several points along the LoC in the early hours of Thursday morning. At the very least, Pakistani and Indian forces exchanged fire in which two Pakistani soldiers died.

That is a sad, if long-standing, reality of the region: whenever tensions between the two countries are high, parts of the LoC see live ammunition fired, the lives of local populations disrupted and several casualties among security personnel and civilians.

Indeed, two summers ago, with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi newly installed in office, the LoC saw a series of skirmishes that progressively escalated until reaching crisis point around mid-October. That set of events was supposedly meant to herald the start of a new, so-called get-tough policy by India.

Eventually, better sense prevailed and by September 2015 the DG Rangers and DG Border Security Force met and agreed to renew the LoC ceasefire. The Pathankot attack earlier this year, which involved infiltration across the Working Boundary, did not materially change the situation along the LoC, but unrest in India-held Kashmir and the Uri attack appear to have done so.

At this point, it is imperative to establish the facts quickly. The wild cheering that greeted the government’s accounts of events in India may become a dangerous precedent and create a new set of expectations in a region where war in an overtly nuclear environment would be catastrophic for both countries.

Facts, however, would help nudge the situation towards de-escalation, given signalling from the Pakistani state and Indian government.

Pakistani policymakers, both civilian and military, have reacted sensibly, and appear to be resisting Indian attempts to bait Pakistan. But the media echo chamber — jingoistic, fiercely nationalistic and often removed from reality — can have unpredictable effects, especially when it comes to whipping up warlike sentiment among the populations of the two countries.

Quickly establishing two sets of facts, of events along the LoC on Thursday and the Uri attack, would switch a media narrative from punch and counter-punch and allow the two states to work on how to ratchet down tensions along the LoC.

The Modi government, despite its hawkish instincts and muscle-flexing, has indicated an awareness of the dangers of unrestrained rhetoric. Facts will help clear the miasma and introduce the necessary rationality into a debate that is increasingly unhinged.

Clearly, the problems in the region are not unilateral and one-directional. Pakistan has pursued flawed policies in the past and could do more to help end the menace of terrorism in the region. But this is not an area of straightforward cause and effect, nor are the broader issues of the Pak-India relationship of immediate relevance.

First and foremost, the priority of the leaderships of Pakistan and India should be to ensure that no matter what the circumstances and no matter what the concerns, the path to war is not taken.

India suffered a blow in Uri as it did in Pathankot. It has a right to expect justice and Pakistan has a responsibility to investigate any links to citizens of this country. But what has been unleashed in India since the seemingly exaggerated claims of so-called surgical strikes along the LoC is frightening and wildly destabilising.

If now is not a propitious time for a dialogue of peace, it is the time for some serious introspection.

Only a few days ago, the Indian prime minister talked of a joint war against poverty; he must now also resist the poverty of ideas and the temptation to take the low, dangerous road.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)