by R.Upadhyay

Shah Wali Ullah (1703-1762) was a Muslim thinker of eighteenth century. His time was one of the most emotional chapters of Islamic revivalist movements in Indian subcontinent. The on going Hindu-Muslim communal controversy in contemporary India is deeply rooted in his political Islamic theory. The most significant contribution of Wali Ullah (Allah) for his community is that his teachings kept alive the religious life of Indian Muslims linked with their inner spirit for re-establishment of Islamic political authority in India.

Historically, Wali Ullah's political thought was to meet the political need of his time, but its relevance in the changed social scenario is one of the most important reasons that Indian society is not free from the emotional disorder. If the society has not developed the attitude of let bygones of the dark history of Indian subcontinent be gone, then Wali Ullah's political Islam is also responsible for it. His emphasis on Arabisation of Indian Islam did not allow the emotional integration of Indian Muslims with rest of the population of this country. Regressively affecting the Muslim psyche, his ideology debarred it from a forward-looking vision. His political thought however, created " a sense of loyalty to the community among its various sects" ((The Muslim Community of Indo-Pakistan subcontinent by Istiaq Hussain Qureshi, 1985, page 99).

Born ( Muzaffarnagar-Uttar Pradesh) in a family loyal to Mogul Empire Wali Ullah claimed his lineage from Quraysh tribe of Prophet Mohammad and of Umar, the second caliph (Religion and Thought of Shah Wali Allah by J. M.S.Baljon - E.J. Brill 1986, page 1). Inheriting the Sufi tradition of Sunnism he succeeded his father after his death in 1719 as principal of Madrasa Rahimiyya at Delhi at the age of 14. He went for pilgrimage to Mecca and Madina in 1730 and pursued deep study of Hadith and Islamic scriptures during his 14 months stay there.

On his return to India from the epicentre of Islam in 1732, Shah Wali Ullah was found more concerned with the political disorder and fading glory of Muslim power. He wanted the Muslim society to return to the Prophet era for the political unity of the then Muslim rulers. His religio-political thought was based on the 'Perso -Islamic theory of kingship' (Shah Wali Ullah and his Time by Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi, page 397) and Mahmud Ghazna and Aurangzeb were his heroes among the Muslim rulers. His objective was to re-establish the Islamic cultural hegemony in the Indian sub-continent.

Shah Wali Ullah realised the political rise of non-Muslims like Maratha, Jat and Sikh powers and the fading glory of Islamic rule as danger to Islam and therefore, any loss of political heritage of Muslim was unbearable to him. He was the first Arab scion in India, who raised Islamic war cry for stalling the diminishing glory of Mogul Empire. His religio-political theory inspired a large number of successive Muslim scholars, who carried forward his mission and resultantly gave birth to Islamic politics in India. The slogan of 'Islam is in danger' - is profoundly embedded to his hate-non-Muslim ideology.

Wali Ullah "grew up watching the Mogul Empire crumble. His political ambition was to restore Muslim power in India more or less on the Mogul pattern (Aurangzeb not Akbar's model). Pure Islam must be re- enacted, a regenerated Muslim society must again be mighty" (Islam in Modern History by W.C.Smith, Mentor Book, 1957, page51-52).

In the face of the fading glory of Mogul Empire and indigenous resurgence of non-Islamic forces like Maratha, Jat and Sikh in Muslim dominated India Wali Ullah decided to re-evaluate the Muslim dilemma. He realised that sectarian divisions and dissensions in the community and struggle for power among the various Muslim rulers were the major factors responsible for the diminishing pride of Mogul Empire. Forging unity among them with an overall objective to restore political dominance of Islam therefore, became his intellectual priority. The main thrust of his extensive writings was to present an integrated view of various Islamic thoughts.

Giving a call for 'a return of true Islam' and asking the Muslims to go to the age of Quran and listen to its literal voice sincerely, Wali Ullah boldly asserted that " the Prophet's teachings were the result of the cultural milieu then prevalent. He opined that today (that is in his days) every injunction of the Shariat and every Islamic law should be rationally analysed and presented" (Muslim Political Issues and National Integration by H. A.Gani, 1978, page 184).

Being proud of his Arab origin Wali Ullah was strongly opposed to integration of Islamic culture in the cultural mainstream of the sub-continent and wanted the Muslims to ensure their distance from it. "In his opinion, the health of Muslim society demanded that doctrines and values inculcated by Islam should be maintained in their pristine purity unsullied by extraneous influences" (The Muslim Community of Indo-Pakistan subcontinent by Istiaq Hussain Qureshi, 1985, page 215). "Wali Ullah did not want the Muslims to become part of the general milieu of the sub-continent. He wanted them to keep alive their relation with rest of the Muslim world so that the spring of their inspiration and ideals might ever remain located in Islam and tradition of world community developed by it". (Ibid. page 216).

On principle Wali Ullah had no difference with his contemporary Islamic thinker Abd-al-Wahab (1703-1787) of Saudi Arabia, who had also launched an Islamic revivalist movement. Wahab, who is regarded as one of the most radical Islamists has a wide range of followers in India. He "regarded the classical Muslim law as sum and substance of the faith, and therefore, demanded its total implementation" (Qamar Hasan in his book - Muslims in India -1987, page 3).

Wali Ullah also supported the rigidity of Wahab for strict compliance of Shariat (Islamic laws), and shariatisation was his vision for Muslim India. He maintained that "in this area (India), not even the tiniest rule of that sharia should be neglected, this would automatically lead to happiness and prosperity for all" (Shah WaliUllah and his Time by Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi, 1980, page 300). However, his theory of rational evaluation of Islam was only a sugar quoted version of Islamic fundamentalism for tactical reasons. He was guided more due to the compulsion of the turbulent situation for Muslim rulers at the hands of non-Muslim forces around them than any meaningful moderation of Islam, which could have been in the larger interest of the subcontinent.

Glorifying the history of Muslim rule as triumph of the faith, WaliUllah attributed its downfall to the failure of the community to literal adherence to Islamic scriptures. His movement for Islamic revivalism backed by the ideology of Pan-Islamism was for the political unity of Indian Muslims. His religio-political ideology however, made a permanent crack in Hindu--Muslim relation in this sub-continent. Subsequently non-Muslims of the region viewed his political concept of Islam as an attempt to undermine the self-pride and dignity of integrated Indian society.

The religio-political theory of Wali Ullah was quite inspiring for Indian Muslims including the followers of Wahhabi movement. It drew popular support from the Ulama, who were the immediate sufferers from the declining glory of Muslim rule in the subcontinent. The popular support to his ideology "has seldom been equalled by any Muslim religious movement in South Asian subcontinent" (The Genesis of Muslim Fundamentalism in British India by Mohammad Yusuf Abbasi, 1987, page 5). He was of the view that the lost glory of the faith could be restored if the Muslims adhered to the fundamentals of Islam literally.

Contrary to Akbar's 'conciliatory' policies in the governance of multi-religious and multi-ethnic Indian society, Wali Ullah wanted "a return to the ideals of the first two successors of Prophet Muhammad" as the only answer to the social conflicts. Laying stress on adherence to "the orthodox religious principles of Sunnism" he was against seeking any cooperation from Hindus or even Shi'is (Shah Wali Allah and his Time by Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi, 1980, page394). He invited Ahmad Shah Abdali of Afghanistan to attack the Maratha in third battle of Panipat and advised his collaborator Najib al Dawla to launch jehad against Jats.

Eulogizing the barbaric persecution of non-Muslims in medieval India as glory of Islam, he did not believe in Indian nationhood or any national boundary for Muslims and therefore, invited Shah Abdali, Amir of Afghan to attack India (Third battle of Panipat 1761), in which Marathas were defeated. In his letter to the Afghan king he said, "…All control of power is with the Hindus because they are the only people who are industrious and adaptable. Riches and prosperity are theirs, while Muslims have nothing but poverty and misery. At this juncture you are the only person, who has the initiative, the foresight, the power and capability to defeat the enemy and free the Muslims from the clutches of the infidels. God forbid if their domination continues, Muslims will even forget Islam and become undistinguishable from the non-Muslims" (Dr. Sayed Riaz Ahmad in his book 'Maulana Maududi and Islamic state' - Lahore People's Publishing House, page 15 - 1976).

He further wrote:

"We beseech you in the name of Prophet to fight a jihad against the infidels of this region… The invasion of Nadir shah, who destroyed the Muslims, left the Marathas and Jats secure and prosperous. This resulted in the infidels regaining their strength and in the reduction of Muslim leaders of Delhi to mere puppets" ( Shah Wali Allah and his times by Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi, page page305).

He also instigated Rohillas leader Najib al Dawla against his Hindu employees alleging that they were sympathetic to Jats. "Shah WaliUllah pointed out that one of the crucial conditions leading to the Muslim decline was that real control of governance was in the hands of Hindus. All the accountants and clerks were Hindus. Hindus controlled the countries wealth while Muslims were destitute" ( Shah Wali Allah and his times by Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi, 1980, page 304). In his letter he advised Abdali for " orders prohibiting Holi and Muharram festivals should be issued" (Ibid. page, 299) exposed his hostility towards both Hindus and Shias.

Reminding the Muslim rulers of the dominant role of Muslims even in a multi-religious society Wali Ullah said, "Oh Kings! Mala ala urges you to draw your swords and not put them back in their sheaths again until Allah has separated the Muslims from the polytheists and the rebelious Kifirs and the sinners are made absolutely feeble and helpless" (Ibid. page 299)

Noted historian Dr. Tara Chand remarked:

"He (Wali Ullah) appealed to Najib-ud-Daulah, Nizamul Mulk and Ahmad Shah Abdali - all three the upholders of condemned system - to intervene and restore the pristine glory of Islam. It is amazing that he should have placed his trust in Ahmad Shah Abdali, who had ravaged the fairest provinces of the Mogul empire, had plundered the Hindus and Muslims without the slightest compunction and above all, who was an upstart without any root among his own people" (History of the Freedom Movement of India, volume I, 1970, page 180).

Even though the defeat of Marathas by Abdali could not halt the sliding decline of Mogul Empire, it made Wali Ullah the hero of Indian Muslims and he emerged as main inspiring force for Muslim politics in this country. His Islamic thought was regarded as saviour of the faith and its impact left a deep imprint on Indian Muslim psyche, which continues to inspire them even today. Almost all the Muslim organisations in this country directly or indirectly draw their political inspiration from Wali Ullah.

Wali Ullah died in 1762 but his son Abd al Aziz (1746-1823) carried his mission as a result India faced violent communal disorder for decades. Considering Indian subcontinent no longer Dar-ul-Islam (A land, where Islam is having political power) and British rule as Dar ul-Harb (A land, where Islam is deprived of its political authority), he laid emphasis on jehadi spirit of the faith. Saiyid Ahmad (1786-1831) of Rai Bareli a trusted disciple of Abd al Aziz launched jehad on the Sikh kingdom but got defeated and killed in battle of Balkot in May 1831. Tired with their failures in re-establishing Muslim rule the followers of Wali Ullah preferred to keep their movement in suspended animation for decades, when the Britishers established their firm grip on this country.

The Sepoy mutiny of 1857 was a turning point in the history of Islamic fundamentalism in India. With its failure Indian Muslims lost all hopes to restore Muslim power in India. But successive Ulama in their attempt to keep the movement alive turned towards institutionalised Islamic movement. Some prominent followers of Wahhabi movement like Muhammad Qasim Nanauti and Rashid Ahmad Gangohi drew furter inspiration from the religio-political concept of Wali Ullah and set up an Islamic Madrassa at Deoband in U.P. on May 30, 1866, which grew into a higher Islamic learning centre and assumed the present name of Dar-ul-Uloom (Abode of Islamic learning) in 1879. For last 135 years Dar-ul-Uloom, which is more a movement than an institution has been carrying the tradition of Wahabi movement of Saudi Arabia and of Wali Ullah of Delhi. Even Sir Sayid Ahmad drew inspiration from the tactical moderation of Islam from Walli Ullah in launching Aligarh movement. The Muslim politics as we see today in Aligarh Muslim University is deeply influenced with the Islamic thought of Wali Ullah.

Most of the Muslim scholars and Islamic historians have projected Wali Ullah 'as founder of Islamic modernism' and a reformer of faith because of his emphasis on rational evaluation of Shariat. His attempt to present an integrated view of the various schools of Islamic thought was however, more a tactical move for the political unity of Muslims to restore the political authority of Islam than for overall development of an integrated Indian society. His insistence for not diluting the cultural identity of Arab in a Hindu-majority environment shows that his so-called reform of Islam was only for a political motive. His obsession to extreme Sunnism of Sufi tradition exposes the theory of Islamic modernism. His political objective that followers of Islam should not lose their status of dominant political group in state Wali Ullah was against the concept of civilised democracy.

Contrary to his projected image of a reformer, Wali Ullah like other militant group of Islamic intellectuals did not appreciate any cultural and social reconciliation with non-Muslims in an integrated society. His communal bias against the political rise of non-Muslim powers like Maratha, Jat and Sikh goes against the theory that Wali Ullah was a Muslim thinker for Islamic moderation. His exclusivist theory favouring political domination of his community all over the world with starting point in India vindicates this point. In the background of his hate-Hindu political move, Wali Ullah may not stand the scrutiny of being a Muslim thinker for rational evaluation of Islam and its moderation.

By and large Muslim intellectuals have eulogized Wali Ullah that he was deeply hurt with the plight of his community particularly after "Nadir Shah's sack of Delhi and the Maratha, Jat and Sikh depredation" (The Muslim Community of Indo-Pakistan subcontinent by Istiaq Hussain Qureshi, 1985, page 199). But they ignored the communal bias of Wali Ullah, for whom Maratha, Jat and Sikh revolts were "external danger to the community". Wali Ullah hated Nadir Shah for his barbarous invasion but he was more so because of him being a Shia Muslim.

According to Dr. Sayed Riaz Ahmad, a Muslim writer, the Muslim leaders like Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Mohammad Iqwal, Abul A'la Maududi and others, who participated in freedom movement were followers of Wahhabi school and carried the tradition of Wali Ullah with slight re-adjustment. Thus, the nostalgic appeal to Muslim fundamentalism had a direct or indirect influence of Wali Ullah on the overall psyche of Indian Muslims. Unfortunately, the fundamentalist interpretation of Islam by Wali Ullah gradually widened the gap of mistrust between Hindus and Muslims of this sub-continent.

Creation of Pakistan was against the pan-Islamic concept of institutionalised fight for restoration of pure Islam. Dar-ul Uloom hardly made any attempt to abandon its pan-Islamic ideology and therefore, nationalist forces viewed its opposition to partition as a tactical move to ensure the growth of the institution by aligning with the freedom movement. Since Wahabi movement and Islamic thoughts of Wali Ullah did not sanction the concept of Indian nationalism, the claim of Dar-ul-Uloom that its leaders were 'nationalists' is not based on sound logic, as they always considered Islam above the nation.

Religion is by and large known as a path in search of spiritual truth but religious fundamentalism begins where spiritualism ends. Wali Ullah was confronted with the problem of division and dissension among the Muslim rulers. He wanted to bridge the sectarian gap within the community for restoration of the political glory of Islam and interpreted his faith accordingly. His interpretation of faith was hardly linked to any spiritual search even though it is contrary to his tradition of Sufism. The theory of Islamic moderation might have been helpful to his political objective but in long run it pushed Indian Muslims away from modern outlook and also created a dilemma for them. On the other hand it also created suspicion in non-Muslim world against this fourteen hundred-year-old religion. His suggestion for strict adherence to the precepts of Quran and Hadith practiced during the period of Prophet Mohammad and his Caliphs known as classical age of Islam ('622 AD to 845 AD') is still a major obstacle against modernisation of Indian Muslims.

Combination of Islamic extremism of Wahhab and religio-political strategy of Wali Ullah has become the main source of inspiration for Islamic terrorism as we see today. So long as the Muslim leaders and intellectuals do not come forward and re-evaluate the eighteenth century old interpretation of faith any remedy for resolution of on going emotional disorder in society is a remote possibility. It is the social obligation of intellectuals to awaken the moral and economic strength of entire society without any religious prejudice.

“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Thursday 2 January 2014

Artificially prolonged old age is the new iatrogenic malady. - When it's time to go, let me go, with a nice glass of whisky and a pleasing pill

Advances in science are keeping us alive for longer and longer, but we are denied the right to die with dignity. It is grotesque

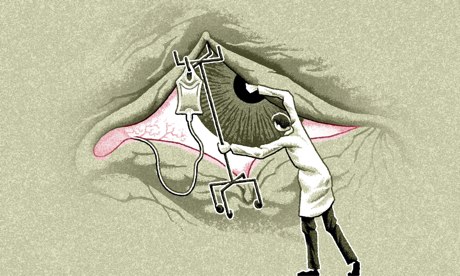

'Don't blame us if we are cluttering up the system. What we want and need is simple: a change in the law concerning assisted dying and voluntary euthanasia.' Illustration: Matt Kenyon

Back in the mid-70s, we were introduced to the notion of "medical nemesis" by the Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich. He warned us that doctors may do more harm than good, and that some diseases (which he labelled iatrogenic) were caused, not cured, by medical interventions. This doctrine has been widely accepted – we all know about the dangers of overprescribing antibiotics, about the risks of over-zealous or misinterpreted scans, about the creeping medicalisation of childbirth – but its application to old age and death is what interests me here. One of Illich's arguments in those days was that medicine, despite its apparent successes, was not notably increasing life expectancy. Alas, he was wrong. Artificially prolonged old age is the new iatrogenic malady.

We can't switch on the news without being told we will live longer, work longer, and survive on diminishing pensions or overpriced annuities. Newspaper columnists tell us we are selfish and that the young are suffering from our claiming an unfair share of state support. They begrudge us our bus passes, one of the few well-earned consolations of age. As we move into our unwanted last decade, we will, entirely predictably, become lonelier and lonelier and more and more likely to suffer from dementia and more and more expensive to maintain.

It would be unfair to blame doctors or health professionals for our longevity, which may be attributed to causes other than surgical ingenuity and pharmacological innovations and deadly life support machines, but it is not surprising that many of us feel gravely disappointed by the help and relief on offer to us at the end of life.

We look in vain for compassion, dignity, even common sense. We look in vain, despite what we are told, for adequate pain relief. Medical professionals seem far more interested in keeping alive barely viable premature "miracle" babies with a poor long-term prognosis than in offering reassurance to the growing and ageing multitudes who long to depart peacefully. They keep the babies alive because it's challenging, and very few people dare argue that it's not a good thing to do. They keep us alive because they are forbidden to give us what we want and need, and they are too frightened to question the law. There's something wrong there.

Don't blame us if we are cluttering up the system. What we want and need is simple. We want a change in the law concerning assisted dying and voluntary euthanasia, and help, if need be, to die with dignity.

The groundswell of opinion in favour of change is unmistakable. How often do you hear phrases like "you wouldn't let your dog suffer like that"? Three-quarters of the population backed Lord Falconer's assisted dying bill on its first reading in parliament. The bill would allow people who are terminally ill to receive the help they need to die, if that is what they choose. But can we have what we want? No. The politicians won't let us, the bishops won't let us, the health professionals aren't allowed to let us. It's grotesque.

Those suffering from incurable diseases need to be able to choose without penalty the help which they are at the moment denied. The elderly need to be able to plan ahead clearly, and to make their own choices about when their lives are no longer worth living. There seems to be some conspiracy to stop us thinking about the end game we all shall play. So we shuffle on, until it's too late to make any decisions at all, and we become helpless pawns in the politics of deferral, and utterly dependent on the humiliating procedures that for all our rational life we so wished to avoid.

It is my hope that in my lifetime the law will change, taking with it the fears that add so much terror to death. How wonderful it would be, if we knew that we would not be obliged to contemplate the bodily and mental decay that threatens us all. That we could opt out, and make our quietus, not with a bare bodkin or a plastic bag, or by jumping off the top of a multistorey car park, but with a nice glass of whisky and a pleasing pill – and so good night. How the heart would lift with joy at the good news. I don't go for Martin Amis's suicide booths, but I'm with Will Self all the way about the right to die when and how we want. When it's time to go, let's just go.

At the moment, it's not that easy. My husband, Michael Holroyd, fondly believes that as the longest serving patron of the Dignity in Dying campaigning organisation, he will be allowed to die in peace, but no, the doctors, in mortal fear of parliament, the law, the press and the General Medical Council, will be slavishly working to rule and obeying orders and striving officiously to keep him alive as they observe their archaic Hippocratic oath. It will be just like it was in the old days, when Simone de Beauvoir described her mother's death, in the ironically titled A Very Easy Death. If a woman of her intellect and clout couldn't prevent her mother from being hacked about by surgeons on her deathbed, what hope have we?

The best new year's gift an ageing population could receive is the right to die. As the philosopher Joseph Raz argues "The right to life protects people from the time and manner of their death being determined by others, and the right to euthanasia grants each person the power to choose themselves that time and manner." The right to die is the right to live.

Marijuana shoppers flock to Colorado for first legal recreational sales

'This is going to be a turning point in the drug war,' says one customer at a cannabis dispensary, 'a beginning of the peace'

- Rory Carroll in Denver

- theguardian.com,

The debut of the world's first legal recreational marijuana got off to a smooth and celebratory start with stores across Colorado selling joints, buds and other pot-infused products to customers from across the United States.

Throngs lined up from before dawn on Wednesday to be among the first to buy legal recreational marijuana at about three-dozen licensed stores, with cheers erupting when doors opened at 8am local time.

“It's a historical event. Everyone should be here,” said Darren Austin, 44, who drove from Georgia and joined a festive crowd gathered in falling snow outside Denver's 3-D Cannabis store. “This is going to be a turning point in the drug war. A beginning of the peace.”

His son Tyler, 21, held a sign saying “It's about time”. Like his father, he painted his face green. “I'm going to move to Colorado. Seriously,” said Darren.

Behind them waited Savannah Edwards, 21, a substitute teacher who drove overnight from Lubbock, Texas. “I'm here not so much for the marijuana as the history.” Just as people reminisced about Woodstock, she would be telling this story half a century from now, she said. “I've never been to a dispensary before. I don't even know what I'll buy.”

Colorado became the first jurisdiction in the world – beating Washington state and Uruguay by several months – to legalise recreational cannabis sales. Voters approved the measure in a ballot initiative in the November 2012 general election – a landmark challenge to decades of “drug war” dogma which could herald a shift as radical as the end of alcohol prohibition in 1933.

JD Leadam, 24, a bioplastics producer from Los Angeles, flew in just for the day. “This is the first time in the whole of the world that the process is completely legal. It's something that I can tell my kids about.”

After Washington, Alaska may follow suit later this year, with activists then targeting Arizona, California, Nevada and Maine, said Mason Tvert, director of communications for the Marijuana Policy Project. “Making marijuana legal for adults is not an experiment. Prohibition was the experiment and the results were abysmal,” he told a press conference.

Activists, customers and media gathered at the 3D Cannabis store for the first ceremonial sale. "It's 8am. I'm going to do it," said Toni Fox, the owner.

The first customer was Sean Azzariti, an Iraq war veteran who featured in pro-legalisation campaign ads. He bought an eighth of an ounce of an Indica strain called Bubba Kush and some marijuana-infused truffles. Total price, $59.74, including 21.22% sales tax.

State regulations insist every marijuana plant must be tracked from seed to sale but about 400,000 of the 2m tags sent in the post did not reach all stores in time. Authorities allowed licensed stores to sell regardless. The Denver Post called the glitch disappointing.

The three dozen stores that sold recreational pot on Wednesday will multiply in coming weeks. Regulators have issued 348 recreational pot licences: 136 for retail stores, 178 for cultivation, 31 for infused edibles and other spin-off products, and three for testing.

Cynthia Johnston, 69, bought two pre-rolled joints ($10 each) and an eighth of an ounce of Sour Diesel. “I've been working towards this moment since 1979,” she grinned. “Now, where can I smoke?”

Not in public spaces and not, according to notices which sprouted overnight, in many hotels. Pot must be consumed in private and cannot be transported over state lines, putting some restraints on the expected pot tourism boom.

Fears of joint-toking throngs in the street did not materialise by midday. Police said crowds were orderly and respectful. Denver City councilman Albus Brooks hailed their diversity and peacefulness.

As the first customers left the stores clutching their purchases jokes rippled across Twitter. “Curious if there has been a spike in Funyuns, Doritos and Taco Bell sales across Colorado today?” asked one.

Wednesday 1 January 2014

Finance's hold on our everyday life must be broken

The rampant capitalism that has brought the market into every corner of society needs to be reined in

‘Financial calculation evaluates everything in pennies and pounds, transforming the most basic goods – above all, housing – into "investments".’ Photograph: Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images

The mature economies of the modern world, particularly the United States and Britain, are often described as "financialised". The term reflects the ascendancy of the financial sector. Even more important, it conveys the penetration of the financial system into every nook and cranny of society, including housing, education, health and other areas of life that were previously relatively immune.

Evidence that financialisation represents a deep transformation of mature economies is offered by the global crisis of 2007-09. The crisis originated in the elephantine US financial system, and was associated with speculation in housing. For a brief period it led to serious questioning of mainstream economic theory and policy: how to confront the turmoil, and what to do about the diseased financial system; are new economic theories needed? However, after six years it is clear that very little has changed. Financialisation is here to stay.

Consider, for instance, the policies to confront the crisis. First, public funds were injected into banks to boost capital. Second, public liquidity was made available to banks to sustain their operations. Third, public interest rates were driven to zero to enable banks to make secure profits by lending to their own customers at higher rates.

This extraordinary public largesse towards private banks was matched by austerity and wage reductions for workers and households. As for restructuring finance, nothing fundamental has taken place. The behemoths that continue to dominate the global financial system operate in the knowledge that they enjoy an unspoken public guarantee. The unpalatable reality is that financialisation will persist, despite its costs for society.

Financialisation represents a historic and deep-seated transformation of mature capitalism. Big businesses have become "financialised" as they have ample profits to finance investment, rely less on banks for loans and play financial games with available funds. Big banks, in turn, have become more distant from big businesses, turning to profits from trading in open financial markets and from lending to households. Households have become "financialised" too, as public provision in housing, education, health, pensions and other vital areas has been partly replaced by private provision, access to which is mediated by the financial system. Not surprisingly, households have accumulated a tremendous volume of financial assets and liabilities over the past four decades.

The penetration of finance into the everyday life of households has not only created a range of dependencies on financial services, but also changed the outlook, mentality and even morality of daily life. Financial calculation evaluates everything in pennies and pounds, transforming the most basic goods – above all, housing – into "investments". Its logic has affected even the young, who have traditionally been idealistic and scornful of pecuniary calculation. Fertile ground has been created for neoliberal ideology to preach the putative merits of the market.

Financialisation has also created new forms of profit associated with financial markets and transactions. Financial profit can be made out of any income, or any sum of money that comes into contact with the financial sphere. Households, for example, generate profits for finance as debtors (mostly by paying interest on mortgages) but also as creditors (mostly by paying fees and charges on pension funds and insurance). Finance is not particular about how and where it makes its profits, and certainly does not limit itself to the sphere of production. It ranges far and wide, transforming every aspect of social life into a profit-making opportunity.

The traditional image of the person earning financial profits is the "rentier", the individual who invests funds in secure financial assets. In the contemporary financialised universe, however, those who earn vast returns are very different. They are often located within a financial institution, presumably work to provide financial services, and receive vast sums in the form of wages, or more often bonuses. Modern financial elites are prominent at the top of the income distribution, set trends in conspicuous consumption, shape the expensive end of the housing market, and transform the core of urban centres according to their own tastes.

Financialised capitalism is, thus, a deeply unequal system, prone to bubbles and crises – none greater than that of 2007-09. What can be done about it? The most important point in this respect is that financialisation does not represent an advance for humanity, and very little of it ought to be preserved. Financial markets are, for instance, able to mobilise advanced technology employing some of the best-trained physicists in the world to rebalance prices across the globe in milliseconds. This "progress" allows financiers to earn vast profits; but where is the commensurate benefit to society from committing such expensive resources to these tasks?

Financialisation ought to be reversed. Yet such an entrenched system will never be reversed by regulation alone. Its reversal also requires the creation of public banking that would operate with a new spirit of public service. It also needs effective controls to be applied to private banking as well as to international flows of capital. Not least, it requires new methods of meeting the financial requirements of households, as well as of small and medium enterprises. There is an urgent need for communal and associational ways to provide housing, education, health and other basic goods and services for working people, breaking the hold of finance on everyday life.

Ultimately, financialisation will not be reversed without an ambitious programme to re-establish the superiority of the social over the private, and the collective over the individual in contemporary society. Reversing financialisation is about reining in the rampant capitalism of our day.

Money has corrupted us. We no longer understand what it's worth

It's time we made money do what we want, rather than letting it diminish and degrade us

Money, what is it good for? Photograph: Getty Images

The house across the street has just gone on sale for £850,000. A bog-standard, late-Victorian, ex-council terrace house in the rough part of Islington, with a yard billed as a garden, costs as much as a street in Middlesbrough or Stoke.

When Marx wrote, in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, that money "is the visible divinity" involving "the transformation of all human and natural properties into their contraries, the universal overturning and confounding of things: it makes brothers of impossibilities", he wasn't predicting how the north London property market would heat up in 2013, but he was unwittingly prescient. What has happened to our moral and social values? Could they be more detached from monetary values? Or, hideously, are they accurately expressed by what money can buy?

Our task in 2014 is to stop this madness, get a grip on money, put a chokehold on Marx's visible divinity and make it do our bidding rather than what it's been doing for the past year: confounding, diminishing and degrading us. It'll be an unequal struggle: in this contest with the divine, we'll be like Jacob wrestling the angel.

But the imperative to resist our corruption by money has never been stronger. If our values are expressed by what money can buy, those values have gone nuts. In Harrods' new Fragrance Room you can buy a 7kg, faux-zebra-skin-wrapped candle scented in patchouli, cinnamon and candied lemon, "with spicy and woody notes which are subtly savage and masculine". Can candles smell savage and masculine, you ask? Probably not, but that's not the point. Aren't fur wrappings for candles a fire hazard? Probably, but again, not the point. Guess how much it costs: £599. Just the thing for all those blackouts that'll happen if Ed Miliband ever gets elected and fails to nationalise gas and electricity suppliers (as he should lickety split). At the other end of the scale, I was scandalised this summer that I couldn't find a Poundland or a 99p shop in Tenby. They'd been replaced by £1.20 shops – all the better to seasonally exploit, or so I theorised, tourist muppets like me.

Back to the property market. Who can afford £850k? Not the few council tenants who remain in this asset-stripped, right-to-buy-ravaged street. Certainly not thosesubsisting in increasing numbers on food banks, those who can't heat their homes or buy food because their budgets have been clobbered by the bedroom tax. Not even the hypocritical, owner-occupying locusts (including me) that swooped in during the aftermath of Thatcher's deracinating, spirit-crushing, community-wrecking property liberalisation.

Of all the piquant stories dramatising how in 2013 we have lost sense of our values, how money has not just corrupted us, but got away from our comprehension (think: the Saatchi household's unread five-figure credit card bills, the Co-op chief underestimating his bank's assets by tens of billions, the real world tragicomedies of the Bitcoinrevolution), none has seemed more personally relevant to me than this. This is a country of houses that scarcely anyone can afford. We have become degraded bit-part players in a street theatre of cruelty in which we are daily diminished by the prices of things we can't afford.

Many of us are unwitting monsters of conspicuous consumption, walking around with £500 iPhones or £270 Beats by Dre headphones, often through areas where consumer durables like those are not so much must-haves but never-will-haves. When a poor kid stole my iPhone in the street earlier this year, part of me got the theft equivalent of Stockholm syndrome – I felt that I deserved it. Which, as he told me during a restorative justice session months after his conviction for theft and robbery, I didn't.

As if to clinch this point about cruelly monetised street theatre, a two-bedroom house recently went on sale in London's West Hampstead for £300,000, billed as the cheapest freehold house in central London. Around 90 prospective buyers jammed into its little rooms, a queue formed outside and estate agents acted as bouncers – evicting prospective purchasers as if from an exclusive club. Which is what the property-owning class is. "The level of desperation is still there as the severe housing shortage in the city hasn't yet been solved," Lois Fort, head of residential lettings at Dutch & Dutch said.

We live in a country where you can run, but only pointlessly dream of catching up, where the majority of the poor (according to the latest government statistics) aren't the kind of people whom Iain Duncan Smith wants to terminate for the public good, but in work.

I say "we". Let's not get too pious about what the confusion of money has done to British society. We're not all in this together, despite what David Cameron says ("Never," as Arcade Fire sang, "trust a millionaire quoting the Sermon on the Mount"; never, they could have added, trust an Etonian plutocrat expressing solidarity with Cardboard City). Oh baby, I thought, as I clicked through the online photo gallery of the house for sale opposite – it's £300k more expensive than the last house to sell in this street! Our house may be worth as much! If not more! We're rich beyond our wildest dreams! By doing nothing! Or maybe not. Let's not go crazy: it hasn't sold yet.

Money has always been thus – whimsically making and unmaking fortunes, chucking out largesse irrespective of merit or desert and producing laughably misplaced expectations. Only now it seems more perverse, less graspable, wilder in its dispensations than ever.

Oscar Wilde once said: "Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing." Today we continue to know the value of nothing, but we don't know the price of anything either. We've got used to government ministers not knowing the price of a pint of milk, of David Cameron batting away inquisitorial probing about the price of a loaf by replying he prefers to bake his own in a bread maker, thanks very much.

Now we're getting used to more spectacular examples of monetary ignorance. When Paul Flowers, the disgraced chief executive of Co-op, appeared before the Commons treasury select committee and estimated the value of my bank's assets at £3bn (not far off, Reverend Flowers: the actual figure is £47bn), I wasn't sure how to feel or what to do. Was his evident grasp of the street value of ketamine, crystal meth and coke consoling in these circumstances for his customers or, you know, not? Should I transfer my overdraft and joke pension to First Direct (whatever that is) or convert it into Bitcoin currency (ditto), squirrel it away into offshore funds (whatever that means) or just hang tough (ditto)?

I did nothing, but felt heartened by Flowers' on-trend confusion – he was a kindred spirit, one confounded by money. Just a shame that his job description implied a competence at managing it. Mine doesn't, which is just as well. Whenever I'm asked the great imponderables – how many texts on your phone package, how did the Higgs Boson particle confer mass on the early universe, what's for tea – it's always the financial ones that drive me to make wild stabs in the dark like Flowers. How much does my mobile phone cost a month? Five pounds. Maybe £85. One or the other. I haven't got a grip on the stuff that's haemorraging from my current account. All I do know is that life is too short to spend time on comparison sites working out which of E.ON or npower proposes to rip me off less. The free market lie-dream of making capitalism work by developing informed choices about things (phone tariffs, gas bills, primary schools, hospitals, and – please God no – cars) that differ only fractionally isn't what I was put on this Earth for, whatever the government and Martin Lewis of moneysavingexpert.com say.

And I'm not alone in this. Many of us have become small-time Charles Saatchis. Among the many unpalatable things the millionaire art collector told Isleworth Crown Court during the trial of his and ex-wife Nigella Lawson's two assistants was that he didn't check his credit card bills. Like many of us, he values the time spent sitting in his pants eating beans from a tin pining for his departed domestic goddess much more than the nightmare of putting his finances in order. The only difference between him and us is that it doesn't matter if £76,000 a month is floating unnoticed out of his purview, while we get kneecapped by hired thugs if we don't repay payday loan companies the 50 quid we've borrowed on time (in so far as I understand their business models).

Spending has never been so easy, or so perilous. 2013 was the year that the bank issued me with a wave-and-go card. You hold it near a card reader, wave it like the Queen acknowledging her subjects from a limo, and suddenly you own seven flat whites you don't remember ordering and you're on a list somewhere saying you're no longer creditworthy. That's why, no doubt, there's a £20 limit on such contactless purchases – otherwise, I'd bring the banking system to collapse for a second time.

But, if you believe such Panglossian penseurs as Niall Ferguson, such financial innovations as contactless cards, PayPal, virtual currencies and replacing workers with self-scanning machines are handmaidens to human progress. "Far from being the work of mere leeches intent on sucking the life's blood out of indebted families or gambling with the savings of widows and orphans, financial innovation has been an indispensable factor in man's advance from wretched subsistence to the giddy heights of material prosperity that so many people know today," argued Ferguson in The Ascent of Money.

And the pub in east London where you can buy beer with the virtual currency Bitcoin, that is – somehow – part of that ascent of money? It is, argue enthusiasts, money by and for the people, a currency that arrived in 2009 at a time when trust in bankers was, as we all know, not buoyant. And it is possible to make real-money fortunes from Bitcoin that can be expressed in bricks and mortar. For example, four years ago Kristoffer Koch bought £22 worth of the virtual currency, which is usually used for online transactions. Such is Bitcoin's volatility that his investment, which he had forgotten about until reading reports of its rise in value last year, was worth $850,000. He cashed a fifth of that fortune in order to buy an apartment in one of Oslo's wealthier districts.

I know what you're thinking. "Oslo? Sheez. No way I'm living in Oslo when I've made my fortune from speculation in a currency I don't even understand. Have you seen how much a beer costs there?" But that's not really the point. The point is that Bitcoin is a virtual currency sustained by a Ponzi-like belief that it is not worthless, and unbacked by the banking sector, gold or any of the established underpinnings of monetary value. For those of us whose first experience of money was using halfpennies and threepenny bits to buy gobstoppers and pea-shooters (stop looking blank, younger readers), such a mutation is hard to understand – unless, that is, we accept the truth of what a banker explained to me this week, namely banking is, has always been and always will be a confidence trick.

James Howells was less fortunate than his Norwegian counterpart. Last summer the British IT worker chucked out his computer hard drive. Only one problem: it turned out that it contained the cryptographic key he needed to access a digital wallet containing 7,500 Bitcoins which, he realised probably with a tremble in his otherwise stiff upper lip, was worth £4m. He hadn't backed up his hard drive (we've all been there, right?). His story is the 2013 version of a bank robber's millions blown across fields from a moving train with the twist that nobody, not even children otherwise unoccupied during the school holidays, is going to find Howells' fortune. That said, virtual fortune hunters are reportedly rummaging through the landfill site where it ended up. They, like Captain Oates only more so, may be some time.

If our task in 2014 is to get a grip on money, here's one little attempt. The other day I went to the shop with a notepad and a daughter. My eight-year-old's homework task was to note down the prices of things and put them in order. As often happens when assisting with primary-school homework, I learned more than she did. I thought it was she who was living in a disadvantaged monetary fairyland where, because of the advent of the cashless society (across Europe now only 9% of transactions take place in cash; in the US it's 7%, according to Daniel Conaghan and Dan Smith's The Book of Money), she would struggle to know how much basic things cost since, unlike me, she had never had to count out the price of them in coins of the realm.

But it turns out that I am the greater financial ignoramus. Did you know that a pint of semi-skimmed milk is 49p? That you can buy a banana for 19p? How much the Saturday Guardian costs? Me neither. In an increasingly cashless society where we punch out our pin for sums that scarcely figure in our consciousness, it's easy to spend money without realising it.

Money has become for us what beer was for Homer Simpson – the cause of and solution to all of our problems. Can we make it just the solution? It seems unlikely.

Sledging's inevitable? That's just silly

The idea that trash talk is a by-product of competitiveness, and essential to spice up a contest, is laughable

Ed Smith

January 1, 2013

The marketers would have us think that the public loves scenes like this © Getty Images

At a recent social event I bumped into a fast bowler who I'd played against many times. It was the first time I'd seen him since my retirement, and at first I couldn't work out what was odd about the conversation. He seemed sheepish, unable to look me in the eye, embarrassed about something. But what? As he was still playing the game professionally, I tried to draw him out about how things were going. "As you'll remember," he eventually replied, nervously, "I'm an idiot on the pitch, but I'm working on that these days." The point, however, is that I didn't remember. I had completely forgotten that he had sledged quite a bit. He'd remembered, I'd forgotten.

We should recast the debate about sledging. It is not about the sledged or so-called "victim", who is usually completely unaffected. It concerns the values and standards of the sledger. How does he want to live his life? It was the boxer Floyd Patterson, I think, who said that "trash talk" (as boxers call sledging) is easy - the hard thing for lippy fighters was accidentally bumping into an opponent with his wife and kids at the airport.

The fourth Test, in Melbourne, was not an especially fractious affair, though it had the occasional silly moment. So this column is not specifically about the last Test, nor even targeted only at this Ashes series. Instead, I want to expose some of the myths that threaten to undermine the sport we all love. It is time to ask a simple question: who are the real victims of sledging?

There is a nasty little theory going around that Michael Clarke and his Australians have "toughened up" this series and that their improved performance is somehow bound up with this hardening of their external behaviour. Thus the diplomatic, pointedly courteous Clarke who led Australia to defeat in the English summer is reincarnated as an Aussie battler with a sharp tongue and a nasty streak in the victorious campaign of 2013-14. It is a seductive theory, just the kind of easy, populist history that displaces complex truths with simplistic myths.

I see the causal chain working in the opposite direction. It is not sledging that leads to winning, it is winning that leads to sledging. Ironically, that makes it worse. Far from being an explanation of success, it is simply a failure of grace and dignity. Far from being a subtle strategic art, sledging is just an embarrassing version of playground bullying. The people with the real problems are the players who lose their dignity. Within education, in schools suffering outbreaks of bullying, improved behaviour often follows from asking the bullies themselves how they can be helped to get over their evident psychological problems. The focus, quite rightly, is on their inadequacies.

England, apparently, had quite a bit to say for themselves during their 3-0 victory. Now Australia have relished an opportunity to talk down to England while they have been playing above them. What guts, what bravery! To swear at opponents when they can't get a run or a wicket!

There is a lot of selective history about "toughness" and superficial behaviour. The fact that Allan Border's Australia lost in 1985 and won in 1989 is often framed by reference to his famous quote, "I'm sick of being seen as a good bloke and losing. I'd rather be a prick and win." But in terms of explaining the crucial improvements in 1989, I would look first at the 41 wickets of Terry Alderman and the 1345 runs that came from the bats of Steve Waugh and Mark Taylor.

The way sportsmen perform is determined by the complex interaction of skill, talent, resilience and context. The way they behave is simply a personal choice. And many of the greatest players, in all sports, have chosen to behave very well. Garry Sobers, Don Bradman and Rahul Dravid did not sledge the bowlers they dismantled, any more than Michael Holding sledged the batsmen he terrorised. There is scarcely a scrap of critical evidence to pin against the behaviour of Rod Laver, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal on the tennis court.

Nadal is arguably the toughest competitor, both mentally and physically, in any sport in the world. Toughness, of course, is playing at the limit of your capacity as often as possible. Yet nothing could be more ridiculous than the idea that Nadal would become tougher by unleashing a stream of abuse at Andy Murray just before the start of a match. And yet that is exactly the presumption of people who believe in a correlation between sledging and toughness.

Which leads me to another of cricket's self-destructive myths: that demeaning behaviour is inevitable, that it is the logical result of "market forces" and "the pressures of modern professional sport". Not true. Last January, I met up with Brad Drewett, then chief executive of the ATP, at the Australian Open in Melbourne. Drewett was dying from motor neurone disease, and the meeting had the poignant subtext that it was likely to be the first and last time we would meet.

Drewett described how the impressive culture at the top of men's tennis today is unrecognisable from his own time as a player in the 1980s. Back then, flashy rivalries degenerated into personal contemptuousness and many big guns treated the junior players with dismissive disdain. With the tantrums and outbursts of John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors, tennis was indulging the idea that "nice guys finish last".

"Roger Federer helped to change all that," Drewett explained, "and Rafael Nadal fitted in with the standards he set. After them, everyone had to follow their example."

| Far from being a subtle strategic art, sledging is just an embarrassing version of playground bullying. The people with the real problems are the players who lose their dignity | |||

Following the trajectory of the 1980s, tennis today ought to be an uninterrupted expletive-ridden tantrum. But it hasn't happened. Quite the reverse. A few good men radically altered the course of a whole sport. They changed the image of being a winner. They enhanced the expectations that follow from being a champion. And they will pass on to the next generation a sport in better health than the fractious environment they inherited. Alongside all their other achievements, Federer and Nadal disproved one of the silliest myths of professional sport: that there is some competitive disadvantage in being a decent person. In doing so, they demonstrated a truth rarely acknowledged: cultures are always in flux; they can improve as well as decline.

This fact has eluded not just cricketers but also broadcasters, and worst of all, even administrators. Pundits routinely opine that undignified behavior "adds spice to the contest" and "makes the sport dramatic to the viewer". Has anyone asked the public? The reply follows: "But look at the huge crowds at the MCG and encouraging TV viewing figures. Our brand strategy must be working!"

Well, a few new people with low attention spans are temporarily attracted to vulgarity, just as drivers slow down to look at car crashes on the other side of the road. But for the silent majority, cricket's past and cricket's future, the sport is not enhanced by macho posturing, it is demeaned by it.

The brand experts are mostly quack salesmen who know nothing at all about real brand value. Indeed, the phony profession of brand marketing is only a few decades old. In contrast, real brands - such as the Ashes, for example - have been around a lot longer than the whole concept of "branding".

Anyone who really understands brands - whether it is a business, a reputation or a family name - knows that they are very hard to build but all too easy to destroy. By legitimising playground bullying - indeed celebrating it - cricket believes it is winning some subliminal battle for relevance, for modernity, for a share of the sporting market.

I am not a brand expert, but I have a sense for how sports grow and evolve. And how they can decay and wither. Lowering behavioural expectations will not heighten interest in cricket, not over the long term. Only good cricket can do that.

DRS in the parallel universe

JANUARY 1, 2014

Jon Hotten in Cricinfo

Jon Hotten in Cricinfo

India may not use DRS, but the decisions they receive from umpires today are tinged with a DRS worldview © Getty Images

Enlarge

The theory of multiple universes was developed by an academic physicist called Hugh Everett. He was proposing an answer to the famous paradox of Schrödinger's Cat, a thought experiment in which the animal is both alive and dead until observed in one state or the other.

Everett's idea was that every outcome of any event happened somewhere - in the case of the cat, it lived in one universe and died in another. All possible alternative histories and futures were real. It was a mind-bending thought, but then the sub-atomic world operates on such scales. Everett's idea was dismissed at first, and wasn't accepted as a mainstream interpretation in its field until after his death in 1982. Like most theories in physics, its nature is essentially ungraspable by the layman - certainly by me - but superficially it chimes with one of the sports fan's favourite question, the "what-if". And after all, the DRS has produced a moment when a batsman can be both in and out to exactly the same ball.

There came a point during the fourth Test in Melbourne, as Monty Panesar bowled to Brad Haddin with Australia at 149 for 6 in reply to England's 255, when Monty had what looked like a stone-dead LBW shout upheld. Haddin reviewed, as the match situation demanded he must, and the decision was overturned by less than the width of a cricket ball.

In the second Test in Durban, Dale Steyn delivered the first ball of the final day to Virat Kohli with India on 68 for 2, 98 runs behind South Africa. The ball brushed his shoulder and the umpire sent him on his way. India don't use DRS, and so the on-field decision stood.

When the fans of the future stare back through time at the scorecards of both games, they will look at wins by wide margins - eight wickets for Australia and ten wickets for South Africa. They might not notice these "what-if" events.

Yet it's worth a thought as to what might have happened should England have had another 50 or 60 runs in the bank on first innings, and India the in-form Kohli at the crease to take the morning wrath of Steyn. Test cricket has a capacity to develop thin cracks into chasms as wide as the cracks in a WACA pitch, and the game is full of subtle changes that discharge their payload further down the line.

The thought that somewhere out there is a universe without DRS for England and with it for India is no consolation to the losing sides, but such moments highlight the ongoing flux within the system.

As soon as Kohli was fired out, Twitter was filled with comments along the lines of: "Bet they wish they had DRS now", but as one voice amongst the clamour noted: "India don't deserve poor umpiring because they don't want DRS."

That point had weight. Even in games without the system it retains its impact because it has reshaped the way umpires and players approach the game. India will, for example, still have batsmen given out leg before wicket while stretching well down the pitch in the post-DRS manner, because the worldview of the umpire has been changed by what he has seen on its monitors. Players bat and bowl differently, and umpires give different decisions, because of what DRS has shown them.

The retirement of Graeme Swann was something of a milestone in this respect. His career would have been significantly altered had he not been such a master of exploiting the conditions created by DRS. He knew how to bowl to get front-foot LBW decisions. In response, batsmen have had to adapt their techniques when playing spin bowlers.

In this way and in others, DRS has become knitted into the fabric of Test cricket, whether it is being used or not. Were it to be withdrawn now, its effects would still exist, and irrevocably so.

But India's aversion still has its merits. It's now thuddingly obvious that DRS will never be used for its original purpose, the eradication of the obvious mistake. Instead, it has, in a classic case of function-creep, become the sentry of the fine margin, inserting itself into places where its own deficiencies are highlighted. The Ashes series in England was inflamed by a malfunctioning Hotspot. The Ashes series in Australia has revealed that umpires no longer seem to check the bowler for front-foot no-balls.

The outsourcing of DRS technology remains a paradox worthy of Schrödinger. TV companies have to pay for it, and the developers of the system have a commercial reason to stress its accuracies. Such truths sit uneasily with the notion of fairness and impartiality. Similarly, players have been radicalised into ersatz umpires, having to choose whether or not to have decisions made. Such randomness also impinges on impartiality.

It's hard to think of something more implacable as a piece of machinery, and yet cricket has found a way to politicise it, and it's this, at heart, where India's objections lay. They have a point.

.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)