December 5, 2011

Posted by Anantha Narayanan 1 hour, 10 minutes ago in Tests - bowling

Five-wicket hauls in Tests: a look across and deep - part one

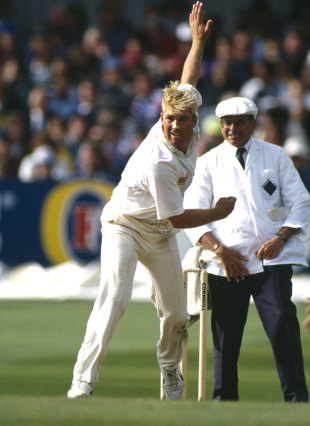

Michael Holding: 14 wickets on a flat track at The Oval in 1976

© Getty Images

Michael Holding: 14 wickets on a flat track at The Oval in 1976

© Getty Images

There is a tendency to ignore the bowlers in Test cricket. I myself am

guilty of this and do not allocate equal time and effort for these

forgotten species. This time I have decided to make amends by doing the

article on fifers in Test cricket immediately after I finished the one

on Test hundreds.

First, the term used. Let me reproduce the Wikipedia entry below.

Five-wicket haul (also Five-for, five-fer, fifer, or shortened to 5WI or FWI)

Five or more wickets taken by a bowler in an innings, considered a very

good performance. The term fifer is an abbreviation of the usual form of

writing bowling statistics, e.g. a bowler who takes 5 wickets and

concedes 117 runs is said to have figures of "5 for 117" or "5-117".

Sometimes called a "Michelle", after actress Michelle Pfeiffer.

I like the term "Fifer". However since that also refers to the

foot-soldier who plays the "Fife", the Scottish flute, I am somewhat

reluctant. "Pfeiffer" would be injudicious. I am not too comfortable

with "Five-for", being slightly contrived and seemingly incomplete. So I

will stick with "fifer", a single non-hyphenated (!!!) word and my

favourite. Much better than "DLF maximum" or "Karbonn Kamaal Katch".

Some maxims have to be repeated in EVERY article since quite a few

readers have a one-track mind and see what only they want to see.

This is not a Bowling Ratings article.

The ordering is based on an indicated measure and is visible to the

reader clearly. Do not draw any unintended inferences and come out with

comments based on those. There is no personal discretion involved other

than setting up the parameters. In view of the size of the articles and

number of tables, I have kept my narratives to a minimum.

Test Bowling is a fascinating subject. It is far more nuanced that Batting when it comes to analysis.

- The number of wickets in an innings is strictly limited to 10.

- Bowling successes are very clearly defined and measurable in terms of wickets (who and when) and accuracy.

- Bowling is three-dimensional: balls, runs and wickets. These three dimension-related values are available for

all bowling spells. (Batting is also three-dimensional: runs, time, balls. Unfortunately only runs information is available for all matches.)

- Batsmen win and save matches. Bowlers, almost always, win matches.

They rarely draw matches, a la Atherton, Hanif et al. But you will be

surprised: wait for the next article !!! A great ODI team can be founded

on top-class batting and average bowling, not a great Test team.

- 5 batsmen can score hundreds in an innings, and have done so. Only two bowlers can capture 5 wickets each in an innings.

All these nuances lead to a more exciting analysis of fifers.

It took me nearly a week to think of all possibilities, write the

program, prepare the tables and then weave the article around the

tables. I did so much work on the keyboard that my legs (yes, you read

it correctly) started aching. This turned out to be the longest article I

had ever done, barring none. So I decided to release this in two parts.

This will also enable me to do some specialized requests and add those

tables. At the end of the article, I have indicated the types of

analysis which have been included in Part 2. Even now, the current

article has been exceeded in size by only one article, the one published

last, on Special hundreds.

A note on the tables. I have standardized the presentation to have the

first 14 columns common. These are self-explanatory. I have shown

Home/Away (H/A), Bowling Type (S for spinners), innings bowled in and

Result (W for Win, = for draw and * for loss).

First the basic table. I did not do this for the hundreds. However it is

necessary to start with this table in the bowling analysis since many

readers may not be familiar with all these performances.

1. 9+ wicket bowling performances in Tests

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R

0428 1956 Eng Aus-205/10 H Laker J.C S 3 51.2-23- 53-10 W

1443 1999 Ind Pak-207/10 H Kumble A S 4 26.3- 9- 74-10 W

0048 1896 Eng Saf-151/10 A Lohmann G.A 2 12.0- 6- 28- 9 W

0428 1956 Eng Aus- 84/10 H Laker J.C S 2 16.4- 4- 37- 9 W

1583 2002 Slk Zim-236/10 H Muralitharan M S 1 40.0-19- 51- 9 W

1029 1985 Nzl Aus-179/10 A Hadlee R.J 1 23.4- 4- 52- 9 W

1081 1987 Pak Eng-175/10 H Abdul Qadir S 1 37.0-13- 56- 9 W

1266 1994 Eng Saf-175/10 H Malcolm D.E 3 16.3- 2- 57- 9 W

1423 1998 Slk Eng-181/10 A Muralitharan M S 3 54.2-27- 65- 9 W

0483 1959 Ind Aus-219/10 H Patel J.M S 2 35.5-16- 69- 9 W

0967 1983 Ind Win-201/10 H Kapil Dev N 3 30.3- 6- 83- 9 *

0849 1979 Pak Aus-310/10 A Sarfraz Nawaz 4 47.2- 7- 86- 9 W

0683 1971 Win Ind-352/10 H Noreiga J.M S 2 49.4-16- 95- 9 *

0461 1958 Ind Win-222/10 H Gupte S.P S 1 34.3-11-102- 9 *

0131 1913 Eng Saf-231/10 A Barnes S.F 3 38.4- 7-103- 9 W

0437 1957 Saf Eng-214/10 H Tayfield H.J S 4 49.2-11-113- 9 W

0138 1921 Aus Eng-315/10 H Mailey A.A S 3 47.0- 8-121- 9 W

I have limited this to bowling spells in which the bowler captured 9 or

more wickets. Only twice have bowlers captured all 10 wickets. Jim

Laker's feat came 79 years and 427 Tests after Alfred Shaw bowled the

first ball to Charles Bannerman. Anil Kumble's feat came a further 1015

Tests and 43 years after Laker dismissed Len Maddocks. I wonder how many

years would pass before this happens again: let me say, around 2050.

Laker had another 9-wicket haul,

in the same match. Muttiah

Muralitharan is the only other bowler to capture 9-wkts in an innings

twice. Quite surprisingly, the three spinners, Muralitharan, Abdul Qadir

and Subhash Gupte, captured 9 wickets on the first day. Another

wonderful spinner, Hugh Tayfield's 9 for 113 was adjudged to be the best

ever bowling performance in the Wisden-100 analysis. More of this

performance later. Kapil Dev, Gupte and Jack Noreiga all captured

9-wickets in an innings, in vain. Surely let us all agree that no one, I

repeat no one, in the next 1000 years, if Test cricket survives that

far, would capture all 20 wickets in a match.

Now for something I think is very important, performance away from home.

2. Wonderful performances, away from home

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R

0048 1896 Eng Saf-151/10 A Lohmann G.A 2 12.0- 6- 28- 9 W

1029 1985 Nzl Aus-179/10 A Hadlee R.J 1 23.4- 4- 52- 9 W

1423 1998 Slk Eng-181/10 A Muralitharan M S 3 54.2-27- 65- 9 W

0849 1979 Pak Aus-310/10 A Sarfraz Nawaz 4 47.2- 7- 86- 9 W

0131 1913 Eng Saf-231/10 A Barnes S.F 3 38.4- 7-103- 9 W

0047 1896 Eng Saf- 30/10 A Lohmann G.A 4 8.1- 5- 7- 8 W

0032 1889 Eng Saf- 43/10 A Briggs J S 3 9.4- 5- 11- 8 W

0104 1909 Aus Eng-119/10 A Laver F 2 18.2- 7- 31- 8 =

0026 1887 Eng Aus- 84/10 A Lohmann G.A 2 16.4-12- 35- 8 W

1370 1997 Aus Eng- 77/10 A McGrath G.D 1 20.3- 8- 38- 8 =

1398 1998 Eng Win-191/10 A Fraser A.R.C 2 16.1- 2- 53- 8 *

0699 1972 Aus Eng-116/10 A Massie R.A.L 3 27.2- 9- 53- 8 W

0131 1913 Eng Saf-160/10 A Barnes S.F 1 26.5- 9- 56- 8 W

0036 1892 Eng Aus-145/10 A Lohmann G.A 1 43.2-18- 58- 8 *

1341 1996 Saf Ind-137/10 A Klusener L 4 21.3- 4- 64- 8 W

0074 1902 Aus Eng-183/10 A Trumble H S 2 31.0-13- 65- 8 *

0079 1904 Eng Aus-111/10 A Rhodes W S 4 15.0- 0- 68- 8 W

0863 1979 Pak Ind-126/10 A Sikander Bakht 2 21.0- 3- 69- 8 =

1804 2006 Slk Eng-190/10 A Muralitharan M S 4 30.0-11- 70- 8 W

1307 1995 Saf Zim-283/10 A Donald A.A 3 33.0-12- 71- 8 W

1258 1994 Eng Win-304/10 A Fraser A.R.C 2 28.5- 7- 75- 8 W

0769 1976 Ind Nzl-215/10 A Prasanna E.A.S S 3 30.4- 5- 76- 8 W

0082 1904 Eng Aus-247/10 A Braund L.C S 1 29.1- 6- 81- 8 *

1027 1985 Slk Pak-259/10 A Ratnayeke J.R 2 23.2- 5- 83- 8 *

0699 1972 Aus Eng-272/10 A Massie R.A.L 1 32.5- 7- 84- 8 W

0947 1983 Ind Pak-323/10 A Kapil Dev N 1 30.5- 7- 85- 8 =

0738 1974 Eng Win-305/10 A Greig A.W 2 36.1-10- 86- 8 W

0781 1976 Win Eng-435/10 A Holding M.A 2 33.0- 9- 92- 8 W

0057 1898 Eng Aus-239/10 A Richardson T 2 36.1- 7- 94- 8 *

0323 1950 Win Eng-312/10 A Valentine A.L S 1 50.0-14-104- 8 *

1032 1985 Ind Aus-381/10 A Kapil Dev N 1 38.0- 6-106- 8 =

1797 2006 Aus Bng-427/10 A MacGill S.C.G S 1 33.3- 2-108- 8 W

0179 1929 Eng Aus-336/10 A White J.C S 4 64.5-21-126- 8 W

1020 1985 Aus Eng-482/ 9 A McDermott C.J 2 36.0- 3-141- 8 =

1680 2004 Ind Aus-474/10 A Kumble A S 2 46.5- 7-141- 8 =

1892 2008 Aus Ind-441/10 A Krejza J.J 1 43.5- 1-215- 8 *

In view of the importance of this classification, I have lowered the

cut-off to 8 wicket captures at the risk of going beyond my self-imposed

limit of 25 table entries. The table is ordered by the bowling

performance.

George Lohmann, on those uncovered pitches of yonder, crossed 8 wickets

mark no fewer than four times. Quite a few achieved this twice. Barnes,

Fraser, Kapil Dev, Massie (in the same match) and Muralitharan. The

9-wicket captures of Hadlee, Muralitharan and Sarfraz Nawaz are probably

the pick of the lot, all resulting in winning matches. Sarfraz, to

boot, in the last innings. The last time this was done, was by an

off-spinner on a baptism debut of fire in India.

Now for some special selections. The bowlers who captured the top-six batsmen.

3. Bowling spells in which top six wickets are captured - 1

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R BA-T Avge

0235 1934 Aus Eng-627/ 9 A O'Reilly W.J S 1 59.0- 9-189- 7 = 297 49.5

0461 1958 Ind Win-222/10 H Gupte S.P S 1 34.3-11-102- 9 * 262 43.7

1804 2006 Slk Eng-190/10 A Muralitharan M S 4 30.0-11- 70- 8 W 258 43.1

0990 1984 Eng Win-245/10 H Botham I.T 2 27.4- 6-103- 8 * 256 42.6

0754 1975 Eng Aus-304/10 A Underwood D.L S 1 38.4- 3-113- 7 * 254 42.3

1110 1988 Aus Win-349/ 9 H Hughes M.G 3 37.0- 9- 87- 8 * 254 42.3

1443 1999 Ind Pak-207/10 H Kumble A S 4 26.3- 9- 74-10 W 250 41.7

0913 1981 Aus Pak-500/ 8 H Yardley B S 1 66.0-16-187- 7 * 248 41.3

1726 2004 Aus Pak- 72/10 H McGrath G.D 4 16.0- 8- 24- 8 W 244 40.7

1028 1985 Slk Pak-295/10 A de Mel A.L.F 2 22.0- 1-109- 6 * 240 40.0

0765 1975 Win Aus-169/10 A Roberts A.M.E 3 18.4- 3- 54- 7 W 235 39.2

1029 1985 Nzl Aus-179/10 A Hadlee R.J 1 23.4- 4- 52- 9 W 234 39.0

1513 2000 Pak Eng-480/ 8 H Saqlain Mushtaq S 1 74.0-20-164- 8 = 234 39.0

1377 1997 Aus Eng-180/10 A McGrath G.D 1 21.0- 4- 76- 7 * 221 36.8

0428 1956 Eng Aus-205/10 H Laker J.C S 3 51.2-23- 53-10 W 213 35.4

0975 1984 Nzl Eng-463/10 H Cairns B.L 2 45.0-10-143- 7 = 212 35.4

0788 1976 Eng Ind-122/10 A Lever J.K 2 23.0- 6- 46- 7 W 207 34.5

0083 1905 Eng Aus-188/10 H Bosanquet B.J.T S 4 32.4- 2-107- 8 W 197 32.8

1525 2000 Aus Win-109/10 H Gillespie J.N 4 17.0- 5- 40- 6 W 189 31.4

0323 1950 Win Eng-312/10 A Valentine A.L S 1 50.0-14-104- 8 * 185 30.8

1583 2002 Slk Zim-236/10 H Muralitharan M S 1 40.0-19- 51- 9 W 180 30.0

1878 2008 Eng Nzl-123/10 H Anderson J.M 2 21.3- 8- 43- 7 W 165 27.6

0131 1913 Eng Saf-160/10 A Barnes S.F 1 26.5- 9- 56- 8 W 157 26.2

0424 1956 Win Nzl-157/ 9 A Atkinson D.S.t.E S 3 40.0-21- 53- 7 * 145 24.1

0039 1893 Eng Aus-269/10 H Lockwood W.H 2 37.3-11-101- 6 = 133 22.2

This table is ordered by the average of the batting averages of the six

batsmen dismissed. O'Reilly dismissed Walters, Sutcliffe, Wyatt,

Hammond, Hendren and Leyland, two of these on either side of 60.0. An

imposing collection indeed. Gupte accounted for Holt, Hunte, Sobers,

Kanhai, OG Smith and Butcher. Muralitharan dismissed Trescothick,

Strauss, Cook, Pietersen, Collingwood and Flintoff.

One cannot keep these two greats out. Muralitharan and McGrath are the

only bowlers to do this twice in their career. Now for another view of

the same group.

4. Bowling spells in which top six wickets are captured - 2

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R Runs

1525 2000 Aus Win-109/10 H Gillespie J.N 4 17.0- 5- 40- 6 W 14

1726 2004 Aus Pak- 72/10 H McGrath G.D 4 16.0- 8- 24- 8 W 55

0131 1913 Eng Saf-160/10 A Barnes S.F 1 26.5- 9- 56- 8 W 73

0461 1958 Ind Win-222/10 H Gupte S.P S 1 34.3-11-102- 9 * 86

1878 2008 Eng Nzl-123/10 H Anderson J.M 2 21.3- 8- 43- 7 W 86

0788 1976 Eng Ind-122/10 A Lever J.K 2 23.0- 6- 46- 7 W 94

0424 1956 Win Nzl-157/ 9 A Atkinson D.S.t.E S 3 40.0-21- 53- 7 * 95

1804 2006 Slk Eng-190/10 A Muralitharan M S 4 30.0-11- 70- 8 W 106

0323 1950 Win Eng-312/10 A Valentine A.L S 1 50.0-14-104- 8 * 110

0765 1975 Win Aus-169/10 A Roberts A.M.E 3 18.4- 3- 54- 7 W 115

1377 1997 Aus Eng-180/10 A McGrath G.D 1 21.0- 4- 76- 7 * 115

0039 1893 Eng Aus-269/10 H Lockwood W.H 2 37.3-11-101- 6 = 119

1443 1999 Ind Pak-207/10 H Kumble A S 4 26.3- 9- 74-10 W 119

0754 1975 Eng Aus-304/10 A Underwood D.L S 1 38.4- 3-113- 7 * 122

1583 2002 Slk Zim-236/10 H Muralitharan M S 1 40.0-19- 51- 9 W 130

0083 1905 Eng Aus-188/10 H Bosanquet B.J.T S 4 32.4- 2-107- 8 W 137

0990 1984 Eng Win-245/10 H Botham I.T 2 27.4- 6-103- 8 * 142

1029 1985 Nzl Aus-179/10 A Hadlee R.J 1 23.4- 4- 52- 9 W 144

1028 1985 Slk Pak-295/10 A de Mel A.L.F 2 22.0- 1-109- 6 * 156

0428 1956 Eng Aus-205/10 H Laker J.C S 3 51.2-23- 53-10 W 160

0975 1984 Nzl Eng-463/10 H Cairns B.L 2 45.0-10-143- 7 = 239

1110 1988 Aus Win-349/ 9 H Hughes M.G 3 37.0- 9- 87- 8 * 247

1513 2000 Pak Eng-480/ 8 H Saqlain Mushtaq S 1 74.0-20-164- 8 = 288

0913 1981 Aus Pak-500/ 8 H Yardley B S 1 66.0-16-187- 7 * 388

0235 1934 Aus Eng-627/ 9 A O'Reilly W.J S 1 59.0- 9-189- 7 = 404

This table has been ordered by the aggregate of runs scored by the top

six batsmen dismissed by the bowler. This is an indication of the mayhem

which was caused by the bowler.

Gillespie's decimation of the West Indian top order, including Brian

Lara, reads like this: 6, 0, 4, 0, 4, 0. Looks like a telephone number

or a T20 over. See how far ahead Gillespie is of McGrath, whose numbers

are 9, 1, 17, 27, 1, 0. Spare a thought for O'Reilly, who was first in

the previous classification and is now last. The top six English batsmen

scored 52, 63, 0, 4, 132, 153.

Now the bowlers who out-performed their compatriots hundreds of times, okay by more than 12.5 times.

5. Bowling out-performers: many times the rest of the team

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R BAvg TAvg Ratio

1630 2002 Win Bng- 87/10 A Lawson J.J.C 3 6.5- 4- 3- 6 W 0.5 18.2 36.5

1720 2004 Aus Ind-205/10 A Clarke M.J S 3 6.2- 0- 9- 6 * 1.5 48.0 32.0

0290 1947 Aus Ind- 58/10 H Toshack E.R.H 2 3.1- 1- 2- 5 W 0.4 10.8 27.0

0799 1977 Win Pak-180/10 H Croft C.E.H 1 18.5- 7- 29- 8 W 3.6 68.0 18.8

0348 1952 Ind Eng-266/10 H Mankad M.H S 1 38.5-15- 55- 8 W 6.9 100.0 14.5

0527 1962 Win Ind-187/10 H Gibbs L.R S 3 53.3-37- 38- 8 W 4.8 67.5 14.2

1210 1993 Aus Win-146/10 H May T.B.A S 3 6.5- 3- 9- 5 * 1.8 24.6 13.7

0294 1948 Aus Ind-277/10 H Lindwall R.R 3 22.1- 4- 38- 7 W 5.4 72.3 13.3

1899 2008 Aus Saf-281/10 H Johnson M.G 2 24.0- 4- 61- 8 * 7.6 101.5 13.3

0781 1976 Win Eng-435/10 A Holding M.A 2 33.0- 9- 92- 8 W 11.5 151.5 13.2

0047 1896 Eng Saf- 30/10 A Lohmann G.A 4 8.1- 5- 7- 8 W 0.9 11.5 13.1

0823 1978 Win Aus-290/10 H Holder V.A 2 13.0- 4- 28- 6 W 4.7 61.2 13.1

1275 1994 Aus Eng-323/10 H Warne S.K S 4 50.2-22- 71- 8 W 8.9 113.0 12.7

0129 1912 Aus Eng-175/10 A Hazlitt G.R S 3 21.4- 8- 25- 7 * 3.6 45.0 12.6

0743 1974 Eng Pak-226/10 H Underwood D.L S 3 34.5-17- 51- 8 = 6.4 80.0 12.5

Jermaine Lawson's 6 for 3 had an average of 0.5. His fellow bowlers

captured 4 for 73 and the out-performance ratio is a whopping 36.5.

Clarke's equally amazing 6 for 9 had an out-performer ratio of 32.0 and

Ernie Toshack's unbelievable spell of 5 for 2 against India, ended with a

ratio of 27.0. These three are bizarre performances.

Colin Croft's is a genuine case of out-performance. 8 for 29 against 2

for 136, resulting in a ratio of 18.8. Mankad, the peerless Indian

all-rounder captured 8 for 55 against 2 for 200. Shane Warne's 8 for 71

against 2 for 226 is an all-time classic. One would have expected

Muralitharan present in this table. However he appears quite a few times

in earlier tables but not in this one.

Next is an important variation of the top order wicket captures.

6. Based on difference between batting average and runs scored

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R T7W Diff Avg

1906 2009 Win Eng- 51/10 H Taylor J.E 3 9.0- 4- 11- 5 W 5 216 43.3

1756 2005 Aus Eng-155/10 A McGrath G.D 2 18.0- 5- 53- 5 W 5 193 38.6

1971 2010 Pak Eng-446/10 A Mohammad Aamer 1 28.0- 6- 84- 6 * 5 190 38.0

1974 2010 Nzl Ind-266/10 A Martin C.S 3 27.0- 8- 63- 5 = 5 190 38.0

2016 2011 Aus Saf- 96/10 A Watson S.R 2 5.0- 2- 17- 5 * 5 183 36.6

1931 2009 Eng Aus-160/10 H Broad S.C.J 2 12.0- 1- 37- 5 W 5 179 35.8

0652 1969 Nzl Win-417/10 H Motz R.C 1 36.0- 3-113- 5 = 5 177 35.3

1615 2002 Pak Aus-127/10 A Shoaib Akhtar 3 8.0- 2- 21- 5 * 4 181 45.3

0755 1975 Eng Aus-152/10 A Lever P 1 14.4- 2- 38- 6 W 4 175 43.8

1278 1994 Win Ind-114/10 A Benjamin K.C.G 4 17.0- 3- 65- 5 W 4 171 42.8

1104 1988 Pak Aus-165/10 H Iqbal Qasim S 2 39.0-24- 35- 5 W 4 166 41.6

0303 1948 Eng Aus-389/10 H Hollies W.E S 2 56.0-14-131- 5 * 4 165 41.3

0255 1936 Eng Aus- 58/10 A Allen G.O.B 4 8.0- 0- 36- 5 W 4 164 41.0

1823 2006 Ind Saf- 84/10 A Sreesanth S 2 10.0- 3- 40- 5 W 4 163 40.7

This is based on the dismissals of top-7 batsmen. The bowlers who

captured at least 4 wickets are considered. For each such bowler, I have

compiled the sum of the difference between the batting average and the

runs scored by the batsman. This has been averaged and we get the

notional runs saved. This table lists the bowlers whose average runs

saved value is greater than 35/40 depending on whether the bowler

captured 5/4 wickets.

Jerome Taylor's once-in-a-lifetime effort of 5 for 15 is on top. He

dismissed Strauss (9), Cook (0), Pietersen (1), Collingwood (1) and

Prior (0). The total batting average of these five batsmen was 227.5 and

the saved runs average worked out to 43.3.

McGrath captured the wickets of Trescothick (4), Strauss (2), Vaughan

(3), Bell (6) and Flintoff (0). The total of batting averages for these

five comes to 208, leading to a runs saved value of 38.6. Shoaib Akhtar

dismissed Ponting (7), M.Waugh( (0), S.Waugh (0) and Gilchrist (5). The

total batting average was 192.5, leading to a runs saved value of 45.3.

Shoaib Akhtar's and McGrath's performances were also away.

Martin's was during the 15 for 5 debacle of India and Watson's was on that manic November Thursday at Newlands.

Let us now look at bowling performances in bat-fests. The match RpW value here applies to the top-7 batsmen only.

7. Bowling performances in matches with high RpW values: > 50.0

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R MatRpW

0781 1976 Win Eng-435/10 A Holding M.A 2 33.0- 9- 92- 8 W 50.2

1680 2004 Ind Aus-474/10 A Kumble A S 2 46.5- 7-141- 8 = 60.2

0416 1955 Ind Nzl-326/10 H Gupte S.P S 2 76.4-35-128- 7 = 54.5

0564 1964 Aus Eng-611/10 A McKenzie G.D 2 60.0-15-153- 7 = 66.9

0235 1934 Aus Eng-627/ 9 A O'Reilly W.J S 1 59.0- 9-189- 7 = 54.5

1981 2010 Aus Eng-260/10 H Siddle P.M S 1 16.0- 3- 54- 6 = 52.5

0781 1976 Win Eng-203/10 A Holding M.A 4 20.4- 6- 57- 6 W 50.2

0404 1955 Aus Win-382/10 A Lindwall R.R 1 24.5- 3- 95- 6 = 52.3

1981 2010 Eng Aus-481/10 A Finn S.T 2 33.4- 1-125- 6 = 52.5

1831 2007 Eng Win-437/10 H Panesar M.S S 2 36.1- 3-129- 6 = 50.5

1810 2006 Slk Saf-434/10 H Muralitharan M S 3 64.0-11-131- 6 W 52.3

1912 2009 Pak Slk-606/10 H Umar Gul 1 37.0- 2-135- 6 = 59.7

0450 1958 Win Pak-328/10 H Atkinson E.S.t.E 1 21.0- 7- 42- 5 W 56.2

0274 1939 Win Eng-352/10 A Constantine L.N 1 23.1- 2- 75- 5 = 50.7

1681 2004 Saf Win-427/10 H Nel A 2 28.1- 8- 87- 5 = 53.2

1816 2006 Win Pak-357/10 A Taylor J.E 1 26.0- 6- 91- 5 = 50.3

1303 1995 Win Eng-454/10 A Ambrose C.E.L 1 42.0-10- 96- 5 = 59.5

1034 1986 Ind Aus-396/10 A Yadav N.S S 2 62.3-21- 99- 5 = 53.1

0271 1939 Eng Saf-530/10 A Perks R.T.D 1 54.4- 5-100- 5 = 56.6

1891 2008 Ind Aus-577/10 H Sehwag V S 2 40.0- 9-104- 5 = 52.9

1148 1990 Eng Ind-454/10 H Fraser A.R.C 2 39.1- 9-104- 5 W 51.7

1614 2002 Ind Eng-515/10 A Harbhajan Singh S 1 38.4- 6-115- 5 = 51.7

0744 1974 Pak Eng-545/10 A Intikhab Alam S 2 51.4-14-116- 5 = 53.9

1850 2007 Ind Pak-456/10 H Harbhajan Singh S 2 45.5- 9-122- 5 = 54.4

1911 2009 Eng Win-749/ 9 A Swann G.P 2 50.4- 8-165- 5 = 81.4

These are heart-breakers. However most of these performances have been

in drawn matches, as the qualification criteria suggests. The stand-out

performance is Michael Holding's 8 for 92 and 6 for 57 on an Oval

shirt-front pitch, possibly the greatest match bowling performance ever.

He, almost certainly more than Viv Richards, was responsible for the

fine West Indian win. Harbhajan Singh has held his own on the flat

wickets twice, the only bowler to do so, other than Holding. Virender

Sehwag is an unlikely name in this table.

Now for a unique table. I would not spoil the fun. Pl see the table.

8. They captured 5 and only 5 wickets: but nos 7 to 11

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R

1508 2000 Eng Win- 61/10 H Caddick A.R 3 11.2- 5- 14- 5 W

1432 1998 Pak Zim-183/10 H Saqlain Mushtaq S 1 13.5- 3- 32- 5 =

1431 1998 Aus Eng-191/10 H Gillespie J.N 3 15.2- 2- 88- 5 W

0949 1983 Win Ind-174/10 H Roberts A.M.E 3 24.3- 9- 39- 5 W

0608 1966 Win Eng-240/10 A Sobers G.St.A 2 19.3- 4- 41- 5 W

Other fifers

1755 2005 Slk Win-113/10 H Muralitharan M S 3 21.0- 8- 36- 6 W

1504 2000 Slk Saf-269/10 H Muralitharan M S 3 35.0- 5- 84- 7 W

1423 1998 Slk Eng-445/10 A Muralitharan M S 1 59.3-14-155- 7 W

1175 1991 Eng Win-176/10 H Tufnell P.C.R S 2 14.3- 3- 25- 6 W

1058 1986 Pak Win-211/10 H Imran Khan 3 22.3- 2- 46- 6 =

1040 1986 Nzl Aus-103/10 H Bracewell J.G S 3 22.0- 8- 32- 6 W

0986 1984 Aus Win-509/10 A Hogg R.M 2 32.4- 4- 77- 6 *

0947 1983 Ind Pak-323/10 A Kapil Dev N 1 30.5- 7- 85- 8 =

0877 1980 Win Nzl-305/10 A Garner J 2 36.2-15- 56- 6 =

0725 1973 Win Eng-255/10 A Boyce K.D 4 21.1- 4- 77- 6 W

0703 1972 Ind Eng-200/10 H Chandrasekhar B. S 2 41.5-18- 79- 8 *

0463 1959 Win Ind-154/10 A Gilchrist R 3 21.0- 7- 55- 6 W

0436 1957 Saf Eng-254/10 H Tayfield H.J S 3 50.3-14- 69- 8 =

0250 1936 Aus Saf- 98/10 A Grimmett C.V S 3 19.5- 9- 40- 7 W

0075 1902 Saf Aus-296/10 H Llewellyn C.B 2 22.0- 3- 92- 6 =

These bowlers captured fifers, no doubt. But they also captured the LAST

five wickets. And, to boot, these were the ONLY 5 wickets captured by

the first five them. Don't think it is easy to do that. Some other

bowler could spoil the fun. One batsman could remain not out. Everything

has to work. This leaves us with just 5 bowlers, almost all of recent

vintage. It is ironic that Gillespie appears at the top of the top-6

wickets list and also here.

If I did not have the ONLY 5 wickets criteria, there are quite a few, 20

in all, who fit in. However these other 13 bowlers have had the

satisfaction of capturing one or more top order wickets. Muralitharan

appears thrice here indicating the way he dominated the late order

batting.

Now for those who toiled for hours on end. These are fifers in innings of 600+ runs.

9. Bowling on and on and on ... in 600+ innings

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R

0193 1930 Win Eng-849/10 H Scott O.C S 1 80.2-13-266- 5 =

0198 1930 Eng Aus-695/10 H Peebles I.A.R S 2 71.0- 8-204- 6 *

0740 1974 Ind Eng-629/10 A Bedi B.S S 1 64.2- 8-226- 6 *

0564 1964 Aus Eng-611/10 A McKenzie G.D 2 60.0-15-153- 7 =

0235 1934 Aus Eng-627/ 9 A O'Reilly W.J S 1 59.0- 9-189- 7 =

0279 1946 Eng Aus-645/10 A Wright D.V.P S 1 58.2- 4-167- 5 *

1911 2009 Eng Win-749/ 9 A Swann G.P 2 50.4- 8-165- 5 =

0970 1983 Aus Pak-624/10 H Lillee D.K 2 50.2- 8-171- 6 =

0851 1979 Ind Eng-633/ 5 A Kapil Dev N 1 48.0-15-146- 5 *

1079 1987 Eng Pak-708/10 H Dilley G.R 1 47.3-10-154- 6 =

0645 1969 Aus Win-616/10 H Connolly A.N 3 45.2- 7-122- 5 =

1852 2007 Pak Ind-626/10 A Yasir Arafat 1 39.0- 5-161- 5 =

0945 1983 Ind Pak-652/10 A Kapil Dev N 2 38.4- 3-220- 7 *

0259 1937 Eng Aus-604/10 A Farnes K 1 38.1- 5- 96- 6 *

1912 2009 Pak Slk-606/10 H Umar Gul 1 37.0- 2-135- 6 =

1935 2009 Slk Ind-642/10 A Herath HMRKB S 1 33.0- 2-121- 5 *

0989 1984 Eng Win-606/10 H Pringle D.R 2 31.0- 5-108- 5 *

0304 1948 Ind Win-631/10 H Rangachari C.R 1 29.4- 4-107- 5 =

This table is ordered by balls bowled. Scott bowled a third of the team

overs. Lucky he got a couple of wickets in the end. Peculiar match. A

timeless Test, which was drawn, by agreement. West Indies fall behind by

577 runs and England bat again. Then Headley's famous 223 saves the

match. 9 days, and no result. A follow-on and they might very well have

won by an innings. I know Shri might have something to say: but strange

captaincy by Hon.FSG Calthorpe, the lone "gentleman" in the team. Over 9

days, he scored 13, bowled 4 overs and batted when he should have

bowled.

Commendable are McKenzie and Kapil Dev who captured 7 wickets amongst

the batting mayhem although Kapil went for nearly 6 runs per over,

thanks to four Pakistani centuries. Also noteworthy is Farnes' capturing

6 for 96 out of a 600+ total.

Now for some nice alternate tables. First is the one where the bowlers have been very economical.

10. 5-wkt bowling performances with RpO less than 1.0

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R RpO

0527 1962 Win Ind-187/10 H Gibbs L.R S 3 53.3-37- 38- 8 W 0.71

0212 1931 Aus Saf-170/10 H Ironmonger H 2 47.0-29- 42- 5 W 0.89

0413 1955 Pak Nzl-124/10 H Zulfiqar Ahmed S 3 46.3-21- 42- 6 W 0.90

0479 1959 Aus Pak-134/10 A Mackay K.D 3 45.0-27- 42- 6 W 0.93

1104 1988 Pak Aus-165/10 H Iqbal Qasim S 2 39.0-24- 35- 5 W 0.90

0413 1955 Pak Nzl-164/10 H Zulfiqar Ahmed S 1 37.2-19- 37- 5 W 0.99

0785 1976 Ind Nzl-141/10 H Bedi B.S S 4 33.0-18- 27- 5 W 0.82

1113 1989 Win Aus-401/10 A Marshall M.D 2 31.0-16- 29- 5 * 0.94

0025 1887 Eng Aus- 97/10 A Barnes W 4 30.4-29- 28- 6 W 0.91

1394 1998 Slk Zim-140/10 H Muralitharan M S 2 29.0-18- 23- 5 W 0.79

0277 1946 Eng Ind-170/10 H Pollard R 2 27.0-16- 24- 5 = 0.89

0593 1965 Eng Nzl-166/10 H Titmus F.J S 3 26.0-17- 19- 5 W 0.73

0456 1958 Eng Nzl- 67/10 H Laker J.C S 1 22.0-11- 17- 5 W 0.77

0707 1973 Aus Pak-106/10 H Walker M.H.N 4 21.2- 8- 15- 6 W 0.70

0250 1936 Aus Saf-157/10 A O'Reilly W.J S 1 21.0-11- 20- 5 W 0.95

0434 1956 Eng Saf- 72/10 A Bailey T.E 4 20.4- 6- 20- 5 W 0.97

0009 1882 Eng Aus- 63/10 H Barlow R.G 1 20.4-22- 19- 5 * 0.92

1516 2000 Aus Win- 82/10 H McGrath G.D 1 20.0-12- 17- 6 W 0.85

0381 1954 Saf Nzl- 79/10 H Tayfield H.J S 2 18.4- 7- 13- 6 W 0.70

1156 1990 Ind Slk- 82/10 H Raju S.L.V S 2 17.5-13- 12- 6 W 0.67

0681 1971 Eng Nzl- 65/10 A Underwood D.L S 1 15.4- 7- 12- 6 W 0.77

0212 1931 Aus Saf-117/10 H Wall T.W 3 15.1- 7- 14- 5 W 0.92

0906 1981 Eng Aus-121/10 H Botham I.T 4 14.0- 9- 11- 5 W 0.79

1687 2004 Eng Win- 47/10 A Harmison S.J 3 12.3- 8- 12- 7 W 0.96

0047 1896 Eng Saf- 30/10 A Lohmann G.A 4 8.1- 5- 7- 8 W 0.86

0216 1932 Aus Saf- 36/10 H Ironmonger H 1 7.2- 5- 6- 5 W 0.82

1630 2002 Win Bng- 87/10 A Lawson J.J.C 3 6.5- 4- 3- 6 W 0.44

0290 1947 Aus Ind- 58/10 H Toshack E.R.H 2 3.1- 1- 2- 5 W 0.63

These are matches in which the number of overs bowled are greater than

the number of runs conceded. This is ordered by the number of overs

bowled. The table is led by Gibbs who had a RpO value of 0.71 while

bowling 53 overs and capturing 8 wickets. Is it is possible today ?

Look at Marshall's performance, the stand-out one amongst this lot. Out

of an Australian total of 401, he captures 5 for 29, at an RpO of 0.94,

while his compatriots capture 5 for 338, at an RpO figure of 2.1. In

fact he just misses out on the out-performer table, with a ratio of

11.7. Lohmann's 8 for 7 has appeared in various tables. Only point of

question would be the dicey quality of South African batting and the

minefields he bowled on.

Now for the final table in this first part article. The two extreme sets of fifers.

11. The two extremes of 5-wkt bowling performances

MtId Year For Vs Score HA Bowler BT I <--Analysis--> R

0193 1930 Win Eng-849/10 H Scott O.C S 1 80.2-13-266- 5 =

0371 1953 Ind Win-576/10 A Mankad M.H S 2 82.0-17-228- 5 =

0740 1974 Ind Eng-629/10 A Bedi B.S S 1 64.2- 8-226- 6 *

0945 1983 Ind Pak-652/10 A Kapil Dev N 2 38.4- 3-220- 7 *

1892 2008 Aus Ind-441/10 A Krejza J.J 1 43.5- 1-215- 8 *

1336 1996 Zim Pak-553/10 A Strang P.A S 2 69.0-12-212- 5 =

0198 1930 Eng Aus-695/10 H Peebles I.A.R S 2 71.0- 8-204- 6 *

0503 1961 Pak Ind-539/ 9 A Haseeb Ahsan S 2 84.0-19-202- 6 =

...

...

...

1720 2004 Aus Ind-205/10 A Clarke M.J S 3 6.2- 0- 9- 6 *

1210 1993 Aus Win-146/10 H May T.B.A S 3 6.5- 3- 9- 5 *

0047 1896 Eng Saf- 30/10 A Lohmann G.A 4 8.1- 5- 7- 8 W

0153 1924 Eng Saf- 30/10 H Gilligan A.E.R 2 6.3- 4- 7- 6 W

0216 1932 Aus Saf- 36/10 H Ironmonger H 1 7.2- 5- 6- 5 W

1630 2002 Win Bng- 87/10 A Lawson J.J.C 3 6.5- 4- 3- 6 W

0290 1947 Aus Ind- 58/10 H Toshack E.R.H 2 3.1- 1- 2- 5 W

This is the one table which contains the two ends of the bowling

spectrum. Fifers for 200 runs and above and fifers for 10 runs and

below. Most of these bowlers have already appeared in the earlier tables

and this is just a different classification. Spare a thought for poor

Krejza. On debut he toils hard with a 8-for-million performance and then

is forgotten.

Barring table 8, which points to a slightly negative aspect of bowlers,

in which Muralitharan appears three times, he has appeared 10 times in

the other 11 tables. This may not be conclusive but is a pointer to the

range and depth of his bowling achievements. Lohmann, no surprise,

appears 8 times. Signs of the times he bowled in. Two bowlers,

contrasting in their teams' strengths, McGrath and Kapil, appear 7 times

each. Wasim and Waqar appear very few times. That is a sign of the way

they shared the spoils.